The Man Who Clothes Asia: Uniqlo Chief Tadashi Yanai

(Nikkei Asia) — Tadashi Yanai turns up to the interview in his Uniqlo mask and a cardigan over a button-down shirt, striding into his Tokyo office meeting room. The wall is decorated with an intricate world map and a framed piece of Japanese calligraphy that reads: “world’s number one.”

Ranked as Japan’s richest man by Forbes, Yanai could probably afford more expensive clothes than those he is wearing. But he has made his fortune as an evangelist for casual wear. Today, it is almost impossible to find anyone in his native country who has never shopped in Uniqlo.

“Casual wear can be worn anytime, anywhere, by anyone, freely,” he wrote in his 2003 autobiography. “If we could sell mass volumes of casual clothing for both men and women, that would be a huge success.” This has been his mantra since the 1980s, when he was opening his fourth Uniqlo shop.

That was more than 2,200 stores ago. Since then, his Uniqlo brand has harnessed the power of global production chains and an uncannily prescient eye on consumer trends to emerge from the global financial crisis as the world’s third-largest clothing retailer.

Recently, Yanai, the 71-year-old chairman and chief executive of Fast Retailing, Uniqlo’s parent, is sounding ever more confident that the zeitgeist has caught up with his original vision. In a press conference last year, Yanai declared that the age where people bought clothes to fulfill their material desires has ended.

“Gone is the era when people strove wholeheartedly to enrich their material lives,” he said. Unlike earlier times when people dressed to impress others, he said, people now want clothes that allow them to live “a high-quality lifestyle.”

