Heading out the door? Read this article on the new Outside+ app available now on iOS devices for members! Download the app.

One person in these pages was a 67-year-old surgeon who died after helping coronavirus patients and contracting the illness himself. Another was a 25-year-old who volunteered to help adaptive climbers in her community. A recent one was an icon in UK and global mountaineering, finally gone at age 90 after generations of rescuing others, followed shortly by a celebrated alpinist who was an important role model for giving back to mountain communities and did so until the end. Yet another young woman, having grown up in Hong Kong with minimal opportunities to be in nature, worked for years to help maintain wild areas and make them accessible to urban youth. The last of 2020 was head of his area climbers’ coalition, an advocate and steward who organized a climber cleanup every year.

This year those herein range in age from 16 to 103.

“Climbers We Lost” is our annual tribute to community members now absent. This compilation, begun in 2012, is hard all around, but a solace, and may be the most important thing we do all year.

As ever, please know that we try but can never cover everyone, and may inadvertently miss people. We encourage you to add names, remembrances and images in the comments field.

We also refer you to this excellent resource, the Climbing Grief Fund, with thanks to the American Alpine Club and to Madaleine Sorkin for leading the effort.

With deepest thanks to all our contributors, and our many condolences to friends and families.

—Alison Osius and Michael Levy

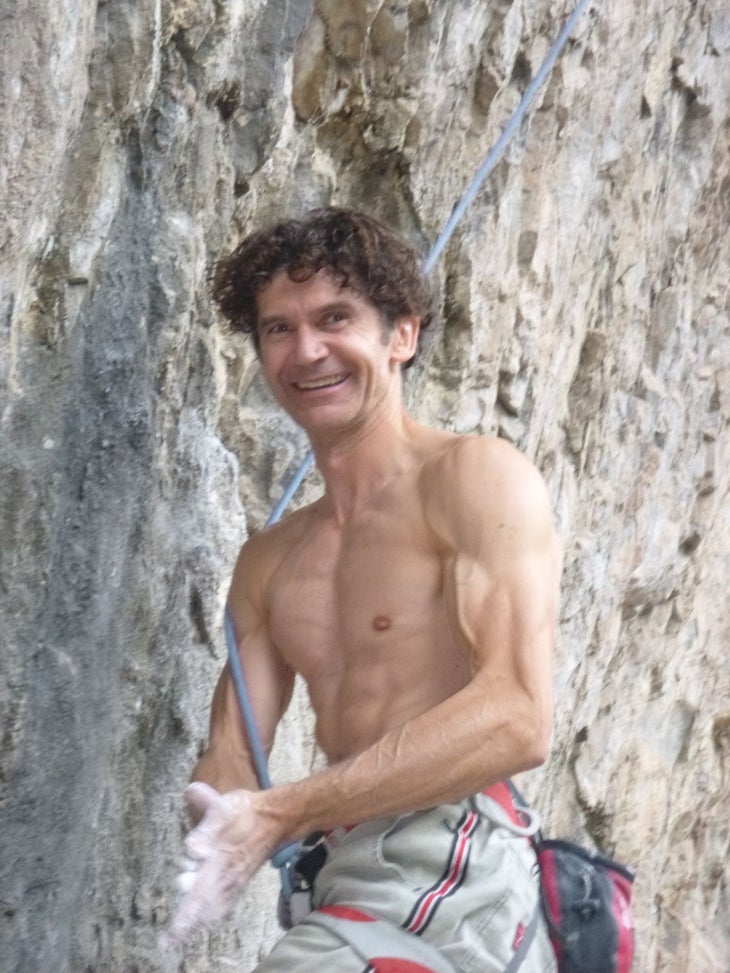

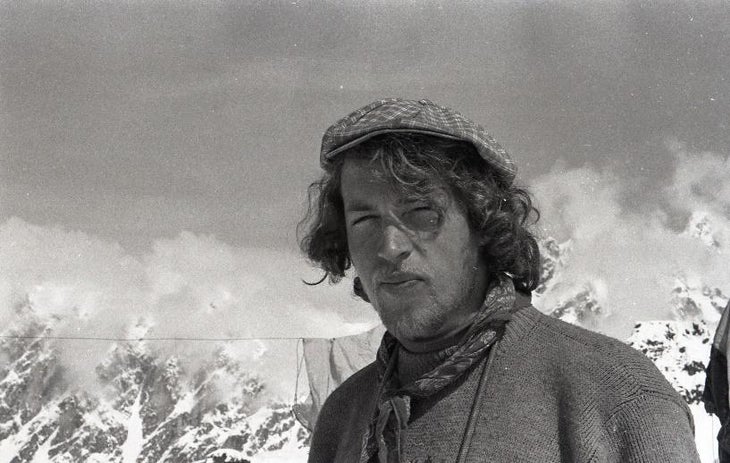

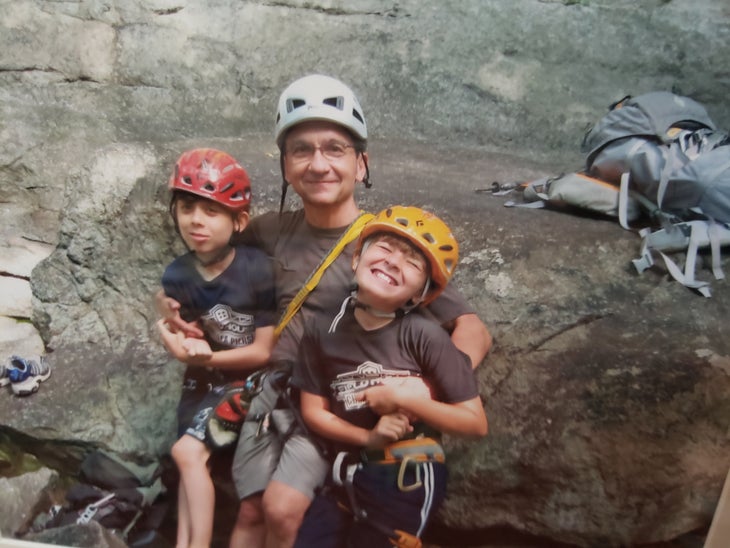

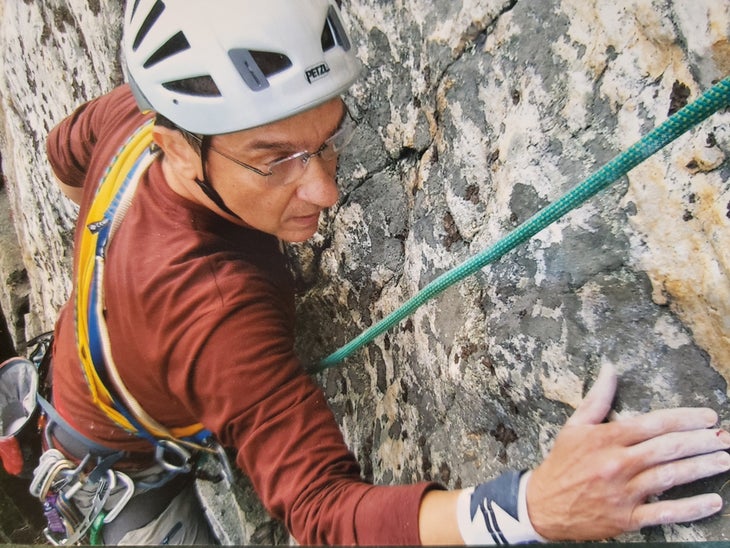

Darek Krol

57, December 26

Grief is an enigma, amorphous, elusive, and in your face all at once. It contains peaks and valleys, twists and turns, crevices and hidden folds where it lies dormant before rearing its head again without warning. Yet if there’s one truth I understand about humans, it’s that we adapt.

