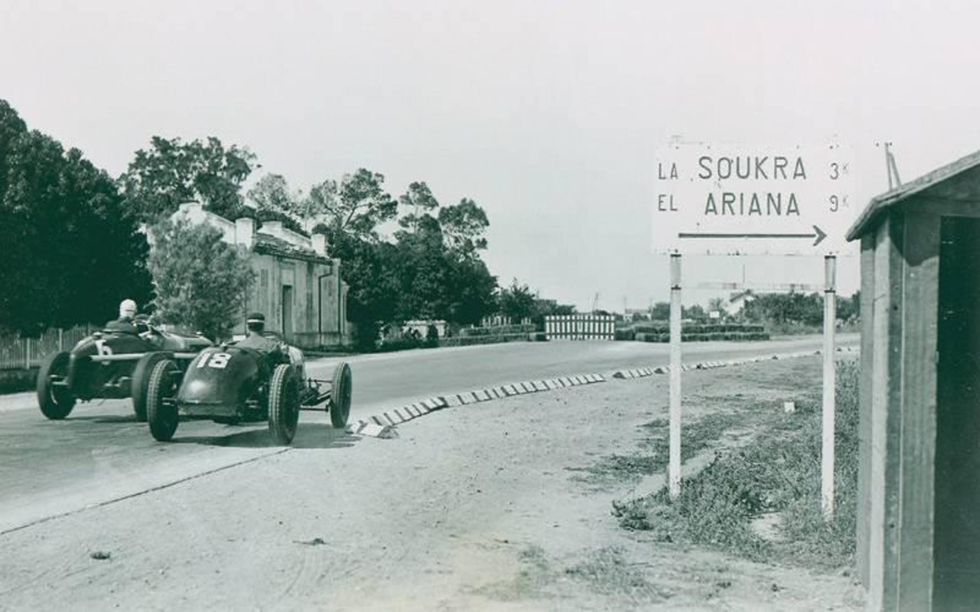

European race cars speeding through what had once been the history-rich ancient city of Carthage on the northern coast of Africa created terrific Depression-era automotive theater.

When this Carthage route (now the suburbs of the modern city of Tunis) was first used for racing in 1928, it was run almost entirely with French cars, notably Bugattis. Tunisia had been a French protectorate since 1880 and wouldn’t gain its independence until 1956. The winning average speed in 1928, in a Bugatti 35C, was nearly 76 mph. By 1932, a Bugatti Type 51driven by Italian star Achille Varzi averaged 90.23 mph. That year, Italian Alfa-Romeos and Maseratis became Bugatti’s major competition, and Tazio Nuvolari won the 1933 event for Alfa-Romeo. The race skipped a year and resumed in 1935.

Motor racing had been competitive among European nations until 1933, when the new Nazi German government began subsidizing its factories. The following year, race cars from Auto Union and Mercedes- Benz began to overwhelm their rivals, and nationalistic issues intensified in the run up to the Grand Prix of Tunisia, which, after April’s race in Monaco, was the first event of the 1935 season entered by the major contenders.

The race was expected to highlight three unconventional cars. One was Auto Union’s Type B, a striking-looking 16-cylinder rennwagen (racing car) that placed the driver ahead of the engine. It was a development of the Type A originally designed for the 1934 season by Ferdinand Porsche, who referred to his creation as the P-wagen. The others were Italian and French responses to the rising dominance of the Germans.

Alfa-Romeo and Enzo Ferrari’s Scuderia Ferrari racing team developed an extraordinary vehicle, christened the Bimotore, powered by two straight-eight engines. Often called the first Ferrari, with its 540 hp, it promised to trounce everyone, including the 375-hp P-wagen. But problems with the Bimotore’s tires canceled its Tunisian run, so Nuvolari (newly reunited with Ferrari at the urging of Prime Minister Benito Mussolini) and Gianfranco Comotti were in their aging P3 Tipo B racers. The third car, called the SEFAC, was a supercharged eight-cylinder design developed by the French government; it proved uncompetitive and failed to qualify.

The 1935 Carthage route—312 miles, or 40 laps of 7.8 miles each—was modified to include straightened sections in front of grandstands to maximize speeds. The event was run to Formula Libre rules rather than the 750-kilogram formula of that era, and the course would highlight the abilities of the most powerful cars.

