LITTLE ROCK — After steering smartly around a dried up armadillo melted into the highway, I noticed a familiar structure on the right.

“There used to be a missile base up there,” I said to my daughter, pointing toward a cattle guard, a grate set in the road entrance to keep cows in their place. She looked mildly dubious. Or perhaps uninterested.

Not surprising; it wasn’t an imposing thing. The frame of welded iron marked the entrance to an unseen location beyond what looked like a dell and over a rolling hill. It wasn’t grand enough, big enough, scary enough, to have guarded a device that, if loosed, could have started the apocalypse. It all seemed too important for the middle of nowhere, near Mount Vernon, off Arkansas 36 in Faulkner County.

That device was a liquid-fueled Titan II missile, sitting in ominous quiescence in its concrete silo, capped by a multi-megaton warhead. It was part of a network of 18 silos across the north central part of the state. All were operational by 1963. They ended their service life almost 25 years later, in 1987.

As a late baby boomer, or as I prefer, a member of the Blank Generation, growing up in the 1960s and as a sullen nihilist teen in the ’70s, nuclear war was always just over the horizon.

Literally, in my case.

Over the hill, southwest of my house, was a missile base.

Too young to remember the Cuban missile crisis, I heard about it from my parents. We were living in Florida at the time, ground zero for an invasion of Cuba or a nuclear strike courtesy of the bearded, cigar-chomping Fidel Castro.

My parents described the convoys of soldiers moving south and the tension suspended in the humid Florida air.

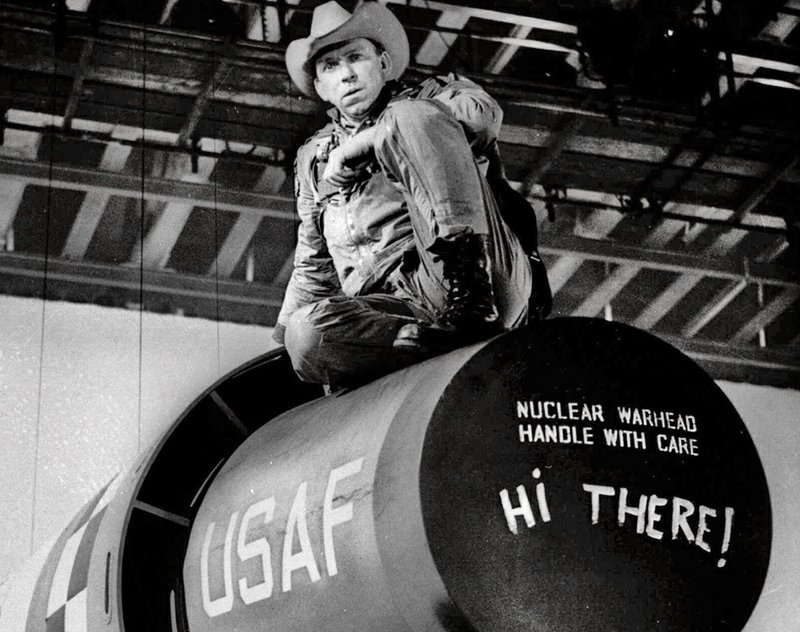

I was creepily thrilled secondhand, years removed from that nervy time, when the U.S. was prepared to go “toe-to-toe with the Rooskies,” as actor Slim Pickens succinctly put it in Stanley Kubrick’s movie Doctor Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb.

A cultural touchstone for cold worriers of my generation, the image of Slim riding an H-bomb bronco, waving his cowboy hat all the way to vaporization, encapsulated the surreal time. It was one of the charms of Doctor Strangelove, a hilarious comedy about nuclear obliteration. Because laughter’s the best medicine.

Watching these sorts of movies instilled a certain titillating anticipation, but my preteen self never felt the existential dread dredged up during modern discussions about the Cold War.

Mostly, I felt on the cusp of something.

That something was nuclear war. But that sounded too ... clinical. I preferred to call it the end of the world.

As a 9-year-old, I had no illusions, at least in regard to nuclear war. If the end game came, I would die, right there in secluded northern Arkansas.

I knew this because we were less than an hour’s drive from a U.S. Air Force base. With thousands of atomic cards in their deck, the Russians could certainly spare a couple of jokers for our Little Rock Air Force Base.

At the time I knew that a megaton is the explosive equivalent of 1 million tons of TNT. But depending on the megatonnage and the aim of the Russians, we might survive the air base strike. Commies weren’t known for accuracy then; they made up for it with bigger warheads. If they missed badly, very badly, we might survive.

But that scenario became moot; there was another reason to shower us with radiation.

The existence of those missile bases, tucked behind our green cattle-strewn hills, wasn’t a secret.

Certainly some fanatical Ivan had a cow patty-load of missiles aimed at the bases and, by extension, us. The nearest silo was about 10 miles away from our little white house in the woods. Too damn close.

I accepted this and still thought the whole thing was cool.

A most vivid childhood memory is a nuclear Huck Finn moment: I sat on a moss covered rock, dangling my feet in a slow-moving creek on the lookout for crawdads. All I needed to complete the tableau was a cane pole and a straw hat.Maybe Huck Finn pulling faces behind me.