Darek Krol was a shining emblem of adaptation, resilience and growth. Immigrating to the United States from Poland in 1997 with his young wife, Anita, and infant daughter, Nina, speaking virtually no English, Darek initially simply wanted to get his family secure and settled in their new home. He took his first job in Boulder washing windows, having passed his interview with mere hand gestures and an abundance of smiling. Darek’s career flourished in a matter of a few short years. He taught himself to program, and that combined with his gift for languages gained him employment developing linguistic translation software for a local Boulder tech startup. Eventually, he gained a senior-level position as an IT director for the Boulder Valley School District. He was smart, adept, and personable, probably the friendliest person you could ever want to be around, let alone employ.

Aside from family, Darek’s passions consisted of climbing, skiing, climbing, fine wines, climbing, astronomy, climbing, and cuisine, but mostly climbing.

Darek discovered rock climbing 40 years ago, at the age of 17, in Poland, where he quickly made his way through the grades and forged lasting friendships across Europe. He was an organizer and innovator from the start: co-creating and editing two climbing periodicals, one of which is still in print; helping launch the Korona Rock Gym, in Kraków, which is still operating; and organizing regional and national climbing competitions.

By the late 1990s, with Darek by now firmly planted in Boulder, the steep limestone walls of Rifle Mountain Park became a frequent destination and eventual obsession. The 360-mile round-trip commute from home was a weekly routine for at least six months out of every year for nearly two decades. Darek drove as fiercely as he climbed. To ride in the passenger seat of his turbo Saab always felt like witnessing a well-rehearsed redpoint attempt: banking, shifting, braking and accelerating at the precise moments as if in harmony with the route we were taking. While it was initially terrifying, you eventually just trusted his expertise behind the wheel. The canyon, its rich ecosystem, its star-filled nights, and the kindred spirits inhabiting its corridors became Darek’s home away from home. As much as he loved the climbing, he savored the beauty and tranquility as much. He always said there was nowhere he slept better.

Author of dozens of routes there, community organizer, liaison with the City of Rifle, friend to anyone and everyone who met him in the canyon or around a campfire: Darek was all of these things and much more. His last route in Rifle was Freewill (8a / 5.13b), in 2020, while other recent ones closer to home were Social Dispensing (7a / 5.11+), River Wall, Button Rock, in 2020, and Super Tuscan (5.13b), Seal Rock, the Flatirons, 2018.

