Blaine Denning Sr. was 1st Detroit public high school basketball player drafted into NBA

The date was March 7, 1947. All eyes were on the State Fair Coliseum because, for the first time, two high school boys basketball teams with all-Black starting lineups were squaring off for the Detroit Metropolitan League title.

On the court making history that Friday evening, in front of 8,000 fans, were Sammy Gee, Clarence Norris, Harold Blackwell, Frank Robinson and Gene Hamilton, coached by Will Robinson for Miller High School, and Bill Williams, Blaine Denning, Larry Penson, Alvin Powell and Charles Redd, coached by Eddie Powers for Northern High School.

Led by the incomparable 5-foot-8 floor general Gee, a football standout and talented enough later to play baseball in the Brooklyn Dodgers’ farm system, Miller defeated Northern on the basketball court, 52-21. But the score may have been even more one-sided if a rising junior on Northern’s team had accepted a previous invitation to be a student-athlete at Miller.

“Coach Robinson wanted my father to play for Miller, but my father was a ‘North Ender’ through and through,” Blaine Denning Jr. said recently of his late father, Blaine Denning Sr. (Sept. 9, 1930-Jan. 25, 2016) who was born in Fulton, Kentucky. “The North End nurtured my father when he moved to Detroit at age 12. He knew the people; it’s where he started playing organized basketball, and he didn’t want to go to any high school but Northern.”

As it turns out, attending high school in the North End, where Northern — 9026 Woodward Ave. — was a neighborhood anchor, served Blaine Denning Sr. well. A 6-foot-2 forward, Denning Sr.’s play during his senior season earned him a first-team spot on the Detroit Free Press 1948 All-City League basketball team, along with Jim Mongeau (Cooley), Arnold “Skip” Domke (Mackenzie), Aram Sarkisian (Southwestern) and his Northern teammate, Chuck Holloway. After graduating from Northern, Denning Sr. would spend time at what is now Central State University in Wilberforce, Ohio, before returning home to enroll at Lawrence Institute of Technology, which was then located at 15100 Woodward Ave., within the former Henry Ford Trade School building at the Model T assembly complex in Highland Park.

At Lawrence Tech, Denning Sr. demonstrated his basketball prowess again, leading his teammates on a magical ride that included victories over Washburn University and Utah State to advance to the “Elite Eight” in the 1952 National Association of Intercollegiate Athletics basketball tournament. A year earlier, on March 10, 1951, the Lawrence Tech team visited the “Mecca of Basketball” — New York’s Madison Square Garden — where the team faced off against Dayton in a competitive first-round game of the National Invitation Tournament won by the eventual tournament runner-up Dayton, 77-71. Playing in front of the Garden’s bright lights, Denning Sr. scored 27 points against Dayton, setting the stage for his senior campaign, during which he averaged 20 points a contest.

Denning Sr.’s performances caught the eyes of talent evaluators at the highest levels of professional basketball during his day, including Abe Saperstein — founder, owner and earliest coach of the Harlem Globetrotters— and the Baltimore Bullets (known today as the Washington Wizards), which selected Denning Sr. with the team’s second pick in the 1952 NBA draft, making him the first player from a Detroit public high school to be drafted by an NBA team. In the case of the Globetrotters, a team good enough during that era to defeat the storied Minneapolis Lakers twice — in 1948 and 1949 — the interest in the Lawrence Tech star was facilitated by the same Miller High School coaching legend who set out to contain Denning Sr. during that historic high school championship game on the State Fairgrounds in 1947.

“I have the letters Will Robinson wrote to Abe Saperstein recommending my father and (Gene) ‘Big Daddy’ Lipscomb, whom he coached (in basketball and football) at Miller, for the Globetrotters,” said Denning Jr., who spoke on Feb. 21 from the Don Ridler Field House — named after his father’s college coach — on the campus of the now Lawrence Technological University, now in Southfield. “My father had a great relationship with Will, even though he never played for him. And that’s how it was between Miller (located at 2322 Du Bois St. in the area then known as Black Bottom) and Northern. It was a fierce rivalry, but it was a friendly rivalry because everyone knew each other.”

