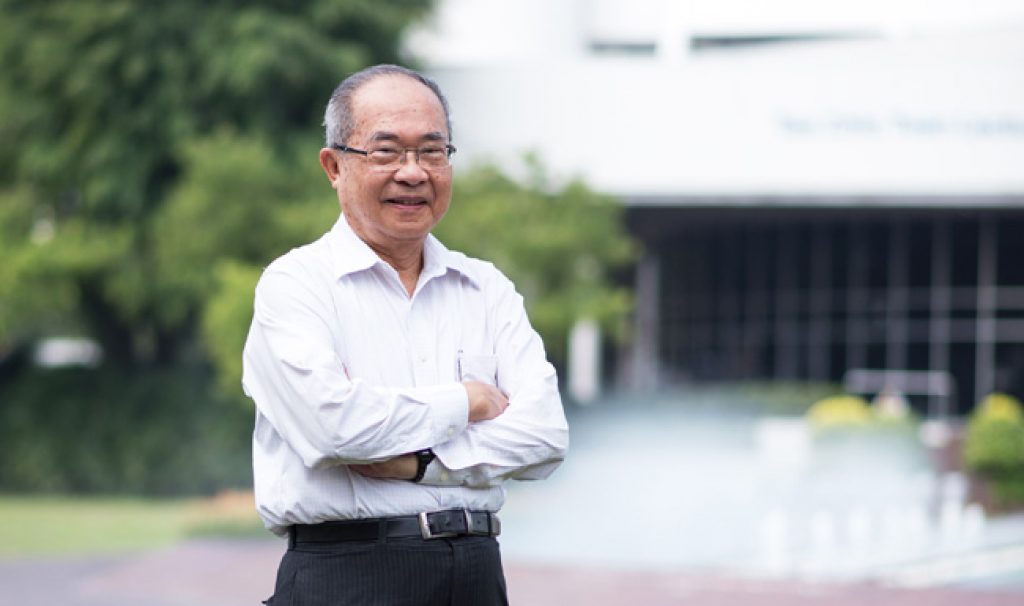

AsianScientist (Oct. 14, 2015) – In his book on the evolution of Nanyang Technological University (NTU), Cham Tao Soon, professor of fluid mechanics and its founding president, explains the relative youth of the administrators and leaders involved: “It was a different age, and many things were started by young men.”

Again and again in the Singapore story this comes up, and it is nearly always young men in their twenties, thirties and forties who are the key players in the tale—men whose wives gave up thriving careers to support their husbands’ endeavours, men who loved and provided for their children but saw them rarely, men who sacrificed lucrative job offers and personal dreams for duty, for country, for the things they built from scratch.

It was indeed a different age: in 1981 Singapore’s population was less than 2.5m (more than 5m today), its gross domestic product per person only US$5,000 (more than US$50,000 today). The then 41-year-old Professor Cham was tasked with training engineers for the nation’s future.

A sweaty, unglamorous job

The new president had nearly become a musician. As a child he had taught himself several instruments, including the piano and violin, and as an upper secondary student at Raffles Institution, he had told his father he wanted to study music.

His father, a court interpreter and film censor for the Ministry of Culture, discouraged him, saying it would be difficult to make a living. Instead, he urged his son to take up engineering—seen as a sweaty, unglamorous profession by most.

“Either you worked in the sun as a builder or you tinkered with your car engine,” Professor Cham recalls.

But it was a secure living, his father insisted; engineers created wealth and comfort, improving people’s quality of life by building material things.

So off Professor Cham went, on a government scholarship, first to the University of Malaya in Kuala Lumpur (as the Singapore campus had no engineering school at the time); then to the University of Cambridge for a doctorate in fluid mechanics. When he returned to serve his bond, it was as a pioneer member of the University of Singapore’s engineering faculty.

“I remember when the faculty of engineering started,” he says. “April 1st, 1969. Everybody thought it was an April Fool’s joke.”

The main task of the 13 pioneer faculty members was to train some 120 undergraduate engineers a year for the massive infrastructure projects that marked Singapore’s early years—housing; roads; and drainage to help prevent the floods that tormented neighbourhoods in the monsoon season. In 1974, weeks before the start of the term, the Ministry of Trade and Industry rang with a request: please double your enrollment to 240 students. On the list of national priorities, research was rock bottom.

Professor Cham kept busy by consulting for Singapore’s rapidly growing industrial sector. For instance, he designed a water-based cooling system for a printing firm that took advantage of air-conditioner discharge. He also literally helped build the university, by designing some of its airconditioning systems.

In 1975, restless, he wanted to leave the university to start an engineering firm with a friend. “But we already allow you to do consulting,” Regina Kwa, the deputy vice-chancellor, retorted. Professor Cham took the hint and stayed.

An engineer’s university

By 1981, Professor Cham had been dean of the engineering faculty for three years.

Then came word from higher up. To address Singapore’s persistent shortage of engineers, the government had decided to open a new school: the Nanyang Technological Institute (NTI). Together, the National University of Singapore (NUS) and NTI would train 1,200 engineers a year to feed the burgeoning building, electronics, petrochemical, and other industries, which Singapore aimed to modernise with technology-intensive activities such as R&D, engineering design and computer software services.

The new institute was something of a political hot potato. The Chinese-medium Nanyang University was a hallowed institution among overseas Chinese, whose alumni ranged from Singapore to Vancouver. When the University of Singapore merged with the original Nanyang University to form NUS in 1980, it rankled the alumni that the government had simply done away with their alma mater at the stroke of a pen.