Steven Hobbs posted this on the Rifle Climbers Facebook page:

“Darek was a pillar in our community and a treasure of a man. He brought joy and laughter and love to everyone. He is irreplaceable.” To that he adds, “Darek was warm and welcoming to novices and experts alike. He was the unofficial mayor of Rifle not just for his route development and community organizing but because he made everyone feel like they belonged.” Lee Sheftel, who worked with Darek on the Rifle Climbers Coalition (Darek was acting president), mourned the loss of his friend’s “endless energy and devotion … as well as his welcoming smile.”

This past year, Darek at 56 was in perhaps the best shape of his life—lean, strong and psyched. We obsessed over a local project—at the River Wall near Lyons, Colorado—and planned bucket-list trips. He would occasionally lament the onset of age and the physical decline that is coming for all of us, but he was as spirited, engaged, and positive as ever.

There were days where we just couldn’t believe how little progress we were making on our project, and wondered how the same moves would have felt a decade or two earlier. Comparing a 50-plus-year-old body to its previous, younger version is neither fair nor inspiring, thus we began contemplating how were going to look back at this time, 20 years from now, and reminisce on how fit, strong, and free of pain we were at mere 50-somethings. Darek started the mantra: “THESE are the best days of our lives!”. And from then on, in his endearing pitch and accent, he exclaimed it everyday we dropped down into that canyon.

Darek and I were friends for over two decades; he and his family had become my family. Even more than the climbing partnership, I will miss our daily conversations, dinners, morning coffee, his endearing idiosyncrasies, sheer kindness, openness, and selflessness. The connection he made with my three-year-old son is perhaps the most volatile component of my grief. Ethan will never have another Uncle Darek or know anyone remotely like him. None of us will.

Five days after Darek’s death in an avalanche while backcountry skiing on Berthoud Pass, I’m reminded of an afternoon he called last summer. I assumed we were going to discuss River Wall logistics over dinner at their place or mine. Instead he said he wanted to walk over and wash my windows, they needed a cleaning, it was bothering him, and he wanted to do it that evening. He showed up at our door with his full pro setup from 20-plus years’ prior—squeegee, spray bottle, rags, scraper, and bucket. Ethan was ecstatic to be in Darek’s presence, and happened to be wearing a near identical outfit. It was one of those ephemeral moments that I’ll keep close. You’ll always be with us, Dariusz.

Friends have organized a GoFundMe to help with recovery, transportation and memorial costs, and aid the family through the transition.

—Ed McKeown

Ironically, at this time last year Darek wrote an eloquent obituary for his friend Ben Walburn, taken by cancer. In Ben’s illness Darek helped care for him, took over his finances, and raised funds by rallying the climbing community.

Marylee Harrer

63, December 21

Courtesy of the Harrer Family

Nearly 50 years of rock climbing: Marylee Harrer began in 1973. Born and raised in Scottsdale, Arizona, she was first taken climbing by her best friend, Scott Baxter, to Echo Canyon of Camelback Mountain and Pinnacle Peak, and fell head over heels in love with the sport.

At the time, the Arizona Banditos, a rough and rugged group of rebel climbers, were establishing bold ascents on sandstone spires in Sedona, long runout lines on Granite Mountain, and hard crack climbs at Paradise Forks. Marylee became one of the only women in that corps, helping set the stage for high-level climbing for female climbers around the country. She was especially good at technical slabs and mixed cracks, and in her later life fell in love with sport climbing.

In 1979, Marylee got the first female ascent of Mt. Hayden in Grand Canyon, a now coveted summit by climbers around the globe. In 2012 at the age of 55 Marylee achieved a lifelong goal of climbing the Northwest Face of Half Dome.

When asked in an interview who her role models had been, the longtime hard climber Bobbi Bensman gave the names of Lynn Hill, as might be expected—and Marylee Harrer. Marylee became great friends with both Bobbi and Lynn, and they had all planned to climb together, again, in Colorado this year after Marylee recovered from recent knee-replacement surgery.

Bobbi says in an email: “In 1980, I was a sophomore in high school and got into rock climbing on the granite around Phoenix. I was climbing 5.7 and at that time, the hardest known grade was 5.10. I kept hearing of a woman in Flagstaff that was climbing 5.10!!! I was so blown away and knew that I had to meet this woman, as I was the only woman rock climber that I knew of. She was strong and graceful and competent on and off the rock.”

The two had a friendship of 40 years, with Marylee reaching out weekly to check in. She supported Bobbi’s climbing achievements until the end of her life.

“I was actually working on an 8a of Darek [Krol’s] in the Flatirons, and I would FaceTime with her up at the base,” Bobbi says. “It was always so fun FaceTiming with her, and she would always pick up!”

In December of 1981, I was born, Marylee’s first daughter, and in February of 1983 her second daughter, Holly, arrived. Although a single mom, Marylee was wildly successful at continuing to climb and maintain her passion, while dedicating everything in her life to her daughters. Holly and I spent childhoods at the crag with Marylee. In 1988 we moved from Ojai, California, where my mom was working for Chouinard Equipment, when she took a job with the Patagonia mail-order program in Bozeman, Montana. In Bozeman, she continued to climb, and every year she would take Holly and me to the City of Rocks, once in the summer and once in the fall. We would spend our days at the base of the granite cliffs in the high desert sun, playing with sticks and anthills, watching our mother climb, and learning the joy of climbing through being with family.

