The Memphis Grizzlies do it by committee. They are the only team in the NBA that didn't have a 20-points-per-game scorer on its roster this season, but nine Grizzlies averaged between 9.1 and the team-high 19.1 posted by Ja Morant. Coach Taylor Jenkins regularly deployed a 10- or even 11-man rotation, and, in their first 30 games, 11 different players led them in scoring.

On Wednesday, Memphis will fight for survival against the San Antonio Spurs (7:30 p.m. ET, ESPN -- stream via fuboTV). The play-in represents a chance for redemption, after falling just short in this scenario last August, without its other cornerstone, Jaren Jackson Jr. Considering that Jackson returned from that knee injury less than a month ago, merely being back here is a monumental achievement.

To pull this off, the Grizzlies played to their strengths. They were one of the least efficient halfcourt teams in the NBA, hampered by poor 3-point shooting, so they played in the halfcourt as little as possible. No team forced more turnovers off bad passes, and no team was better in transition. This is a demanding way to play, made more so by this season's schedule: Memphis had 11 back-to-backs after the All-Star break, to make up for a league-high six postponed games. Without depth, this style might have worn everybody out.

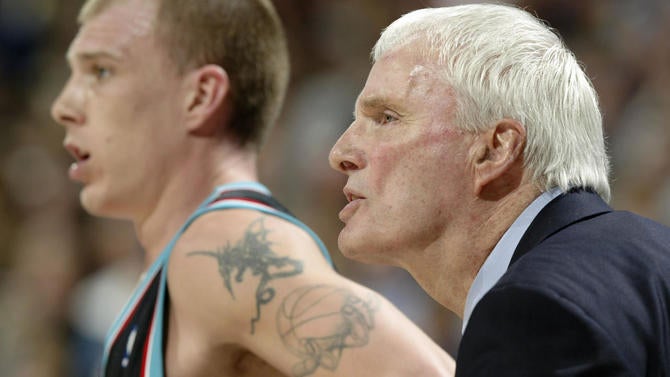

Morant and Jackson are the faces of a new era of Grizzlies basketball, but the team's commitment to harassing playmakers and getting out on the break is a throwback: Hubie Brown's Memphis teams did the same thing the early 2000s. In an interview with CBS Sports, Brown said that there is another benefit to the Grizzlies playing a lot of guys: It gives their horde of young players more opportunities to develop.

"You gotta give them a ton of credit," Brown said. "Their coaching staff has done a wonderful job there, ever since they've taken over. They are developing young talent. The young talent is playing with confidence, in a style of play which is perfect for the talent."

When Brown, now an NBA analyst for ESPN, arrived in Memphis in November 2002, the team had an 0-8 record and no track record of success. The franchise had relocated from Vancouver the previous season and had never won more than 23 games. The Grizzlies, led by second-year big man Pau Gasol, finished that year with 28 wins and a much more respectable point differential, and the next season their goal was to go .500.

It was shocking, then, when the 2003-04 Grizzlies pressed and trapped and substituted their way to 50 wins. No team ran more, and no team forced more turnovers per possession or scored more points off those turnovers. Gasol, their only player who averaged 30 minutes or more, led the team in scoring with a modest 17.5 points per game.

Gasol started at power forward next to Jason Williams, Mike Miller, James Posey and Lorenzen Wright, but often closed games at center. Memphis' all-bench lineup of Earl Watson, Bonzi Wells, Shane Battier, Bo Outlaw and Stromile Swift routinely tore other second units apart, and collectively the Grizzlies started to turn a city full of college basketball fans on to the pro game.

"We could score, we could defend, it was a very exciting team to watch play," Brown said. "The city fell in love with the team. They were not drawing well, but during the season the games became sellouts. Naturally the playoffs were all sold out."

Before Memphis hosted a playoff game for the first time in franchise history, commissioner David Stern presented Brown with the Coach of the Year award. Every fan in the arena had a white "growl towel" with the phrase "BELIEVE IT" in big block letters, above the names of all the players on the roster and Brown. The Grizzlies lost by two points when Mike Miller missed a buzzer-beating 3-pointer -- "the ball went down into the basket and popped out," Brown lamented 17 years later -- en route to a Spurs sweep, but Brown looks back on that time fondly.

