Ad for Lane Bryant maternity apparel, Vogue, 1920, Feb. 1, pg. 141

I’ve never been pregnant, so I have no experience with wearing maternity clothes. However, a few weeks ago I was trying to learn to use the ProQuest search engine (courtesy of my public library.) Under “Fashion,” I typed in “maternity.” I now have quite a collection of articles giving maternity fashion advice from the 1920’s and 1930’s — and haven’t even begun to explore the decades before and after. The emphasis on “concealment” is striking.

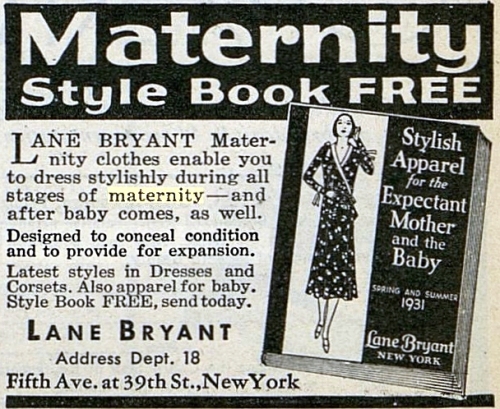

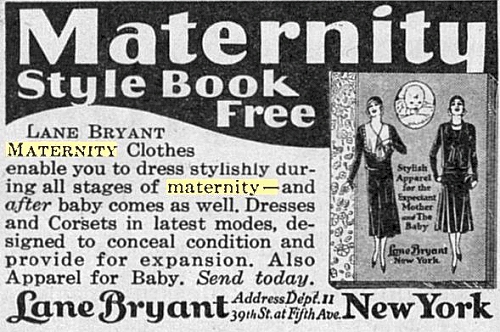

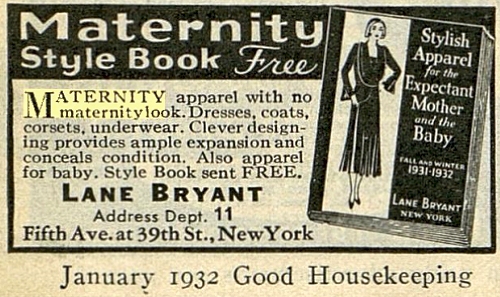

“Designed to conceal condition and to provide for expansion. “Ad for Lane Bryant Maternity catalog, Good Housekeeping, May, 1931.

“Clothes that are designed solely for maternity wear are apt to look the part, and call attention to a woman’s condition. At this time you do not want to be conspicuous in any way. You want to look as much like other women as possible so there will be nothing to draw notice to you. It is much better to choose current styles that can be adapted to maternity wear and use them in preference to special maternity clothes.” — The New Dressmaker, circa 1921, from Butterick Publishing Company via Hearth.

(Nevertheless, Lane Bryant had been selling maternity clothes since the early 1900s. See the company history at Funding Universe. (Caution from McAfee security about some ads on that site.)

“Dresses and Corsets in latest modes, designed to conceal condition.” Ad for Lane Bryant Maternity catalog, Good Housekeeping, May 1930.

“Maternity apparel with no maternity look… conceals condition.” Ad for Lane Bryant maternity catalog, Good Housekeeping, January 1932.

Of course, clothes that could also be worn after the baby was born were a good thing for the budget.

Confinement: Confined to Home

I’ve read enough Victorian novels to realize that women in the upper levels of society were expected to stop appearing in public once their condition became obvious — perhaps because contemporary fashion simply couldn’t accommodate an eight or nine-month baby bump, but also because this evidence of sexual activity was considered distasteful. (Playwright Louise Lewis discusses the old ceremony of “Churching” women to purify them after childbirth here; however, the ceremony was not exclusive to Catholics. A much more detailed examination of the practice can be found here.)

Modern mothers who are expected to leave the hospital the day after birth and resume their normal work routine may feel envious of women who once were expected to rest for a few days — or weeks. Depending on the era and region, a woman might be “confined” to her home for several weeks either before or after giving birth. (A brief article summarizing Victorian pregnancy practices for the upper classes can be found here. Queen Victoria herself gave birth nine times.)