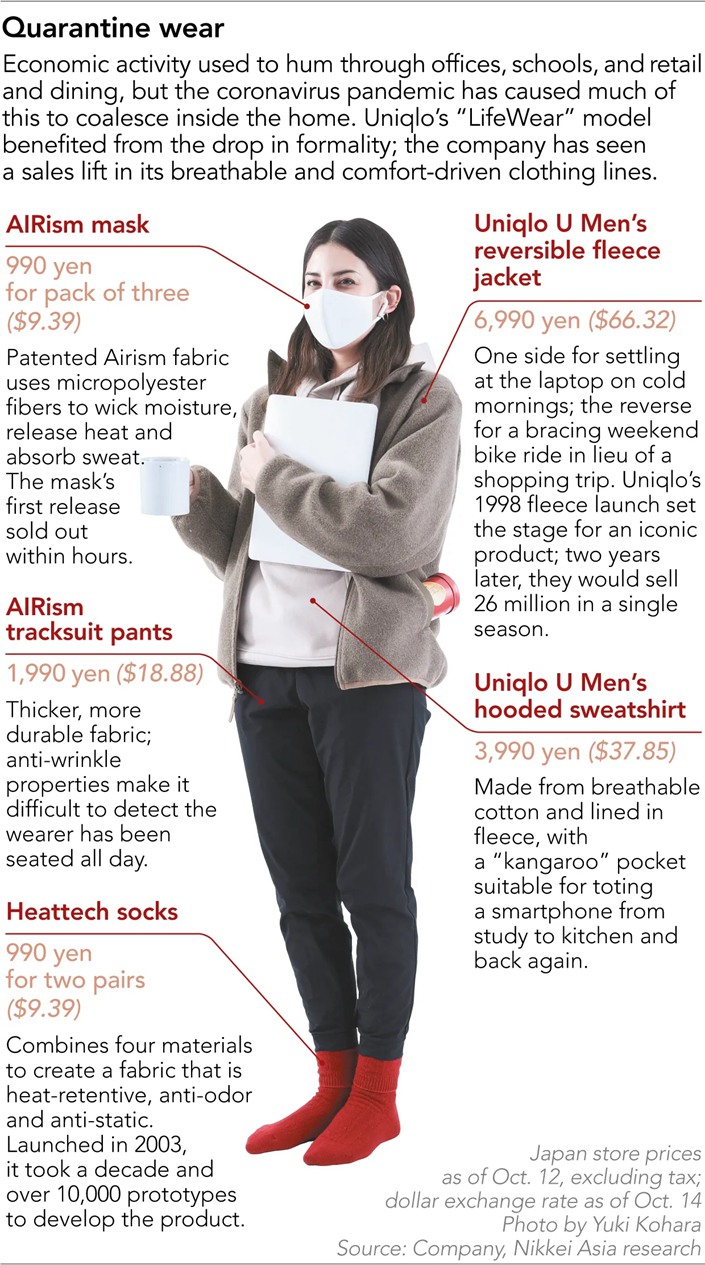

At Uniqlo, philosophy and clothes effortlessly intermingle. “LifeWear” — the word coined by Uniqlo for its products — “is the ultimate everyday clothing,” Yanai said last year, promising that it would continue to adapt and evolve by “deeply considering every aspect of everyday life needs.”

Eerily ahead of fashion trends, the company’s LifeWear has turned out to be uniquely suitable for this year’s pandemic: breathable masks, quarantine-friendly sweatpants, cuddly Zoom-call-chic jersey T-shirts. The company is marketing “working from home” product lines on its websites and advertisements.

“[Coronavirus] is a big crisis for companies all over the world, but it is also a big chance,” he told Nikkei Asia. “Successful companies always emerge out of a crisis.”

The AIRism masks, for example, are some of the most successful and recognizable symbols of Uniqlo’s branding genius. Despite the fact that, for months, Yanai was dead-set against them — “We will contribute [to the fight against the coronavirus] through clothing, rather than masks,” he originally said — overwhelming demand has quickly made them a staple product of LifeWear.

A massive hit as soon as they debuted in June in Japan, the masks also played a role in attracting customers back to Uniqlo’s physical stores. Many queued for hours to buy them.

“Coronavirus is the center of the [consumer’s] interest,” said Yanai, eventually. “Safety measures are the best way to attract customers.”

Covid-19 has not been kind to clothing retailers: Brooks Brothers, J-Crew and J.C. Penney are among the dozens or even hundreds of businesses that have declared bankruptcy.

After the Covid-19 outbreak this year, Fast Retailing was forced to close its stores worldwide, suffering a nearly 40% drop in sales in the March-May quarter. The company’s sales in the fiscal year ended August are forecast to total 1.9 trillion yen ($17.9 billion), a 13% drop from the previous year.

But Uniqlo has been saved by its customers, who have tenaciously continued to shop, despite the risks. “I bought a lot of Uniqlo and [its sister brand] GU clothing this year,” including multiple comfortable dresses for lounging at home, said 27-year-old Akari Ono, shopping at one of Uniqlo’s newest flagship stores in Harajuku, a trendy district of Tokyo, which opened in June. The brands “are reasonably priced, and they are useful especially since I haven’t gone out as much this year,” she said.

Despite the star-crossed opening date, the sleek Harajuku store has done fairly well, with several shoppers milling around trying on clothes one day in October. One woman who had traveled into Tokyo from the neighboring Saitama Prefecture said that, despite buying fewer clothes after the coronavirus outbreak, she has still been spending on Uniqlo for her family — T-shirts, pajamas, padded Bra Tops and technical Heattech items. “As a family, Uniqlo is the brand we use the most,” her 12-year-old daughter added.

|

Overall, the numbers have been surprising. In June, Japan same-store sales, including e-commerce, grew by 26% year on year. Monthly sales have increased through September, which showed growth of 10%.

Yanai says he still believes in physical stores, despite the bruising experience of this year. “E-commerce is a virtual world, which is an imitation of the real world,” said Yanai. “There is nothing that tops the original.”

But he sees room to blend the two models. “Physical stores that serve customers well would still grow,” he said. “That is the same for virtual [online] stores.”

As the pandemic continues to run its course, technology is ever more embedded in people’s lives as they work, rest, and socialize seamlessly in both digital and physical spaces. The success of Harajuku is also part of a plan to continue embracing physical stores while blending it with the digital world. At the Harajuku store, there are over 200 displays that show style suggestions and items offered by Uniqlo both in-store and online.

