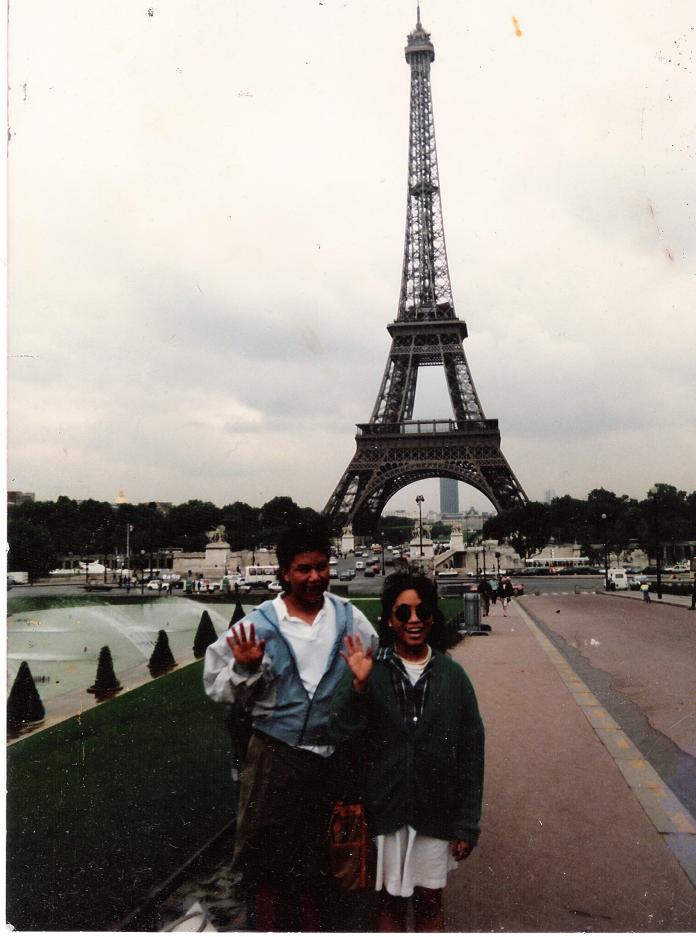

The summer before I went to law school, my parents announced that the whole family was taking a ten-day trip to Paris and London, one of those last great family trips before the kids leave home for good. It was a fun and memorable trip, especially from a culinary standpoint – I’d never been to Paris, and the first day, in an attempt to stay awake in the afternoon, I went for a walk in our Quartier Latin neighborhood, where we were staying not too far from Notre Dame. There I passed tiny Syrian shops displaying great trays of multicolored olives, herby vegetable salads, fattoush, and dozens of varieties of phyllo pastries, Tunisian briq stands, couscouseries – the first time I had encountered most of those foods, at least in that form. I had just taken up cooking that year, if in a totally amateurish way that mostly involved wrapping everything in Pepperidge Farms puff pastry and trying not to burn down the kitchen. Back then, the only olives you reliably could get in Milwaukee were green pimento-stuffed cocktail olives and maybe the occasional kalamata in a jar; couscous came in boxes from Near East Foods, complete with flavor packets of highly un-Moroccan herbed chicken bouillon, or dehydrated broccoli and cheese. No one was topping pizzas with fried eggs, or serving perfect little scoops of fruit flavored gelato outside the park in summer, much less selling giant ropes of blood sausage, made according to the family’s 300 year old recipe.

My dad had a friend in Paris, a businessman who had lived in the city for many years, and in the days to come, he showed us around the city and took us out to eat. One night, we drove to the western side of the city, to the notorious Bois de Boulogne, and boarded a small boat to a little island in the Lac Interieur for dinner at the Chalet des Iles; the next night, we went to the Tour d’Argent, which at the time still had all three Michelin stars.

Tour d’Argent was my first experience with that kind of fine dining. I had no idea what to order – growing up as a picky kid in the suburbs provided no training for this moment – so I surveyed the menu first for the familiar. Duck- ok, I knew liked duck, and that happened to be a house specialty, so I ordered duck as a main course. But I was at a loss when it came to the rest of the menu – it seemed lame to come all the way to Paris to a three-star restaurant and try to order, say, salmon or chicken. I decided to go with plan B: things I’d heard about but never tried. Soon after that, a man’s arm appeared on my right side and slid a ballotine of foie gras before me. Later, the same arm arrived with a plate of ris de veau, veal sweetbreads, in a creamy sauce with vol-au-vent. By the time I tasted the duck, I knew two things: one, I wasn’t a picky eater anymore, and two, I was going to learn to cook for real.