To this day my mom has remained my favorite climbing partner. This past October we spent a week in the City of Rocks, just the two of us. It was one of the best climbing trips we’ve ever shared, and the last time I saw her. She was there for my hardest sends, as well as all the other pieces of my life.

Marylee and Holly always had so much fun together as well. Holly remained in Bozeman (I live in Flagstaff now) and would spend time walking around town, hiking, biking, laughing and singing. They loved being outside together.

In 1990 Marylee became a certified massage therapist in Bozeman, and continued her practice until her passing day. For 30 years she touched and healed people in the community and from around the world. Her incredible healing touch, commitment to her kids, family and friends, combined with her strength and grace from climbing, had a powerful and lasting effect on all who knew her. She was a force of nature, deeply loved.

Bobbi says: “She was very strong-minded, opinionated and had a such a will to live life at its fullest. … She [also] had one foot in ‘other worlds’ and was very sensitive to everything around her.” Thoughtful and expressive, Marylee regularly kept journals.

Bobbi Bensman

In 2011 Marylee married Steve Barber. Steve proposed to Marylee at Bridger Bowl on a ridge between the chutes Sometimes a Great Notion and Cuckoo’s Nest—a testament to the adventurous and playful love that was the basis of their marriage. Steve and Marylee avidly mountain biked around the country together and traveled the world, to Mexico, Costa Rica, Ecuador, Peru, the Galapagos Islands, Canada and Alaska. While mountain biking in the U.S., they traveled together in their home away from home, a Dodge RoadTrek van.

My mother passed from a severe brain bleed, after presenting signs of a stroke, on the winter solstice of 2020 with chalk in her fingernails, having just been climbing. On the evening of December 29, over 100 people in Bozeman, with others joining remotely (including Lynn Hill in Hueco and Bobbi in Boulder), took a full-moon walk in her honor. She is survived by her daughters, Amylee Thornhill and Holly Thornhill George; her granddaughters, Mesa Thornhill, Louise George and Aven Byrd-Thornhill, her husband and her stepdaughter, Kate Skuntz.

Marylee’s dear friend Randa Chehab, with whom she shared much, including a presence at protest marches in recent years, posted on Facebook: “Such a sudden and profound loss for so many of us. I have been so blessed to know her and love her for the last 26 years. Never any bullshit. She always had my back. She was my champion, big sister, mentor, and confidante. God, I miss you. You have a piece of my heart … It was an honor to walk beside you.”

There will be an outdoor celebration of Marylee’s life in summer of 2021 in Bozeman. Please stay tuned via Facebook for details.

—Amylee Thornhill

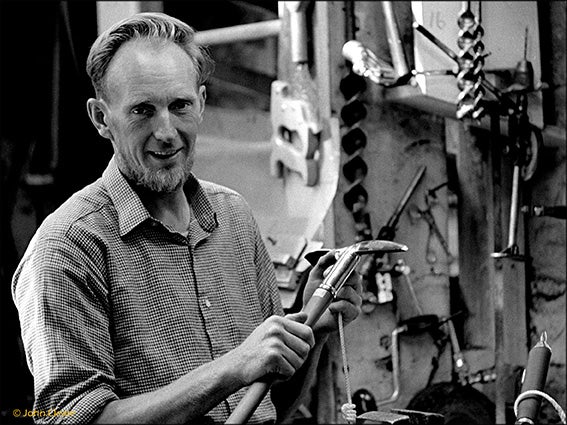

Doug Scott

79, December 7

Even in his final illness, Doug Scott was his irrepressible self, hauling himself up the short flight of stairs at his home in Cumbria to raise money for Community Action Nepal (CAN), the non-profit he started in 1989 to help the people of Nepal who had helped him. The stair climbing was part of CAN’s Everest Challenge 2020, a way to raise money during lockdown, as the regular supply of funds, most often Doug giving public lectures, was no longer possible.

Doug had dressed for the occasion in the old windsuit he wore on the summit of Everest in 1975 during the first ascent of the southwest face. Dougal Haston’s picture shows him standing gloveless in the dusk next to the old Chinese tripod, ready for anything. He needed to be. That morning he had left the tent without wearing his down suit because it constricted his movement too much. Under the windsuit was silk underwear, cashmere and nylon pile. It would soon be dark and their headlamps failed as they abseiled down the Hillary Step. A bivouac was inevitable.

Back at the south summit the pair hunkered in a snow cave, the highest anyone had ever spent the night, ill equipped, their oxygen exhausted. As night wore on they began hallucinating. Doug found himself talking to his feet, “which had become two separate, conscious entities sharing our cave.” His left foot was complaining that it felt ignored, so he took his boot off and discovered it wooden with cold. He pummeled it back to life, and Haston unzipped his down suit to put it against his belly. When dawn allowed them to start down, not only were they still alive, neither man had frostbite. Doug didn’t feel lucky: he felt empowered. His horizons had been broadened. “I knew from then on,” he wrote in his memoir Up and About, “I would never again burden myself with oxygen bottles.”

Scott died on the morning of December 7, at 79 years old, following a battle with brain cancer.

