Despite its context of colonial extraction, Bahrain’s first sand golf course demonstrates attitudes to landscape that the region would do well to adopt

If one were to compare institutions left in the wake of the British Empire, golf clubs are perhaps among the more seemingly innocuous. Yet, unlike other recreational pastimes made popular under British influence – cricket and football, for example – golf does not take place within an easily reproduced boundary like a pitch or court. It requires an entire manicured landscape turned into a gaming surface: bunkers, hummocks, mounds, dells and lakes, punctuated by nine or 18 holes. The instantiation of the sport has several layers of embodied energy, from the initial creation of the course to the daily maintenance of the landscape. The problematic nature of the sport is even more evident in the deserts of the Arabian Peninsula, where the usual questions of exclusivity and classism associated with golf are compounded by a host of broader issues that make it an embodiment of the relationship between state, extraction, landscape and ecology.

Among the Arab Gulf states, the island nation of Bahrain – a British protectorate until 1971 – was the first to discover oil in 1932, and golf followed soon after when explorers settled near the oil well in the country’s rocky interior. By 1934, a refinery building for the Bahrain Petroleum Company (Bapco) was under way and plans for a permanent camp designed in a suburban bungalow fashion were drawn up. In between the refinery and what would be the expat company town of Awali was a stretch of desert and limestone outcrops that began to be used for impromptu golf games by the British and American oil explorers to pass the time. Informally inaugurated in 1937, the club sent a request through Bapco to the British Political Agent in Bahrain, asking to officially reserve the golf course land for ‘recreational and agricultural use’. After approval from the Sheikh, the land was granted to Bapco. Eventually, a club constitution was written and ratified in 1957, officially forming the Awali Golf Club.