The trip kind of went off the rails a few days after that – my brother ate an undercooked poulet rôti at the Musée d’Orsay cafeteria on our last full day in Paris and spent the London segment of the trip racked with salmonella, which he unfairly blamed on the copious quantities of lamb couscous from the Quartier Latin couscouserie the night before. I ran into some University of Wisconsin students I knew at our hotel’s outdoor bar, got super drunk with them on cheap wine, and knocked over a huge lamp on my 3 am crawl up five flights of stairs to the hotel room just hours before leaving for London (Mom, if you’re reading this, that’s what happened. Now you know). Last day shenanigans aside, though, we had a great time. And we had sweetbreads.

Sweetbreads are the thymus and/or pancreas of the veal or lamb. The thymus, or neck sweetbread, is long and cylindrical – unlike the somewhat more globular pancreas – and is absent in the adult animal. Probably because few people enjoy preparing them at home, sweetbreads are not widely available in stores, but if you have access to a true butcher or a good meat market, you should be able to order them. For the best flavor, and to make them easier to handle, you need to prepare sweetbreads thoroughly, which involves some planning – they should be soaked in salt water to remove blood, the membrane needs to be removed, and then they should be dried thoroughly and compressed somewhat to form them and make them easier to handle. Rich and mild, they’re versatile – you can roast them whole (one of my favorite ways), slice and deep fry, or poach in courtbouillon and sauce. They need acid to balance the fat and the slight visceral quality. Don’t overcook sweeties – you don’t want them to become rubbery and tough. Short of that – well, I think they need to be cooked through until just completely cooked but still creamy. I’ve had sweetbreads cooked what can only be described as medium rare – warm but not completely cooked through to the interior – and although I respect the decision to serve them in a more natural form (this was at Manresa), I found the sweetbreads really organ-y, and not in a good way.

A last note about sweetbreads: probably not an everyday food. 100g (3 1/2 ounces) of sweetbreads ring in at 236 calories, 77% of them from fat (!). Of course, they’re incredibly rich, so you probably won’t eat more than 50g at a shot in a tasting portion, and it’s not going to kill you if you don’t do it every day.

Pan-roasted sweetbreads, cauliflower, sherry vinegar reduction

You don’t think of cauliflower as a Spanish vegetable, but Spain grows much of the European Union’s cauliflower (second only to Italy) and, in Spain, cauliflower often is served with a pimentón and garlic sauce. Here, whole sweetbread lobes are dusted in pimentón, roasted and served atop sweet roasted cauliflower with a butter-enriched sherry vinegar reduction.

I garnished the plate with a powder of ground dried arbequina olives. The earthiness and slight bitterness of the olives perfectly offsets the rich sweetbread and the sweet/sour sauce; if you don’t want to deal with dehydration, just pit and halve some arbequinas or niçoise olives and sprinkle them around the plate.

2 veal sweetbreads

1 tsp each Pimentón de la vera agridulce (bittersweet) and picante (hot)

salt and piment d’espelette

1/2 c Wondra

1 head cauliflower, florets only

1 large leek, white and light green only, julienned

vegetable oil

olive oil, preferably Spanish

1/4 c dry white wine

1/4 c sherry vinegar

3 tbsp cold unsalted butter, divided

1/4 c pine nuts

2 dozen arbequina olives, pitted and halved

thyme leaves, washed and dried

parsley leaves, washed and dried

Prepare the sweetbreads at least 8 hours and up to a day in advance by soaking in cold water (in the refrigerator), changing twice if you can. The water should be salted 1 tsp per 2 cups.

Drain. Remove the membrane with a thin, sharp knife and then divide into large lobes (along natural lines). Roll the sweetbread lobes in clean cheesecloth or kitchen towel to form and dry. Refrigerate until ready to use.

Convection oven 200F/93C.

Place the olives in a single layer on a silpat-lined sheet pan. Bake until dry (about 90 minutes; they don’t have to be rock-hard, just not moist). Remove from the oven and cool. Transfer to a clean spice grinder and grind to a powder. Cover tightly until use.