His success and miraculous survival cemented Doug’s reputation for strength, “both physical and mental,” as Jim Duff, doctor on the 1975 Everest expedition, put it. Duff saw his friend as “a force of nature with a wry sense of humor,” and shared Doug’s deep interest in spiritual discovery, reading the I Ching—the “Book of Changes”—and studying Buddhism. That combination of strength and curiosity, coupled with an almost frightening level of energy, were the hallmarks of Doug Scott’s career, one that straddled a revolutionary period in alpinism as siege tactics gave way to alpine style.

“Of all the post-Second World War British mountaineers,” Sir Chris Bonington told Rock and Ice, “Doug Scott was undoubtedly outstanding and joins the rich pantheon of international pioneering climbers from around the world.”

Bonington himself discovered just how outstanding Doug was during the first ascent of the Ogre in Pakistan’s Karakoram range, an ascent Doug wrote about in his history of the peak. Once again Doug was pushing hard late in the day to snag the summit, Bonington fighting to keep up. Abseiling at an angle back down the difficult headwall, Scott slipped and swung, breaking both his legs. Marooned at 7,200 meters with no possibility of rescue on a mountain of considerable difficulty, Scott crawled back to base camp in worsening weather, helped down by his teammates Mo Anthoine and Clive Rowland. It became one of the great epic stories of mountain survival, captured in a photo of Doug crossing steep ground on his knees, teeth bared against the storm. … [Read the full obituary here]

—Ed Douglas

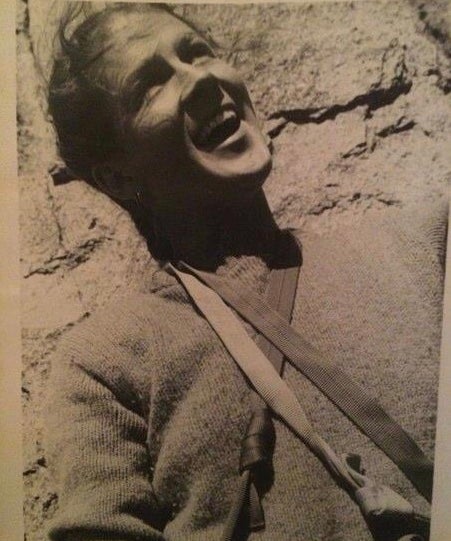

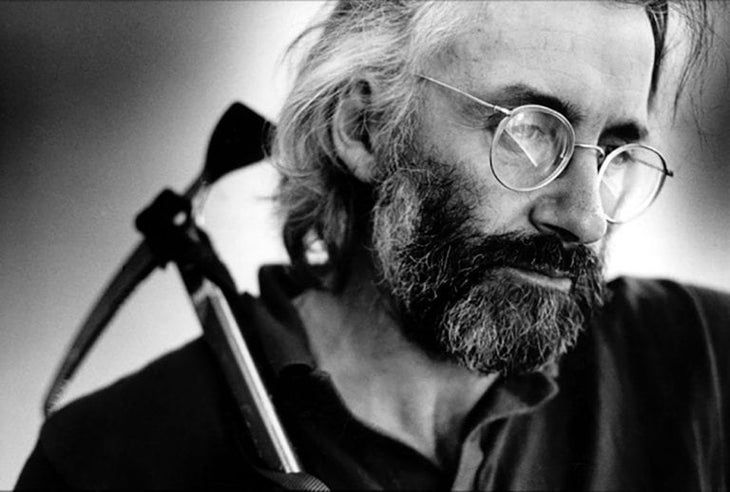

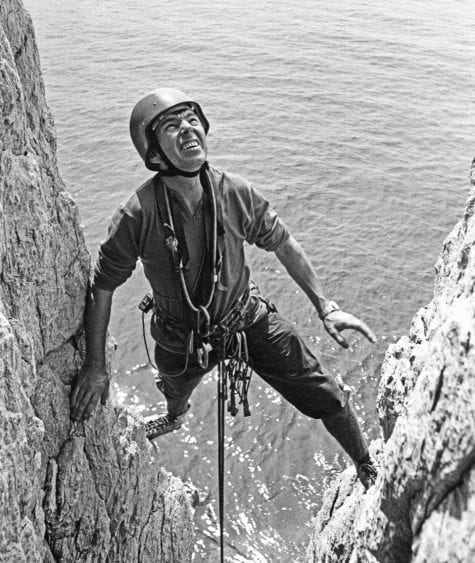

Hamish MacInnes

90, November 22

Update: John Cleare, British filmmaker and photographer, writes: “Hamish was cremated after the hearse, en route to Glasgow, drove slowly through Glencoe so the villagers could bid farewell while a piper played. There will be neither funeral nor committal as he didn’t hold with such affairs.”

Hamish MacInnes did it all—free rock climbing on the summer cliffs of Glencoe, aid climbing on the towering aiguilles of Chamonix, ice climbing in the rugged gullies of Ben Nevis—but he did it with the vision of a mountaineer. Scotland is like that: most of it is Big Country, especially in winter, and Hamish treated it as such. In his career, Hamish changed the sport, from the types of routes that were climbed to the types of routes that could be climbed safely with his technical innovations (like the Terrordactyl ice axe—more on that below) and vision for the future of mountain rescue.

