Sarin gas blamed for Gulf War syndrome

- Published

US scientists say they have discovered what caused thousands of soldiers who served in the 1991 Gulf War to fall sick with mysterious symptoms.

They have pinned the blame on the nerve agent sarin, which was released into the air when caches of Iraqi chemical weapons were bombed.

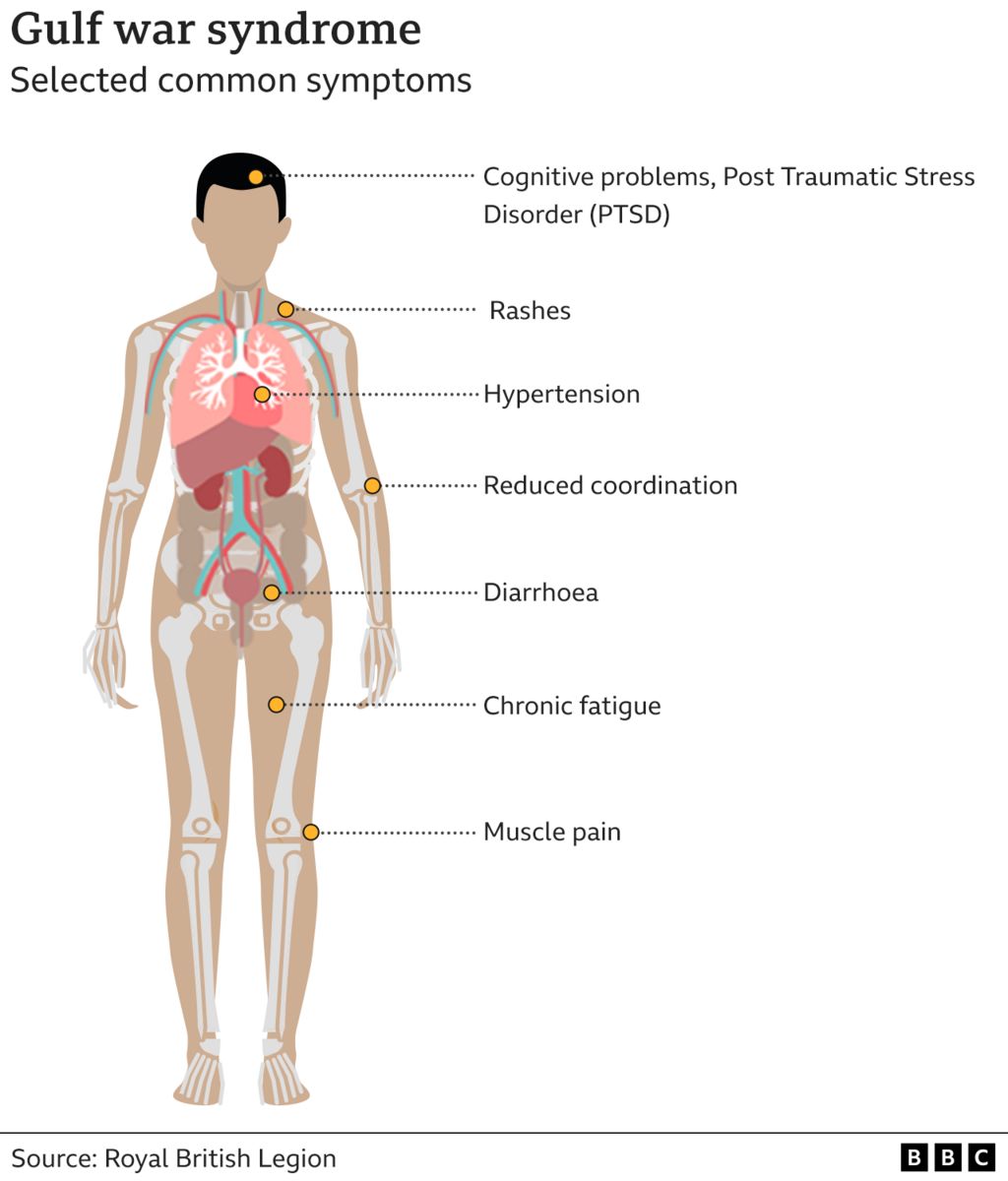

Many veterans have complained of a range of debilitating symptoms which developed after their service.

But for decades the cause of Gulf War Syndrome has remained elusive.

Sarin is usually deadly, but lead researcher Dr Robert Haley said the gas that soldiers were exposed to in Iraq was diluted, and so not fatal.

"But it was enough to make people ill if they were genetically predisposed to illness from it."

Dr Haley said the key to whether somebody fell ill was a gene known as PON1, which plays an important role in breaking down toxic chemicals in the body.

His team found veterans with a less effective version of the PON1 gene were more likely to become sick.

The latest study - largely funded by the US government - involved more than 1,000 randomly-selected American Gulf War veterans.

Dr Haley, of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, said: "This is the most definitive study.

"We believe it will stand up to any criticism. And we hope our findings will lead to treatment that will relieve some of the symptoms."

Many British cases

More than 50,000 British troops served in the war which followed Iraqi President Saddam Hussein's invasion of Kuwait.

The Royal British Legion said research suggests up to 33,000 UK Gulf War veterans could be living with the syndrome, with 1,300 claiming a war pension for conditions connected to their service in the Gulf.

Over the past three decades, the veterans say they have struggled to have their illness taken seriously.

Before the war, Kerry Fuller from Dudley, West Midlands, was a fit 26-year old who loved climbing and went to the gym several times a week. Now it's a daily battle simply to get out of bed.

At the age of 40, he had a stroke. Now 58, he says he has such excruciating muscle and joint pain that he screams so loudly when he moves in the night that he wakes his whole household. He suffers from problems with his balance, memory and speech.

"Even when I was still in the military, I was getting illness after illness, breathing problems, chronic fatigue," he said.

"And when I questioned whether it could be anything to do with my service in the Gulf or what we were exposed to, the military line was 'You're talking nonsense, there's no evidence. Two paracetamol. Crack on'."

No positive answers

The National Gulf Veterans and Families Association, a charity working with British ex-soldiers who are ill, welcomed the study.

"For 30 years they have been disowned, ignored and lied to by consecutive governments, with no positive answers to their questions about exposure to toxic substances and gases and the affect it had on them both physically and mentally," it said in a statement.

"We hope the UK government takes this report on board and will respond by offering Gulf veterans access/opportunity to have the tests.

"This will hopefully lead to more meaningful and proper medical treatment which they have for too long been denied."

The Ministry of Defence said: "We continue to monitor and welcome any new research that is published around the world and financial support is available to veterans whose illness is due to service through the MoD War Pensions and the Armed Forces occupational pension schemes."

But the Royal British Legion said there had been "little meaningful research" on Gulf War Syndrome in the UK.

Professor Randall Parrish, of the University of Portsmouth, published a study last year which ruled out depleted uranium as a cause.

He said: "I think this is a great example of an issue that has required a long-term effort to solve, but which only a few scientists have persisted in - others giving up and assuming it is either not a real illness or too complex to solve, and funding agencies not wanting to wade too deeply in the politics of it."