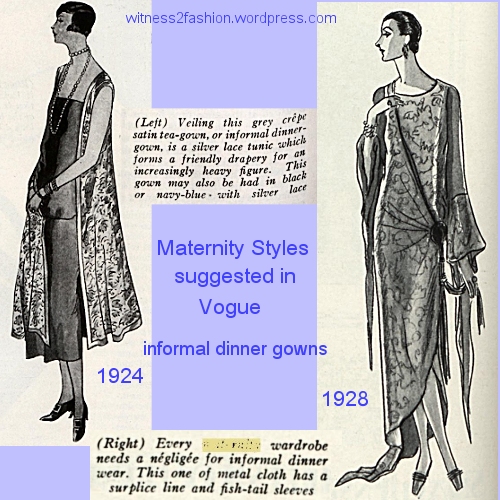

In an era when paying and receiving “calls” occupied a good portion of a lady’s week, receiving callers — in a tasteful tea-gown — meant that the mother-to-be was not completely cut off from social activity; friends came to her. Elegant tea-gowns or dinner-gowns were still prescribed in the 1920’s and 1930s.

Store-bought dinner-gowns or tea-gowns suggested for maternity wear; Vogue magazine, 1924 and 1928. The surplice line, right, (a diagonal front opening closed at the side) was often recommended for maternity wear. (I can just imagine those sleeves trailing through the soup….)

By sheer serendipity, you can read about tea-gowns from 1915 at American Age Fashion.

But what about daytime maternity dresses in the nineteen twenties? That tubular style, the distinctive low waist-line — often accented by a snug horizontal belt or band — how did that work with a baby aboard?

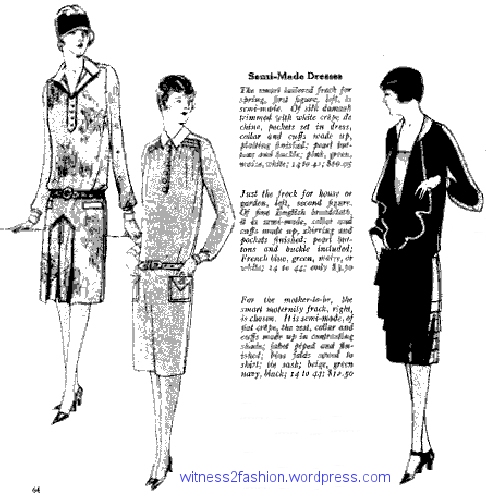

Three semi-made dresses, Good Housekeeping, March 1927, p. 64. The one on the right is a maternity dress. Sizes 14 to 44, $12.50. [This is a good example of why I hate microfilmed magazines! They do not digitize well….]

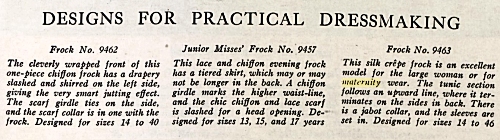

Vogue patterns 9462, 9457, and 9463. July, 1928. One is a maternity dress pattern.

Vogue, July 1928, page 75. Frock 9463, on the right, is a maternity pattern for sizes 14 to 46. [Sizes 14, 16, 18 and 20 were for teens and small women. Average sizes were sold by bust measure, e.g., 46 inches.] The dress in the middle is for teens to age/size 17.

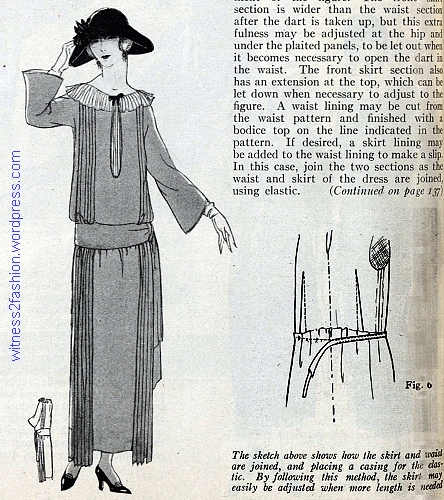

Earlier in the 1920s, Good Housekeeping offered a pattern for this maternity dress in an article about its construction. Oddly, the pleated panels seem to be decorative, rather than a means of expansion.

A maternity pattern from Good Housekeeping, August 1923.

“The pattern for this dress is cut in twelve pieces, as follows: two waist [bodice] sections; two sleeves; two skirt sections; a vest; a girdle [sash]; two strips for plaited panels for waist and skirt (front and back); a plaited [pleated] collar; and band for elastic. The front waist [bodice] section has a dart which takes care of some of the extra fullness thrown in to allow for the development of the figure. The front skirt section is wider than the waist [bodice] section after the dart is taken up, but this extra fullness may be adjusted at the hip and under the pleated panels, to be let out when it becomes necessary to open the dart in the waist. The front skirt section also has an extension at the top, which can be let down as necessary to adjust to the figure.”

Adding about three inches to the top of the center front of the skirt in a curve which tapers to nothing at the sides is actually a clever idea (if you don’t mind taking the dress apart at the waist seam every few weeks) since it adds length at the waist in front, keeping the hem even and untouched.