Private entries by now were mostly put in the shade by factory-backed teams. Between the private sportsmen and the factory entries were rising professional teams with multiple entries, such as Scuderia Ferrari with its Alfa-Romeos and Ecurie Braillard’s Maseratis.

Jean-Pierre Wimille’s Type 59 Bugatti was favored by the French-biased crowd. His car propelled by a 3278-cc, 240-hp, supercharged straight-eight engine, Wimille sat on the outside of the front row, having qualified third. A strong contingent of Italian fans might have favored Varzi, who’d won the pole position with a time of 4:24.8, or Nuvolari, who sat in the middle of the front row.

The Grand Prix began at 2 p.m. on May 5, 1935. Descriptions of the weather vary. One British report emphasized the heat; a French newspaper used the words “un temps magnifique.” Whichever, the atmosphere seemed more commercial than colonial, with the large checkered flag signaling the start and finish, raised and lowered by a fellow in a business suit. Spectators wearing jackets and ties concentrated in covered grandstands adorned with billboard-style advertisements stretched across their tops. Down front, dignitaries sat in a short row of gilt and tapestry-covered armchairs. The Bey of Tunis, wearing a big tasseled cap and pince-nez glasses, vied to be the center of attention next to the French resident general in a military uniform. A stone wall about four feet high between the track and the grandstand was crowded with standing spectators; those in the low grandstand had to stand to see over them.

Mercedes-Benz driving legend Rudolph Caracciola was among these spectators. Mercedes-Benz had not entered the Tunis GP, focusing instead on preparing its W25s for the next scheduled race, another Formula Libre event a week later in Tripoli.

So it was up to Auto Union to represent the Third Reich, but there was tension within the team. Varzi had insisted on being paid in Italian lire rather than German marks, and the subsequent negotiations—along with learning that the new 1935 car wasn’t ready, but Varzi had gotten an upgraded ’34 model—had put teammate Hans Stuck’s nose out of joint. He didn’t race in Tunis, so there was only one German car at the start. That would be enough.

Varzi took the lead quickly and kept it—exactly as he had done in 1932 for Bugatti. Nuvolari ran second, but only for five laps before the car broke. At one point, the P-wagen set the all-time course record with a lap averaging 105 mph. The blistering pace led to a number of mechanical problems. Engines blew up from the strain. Tires failed. Strong, dust-filled winds threatened the P-wagen’s stability. By the middle of the race, the cumulative mechanical culling put examples of four makes of race cars in a lead group. They moved with a “rythme splendide,” reported Parisian newspaper Le Journal.

Varzi’s P-wagen, Philippe Etancelin’s Maserati 6C-34 and Raymond Sommer’s Alfa-Romeo Type B all must have looked in better shape than Wimille’s Bugatti, which had lost its hood. Sommer’s Alfa threw a rod; then the Maserati lost all but top gear. Wimille’s Bugatti hung on but never threatened the P-wagen. Varzi’s win—averaging 101.2 mph for the run of three hours and six minutes—was his third Tunisian GP victory and his first as an Auto Union driver. Wimille came in second, almost four minutes (less than a lap) behind. Etancelin finished third, two laps down. Only eight of the 22 starters finished. More important, the results finally unraveled this Grand Prix’s function as a showcase of French race cars.

Caracciola won in Tripoli and then went on to win the 1935 European Championship for Mercedes by claiming three of the five events in a newly created series instigated by the Germans (the French GP opted out).

The 1936 Tunis race was run with only 12 cars and shortened to 30 laps—yet it became a lively contest between two 380-hp Mercedes-Benz W25Ks and a trio of improved Auto Union V16s, five Alfa-Romeos, a Maserati and a Bugatti. Caracciola won for Mercedes, while accidents ruined the Auto Unions. Varzi was leading and doing 180 mph when the wind disrupted the car, and it tumbled spectacularly. He walked away.

After that display, the 1937 format changed from Formula Libre to sports cars, allowing French machines again to dominate. That was the last Grand Prix of Tunisia until 1955, and with the French gone in ’56, so, too, was the backing for a race in Tunisia.

Since 2000, the city has hosted an annual historic event each October to celebrate its racing heritage.