The correspondence from Robinson to Saperstein, a “National Basketball Association Uniform Player Contract” from the Baltimore Bullets, stories detailing Blaine Denning Sr.’s basketball journey, and more can be found in a thick scrapbook contained in a white binder that Blaine Denning Jr. brought to the Lawrence Tech Field House on Feb. 21. Denning Jr. jokes that the basketball gene skipped over him and landed on his son, Blaine Denning III, whose clutch 3-point shots helped Cass Tech High School win the 1998 Public School League championship at Cobo Arena in an overtime thriller versus Central. But Denning Jr. said he received his own precious gift when his father gave him five boxes of materials roughly 30 years ago that would ultimately fill Denning Jr.’s scrapbook.

But first, Denning Jr. had to make the time to go through it all to see what he had.

“When I was young, my father really didn’t talk about his basketball days,” recalled the 71-year-old Denning Jr. “People around me let me know what kind of a great player he was, but my father wouldn’t say much. Then, one day in the early 1990s, he gave me five boxes of stuff in no particular order and he said, ‘You may want to do something with this one day.’ Those boxes sat in my basement for a number of years."

"But when my father suffered a stroke in 1998 and couldn’t talk, I took it upon myself to sort through them because I wanted his grandsons (Blaine Denning III and Kyle Askew Denning) to know what he had done. And once I started, it all became real to me.”

Denning Jr.'s exploration of the items in the boxes led to conversations with respected Detroit elders, including the late Orlin Jones (Sept. 27, 1932-June 21, 2023), who is reverently remembered by many as “Mr. Conant Gardens” for his immense knowledge about his lifelong neighborhood and other Detroit treasures; and the late “Jumpin” Johnny Kline (Nov. 18, 1931-July 26, 2018), who starred in basketball and track and field at Wayne State out of Northeastern High School and later founded the Black Legends of Professional Basketball Foundation.

Through all of his research, Denning Jr. said he came away with a deep appreciation of his father’s talents and the talents of the local players who played alongside and against him. Denning Jr. says there is no denying that his father faced barriers that capped how far he could rise in the game of basketball. For example, as a member of the Globetrotters in 1952, Denning Sr. played in a game versus a team of College All-Americans that attracted 17,087 fans to the old Olympia Stadium, which, at the time, was the largest crowd ever to watch a basketball game in Detroit. However, Denning Sr.'s time with the Globetrotters was short-lived due to the extra showmanship that team members were expected to display.

“My father didn’t want to do tricks,” said Denning Jr., who later explained that his father’s way of expressing joy while playing was through a natural smile. “Dad just wanted to play basketball and he liked to score.”

Then there is that contract from the Baltimore Bullets, which Denning Jr. has preserved in the binder. The contract shows Denning Sr. was to be paid $4,500 — the equivalent today of about $52,000 — for the 1952-53 season. But the bigger issues facing Denning Sr. in the NBA, which did not integrate until the 1950-51 season, revolved around the number of African Americans that a team was willing to retain on a roster and put on the court at one time.

“Those were still Jim Crow days,” said Denning Jr., whose father managed to produce five points and four rebounds in a mere nine minutes in a game he played for Baltimore during the 1952-53 season. “Back then it was the quota system (for Black players): ‘two at home, three on the road, four if we’re behind.’ ”

On Feb. 22, Denning Jr.’s statement was supported by Bill Hoover Jr., a Detroit Public School League basketball historian and creator of the detroitpslbasketball.com website. Hoover’s research of Detroit’s connection to professional basketball goes back to a time before the league name National Basketball Association even existed, which includes Howard McCarty out of Wayne State, who from 1945 through 1947 played for Cleveland and Detroit teams in the National Basketball League and Basketball Association of America, which merged in 1949 to form the National Basketball Association. Hoover can reel off statistics and vividly describe events from decades ago. Still, when he talks about the era when Denning Sr. played collegiately and professionally, Hoover sounds more like a social scientist as he breaks down the role race played in basketball.