In that sense, NTI was partly a political project to appease this large Chinese-educated constituency. NTI later became the full-fledged Nanyang Technological University (NTU) in 1991.

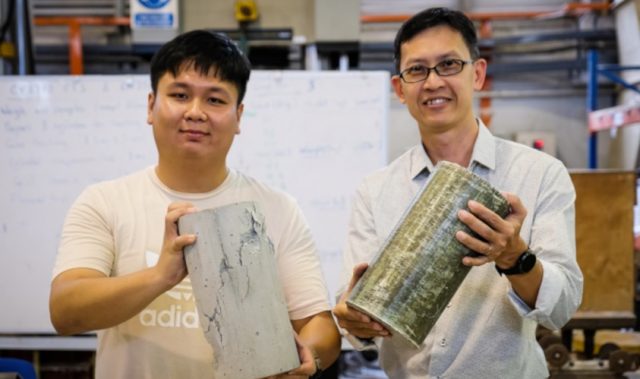

From the start it was Professor Cham who supplied the vision for modernising engineering education. He desired an engineering school with a difference. Unconvinced by what he saw as engineering’s excessive emphasis on academia and theory, he recruited lecturers with extensive industry experience, such as Brian Lee, an electrical and electronic engineer, who had spent more than a decade at General Electric, and Bengt Broms, a soil foundation engineer, who had earlier worked for Shell, and on geotechnical projects in Sweden.

Like medical students, the new engineering students would shadow and learn from the professionals. They helped build and design parts of their own school, such as several thin-shell concrete roof structures, during a second-year training stint. And, uniquely for Singapore at the time, they did compulsory six-month internships in their third year.

“The companies welcomed it,” Professor Cham says. “There were more places on offer than we had students! Why? In the usual two- to three month internship, by the time they know the work, it’s time for them to leave. In six months, they can learn a meaningful job.”

As for building the university itself, the sturdy, bespectacled Professor Cham would roll up his sleeves and sweat through a plate of fish-head curry at a Jurong kopitiam (traditional coffee shop) each week with his colleagues. The tableful of men in button-down shirts would eat and talk through decisions informally before going back to the office and signing off on them. In all, the university’s initial development budget was a generous S$170m. As a political project which had to succeed, it did not want for funds, he says.

Physically, NTU is a school evidently designed by engineers. Visitors are often bemused by its floor numbering system, in which all the levels marked 1 are at the same altitude across campus, all those marked B1 at the same level, and so on down.

“For a large and undulating campus this was deemed to be the most sensible way to determine the altitude with respect to outside roads,” Professor Cham says.

Buildings and hostels, too, were numbered—N1, N1.1, S1, Hall 4, and so on—temporarily, in the hope of raising funds with naming rights. Alas, there have been no takers.

The 107-hectare campus, in the far reaches of Jurong, was in the middle of a jungle.

“There were still squatters, feral dogs, and it was heavily overgrown,” Professor Cham says.

One morning, he arrived in the office to find a snake in his dustbin. Meanwhile, the staff operated out of an old auditorium which some were convinced was haunted.

All this took Professor Cham away from his family. When work started on the institute, he and his wife Ee Lin—a geophysicist he had met in secondary school when they attended the same music competitions—decided she would give up her job so someone could be home with their children.

Today Gee Len, his daughter, is a project manager, while Tat Jen, his son, is a computer engineering associate professor at NTU.

“It was a very easy decision as our philosophy is family above career. Even for me if I have a family appointment which clashes with a business appointment, the former prevails,” he says.

Professor Cham also says he turned down a lucrative job offer when he was tapped to run NTI.

“At the time, my income was about $200,000,” he says. “This was in the 80s, so that was quite a lot, but I was offered a million dollars a year to run a company.”

Good thing he stayed. Within four years, before its first students had even graduated, NTI was named one of the best engineering institutions in the world by the Commonwealth Engineers Council, the Commonwealth’s professional engineering body.

A melodious retirement

Professor Cham remained president of NTU till 2002. Over the years, he has also found the time for many corporate, non-profit and educational board positions.

After starting up NTI, he joined the board of Keppel Shipyard. He has also held directorships at firms such as NatSteel, Singapore Press Holdings and United Overseas Bank. The music-lover at one time also chaired the Singapore Symphony Orchestra’s board of directors.

“I’m down to just two listed companies now,” he laughs.

Last year, he retired as chancellor of SIM University (UniSIM; formerly Singapore Institute of Management, SIM) as well. Today, he remains special advisor to the SIM governing council and senior advisor to the president at NTU.

How does he juggle all these commitments? He plucks out a small diary from a shirt pocket.

“By November, I’ve already got all my meetings planned for the following year,” he says.

That includes family functions and regular SSO concerts, such as a performance by renowned pianist Krystian Zimerman.

Ask if he would have done anything differently, and he claims he has no regrets, aside from wishing he were less impatient and more compassionate.

“I always try my best and if it doesn’t succeed, too bad. I sleep very well at night,” he says.

This feature is part of a series of 25 profiles, first published as Singapore’s Scientific Pioneers. Click here to read the rest of the articles in this series.

———

Copyright: Asian Scientist Magazine; Photo: Cyril Ng.

Disclaimer: This article does not necessarily reflect the views of AsianScientist or its staff.