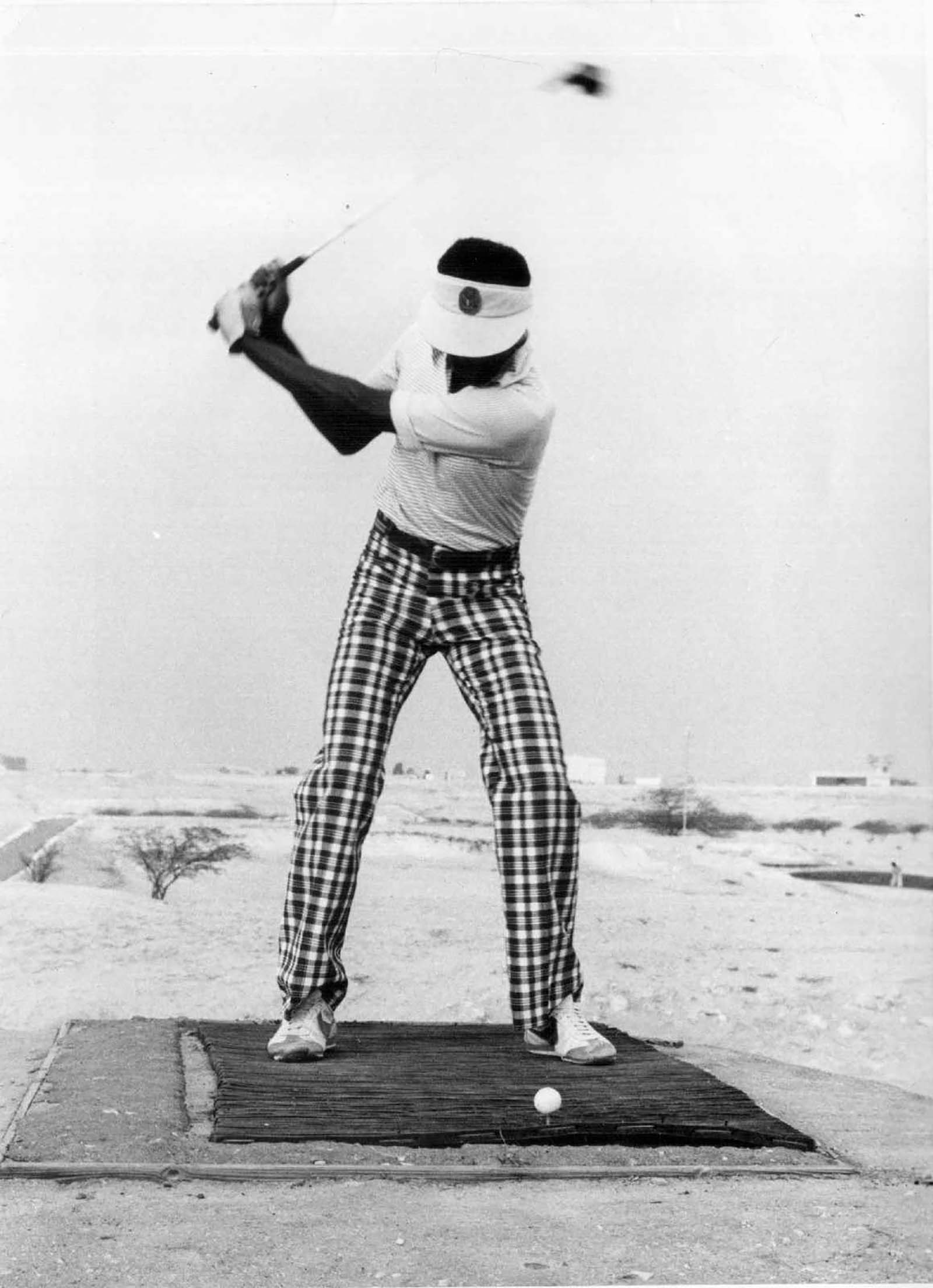

Players at the Awali Golf Club use their own patches of artificial turf to protect clubs from sand and pebbles

The course was not open to all. For the first three decades, Bahrainis could only experience the sport as caddies. Boys and young men from neighbouring Riffa were paid to carry golf bags for Awali Golf Club members and it was only after a group of caddies formed their own competing golf group within the Riffa Sports Club in 1961 that Bahrainis were considered sufficiently skilled to inhabit the Awali landscape as players, rather than as workers.

Awali, the town, was built using water from an aquifer, pumped several kilometres to the town from a source near the coastline. The water was used for drinking, plumbing, landscaping and air conditioning. The golf club, on the other hand, was a simpler endeavour. Given the scarcity of water, and the nature of the desert environment, it was decided to make a sand green – a golf course using sand mixed with oil for putting surfaces rather than grass – as an inexpensive, easily maintainable alternative.

The oil greens need to be laboriously maintained after every game

Today, visitors park their cars at the bottom of a verdant hill with the initials of the club, AGC, planted in white flowers. At the top of the hill is the golf clubhouse, complete with offices, a bar and gathering areas. Passing through the trophy room and souvenir shop, the visitor emerges at the top of the little hill, eyes adjusting to the albedo given off by the smooth white sand. The course is visible almost in its entirety through the columns of the patio, with a driving range to the right, holes ahead, and the black silhouettes of oil infrastructure in the hazy distance. The tee box is a plastic rectangle of artificial turf, raised off the ground by a concrete plinth. The fairway is made up of sand sourced locally and compacted on site, cleared of rocks and with its edges demarcated by a thin line of cement in some areas, or black crude oil mixed with sand in others.

Within the fairway, golfers drag their equipment and carry their own artificial turf mat to their tee offs; these prevent them from damaging their clubs on the sand and pebbles. Each hole has its own design and hazards, while the bunkers are small artificial hills or pits edged with tarmac or ‘oiled’ lines. The roughs, aptly named, are rocky areas, tarmac and road, or an errant pipe. The putting green is the most notable aspect of the course, as it is technically a putting brown, made up of fine sand mixed with 11 parts diesel and one part motor oil. The mixture keeps the sand in place and provides a smooth putting surface, emulating closely cropped grass. This brown circle has to be relaid weekly. After a golfer has finished, an allocated sweeper at each hole has to rake then smooth the surface before the next golfers arrive.