The girdle [sash] “should fold over at the hips, not tie. The ends should come well down the length of the skirt.” “Have strips for panels hemstitched and then plaited — fine knife plaiting which can be done by any of the small shops or by a department store. Be sure to caution the worker” that the pleats in the two panels should not all run in the same direction, but folding toward or away from each other. — Laura I. Baldt, “How to Make a Smart Maternity Frock” in Good Housekeeping, August 1923.

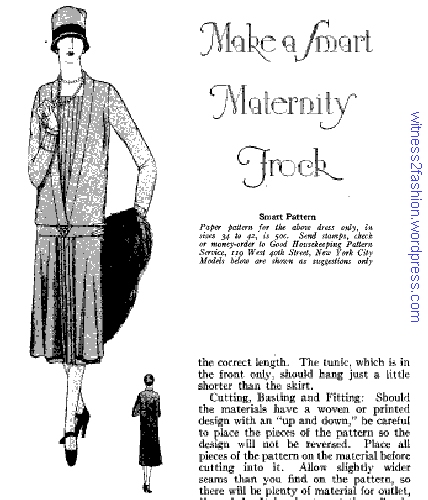

In July of 1926 Professor Baldt recommended this maternity pattern, also available from Good Housekeeping.

A Good Housekeeping maternity pattern, July 1926, p. 79. (Sorry for the photo quality.)

“It is a loose-fitting model, easy to put on and take off, and, with a few alterations from time to time, it may be adjusted to the figure quite easily.” “When it is necessary, the darts in the waist [bodice] lining may be let out; the plaits in the vest may be let out and also in the skirt, the last one being laid much deeper than the others for this purpose.The hem on the front of the tunic may be let out also, as it has a generous hem allowance to provide for this.”– p. 164

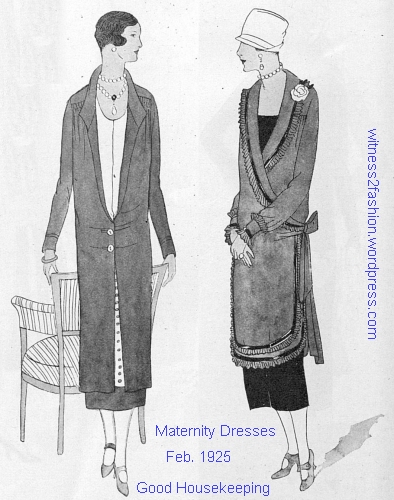

These made-to-order “Practical maternity clothes” could be ordered from Good Housekeeping Shopping Service in 1925.

Practical maternity dresses from Good Housekeeping, February 1925, p. 62.

“The dress above is a dark blue (also comes in black or brown) crepe de Chine coat effect over a beige under-dress, 36 to 46, $20.50. Gown at right is also of crepe de Chine, all colors, 32 to 42, $49.50. Both models are excellent in line for maternity purposes.”

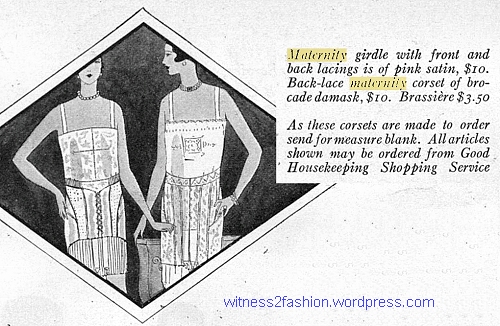

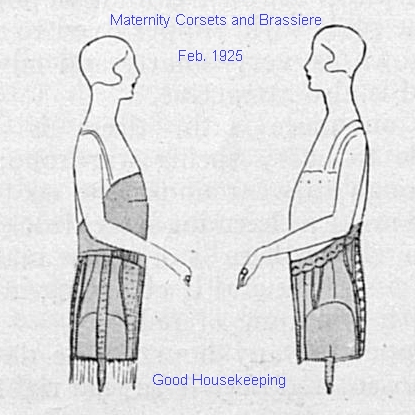

They would have been worn over a maternity corset — thought necessary for healthy support — like these:

“Maternity girdle with front and back lacings is of pink satin, $10. Back-lace maternity corset of brocade damask, $10. Brassiere $3.50. Good Housekeeping, Feb. 1925, p. 62.

Side views of maternity brassiere, girdle, and corset. Good Housekeeping, Feb. 1925.

Lane Bryant maternity corset ad, Vogue, Nov. 15, 1925, p. 159.

Some fun, huh?