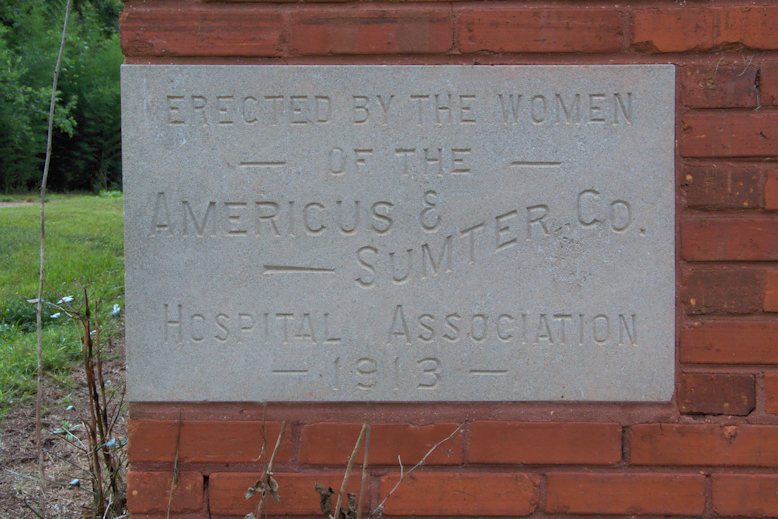

The first facility in South Georgia where black doctors, nurses, and pharmacists could train, practice, and serve people of color, the Americus Colored Hospital was established by Dr. William Stuart Prather (1868-1941), a white physician who was well aware of the health care needs of this under-served community. He bought the property and built this state-of-the-art facility, with the cooperation and contributions of the Americus Negro Business League and the Americus Junior Welfare League.

According to the Americus-Sumter County Movement Remembered Committee (ASMRC), 33 doctors, 2 dentists, 2 pharmacists, 6 registered nurses, and 18 nursing professionals were associated with the hospital. The resulting black middle class that grew out of this experiment was one of the most vibrant in the state; in fact, Americus-Sumter County had more black professionals and landowners than anywhere else in Georgia from the 1920s-1942.

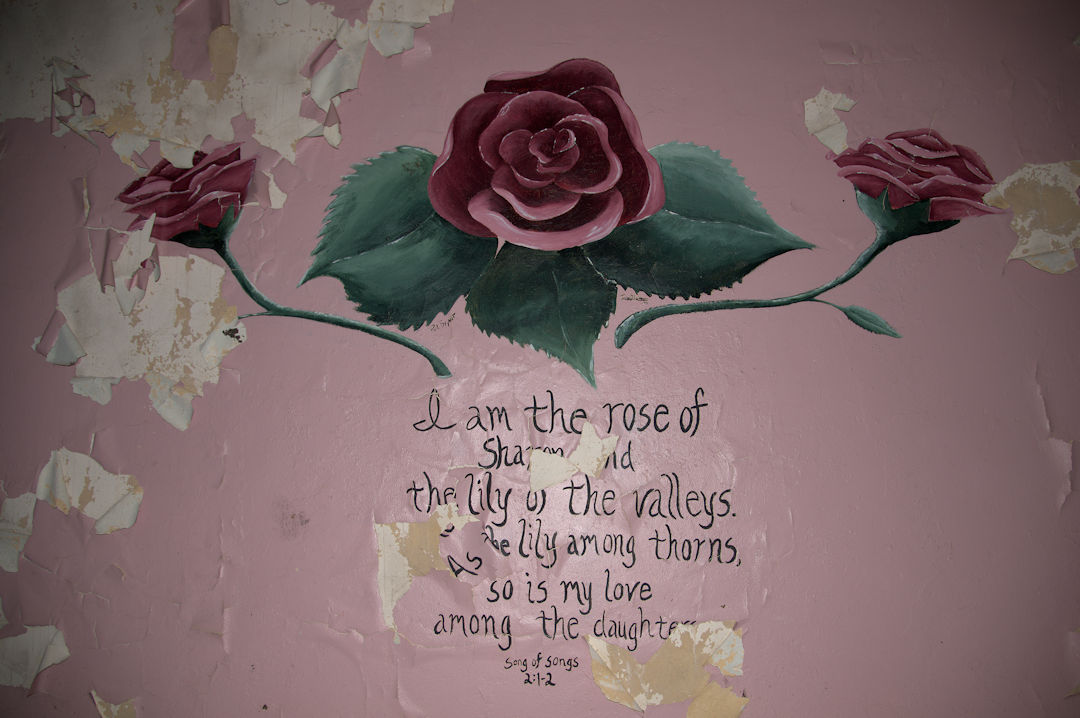

Though it faced numerous difficulties, it was an important resource for the African-American community until it closed in 1953. At that time, Sumter Regional Hospital opened its doors, and because it used federal funds via the Hill-Burton Act, couldn’t discriminate by race. The act didn’t mandate desegregation, however, and Sumter Regional was racially compartmentalized. Since no black doctors were hired, much of the black middle class left Americus, resulting in a negative economic impact. The Americus Chapter of the City Federation of Colored Women’s Clubs, purchased the Colored Hospital building and used it as a nursery and youth center. During the Civil Rights Movement, it also served as a Freedom School and Training Center.

Presently, it is being restored for use as the Americus Civil Rights and Cultural Center.