Hamish died on November 22 at 90 years old. He passed away peacefully in his sleep. Most of his climbing friends and contemporaries perished more dramatically, in mountain accidents, but Hamish was a canny old fox and survived his many adventures—and misadventures.

Born in 1930, Hamish came to climbing as many other young Brits did: After World War II, all of Britain was in a severe economic depression and Hamish and many others were laid off from their jobs. Some of them left the squalid and silent shipyards along Glasgow’s Clyde River and went to live in the mountain caves of nearby Arrochar, an excellent base for exploring the surrounding schistose cliffs. Against this backdrop, Hamish began climbing with the Creagh Dhu club, an apprenticeship that gave him the technical know-how to realize his own plans were far too wild and unruly even for even the wild and unruly Creagh Dhu Mountaineering Club. He honed himself into a stoic, fiercely independent adventurer.

The successes came quickly: He established a spate of hard and daring new routes that signaled a new technical level of difficulty for Scottish winter climbing. In 1953, at just 23 years old, he did the first winter ascents of Raven’s Gully (V, 6) and Crowberry Ridge Direct on the Buachaille in Glencoe, both with the legendary Chris Bonington. He made the first ascent of Zero Gully (V, 4) on Ben Nevis with Tom Patey in 1957, chopping steps up the steep snow and ice, an ascent ahead of its time in difficulty. Later, he ventured over to France and was one of the first British climbers to do the Bonatti Pillar of the Dru, in Chamonix. In 1965, he completed the first winter traverse of the Cuillin Ridge on Skye in a two-day period.

Those achievements should be known to all climbers—he was a Grand Master among Scottish climbers. But to me, Hamish MacInnes became a lot more than just a famous climber. His outrageous and daring example inspired me to try and make a mountain life and career work for myself, too. As a boss and mentor to me when I followed his path and became an instructor, he was a role model of discipline and professionalism. And as a friend, he was someone you could Ride the River with. … [Read the full obituary here]

—Rusty Baillie

See also this obituary in The New York Times.

Annabelle McClure

29, November 2

Annabelle McClure began climbing with her father, Dan McClure, at age 6. Born in North Carolina, she grew up in Colorado, where Dan taught her to climb in Garden of the Gods and brought her on first ascents on Pikes Peak. His passion for climbing seeped into Annabelle’s bones and though when she was a teenager it was “that thing my dad did,” she came back during college and then she was in for life.

Annabelle left this world after a car accident. Those who knew her remember a radiant smile, bright blue eyes and energy that could light up the coldest of bivies. Annabelle’s family and friends loved her dearly and knew her as compassionate, intelligent—and stoked.

Annabelle and I met several times through friends while we were both in school at UCCS (University of Colorado, Colorado Springs). Once we finally got to know each other, we had one of those moments that went like this: “You climb? And snowboard? Mountain bike? Raft? And do yoga? We should be best friends!”

We would climb after class in the Garden with a handful of slings, hexes, and a cam or two. Dan and Annabelle taught me to hip belay and equalize two marginal nuts for a bomber piece. Annabelle was the first woman I ever climbed with—and the best climber I, or many others, have ever known. Her pure talent, endless motivation, and vision for the best adventure made her a solid climber and partner.

After graduating in 2014, Annabelle moved to California and scored a biochemistry job in Santa Cruz. She was on her surfboard at sunrise and sunset on weekdays then her bike, snowboard, or a wall in Tahoe or the Valley on weekends. While living the Cali life, she climbed Half Dome, the Nose, the Steck-Salathé and more. As we stood at the base of the Nose for our first time on El Cap in 2016, she told me, “If you imagine every breath in your life, it’s overwhelming. If you just breathe, it’s doable.”

In 2017, Annabelle and I joined the Access Fund National Conservation Team and were on the road for two years. We travelled to over 20 states and 50 climbing areas. She was an excellent trail builder, passionate educator, and inspiring climber—often onsighting hard routes at Cochise, Index, Tensleep, Indian Creek, Devil’s Lake, Eldorado Canyon or Tennessee Wall with a humble attitude of gratitude and joy. We climbed the Nose twice, including NIAD (Nose in a Day) with Hans Florine and Hilary Harris. Annabelle was always psyched to rope up with local climbers to get to know the climbing area, its history, and the community. To recount all the climbs she did during this time would take a book that would read like an extended (and exciting) version of the Fifty Classics.

After road life, Annabelle settled in Boulder, working as a construction project manager. She stayed deeply involved in the climbing community as a trail builder for Front Range Climbing Stewards and board member for the Action Committee of Eldorado. Back on her sunset and sunrise routine, she would climb the Flatirons before breakfast or Eldo after work, and took off on the weekends. Annabelle was on a mission to climb all of her dad’s first ascents throughout Colorado and Wyoming, many of which she did; she could hardly wait to talk to Dan about them. This past summer, she did several linkups in Rocky as well as the Casual Route on the Diamond of Long’s Peak in under six hours car to car. On Pikes Peak, she biked 20-plus miles to climb 500+ feet on the Pericle in a day. Shortly before her death, she onsighted Veterans of Vertigo (5.12- R, eight pitches), Perfect Art (5.12, five pitches) and Stoned Oven (5.11+, 13 pitches) in the Black Canyon of the Gunnison in a weekend—with a broken foot from a previous metatarsal injury.

