WASHINGTON — If you invest in a retirement plan or a brokerage account, you most likely invest in mutual funds. The 2017 Investment Company Fact Book says, “In mid-2016 an estimated 94 million individual investors owned mutual funds — and at year end, these investors held 89 percent of total mutual fund assets.” Among those families owning mutual funds, the average amount invested in 2016 was $125,000.

It can be very confusing for any investor to figure out exactly how much they are paying in fees to a mutual fund. Since these fees can reduce your investment in the fund, affect your overall return or both, it’s important to have an understanding of what you’re paying for.

Should fees drive your investment decisions?

Before we move on, we want to briefly address the ongoing debate regarding fees. Certainly, no one wants to pay more for a product or service, and given the choice between two mutual funds with the same underlying investments and return, it makes sense to select the one with lower fees.

But fees should not be the only factor when deciding how best to invest your money. Some mutual funds may have higher fees but better total returns. Others may provide greater diversification by investing in unique strategies, such as alternatives or certain emerging markets where there may not be as much competition among mutual fund companies. When investing for our clients, we use a blend of lower-cost funds and funds that may have higher fees but we believe adding diversification and the potential for higher returns.

To untangle the web of fees, we put together this primer to help you determine just how much you’re being charged by companies you select to manage your investment dollars. Simply put, there are fees you can see and fees you can’t see.

Fees you can see

Shareholder fees are charged directly to the investor, which makes them easier to identify. Typically, these fees are collected as either a deduction from your investment account or reduction in the investment value. You can identify these charges by reviewing your brokerage account statements or trade confirmations. Several categories of costs may be charged, depending on how the fund is purchased.

- Initial Purchase Sales Charge (Front-end Load): Charged at the initial purchase and is usually passed through to the broker selling you the fund. This may also be referred to as a commission. This amount is deducted from the investment amount and reduces the total amount you purchase of the fund. The self-regulatory body called the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority states that a front-end load cannot exceed 8.5 percent.

- Purchase Fee: Similar to a front-end load, this fee is paid into the mutual fund assets, not to the selling broker. Like an Initial Purchase Sales Charge, this amount is deducted from the investment amount and will reduce the total amount you purchase of the fund.

- Deferred Sales Charge (Back-end Load): This fee is paid when you sell the investment. Like the front-end load, a back-end load is usually used to compensate the selling broker. The amount of this charge depends on how long you’ve held the fund, and usually decreases to zero if you hold onto the shares for a certain period of time. The most common type is called a contingent deferred sales load. This amount is deducted at the time of sale, so it does not affect the initial investment amount, but does reduce the amount you receive in proceeds from a sale.

- Redemption Fee: Similar to a back-end load, this fee is charged when an investor sells their fund shares. The main difference is that this fee is not passed on to the selling broker, but is added to the mutual fund’s assets. The SEC limits redemption fees to a maximum of 2 percent.

- Exchange Fee: Some mutual fund families will charge a fee if you change to a different investment, but remain with their fund family.

- Account Fee: A fee to cover costs to maintain your account. This may be charged for accounts below a certain dollar value or for special types of accounts, such as retirement accounts.

Fees you can’t see

Operating and other administrative fund fees stem from ongoing costs incurred by the mutual fund company. They are typically deducted directly from the fund’s assets, meaning you are paying these costs indirectly and in a way that is harder to track. Because you won’t see these charges on your account statement or trade confirmations, it’s harder to discern the annual expenses you are paying.

You can determine these costs by reviewing the Fee Table in the fund prospectus to know what’s being charged. Since these fees affect your overall return, you’ll want to be aware of them and the impact on the total performance return of each fund.

- Management Fees: Charged to cover fees to the investment adviser of the mutual fund for management of the fund’s investment portfolio.

- Distribution Fees (12b-1): Cover costs of marketing and selling shares. Mutual funds pay these fees to compensate brokers and others who sell fund shares. They also cover the costs of advertising and producing investor information, including prospectuses. Some funds also include the costs charged for providing services to shareholders.

- Other Expenses: Not included above to cover items such as fund-related legal fees, custodian expenses and other fees related to administration of the fund.

It’s important to note that an investment adviser representative of a Registered Investment Advisor firm cannot accept 12b-1 and other commission-based fees. As a fiduciary (also known as a fee-only adviser), they are compensated from the advice they provide to their clients, not on the investment products they recommend or sell to clients.

