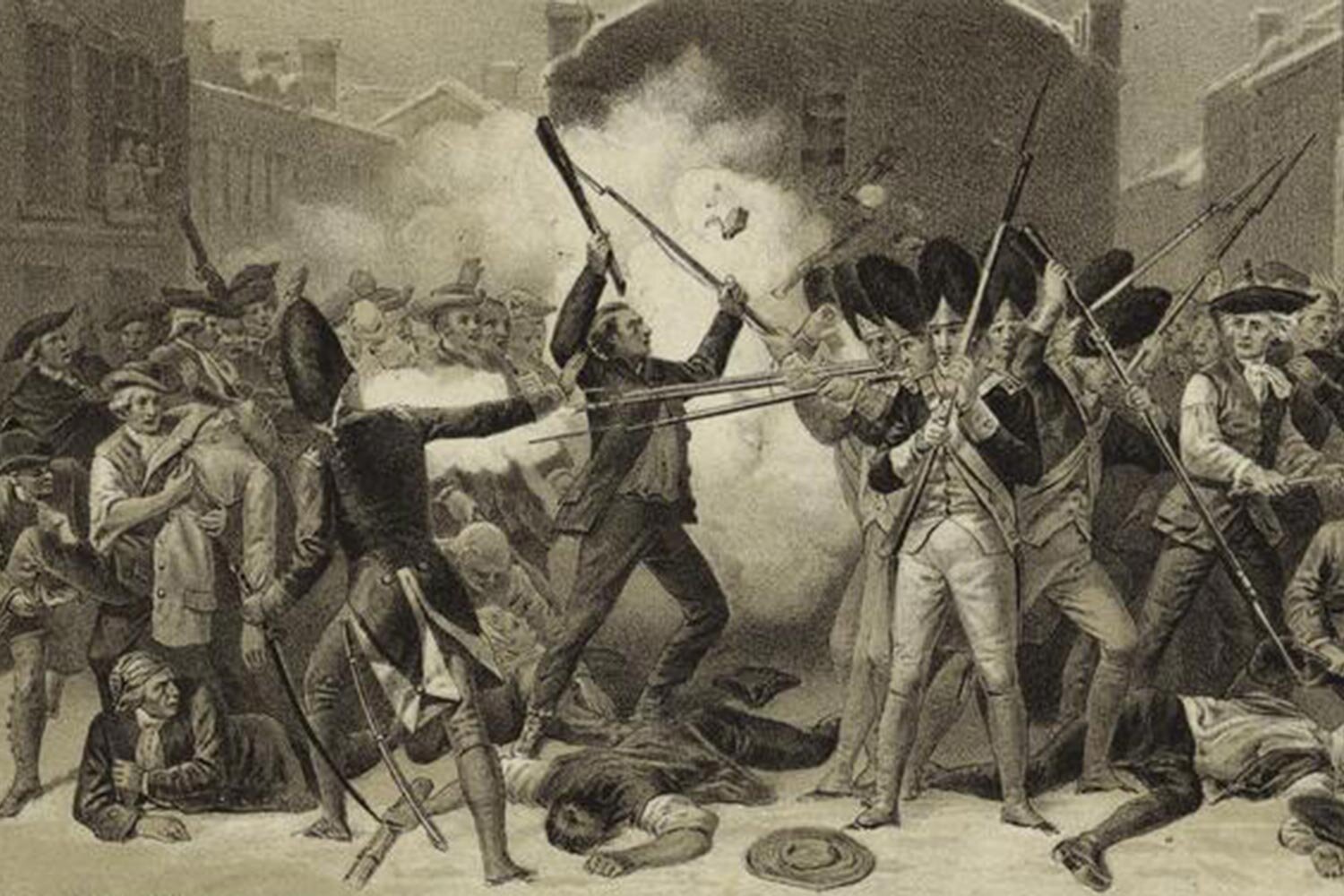

Mob Violence and the Boston Massacre

The Boston Massacre was a sad, tragic affair in colonial America and the facts surrounding the event are little understood today. It is a lesson in the danger of mob violence and how matters can quickly get out of hand when leaders do not act responsibly.

