Walker Evans: Documenting the Great Depression

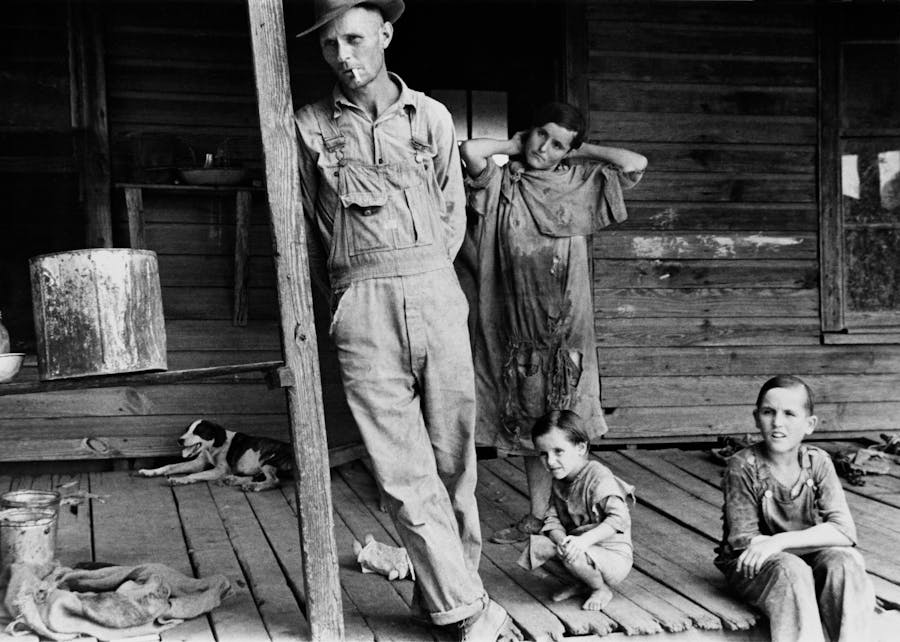

Walker Evan's vernacular style and interest in rural communities and urban individuals made him one of the most influential photographers of the 20th century.

Walker Evans is one of the most influential photographers of the 20th century. World-famous for his black and white prints that documented the impact of the Great Depression, his work has inspired several generations of artists, from Helen Levitt (1913-2009) and Robert Frank (1924-2019) to Diane Arbus (1923-1971), Lee Friedlander (b. 1934), and Bernd and Hilla Becher (1931-2007, 1934-2015). Between an artist and a reporter, Evans threw out conventions and captured the trivial with both beauty and realism. Evans spent his lifetime capturing people found in roadside stalls, modest cafes, frugal rooms and the streets of small American towns. For fifty years, from the late 1920s to the early 1970s, Evans documented the history of the United States in an encyclopedic fashion.

Related: Robert Capa: Photographs From the Front

Early life

Born in 1903 in St. Louis, Missouri, Evans developed artistic tendencies since childhood, beginning with painting and later collecting postcards. He first took up photography thanks to a small Kodak camera with which he photographed his family. After a year at Williams College, he moved to New York, where he worked for the public library. It was there that he devoured the works of TS Eliot (1888-1965), DH Lawrence (1885-1930), James Joyce (1882-1941) and E.E. Cummings (1894-1962), as well as Charles Baudelaire (1821-1867) and Gustave Flaubert (1821-1880). In 1927, after a year spent in Paris polishing his French and writing short stories and essays, Evans returned to New York with the intention of becoming a writer. As a supporting act to his realist essays, Evans began photographing again.

Related: Sally Mann: One of Today's Most Remarkable Photographers

The birth of a method

Many of Evans' early photographs revealed the influence of European modernism, particularly in their formalism and emphasis on dynamic graphic structures. But Evans gradually moved away from this highly aestheticized style to develop his own evocative but more reticent notions of realism. He focused on the role of the viewer and the poetic resonance of ordinary subjects.

He began his career as a photographer thanks to a mission entrusted to him by the United States Department of the Interior. Evans was to photograph a community of miners relocated by the government to West Virginia. Under the direction of Roy Stryker, RA/FSA photographers (Dorothea Lange, Arthur Rothstein, and Russell Lee, among others) were commissioned to document federal government efforts to improve the life of rural communities in small town America during the Great Depression. Evans, however, cared little for the agenda set by his commissioners and adopted a completely personal style. It was at this time that the vernacular style of the artist was born.

Related: Julia Margaret Cameron: The Visionary Victorian Photographer

Let Us Now Praise Famous Men (1941)

In the summer of 1936, Evans interrupted his mission to follow his writer friend James Agee (1909-1955) to the southern United States. Agee was in charge of writing an article on sharecroppers for Fortune Magazine. Evans was to be the photographer. Although the magazine ultimately rejected Agee's lengthy text about three families in Alabama, what emerged over time from the collaboration was Let Us Now Praise Famous Men (1941), a lyrical journey between pictures and poems that immortalized the tragedy of the Great Depression. For many, this work marked the pinnacle of Evans' career in photography.

Want more articles like this delivered straight to your inbox? Subscribe to our free newsletter!

Later work

His success granted him an exhibition at MoMA in 1938, after which the book American Photographers was published by the museum. Between 1938 and 1941, he produced a sublime series of portraits taken in the subway. Hiding the camera under his coat, Evans captured the authentic expression of his traveling companions. These portraits remained unpublished for 25 years, until 1966, when the publishing house Houghton Mifflin launched Many Are Called, a book of 89 photographs, with an introduction by James Agee written in 1940.

Between 1934 and 1965, Evans contributed more than 400 photographs to 45 articles published in Fortune Magazine, of which he became the official photographer from 1945, and then the special editor for photography in 1948.

The last part of his career was occupied by snapshots taken with a Polaroid SX-70. The unique SX-70 prints are the culmination of half a century of photographic work, which has marked the history of photography forever. Evans died in Connecticut in 1975.