At the base of a big route or top of a gnarly cliff, Annabelle would often say, “Well, nothing left to it but to do it!” She was a special kind of sandbagger—the kind who wanted you to have the best experience and so she sometimes left out small details, then laughed about it later, saying, “I knew you could do it!” She was an insanely accomplished climber—but, more than that, a daughter, granddaughter, sister, cousin and best friend.

From a remembrance from Dan, Dana, Fletcher and Clara McClure: “Annabelle lived life big! There were never enough hours in the day for our Annabelle. She would happily rise before dawn to climb a rock, ride a bike, board a slope, paddle a river or for any other opportunity that allowed her to live the ‘fullest day.’ … She found peace, challenge, comfort, and inspiration while being outside. Please go for a walk, hike, ride, or climb and keep ’sending it’ to remember our Annabelle.” The family asks that any gifts on her behalf go to the Access Fund or the Action Committee of Eldorado.

To read the statement from her family, go here.

—Andrea Hassler

Dave Altman

68, November 10

Dave Altman died in a catastrophic accident in his parked-vehicle home near a climbing gym in Berkeley. He is mourned and remembered as a giant by his many friends in the Bay Area and Yosemite climbing communities for his superhuman strength, intelligence, artistic talents, kind heart, and generosity and humility as a mentor.

Dave’s longtime friend Yuko Matsumoto, who joined him on powerful overhanging bouldering circuits at Indian Rock in the early 1980s and has remained a close friend, observed: “He was a true renaissance man, as someone who reached and sustained the highest levels of accomplishment as a mathematician, craftsman, musician, bodybuilder and climber throughout his life, out of the sheer joy he found in each of these pursuits.” She was a top climber of her era as well.

In an email last year, Ray Jardine, with whom Dave made many first ascents, including of Red Zinger (5.11d) on Yosemite’s Cookie Cliff in 1979, said: “When Dave put his mind to something, it was a done deal.” On hearing the sad news recently, he added: “Dave was a great guy, super talented, very strong and nice to be around. I enjoyed climbing with him very much.”

Of that 1970s era, another regular partner, Rob Oravetz, wrote in an email: “While the Stonemasters ruled during those days, Dave quietly went down his list, methodically ticking off the hardest cracks in the valley in true old-school form, bottom to top, no hangs, no pre-placed gear … If he couldn’t get up something, [his perspective was that] he wasn’t strong enough. It morphed into lifestyle built around training as an end in itself. We once did a continuous set of 1,000 pullups. A big mistake for me—I have tendonitis to this day …This was all pre climbing gyms, no cell phones, no laptops. If you climbed, it was on rock outdoors, which meant a lifestyle without an all-consuming job.”

But Dave did turn that lifestyle into his role as strength-trainer-in-residence, literally, at Touchstone Gym (aka the Berkeley Ironworks) in Berkeley. Copies of climbing magazines are normal at such a venue, but his longtime friend Scott Frye, a gym employee, made sure that Dave got his monthly issues of Science News and Sky and Telescope, or Dave would be searching for who might have diverted them. Frye said the accident occurred on a cold night and believes that Altman’s propane heater leaked, creating an explosion.

Dave offered tutoring through college level, as posted on his Institute of Original Studies: “Trouble with trig? Still don’t understand Taylor’s Theorem – & the exam is next week? How DID Wiles prove Fermat’s Last Theorem?” he asked students. He also kept a treasure trove of meticulous notes on his climbs and studies in topology and cosmology for the benefit of others.

John “Verm” Sherman said, “Many of the climbers who came from Indian Rock origins spread out and often contributed to raising standards across the country.

“Dave stayed true to his Berkeley roots and was a crucial link between multiple generations of Indian Rock climbers. As a college town Berkeley sees most climbers come and go. Dave was different. I can’t see anyone replacing what he meant to Indian Rock.”

Dave studied math at UC Berkeley, then began a graduate program there. He and I met at Berkeley math-department gatherings, which he still attended after leaving the graduate program to pursue climbing and other interests, though he retained his passion for the subject. After I passed my first-year exams, he kept a promise to take me to Yosemite, introducing me to great climbs and to Galen Rowell and others of my heroes. On our ascent of Snake Dike on Half Dome his rope was too short, so he told me that when the rope ran out, I should just unclip from the anchor and go: “I can lift twice your weight, even on small holds, so don’t worry.” We did classics on the Cookie, and he shared tales of John “Yabo” Yablonski, Ray Jardine and other partners. Over the years he explained mathematical ideas I was struggling with, while demonstrating Japanese cooking and the subtleties of his side work translating from and for Japanese research journals. He also showed me how to play “Castles Made of Sand” and other Jimi Hendrix classics on his guitar.

Referring to a comment Dave made during a Touchstone interview that he’d be nearing retirement if he hadn’t taken the road less traveled, Jefferson Cowie, a Vanderbilt historian, emailed: “I sit by the fire, the fat tenured professor Dave said he could have been, thinking of him, the pure form, the warrior climber, the hermit genius of algorithmic life, the twinkle eyed master of rock. A separate reality, indeed. Nobody deserved the ignominious passing Dave faced, let alone the man who defined the nature of the game for so many of us.” Cowie called himself “blessed” to receive Altman’s beta, as “a minor parking lot apostle, an Indian Rock gawker, one who could merely flail on the trade routes before a thing of grace.”