How share classes affect the fees you pay

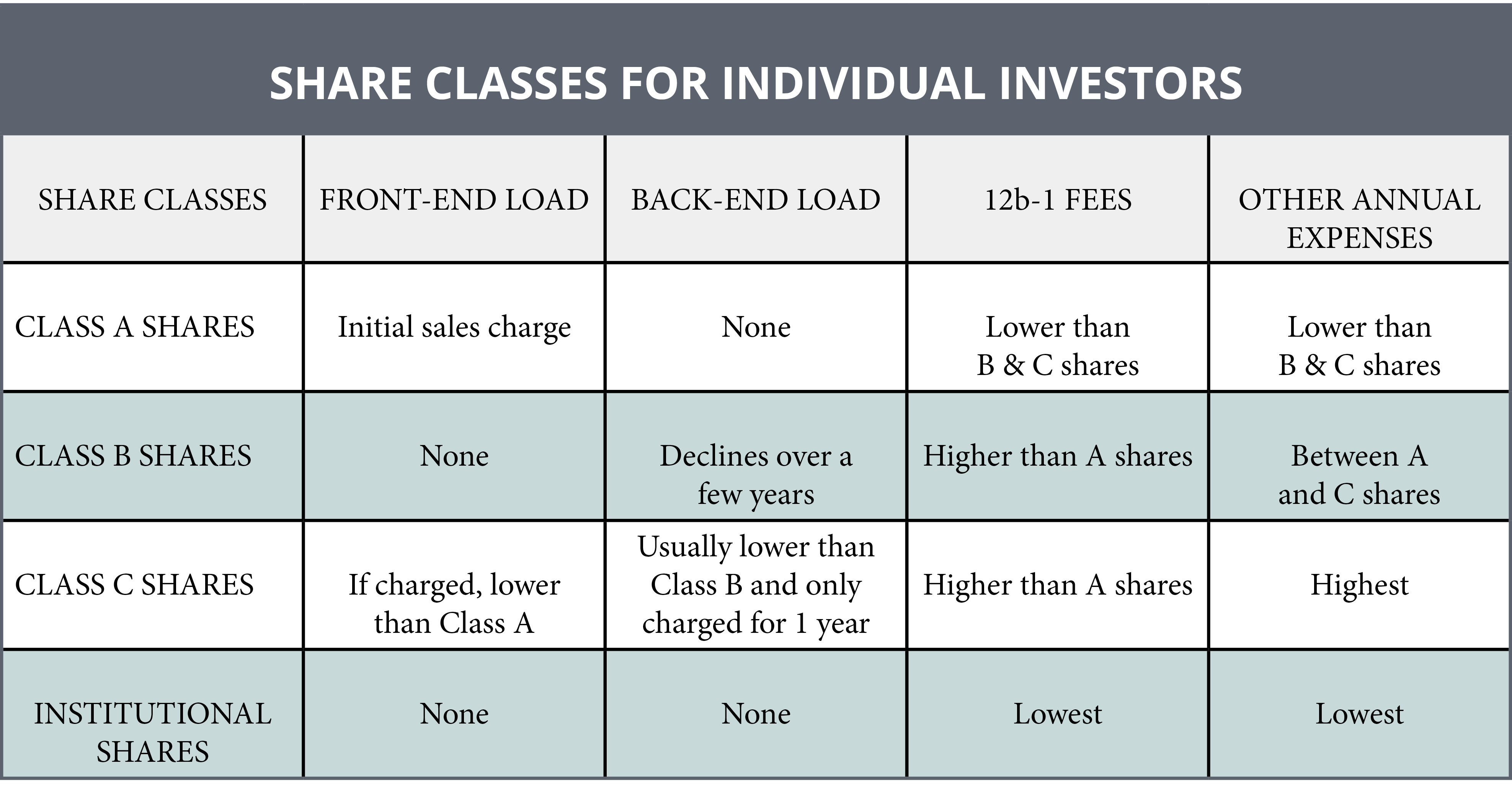

Fund companies collect these fees you can see (shareholder fees) and the fees you can’t see (annual fund operating fees) through a structure of different share classes, typically A, B, C and Institutional shares. While each share class invests in the same underlying mutual fund pool of investments, your returns will vary due to differences in the fees charged by each share class.

One of the main reasons different share classes are offered is to compensate brokers who sell them. Share classes also provide investors a way to select a fee arrangement that reflects their specific investment goals. The following are the most common share classes and how they collect fund fees from individual investors. Note there are a number of other share classes offered through retirement plans (i.e., 401ks), and those share classes have names and fee structures that differ from those listed below:

Your goals should determine what share class you choose

As the chart illustrates, each share class has a unique combination of front and back end loads, 12b-1 fees and other annual expenses. Your selection of the appropriate share class should be based on a number of factors, with investment goals and time horizon being important considerations.

For example, if you intend to hold a fund for a short period of time, it may not make sense to purchase an A share with a front-end load. Doing so would impose a one-time fee that may significantly affect your return if you don’t hold the fund for long. Conversely, longer-term investments may incur higher total fees if invested in C shares, as that structure tends to impose the highest annual cost.

Institutional share classes tend to provide the lowest overall level of fees and are typically only available through a financial adviser. If you work with a fee-only adviser, you will essentially replace sales commission fees paid to a broker with an advisory fee you pay to the adviser for ongoing investment and financial advice.