Oven 400F/205C.

Place a small saucepot over medium heat with about 2 tbsp olive oil. When hot, add the leeks. Cook slowly until golden brown. Remove with a slotted spoon; season and set aside.

Place a small saucepot over medium low heat with the dry white wine. Reduce to au sec (until syrupy and nearly totally cooked off); add the vinegar. Reduce again by 2/3. At this point you can hold until service (stop just short of the 2/3 reduction).

Place the pine nuts in a single layer on a sheet pan; toast in the oven until uniformly golden. Remove and cool.

Trim the cauliflower florets to remove the stalks entirely, leaving only 1/2″ or slightly smaller chunks of floret. Reserve the trimmings for another use, such as soup. Toss the cauliflower lightly in oil in a roasting pan and place in the oven. Roast until golden brown; toss and return to the oven and continue to roast. At this time, turn the oven down to 300F/150C.

Combine the pimentón and about 1/2 tsp salt and a big pinch of espelette. Dust the sweetbreads with this mixture. Place a large skillet over medium heat and, when hot, add 1 tbsp each vegetable oil and butter. Dredge the sweetbreads quickly in Wondra and shake off all excess. They should be just barely dusted. Fry on one side until golden; turn over and place in the 300F oven. Roast until just cooked through and still creamy; remove the cauliflower if necessary to prevent overcooking.

Bring the vinegar reduction back to a simmer and continue to reduce to 2/3 if you were holding it previously. Remove from heat and whisk in the cold butter off heat, swirling to incorporate.

Serve the sweetbreads atop the cauliflower and leek, garnished with the fresh herbs, pine nuts, olive powder, and the vinegar reduction.

Sweetbreads with bacon and pickled onion

I hate the “everything’s better with bacon” bandwagon – it’s so cliché; everything is NOT better with bacon, and bacon has become the universal crutch for adding a tasty component to a dish that otherwise lacks interest. Having said that, sweetbreads are a natural and classic pairing with bacon.

This was a hasty dish conceived to use one leftover sweetbread (prepared but not cooked for the above recipe) and the end chunk of some house-made bacon on a weeknight. Assuming that you thought about making sweetbreads in advance (and you would have to, since it’s almost impossible to just pick these up at the butcher on the way home), and you began soaking them the night before after dinner, this dish can come together in about half an hour. Just trim up the sweetbreads while cooking up the bacon and onions, and then give it a pan roasting – all in the same pan.

2 veal sweetbreads

salt and piment d’espelette

1/2 c Wondra

4 oz (1/4 lb) slab bacon, cut into 1/4″ x 1″ batons

one small red onion, peeled and 1/2″ dice

3 tbsp red wine vinegar, divided

dijon mustard

chives, washed and dried

thyme leaves, washed and dried

parsley leaves, washed and dried

Prepare the sweetbreads at least 8 hours and up to a day in advance by soaking in cold water (in the refrigerator), changing twice if you can. The water should be salted 1 tsp per 2 cups.

Drain. Remove the membrane with a thin, sharp knife and then divide into large lobes (along natural lines). Roll the sweetbread lobes in clean cheesecloth or kitchen towel to form and dry. Refrigerate until ready to use.

Oven 300F/150C.

Place a skillet over medium heat and, when hot, add the bacon batons. Reduce the heat slightly. Cook slowly until brown and crisp. Remove with a slotted spoon; season and set aside. Remove all but 1 tbsp of the bacon fat from the pan and reserve.

Return the pan with the 1 tbsp bacon fat to medium heat and, when hot, add the onion. Reduce heat slightly and sauté slowly until golden. Add the red wine vinegar and cook, stirring, until vinegar has been absorbed or evaporated. Season with salt and combine with the bacon. Wipe out the pan with paper towels.

Combine the salt and espelette. Season the sweetbreads lightly with this mixture. Place a large skillet over medium heat and, when hot, add 2 tbsp of the remaining bacon fat (if necessary, supplement with vegetable oil). Dredge the sweetbreads quickly in Wondra and shake off all excess. They should be just barely dusted. Fry on one side until golden; turn over and place in the oven. Roast until just cooked through and still creamy.

Remove from the pan and return the bacon and onions to the pan over medium heat, tossing just to moisten and warm through.