“Detroit’s basketball in the 1950s was a decade largely played in the abyss of racism,” said the 55-year-old Hoover, who since 1995 has pored through information and conducted interviews with people intimately connected to basketball in Detroit. “We produced a lot of professional basketball players with the Harlem Globetrotters and Goose Tatum Harlem Roadkings. This was ‘real’ pro basketball talent, and during that time, we also had some great teams at Wayne State, Lawrence Tech and the University of Detroit. In addition, Detroit's talent contributed to some strong HBCU teams.

“These men just played too early to have been welcomed in the majority white colleges and the NBA in appropriate numbers.”

In the case of Denning Sr., Lawrence Technological University has done its part to ensure that his athletic accomplishments and legacy are preserved in an “appropriate” manner, which included Denning Sr.’s enshrinement as part of the inaugural LTU Athletic Hall of Fame Class of 2011. It was an honor that Denning Sr. was able to fully soak up a couple of years later at Lawrence Tech.

“I took my dad to a basketball game and it kind of freaked him out because he had never seen the school in Southfield. And then he saw women, which he didn’t see during his days as a Lawrence Tech student,” explained Denning Jr., whose father, born Blaine Mitchell Jr., adopted the name “Denning'' to honor his aunt, Fern Denning, who raised him. “He was able to see his jersey No. 14 up in the rafters. And then, when the Lawrence Tech players were warming up, they all shot hook shots — my dad’s deadliest shot — to honor him.

“Dad was really choked up and people around us who probably didn’t know anything about my dad until that moment, were choked up.”