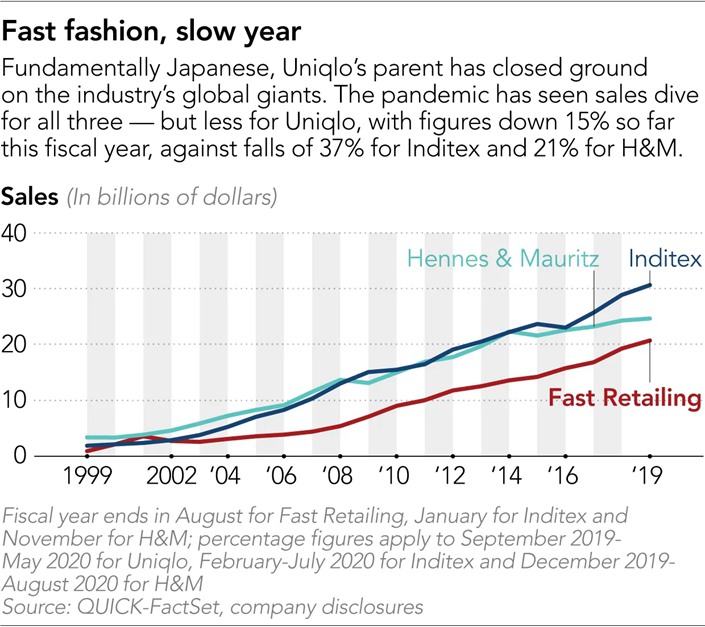

Many fashion brands have been pushed by the pandemic to accelerate their shift to digitization and shut down bricks-and-mortar stores, including Fast Retailing’s global competitors, Zara parent Inditex and Sweden’s Hennes & Mauritz.

Inditex’s quarterly sales declined by up to 44% this year, while H&M’s dropped by up to 50%. Inditex recently announced plans to reduce up to about 700 stores, while H&M also said in October it plans to reduce total store count by about 250 in 2021.

Uniqlo, on the other hand, is yet to announce closures. Its store count has actually risen since mid-2019.

Tinker, tailor

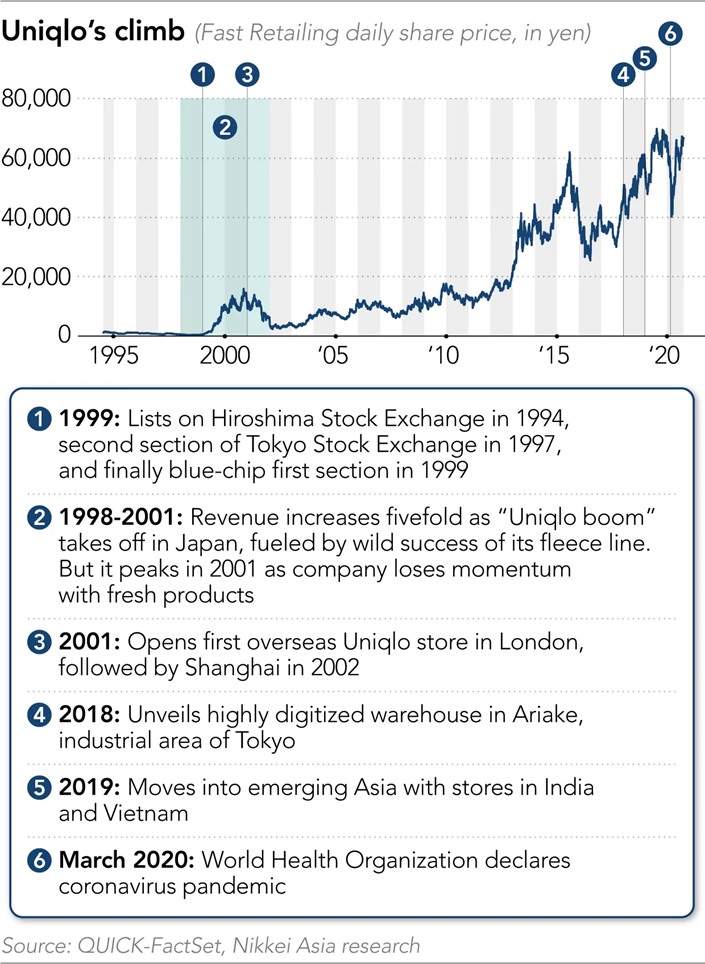

Yanai’s life has never been far from retail. After briefly working as a graduate in the supermarket chain now known as Aeon, in 1972 he moved into the clothing company founded by his father in the rural prefecture of Yamaguchi. He opened his first Uniqlo store in 1984, with its breakthrough moment following in 1998, when the brand opened the first Tokyo outlet in Harajuku. Launched amid Japan’s post-bubble economy, the brand’s opening campaign selling lightweight fleece for 1,900 yen caused a sensation.