But what made it memorable wasn’t the crawdads. A B-58 Hustler bomber streaked overhead, at treetop level, with a stupendous, thunderous, rushing shriek. It was terrifying and sublime. I jumped to my feet, trying to keep the plane in sight through the trees, but it was gone in an instant.

It took my breath away.

The long since retired Hustler was a supersonic bomber. It was built to outrun and evade Soviet interceptors. The plane had issues, I’d read, but it looked menacing and sexy.

The 43rd Bomber Wing’s Hustlers at LRAFB were ready to deliver their atomic death eggs onto mother Russia at a moment’s notice.

When I was 8, death was something I had no direct experience of. All I knew was that when those sleek shiny jets sparkled in arcs across the sky, when the Atlases and Titans erupted from their silos and thundered to the edge of space, that everything would go boom in a flash of light so brilliant it would blind the world.

The whole process was terribly fascinating. And it still is. It seems odd to fondly remember your childhood as a great roulette spin, Russian style, with a gun held against the entire world’s head.

It should be no surprise that my favorite literary genre was, and still is, the post-apocalyptic story. I’ve read the cheesiest of them, the oldest ones, the newest ones, the horribly dated ones.

I regularly re-read the classics Alas Babylon, A Canticle for Leibowitz and Level Seven. I think Whitley Strieber and James Kunetka’s War Day is a Reagan-era classic, regardless of the strange path Strieber skipped down later.

As the Cold War thawed to room temperature, for me, in book or movie form, it no longer had to be nuclear holocaust. Any sort of apocalypse would do. Asteroid strike, alien invasion, deadly plague, a deadly coup by the cast of Hello, Dolly. But the bomb is still the sentimental favorite.

Reading such fiction, you learn that no one is perfect, especially survivors of nuclear war. The stress level is high. Things are uncertain. Will you, dear reader, survive amidst a pile of books and then break your glasses?

What if the sole surviving woman you’ve found is named Eve and your name isn’t Adam? Does that mean you can’t repopulate the world?

Thwarted desires and the last man/last woman tale are part of a long list of ironic plot twists and wink-wink scenarios.

For example, after a disaster of global proportions, only the evil survive and prosper. People who’ve been clerks and Taco Bell managers, having read Machiavelli during break time, are ready to seize power.

Also surviving is a supply of hapless dupes.

Soon these pimply despots have dispatched their motorcycle riding, leather-clad hordes down desolate desert highways, looking for dupes. Or in a worst case scenario: Dupes, it’s what’s for dinner!

I’m not sure why motorcycles and leather riding outfits survive the rigors of nuclear war better than, say, racing bicycles and skin-tight Tour de France gear, but lots of stories, especially in the movies, cannot resist the look.

Besides, who would be frightened by a silent-but-deadly pack of starving 10-speed maniacs in clingy shorts?

A favorite plot theme during the late ’50s and early ’60s was the wildly disparate group of atomic survivors. In those days, in the midst of the civil rights movement, these stories made the point that old prejudices must be put aside.

Admirable, but the, um, terminology used and the convoluted condescension are cringe inducing these days. Understandable, given the times and the social climate, but it makes for uncomfortably anachronistic reading.

Another popular plot line is the hundreds-of-years-in-the future post-apocalypse story. Probably the finest example is A Canticle for Leibowitz by Walter Miller.

Miller’s postwar world violently rejects science and technology. Reconstruction and resurrection proceed, based on incomplete and misunderstood bits of the past.

The long dead prewar St. Leibowitz left behind a handwritten list that has been puzzled over and lovingly illuminated by generations of robed monks. The atomic irony: It’s a grocery list.

The point of this type of story is that we make the same mistakes over and over again, with the same sad results.

Now that we’ve “won” the Cold War, our apocalypses have changed. Other, more natural disasters are de rigueur. If these disasters produce zombies as a grisly by-product, all the better.

But the only surefire method we have to end the world, the quickest and most efficient, is the A-bomb.

This threat’s been handed off to terrorists and “rogue” nations. One nuclear detonation wouldn’t end the world, but for hopeful crazies of all stripes it might kick-start the process. And plain old terror would be pure gravy for those nuts.

Atomic weapons are probably the most dangerous and scintillating game-changing achievement of our species. Our scientific brilliance harnessed to produce weapons that would burn millions.

Nuclear weapons are still the 800-megaton gorilla in the room. There are still thousands of them, and who can guarantee there won’t be another Hitler or Stalin?

If, for some reason, a Cold War begins again, this time around I won’t find the process so interesting.

As an 8-year-old with a crew cut, I secretly, deep inside, knew that I would survive. I would be one of those left to pick through the rubble for the interesting bits and start a new world. Maybe wear leather, get a motorcycle.

Now, given the same strategic circumstances and years to ponder the real-world things I’ve read about the effects of nuclear detonations, I don’t think I would survive. I hold no hope in that regard.

Given the slim chance of survival, I recall the phrase grimly and regularly used during the apocalyptic era: After a nuclear war, the living will envy the dead.

While I don’t think I’ll live through such an event, I do hope that someday, somehow, the threat will be gone.

Such hope, irrational as it may seem, magnified enough by enough people, might get us through to a more rational, reasonable world.

E-mail:

Style, Pages 27 on 12/07/2010