The background to the event can be traced to the Townshend Acts, a series of four laws passed by Parliament in June 1767. The Commissioners of Customs Act was one of these Acts, and its purpose was to allow officials to better enforce trade regulations and the collection of import customs and taxes.

Boston was a hotbed of smuggling, and men like John Hancock who were making money from these illegal activities strongly opposed the measures. They were joined in their resistance by others such as Samuel Adams who felt that Parliament lacked any authority to legislate for the colonies. Their followers, many of them with the Sons of Liberty, began to harass customs officials charged with collecting the taxes.

Due to this hostility, Royal Governor Francis Bernard requested troops be stationed in the city to protect British officials and help enforce the law. By May 1768, the 50-gun ship HMS Romney had dropped anchor in Boston Harbor, and, in October 1768, the first of four British army regiments had arrived in the city.

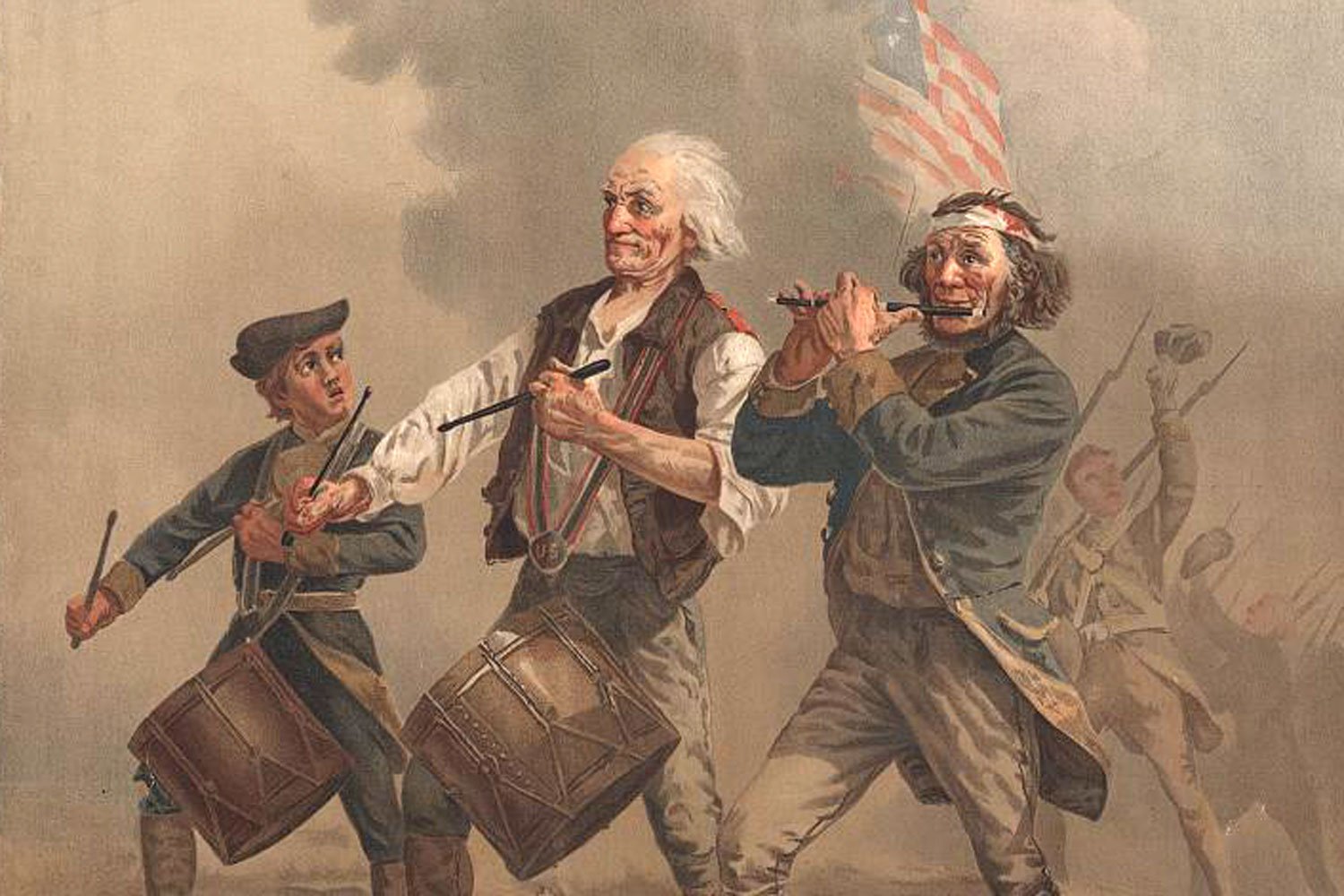

Keep in mind the stationing of active army units in American towns was a new habit, one that had not been practiced in the first 170 years of colonial existence. Prior to the 1763, when the French and Indian War ended, the British government had largely let its American colonies run themselves, a practice known as salutary neglect. We had learned to govern ourselves, and we liked doing it.

Naturally, Americans resented this perceived interference by outside authorities and their anger grew over the next year. The citizens of Boston began to view the soldiers as a hostile force, and they treated them in a rude and insolent manner. Not surprisingly, the soldiers disliked this treatment and began to push back. It was a powder keg set to explode when given the proper spark.

On February 22, 1770, a custom’s informer, Ebenezer Richardson, was being harassed by a group of unruly boys. These little urchins had pelted Richardson and his house with rocks and ice, breaking several windows and even striking his wife and children inside the house.

Richardson grabbed his musket and warned the boys and the men who egged them on to back off and go home. When the stone throwing continued, Richardson shot into the crowd killing a twelve-year-old named Christopher Seider just as the boy was picking up another rock.

Sam Adams and his propaganda machine went into action and made Seider out to be an angelic, innocent victim and tensions in the city rose. Over the next few days, there were several brawls between the soldiers and the citizens of Boston.