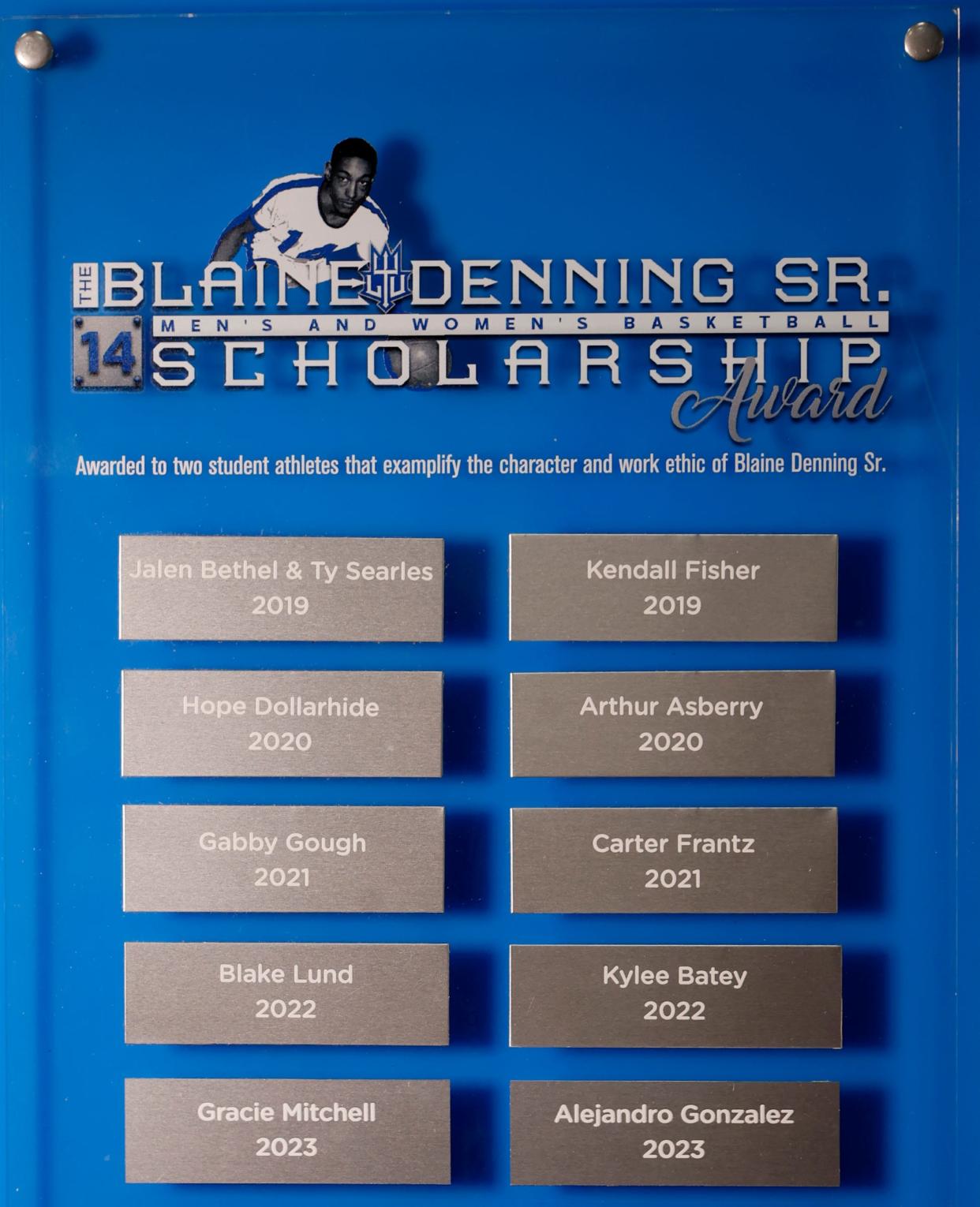

During the evening of Feb. 20 at the Lawrence Tech Field House, no tears came from Denning Jr. and his wife, Rosalind Denning. However, a look of immense pride could often be seen on their faces, particularly when they stood next to a plaque in the lobby area that displays the names of the male and female student-athletes representing the Lawrence Tech basketball team that have received scholarships since 2019 in the name of Blaine Denning Sr. The scholarship is not only a reminder of who Denning Sr. was as an athlete, but it also reflects who he was as a man, which included being a successful entrepreneur in Detroit as the operator of a wholesale milk distributorship that branched out into other ventures. In addition, Denning Sr. was a community servant as revealed by a page in his son’s scrapbook that shows Denning Sr. and his late wife, Dr. Bernadine Denning, as past recipients of the Distinguished Warriors Award presented by the Urban League of Detroit & Southeastern Michigan to people that have made lifetime impacts in the areas of civil and human rights.

“The scholarship makes me beam with pride because he (Blaine Denning Sr.) was a trailblazer,” said Rosalind Denning, who is the board chair for the Black United Fund of Michigan, which is committed to supporting youth empowerment programs for underrepresented and underserved youth. “He paved the way for many, many athletes. And Bernadine Denning and my father-in-law were very giving people. So, when they both passed, we wanted to keep their names alive, and keep their legacies alive, and provide some history to the young people that are coming up.

“We make it a point to personally get to know all of the scholarship recipients, to offer them any assistance they may need, to mentor them if we can, and to keep them encouraged. And we let them know that they have to give back as well.”

Scott Talley is a native Detroiter, a proud product of Detroit Public Schools and a lifelong lover of Detroit culture in its diverse forms. In his second tour with the Free Press, which he grew up reading as a child, he is excited and humbled to cover the city’s neighborhoods and the many interesting people who define its various communities. Contact him at stalley@freepress.com or follow him on Twitter @STalleyfreep. Read more of Scott's stories at www.freep.com/mosaic/detroit-is/. Please help us grow great community-focused journalism by becoming a subscriber.

This article originally appeared on Detroit Free Press: Blaine Denning Sr. made Detroit history getting drafted into NBA