Back then, Uniqlo merely represented cheap clothing — the cool factor came much later. But it was enough to see the company’s revenue swell fivefold between 1998 and 2001. For some years it stuttered, before, supported by fresh hit items and an overseas expansion drive, Fast Retailing resumed growth, even through the 2008 global financial crisis.

Since its beginnings, Fast Retailing’s strength has always been to nail reasonable pricing for basic items, said Takahiro Kazahaya, a retail analyst at Credit Suisse Securities. Yanai has “set a clear mission for the company to provide cheaper and more functional clothing for everyone of all ages, and has been doing what it needs to achieve that.”

The secret of Uniqlo’s pricing power is partly due to the large volumes of orders it places with the textile industry. That allows it to work with textile makers more closely, to mass-produce exclusive materials for low prices. “Most apparel makers just tell us to do things at low cost,” a Japanese textile company told Nikkei. “But Yanai-san asks us what we need in order to do things he wants us to do.”

Other partnerships include one with knitting machine maker Shima Seiki Mfg. for a seamless “3D Knit” collection, and it has successfully raised design quality by releasing regular collections with top designers including Christophe Lemaire and Ines de la Fressange.

The company has always been led by Yanai, currently chairman, president and CEO. In the past, Yanai has expressed plans to retire at 65, and again at 70 — but, at 71, he is still going strong. Many wonder where Uniqlo’s relentless drive would go should he step back.

|

In 2013, he said: “It is impossible to resign from being president as we accelerate global expansion.” When he left the board of tech investment giant SoftBank Group at the end of 2019, a company spokesperson said Yanai planned to focus on his job of running Fast Retailing.

Yanai’s unyielding discipline and strongly held principles have also been offputting. Only once, in 2002, did Yanai step down to let Genichi Tamatsuka, a former deputy, take over the role of president.

But three years later, Yanai had returned. Tamatsuka “wanted steady growth, but I want more transformation and growth,” said Yanai at the time. Tamatsuka left the company to eventually become the president of the Japanese convenience store chain Lawson.

Yanai leaving his position would be the “biggest risk” for Fast Retailing, said Kazahaya.

“The balance of quality and pricing has been taken well [by customers], leading to increasing share primarily in Asia. ... That has not changed [with Covid-19],” the analyst Kazahaya suggested. Even as consumers globally become more selective, Fast Retailing “can still grow as one of the winners,” he said.

Uniqlo casts a wide net, targeting customers of all ages and lifestyles, which means the “long-term potential market is bigger for Uniqlo [than Zara],” said Takahiro Saito, CEO of fashion retail consulting firm Demand Works and author of the book “Uniqlo vs. Zara.” Eventually, he said that Uniqlo would be well-placed to become the global No. 1 in terms of revenue, but said it is still well behind Zara in profitability.

Its parent company Inditex generated $31.5 billion in revenue and 4 billion dollars in net profit in the fiscal year ended in January, while Fast Retailing generated $20.7 billion in sales and $1.4 billion in net profit in the fiscal year ended in August 2019, based on Quick-FactSet data.

As more consumers shift to buying online, Uniqlo is disadvantaged compared to Zara in the race to generate profits, Saito pointed out. Uniqlo’s items are cheaper compared to Zara’s trend-following items. E-commerce accounts for 11% of Fast Retailing sales for the fiscal year ending 2019, while it aims to raise the ratio to 30%. For Inditex, which has bigger sales than Fast Retailing, e-commerce accounted for 14% of total sales in fiscal 2019.

Going global

Uniqlo saw phenomenal success in cultivating the loyalty of Japanese customers, but room to grow there is limited. Uniqlo’s home market is saturated and shrinking as its aging population declines. Fast Retailing sees Asia as its growth driver.