The morning of March 5, 1770, someone posted numerous handbills that were supposedly signed by the soldiers and threatening to harm the people of the city. No one knows who posted these, but it was almost certainly not the soldiers. More likely, it was someone wanting to stir the pot a bit more, and it worked.

That evening, a mob of about fifty people began to gather around Private Hugh White, a lone British sentry stationed outside the Customs House, simply doing his duty. They shouted obscenities and threats at White and dared him to fire his weapon. White called for help from his fellow soldiers. Meanwhile, some of the rioters began ringing church bells, a signal for the people to gather in the streets.

Captain Thomas Preston quickly dispatched seven more soldiers to aid Private White. By the time they arrived, the crowd size had grown to about 400. The Captain had his men load their weapons and fix bayonets, but he instructed them to hold their fire. Preston also pleaded with the mob to disperse but they would have none of it.

The mass of people continued to press on the soldiers, taunting them, and many in the crowd began to throw ice, snowballs, and oyster shells at this small group of nine men. One of the soldiers, Private Hugh Montgomery, was struck and staggered by a piece of wood thrown from the crowd. When he recovered his balance, Montgomery fired into the crowd, even though Captain Preston had not given the order. Other soldiers, believing the order to “fire” had been given, soon discharged their weapons as well.

When the firing stopped and the smoke cleared, eleven men in the crowd had been hit. Three of these died instantly, two more died within the next two weeks, while the others recovered. The shooting was all over in a matter of minutes, but the aftermath of this terrible event was just beginning and that will be our subject for next week.

Until next time, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” Love of country leads me.

Partly due to Benjamin Franklin’s testimony before the House of Commons, the Stamp Act, which taxed items such as newspapers and legal documents, was repealed by Parliament on March 18, 1766. Unfortunately, this conciliatory measure was immediately undone when Parliament enacted the Declaratory Act which reasserted that all laws passed by that legislative body were binding on the colonies, including those related to taxes.