Attila The Hun

Scourge of God

The short-lived ascension and dominance of the Huns was driven by the leadership of Attila, whose name means “Little Father.”

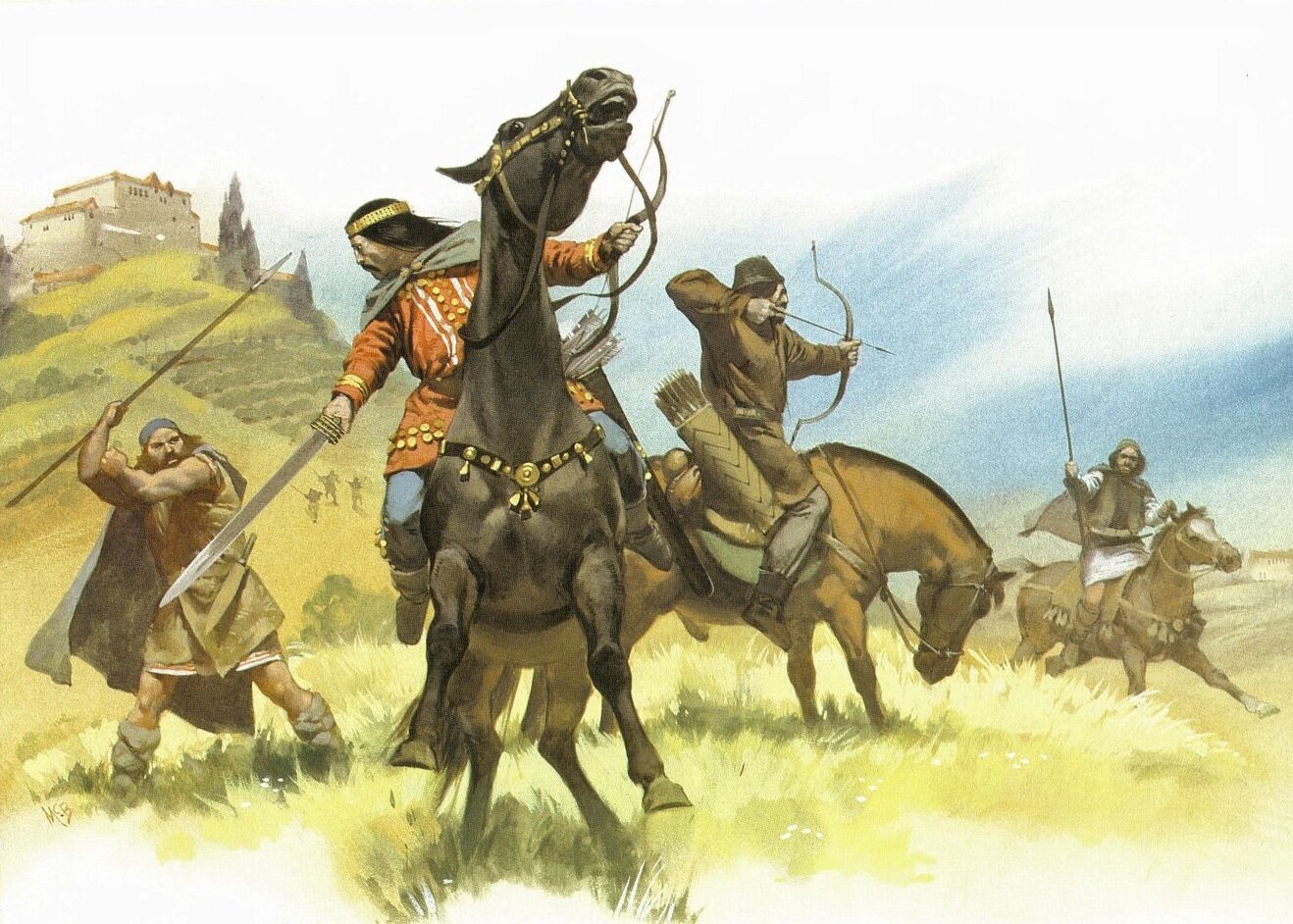

Sarah Pruitt, writing for History.com, dispels some common misperceptions about Attila, which I admit to having had myself. Far from the stereotype of the unwashed, uneducated barbarian, Attila was born into the most powerful family north of the Danube River. His uncles, Octar and Ruga, jointly ruled the Hun Empire in the late 420s and early 430s. Attila and his elder brother, Bleda, received instruction in archery, sword fighting, and how to ride and care for horses. They also spoke–and perhaps read–both Gothic and Latin, learned military and diplomatic tactics, and were likely present when their uncles received Roman ambassadors.

After the death of their uncle Ruga who was campaigning against Constantinople in 433 CE, both Attila and Bleda ruled jointly. Each brother had control of their own regions, populace, and armies.

According to Joshua Mark in an article for worldhistory.org: Attila and Bleda together brokered the Treaty of Margus with Rome in 439 CE. This treaty continued the precedent of Rome paying off the Huns in return for peace, which would, more or less, remain a constant stipulation in Roman-Hun relations until Attila's death.

The annual payment of 700 pounds of gold, or about $19M in today’s dollars, bought the promise not to attack Roman towns. With a tenuous treaty in place, Roman legions guarding the border were pulled to fight in Sicily against the Vandals. With unguarded territory before them, Attila and his brother saw an opportunity to return to their raiding ways. They invented outrage and declared the treaty invalid.