"Those two games at home, you couldn't hear yourself think, OK," Brown said. "That's how they were. And every time I come back to do a TV game in that building, I can't believe the people. You ask any one of my guys that came back when they went to other teams and came back in the building. Those people never forgot them."

The Grizzlies are a couple of generations removed from the one defined by Brown's deep bench, but their fans watched them take the league by surprise again last season. This success is not only a product of the franchise striking gold with Morant and Jackson, both selected near the top of the lottery. In the last two years, the front office has nailed a series of draft picks (Brandon Clarke, No. 21, 2019; Desmond Bane, No. 30, 2020; Xavier Tillman, No. 35, 2020), trade acquisitions (De'Anthony Melton, Grayson Allen) and undrafted signings (John Konchar, Killian Tillie).

Even their veterans are young. Dillon Brooks, who embodies Memphis' aggressive approach on defense more than anyone, and Tyus Jones, who keeps the second unit organized, are both 25 years old. Their elder statesmen are Most Improved Player candidate Kyle Anderson, who turns 28 in September, and bruiser Jonas Valanciunas, who turned 29 this month.

Brown likes the balance they have with Valanciunas and Jackson sharing the frontcourt and Morant -- "a point guard who can get to wherever he wants to out of whatever you're running" -- running the show. This is an unselfish team that plays much older than it is, with a strikingly low turnover percentage for an offense predicated on ball movement. Morant's 26.7 percent usage rate is low for a lead ballhandler who is undeniably a star. On per-minute basis, Valanciunas averages more points.

The Grizzlies' 38-34 record, Brown said, "is no indication of their talent." He thinks they could have "easily" finished somewhere in the 40s if not for Jackson's injury. Months after they went 4-4 in the stretch when Morant was sidelined with an ankle injury, it remains somewhat mystifying that they did it. "This is the growth period," he said, and the Grizzlies are ahead of schedule because they already believe they can compete with elite teams.

He is particularly fond of Valanciunas, whom Memphis acquired from the Toronto Raptors two years ago as part of the Marc Gasol trade.

"I love Valanciunas," Brown said. "Every time I would do [Toronto's] playoff games, I used to kid him when I would see him. I said, 'If you played for me in the old days, you'd be averaging 20 points or better.' Because that kid can really score. And you see what they've done with him. They've recreated a whole new career for this kid."

To Brown, Valanciunas' confidence shooting lefty and righty hooks in the post reflects well on the Grizzlies' coaching staff. Brown hasn't called any of their games this season, and he doesn't have a relationship with Jenkins, but he called himself a big fan.

"I've never met him," Brown said. "I don't know him. I've admired him from watching his teams on TV as well as following the box scores."

Valanciunas is also the player most responsible for the Grizzlies finishing fourth in offensive rebounding percentage. With him on the court, they've rebounded 31.2 percent of their misses, which is better than the New Orleans' Pelicans' league-leading mark. This is important for the same reason that forcing turnovers is important.

"When you have a young team, you need more shots," Brown said.

Brown has believed this dating back decades, and the roots of his 10-man rotation go back just as far. "When I broke in, in the 70s, very seldom anybody played more than eight guys," he said. "And it was like tradition. But we went away from that." He won an ABA title this way with the Kentucky Colonels in 1975 and revived the Atlanta Hawks this way after the NBA-ABA merger, pressing for all 48 minutes. It all started, he said, in September 1972, at a small college gym, before his first practice as an assistant coach for the Milwaukee Bucks.

Led by the legendary Kareem Abdul-Jabbar and Oscar Robertson, the Bucks were coming off a 63-win season and had won a title the year before that. At Van Male gymnasium on the campus of what was then called Carroll College, Bucks coach Larry Costello told Brown, his only assistant coach, that each one of them would work one end of the court.

"I'll take care of the first eight guys because we're only going to play eight guys," Costello said, as Brown recalls it. "You gotta take care of players, 9, 10, 11 and 12."

"What do you mean, 'take care of them?'" Brown said.

"Well, all four of 'em were All-Americans, and they're going to be pissed off every day," Costello replied. "You're going to handle them, I'm not handling them. You gotta keep them happy. The only time they play will be in garbage time, but you gotta keep 'em happy and you gotta make sure that they develop."

Costello walked away, leaving Brown standing by himself at halfcourt.

"After I did two years of that great team, and I'm getting my first job, I said, you know what, I will never, ever play eight guys. I'm playing 10 guys because I only want two guys a day to be pissed off at me."