Sand greens like the one in Awali are not unique to Bahrain. Similar courses were established in Cairo during the First World War, and in the North American Great Plains during the drought-ravaged 1920s. Regionally, however, Awali was the first sand green, followed by similar courses constructed by oil companies such as Saudi Aramco and Qatar Petroleum. It was only after the introduction of desalinated water in Bahrain, and with increased oil revenue and tourism following the Gulf War, that grass greens were introduced to the country. The first green golf course in Bahrain – the Riffa Golf Club – opened down the road from Awali in 1999. Less than a decade later, it was closed down and its surroundings redeveloped into a luxury residential complex, Riffa Views. In 2007, the golf course was redesigned by Scottish golfer and course designer Colin Montgomerie, and rebranded as the Royal Golf Club. The developer’s advertisements read: ‘It’s like Scotland, minus the weather.’

Today, arid landscapes around the world are being terraformed to sustain a global idea of golf as a luxury pastime. Riffa Views Royal Golf Club, down the road from Awali, boasts of its Scottish-style greens

In contrast to the sand greens, the newer courses insist on a global idea of golf and the luxury of playing on grass. Rather than using oil for the creation of a smooth green, the new courses take an alchemical approach, converting the oil to energy and then water, desalinating and irrigating an otherwise arid landscape. Ironically, despite having been semi-colonial spaces administered by oil company officials, the older courses conceded that golf was an experience embedded in the local landscape – even if that landscape was mostly sand and rock. Adapting the game to the context was a matter of economy, as well as an effort to create a separate experience, rather than a recreation of a Scottish green. Expensive oil prices, easily available desalination, and a desire to match global standards has prompted the creation of the new golf courses. All countries in the Gulf now have grass greens.

In a country where almost all usable water has been desalinated or treated since 1975, Awali Golf Club’s insistence on sand greens is not only easier, but more responsible. While the township aimed to recreate a suburban experience with its landscaping, pools and cinemas, the golf course retained the desertscape and imagined a new version of the sport as an alternative to irrigating an entire field of non-native grass. The imaginary of golf had to change, not the landscape. Of course, sand greens are not entirely sustainable as a venture, given the regular mixing and reapplication of oil on local sand, and the need for several labourers to maintain each hole. But the course is still a largely self-sustaining topography, as opposed to the surreal illusion of a green course where there should not be one.

Emirates Golf Club in Dubai – the first green golf course in the Middle East – demonstrates a particularly stark contrast between desert and golf course when viewed from above

Credit: David Cannon / Getty

The question of self-sustaining landscapes has re-emerged recently in the wake of announcements, across the Gulf, of plans to achieve carbon neutrality by 2060. Planting trees to offset emissions, public park building, and reducing emissions are all strategies that have been put forward. These ambitions, coming from countries that are deeply implicated in the global ecological crisis, are well intentioned. However, they too risk falling under the grass green golf strategy. Carbon neutrality calculations tend to conveniently ignore the process of desalinating water, the importation of fertilisers and soil, and the continued maintenance of landscapes to offset carbon. In some cases, such as Bahrain’s recent ‘green campaign’ to plant thousands of trees, the championing of afforestation ignores the implications of water-intensive plants such as palm trees, which would not offset the carbon required for their own irrigation, let alone emissions from exported petroleum.

Sand greens and grass greens in the Gulf are an analogy for the complex of global metrics, international standards, and the aspirational qualities that certain landscapes can embody. It is ironic that the Awali course, which was established by oil explorers, actually provides a specific and contextual experience, while its newer neighbour offers generic fields that can be found anywhere. It represents a view of the planet in which landscapes are not interchangeable, where moraines and grasslands are not managed in the same way as deserts, scrubland and oil fields. On its own terms, the Awali Golf Club is an almost banal vision of sustainability; it suggests that the better venture could simply be to agree that the existing landscape is fine as is.

Lead image: Bahrain’s Awali Golf Club was established shortly after oil was discovered in the country in the 1930s. Its putting green uses a mix of sand and oil to recreate the smooth surface of closely cut grass. Credit: Camille Zakharia

The author wishes to thank Awali Golf Club Administration, Onny Martin, John Loughnane, Dr Isa Amin, and Ali Al Kaabi

Architectural Review Online and print magazine about international design

Architectural Review Online and print magazine about international design