If you have any bacon fat remaining, make a quick vinaigrette by whisking together 1 tsp mustard, a pinch of salt, and 1 tbsp red wine vinegar, and then whisking in 3 tbsp bacon fat (make up the rest with a neutral oil like grapeseed if you don’t have enough). Whisk in some snipped chives and thyme leaves.

Serve the sweetbreads atop the bacon and pickled onion, garnished with the fresh herbs and, if you have it, the vinaigrette.

Wendy sweetbreads are the thymus gland NOT the pancreas. The thymus gland consists of two parts the throat sweetbread (thin and knobbly) and the heart sweetbread (heart refers to shape not location) which is rounder and more compact. The pancreas is a gland found near the stomach and too often confused with sweetbreads.

I found it interesting that you didn’t poach your sweetbreads before cooking. I always poach and press them first.

As I am from another planet – just what is Wondra – a type of flour?

Hi Jennifer – your comment about the pancreas is interesting and I wonder whether this isn’t one of those differences between British and American meat fabrication (on the US side, things tend to be far more fast and loose, both in terms of butchery and terminology, I find). I do note that Larousse describes sweetbreads as thymus and/or pancreas, as do the Oxford Companion to Food and the Food Lover’s Companion. Perhaps I could do some fieldwork amongst butchers to see for myself!

Regarding Wondra – probably not available under that name in the UK, but it’s a low-protein, pregelatinized wheat flour that dissolves readily and has slightly grainy but very fine texture. It doesn’t clump and if you do make flour-thickened sauces (I rarely do, but it does happen at holidays), Wondra is the best. I would look for “instant blending flour” or “instant flour.”

And finally, about the sweetbread poaching. I do poach sometimes, but not usually. It takes additional time and I usually have soaked in a light brine for up to two days first with a few changes of water, so the organ-y taste is pretty much gone. But poaching yields a firmer texture and sometimes I like that, and it does make the membrane much easier to remove, which is a plus, so maybe next time I cook sweeties I’ll poach them first. I think I mentioned once that I had a sweetbread with a super organ-y taste that was not cooked through; that one really should’ve been poached.

You do know I am in Canada most of the time Wendy?

I hate to challenge Alan Davidson but he is wrong. And what edition of Larousse do you have? Mine, the classic translation 1961, defines sweetbreads as the thymus gland of calf and lamb. Julia Child in Mastering the Art of French Cooking back me up too. You can eat pancreas but please don’t call it a sweetbread. As you can see I am on a mission here. I think it will continue when my next book Odd Bits is published in September.

I don’t know where I got it in my head that you were in the UK! Sorry about that.

It’s in the 2001 US edition of Larousse – “The culinary term for the thymus gland (in the throat) and the pancreas (near the stomach) in calves, lambs and pigs, although the latter are not much used. Thymus sweetbreads are elongated and irregular in shape; pancreas sweetbreads are larger and rounded.” And Jacques Pepin’s Techniques also describes both the thymus and pancreas: “Sweetbreads are glands. The elongated sweetbread, the thymus, is at its best in young calves and almost disappears in older animals. The round sweetbread, the pancreas, is considered the better of the two. In old animals, it becomes mushy and pasty, but is still used by some cooks in stew.” Joy of Cooking (1981 ed. and again in 2006) says the same – “Sweetbreads, properly so-called, are the rounded, more desirable “heart” or “kernel” types, the pancreas. The thinner “throat” type is the thymus.”

Despite all the authority on the subject in this direction, I will concede that I am not authoritative on the use of pancreas vs thymus as sweetbreads. So I’m interested to hear from you about this – if pancreas isn’t properly categorized as sweetbreads, how did the error come about and become so widespread? I think that’s as interesting as whether it is or isn’t.

I don’t like the US edition of Larousse too Americanized. Will check the original French sweetbreads entry. Mine is an the original English translation so no mention of the pancreas. Would like to find an early Joy of Cooking too. I dusted of my Jacques Pepin Techniques that I have in French and you’re right. He is the only Frenchman I know who calls the pancreas a sweetbread.

You’re absolutely right Wendy the origin of the confusion is the interesting question. It’s my next project. Please send me anything you come across. Can you do it directly or via Facebook.

Thanks for this conversation.