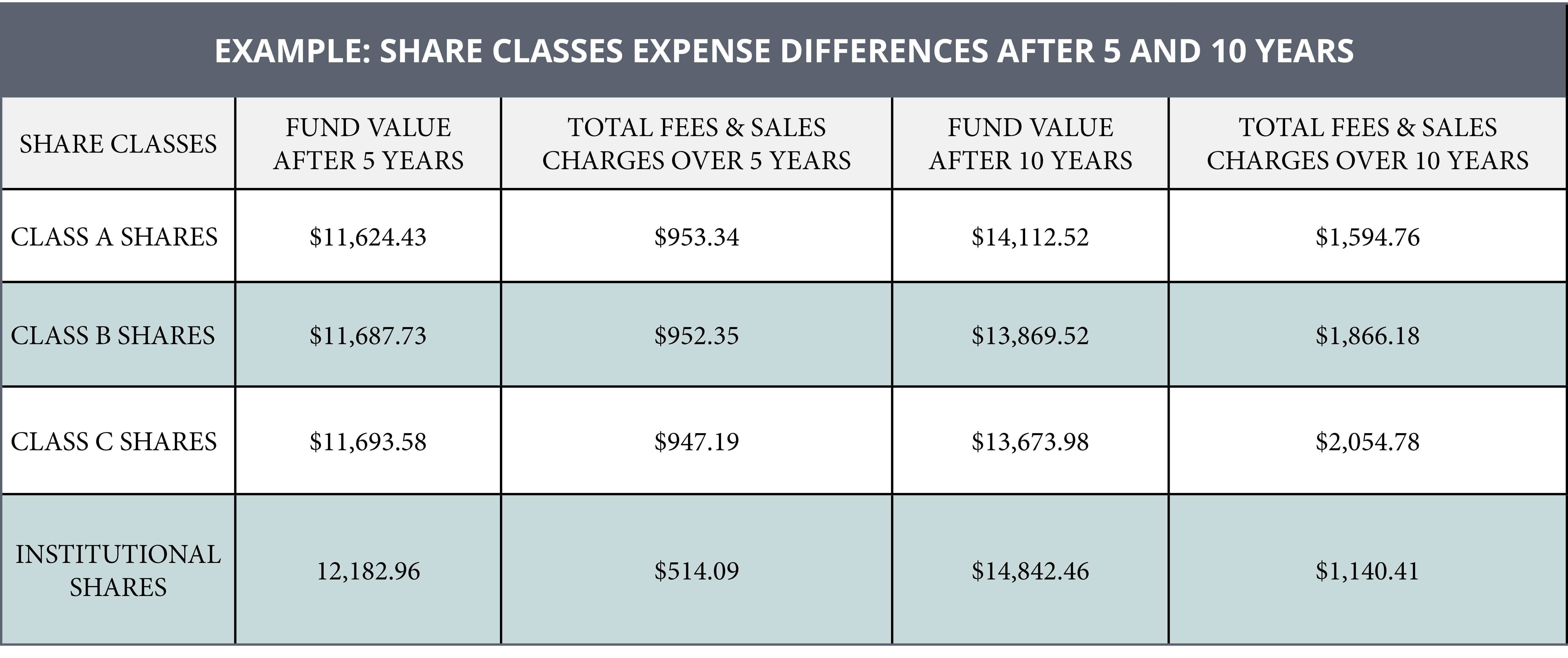

The following charts illustrate the importance of determining the time horizon of the investment before deciding which share class to buy. Due to the differences in one-time loads and annual expenses over a five-year period, your best choice for this sample fund would be an Institutional share class, with the second-best being a C Class fund.

Over a 10-year period, the Institutional share class still delivers the highest value for the lowest fees, but next in line would be an A Class fund. That’s because you have more time to amortize the front-end load you’ll likely pay on an A Class fund. The below table was calculated using the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority’s Fund Analyzer.

Putting it all together

Now it’s time for you to put this knowledge to practical use. Get your mutual fund statements and review them to understand what share classes you own and how you are being charged for your investments’ expenses. You’ll also want to review each mutual fund fact sheet or fund prospectus, typically available online, to know the total expense ratio you are paying for each fund.

The Securities and Exchange Commission requires mutual fund companies to disclose this information. You can determine the fund fee you’re paying by locating the Expense Ratio in the fund prospectus. Keep in mind that the Expense Ratio is composed of both the shareholder fees and the annual operating expenses. If you are working with an adviser, you can ask them to provide a list of share classes and expense ratios for each fund in your portfolio.

Fees should be one consideration, but not the only one, when deciding where to invest your money. Ultimately, your investment decisions should be driven by your goals and the best way to invest to achieve them. It may not always be with the lowest-cost fund.

Dawn Doebler is a senior wealth adviser at Bridgewater Wealth, in Bethesda, Maryland, and co-founder of Her Wealth.