The historian Michael Lee Lanning writes: Attila and his brother valued agreements little and peace even less. Over the next ten years, the Huns invaded territory which today encompasses Hungary, Greece, Spain, and Italy. Attila sent captured riches back to his homeland and drafted soldiers into his own army while often burning the overrun towns and killing their civilian occupants. Warfare proved lucrative for the Huns but wealth apparently was not their only objective. Attila and his army seemed genuinely to enjoy warfare, the rigors and rewards of military life were more appealing to them than farming or attending livestock.

In 441 CE, they launched their Danube campaign, as it will be known, as a full-scale invasion that ravaged cities and towns in the trading province of Illyricum. Despite the fact the legions were not there, these cities were well fortified and well defended. But times had changed.

Christopher Kelly in “The End of Empire” details the Huns’ new approach to fortified defenses that surrounded many of these towns. “Part of the success of Attila’s Danube campaign lay in his army’s skill at siege warfare. Seventy years earlier, the inability to take Roman strongholds, and seize the treasure and grain stored there, had hampered the Goth’s offensive. Attila ensured that the Huns mastered siege technology and were able to attack and capture fortified cities by means of textbook Roman military tactics.”

The Hun’s attack and sacking of Naissus, the birthplace of Constantine the Great, is a great example of their genius. According to “End of Empire”: the Huns first crossed the river that protected part of the walls and then brought up tall cranes mounted on wheels. Shielded by light willow screens covered with raw-hide, men positioned high up on the arm of each crane were able to fire arrows directly over the battlements. Once a stretch of walls had been cleared of defenders, the cranes were replaced by battering rams.

Attila had smashed through the empire’s frontier defenses and brought his army within twenty miles of Constantinople. According to the sixth-century historian Marcellinus, the Huns “had attacked and pillaged forts and cities, lacerating almost all of the territory surrounding the capital.”

Interestingly though Attila didn’t push against Constantinople as it was still too fortified even for his army. Instead, he negotiated peace and an annual payment of 1400 pounds of gold, which is equivalent to $40M in today’s dollars.

Attila and his brother marched back to the Hungarian Plains, where Bleda was mysteriously killed in 445 CE. This gives Attila sole control over the Hun Empire and the vast horde.

The historian Jordanes described Attila at length in his 6th Century writings: He was a man born into the world to shake the nations, the scourge of all lands, who in some way terrified all mankind. He was haughty in his walk, rolling his eyes so that the power of his proud spirit appeared in the movement of his body. He was short of stature, with a broad chest and a large head; his eyes were small, his beard was thin and sprinkled with gray. He had a flat nose and a swarthy complexion, revealing his origin.

In the Worldhistory.org article, historian Will Durant translates first-hand accounts of Attila from the Greek writer Priscus: Attila differed from the other barbarian conquerors in trusting to cunning more than to force. He ruled by using the heathen superstitions of his people to sanctify his majesty; his victories were prepared by the exaggerated stories of his cruelty, even his Christian enemies called him the "scourge of God".

Jordanes details: “He could neither read nor write, but this did not detract from his intelligence. He was not a savage; he had a sense of honor and justice, and often proved himself more magnanimous than the Romans. He lived and dressed simply, ate and drank moderately, and left luxury to his inferiors, who loved to display their gold and silver utensils, harness, and swords. Attila had many wives but scorned that mixture of monogamy and debauchery which was popular in some circles of Ravenna and Rome. His palace was a huge log house floored and walled with planed planks, but adorned with elegantly carved or polished wood, and reinforced with carpets and skins to keep out the cold.

In 446, Attila again manufactures outrage with the Romans, breaks the treaty, and begins to capture forts along the frontier. He invaded the Roman region of Moesia, in the present-day Balkans. In the process, he destroyed more than 70 cities, took survivors as slaves, and sent the loot back to his stronghold at the city of Buda, which is thought to be modern-day Budapest. He was considered invincible and "having bled the East to his heart's content, Attila turned to the West and found an unusual excuse for war."

Joshua Mark explains the bizarre situation in his Attila article for worldhistory.org. In 450 CE, Roman emperor Valentinian's sister, Honoria, was seeking to escape an arranged marriage with a Roman senator. She secretly sent a message to Attila, along with her engagement ring, asking for his help. Although she may never have intended anything like marriage, Attila chose to interpret her message and ring as a betrothal and sent back his terms as one half of the Western Empire for her dowry.

Emperor Valentinian, when he discovered what his sister had done, sent messengers to Attila telling him it was all a mistake, and there was no proposal, no marriage, and no dowry to be negotiated. Attila asserted that the marriage proposal was legitimate, that he had accepted and would claim his bride, and mobilized his army to march on Rome.

Both the Eastern and Western Roman empire legions combined to meet Attila in the Battle of Catalaunian Fields.

Historian Jack Watkins describes the battle: The Romans, occupying the high ground, quickly succeeded in pushing the Huns back in confusion, and Attila had to harangue them to return to the fight. During fierce hand-to-hand fighting, King Theodoric of the Visigoths was killed. But rather than discouraging the Visigoths, their king's death enraged them and they fought with such spirit that the Huns were driven back to their camp as night fell. For several days the Huns did not move from their encampment, but their archers succeeded in keeping the Romans at bay. The desertion of the frustrated Visigoths allowed Attila to withdraw his army from the battlefield, and with his wagons of booty intact. The Romans did not pursue him, but his aura of invincibility had been shattered.

Attila returned in 452 CE to invade Italy and once again claim Honoria as his bride. Attila sacked much of northern Italy but stopped at the Po River. It is believed he stopped out of superstition or because famine was ravaging the region and he knew his army could not be fed. Emperor Valentinian sent Pope Leo 1 to negotiate with Attila. Not much is known of the meeting, but Attila turned his force around and again marched back to the Great Hungarian Plains.