Yanai said that mainland China would “soon” top the overall Japan store count of 814, including franchises. Uniqlo has 782 stores on the mainland as of the end of September. The number has already surpassed Japan in terms of directly operated stores, as well as overtaking the store counts of H&M and Zara in China.

China has also long been a major production hub and key market for Fast Retailing. The company first set up a manufacturing base in Shanghai in 1999, before unveiling its first stores in 2002. Among Yanai’s inspirations then were the Hong Kong-based brand Giordano, founded by Jimmy Lai, as well as Western brands such as Next and The GAP.

Operating an Asiawide business can be fraught. Having studied politics and economics as a student, Yanai has a particular view of the world, which, as he puts it, is shifting from a Western-centered one to an Asian one. Japan, and its businesses, cannot afford to take sides. “Japan is in the middle of it,” said Yanai. Japan can be a bridge for both sides, he said, “but in the worst case, [Japan] would be a shield for the U.S. defense.”

|

To navigate the shift, “people who do business have to have historical perspective, or something like a worldview,” said Yanai. “Overseas Chinese still have economic power [in Southeast Asia] — you have to cooperate with them,” he said.

Uniqlo currently has about 60 stores in North America and 100 in Europe. Stores in key cities such as New York, Milan, and Paris have been part of its global branding. While the company had plans by 2013 to open 200 stores in the U.S. by 2020, it is struggling to turn profit in the country and has around 50 so far.

There will be some adjustments to its physical stores as the retailer faces the pandemic, according to Yanai. In Japan, which is Uniqlo’s biggest market, he said about one-third of over 800 stores would be “renewed” in terms of designs or locations.

“One of the big changes in [consumer] lifestyle is that they shop in neighborhoods,” Yanai observed, adding that more shops may move from retail centers to rural residential areas. “Sales and land prices do not correlate,” he explained. City-center stores have been important for attracting tourists, but “inbound tourists in the future may not shop as much as they used to.”

Uniqlo products are not sold on the U.S. Amazon e-commerce platform. “We are close to all of them,” said Yanai, referring to Amazon and also to China’s Alibaba Group. The company uses Amazon services such as for cloud computing, but there is little benefit for Uniqlo in becoming one of the many brands on others’ online malls, he said.

Fast Retailing has staked its reputation on becoming a “new digital consumer retail industry” in recent years, in an ambitious effort to digitize and transform all parts of its supply chain. Those goals “must speed up, with or without the coronavirus,” admitted Yanai.

Since opening an automated warehouse for e-commerce sales in Tokyo’s Ariake district in 2018, it set up a second warehouse in Japan this year. It is also planning to open similar warehouses in other markets.

Uniqlo last year entered Vietnam and India, which is seen as another potential growth driver for the company. As of the end of September, Uniqlo had 251 stores in Southeast Asia, India and Australia. Yanai told Nikkei last year he foresaw Southeast Asia sales eventually reaching the same level as China.

Yanai’s optimism for growth comes in large part from his faith in the growth of Asia’s middle class. “We are going to set up more stores than before,” said Yanai. “Southeast Asia, especially, is a dollar box” that would usually generate high growth rates, despite some slowing down because of Covid-19, said Yanai.

Yanai is also hopeful about Asia for hiring talent. “In India, we hire a lot of graduates, and everyone is so bright,” he said.

While the U.S. and Europe are full of competitors that sell low-priced basic items, emerging markets are still new battlefields with no clear winners. Kensuke Kojima, a fashion retail consultant, also suggested that Uniqlo has an advantage over Zara and H&M in Asia because it is generally designed for Asian body shapes.

Yanai is already thinking about the kind of consumer that will emerge post-pandemic. “The fact that the coronavirus spread so fast is proof that the world is not divided,” said Yanai. Rather than just isolating people, Covid-19 made “people realize that unilateralism, or bilateralism, is not good,” he said. “That would be the new norm.”

“Everyone started thinking about life and death,” he said. As a retail business leader who always needs to be aware of changes in consumers, he said, “that will become reflected in various parts of life.”

This story was first published in Nikkei Asia.

Download our app to receive breaking news alerts and read the news on the go.

- PODCAST

- MOST POPULAR