Rob Oravetz similarly summed up many people’s feelings by saying, of his formative days, “It’s the time in my life that I most reflect on and cherish. I really feel fortunate to have been mentored into Yosemite climbing with Dave.”

Please see these tributes, one on berkeleyside.com, also here in the university’s Daily Cal, and this on touchstoneclimbing.com. Please see this fundraiser for a memorial bench in Dave’s name. A gathering of friends will be arranged for its dedication.

—Bob Palais

Ang Rita Sherpa

72, September 21

“He was a great man.” So says Lhakpa Sherpa, who has climbed Everest more than any other woman, of Ang Rita Sherpa, a climber and guide of worldwide renown—who owned an incredible streak in mountaineering and mountain sports.

Ang Rita held the record for most Everest summits starting with his sixth ascent, in 1983, through to his 10th and last, in 1996, all done without supplementary oxygen. While other climbers such as Kami Rita Sherpa (with two dozen summits) have since surpassed his total of 10, Ang Rita still has the most ascents done without auxiliary oxygen, and the only one done in winter without it. (Note: While he summited in winter, December 22, he sometimes receives partial credit in that much of the ascent was before the solstice.)

The winter ascent was his fourth, in 1987/1988, and on it he and a Korean climber were forced into a bivy: “I with a Korean climber lost the way in Everest due to bad weather and spent the whole night just below the summit doing aerobics exercises to keep our body active, which is the only way to survive there,” Ang Rita wrote on EverestHistory.com.

The “Snow Leopard” had been in declining health, with lung and brain disorders, and in 2017 suffered a stroke. He died in Jorpati, Kathmandu.

“He was a very honest man,” Lhakpa Sherpa continues in an email. “He was a little shy but he had a lot of dignity. He put in a lot of effort to give his children an education. He worked patiently with tourists and took good care of them. Many older Sherpas were similar in that regard. I respect him deeply, with all my heart.”

Ang Rita grew up herding yaks and farming with his family, and began working as a porter at age 15. His first summit was Cho Oyu at age 20. He also climbed Kangchenjunga, Makalu, K2, Lhotse, Annapurna, Dhaulagiri and many other mountains.

Pete Athans, another multiple Everest summitter, says, “Ang Rita was just ubiquitous in the ‘80s and ‘90s and really ushered in the age of multi-multi Everest summits among the Sherpas. He and Sundhare [Sherpa] had this competitive spirit where they pushed one another on several years’ worth of Everest expeditions, both of them committed to oxygen-less climbing and, of course, guiding. … It was always fun to be with them: they played hard, and, given their backgrounds, worked even harder.”

Sandy Allan, a Scottish mountaineer who knew Ang Rita well when both guided on Everest, sends this message: “Ang Rita was a super nice and very understated man with lots of humility … like many intelligent humans he did get a bit bored with the mundane and for a few years had an addiction to alcohol but later in life he got through that, which is testimony to his sense of self and discipline.” Various news accounts cite that successful battle with alcohol.

“[On Everest] We rubbed shoulders very often and used to share news of what was going on around base camp,” Allan continues. “He was quite articulate and spoke reasonable English, which was quite something for his generation. Like many of the Sherpas he was very well informed and knew who was who and who had climbed or attempted things.

“He was held up as an icon in his own country and while I think he enjoyed the success he never let it go to his head. He was a very nice man with a wry smile and it was always great to bump into him along the trails and get his news.”

Ang Tshering Sherpa, a former president of the Nepal Mountaineering Association, told cnn.com at the time of Ang Rita’s death, “He was a climbing star and his death is a major loss for the country and for the climbing fraternity.”

Kami Rita was quoted in the Kathmandu Post as saying, “His dedication as a professional climber can never be described in words. It needs determination, passion and courage to climb Everest without the use of supplementary oxygen. Ang Rita did it 10 times.”

Ang Rita’s wife, Nima Chokki, predeceased him. They had three sons and one daughter. One son, Karsang Arohan, a guide who climbed the mountain nine times, died on Everest eight years ago. His other sons are Chhewang Dorje and Furanuru. Ang Rita lived with his daughter, Doma, in Jorpati.

See this news story on climbing.com and this obituary in the New York Times.

—Alison Osius

Ben Kessel

34, September 20

The first time you heard Ben Kessel laugh, you knew that this person knew how to live. Whether you heard it at a crag, a pub, or around a campfire—all were equally likely—the laugh was full-bellied, bordering on a bellow. It was his laugh watching you posthole, right before he sank in, too; and the laugh of discovering an Australian Shepherd, blissfully halfway through devouring our group’s cheese. It appreciated the absurdity of life and celebrated its imperfections.

Ben’s love of adventure started early. He grew up in Natick, Massachusetts, and his mother, Irene, took him on his first hikes in the White Mountains of New Hampshire. She remembered how he was always climbing everything in sight. “When we went hiking in the woods, he and his brother would run over to any big climbable rocks along the way—once they started climbing the rocks, it was hard to get them back on the boring, flat hiking trail,” she said. Ben began climbing outdoors frequently in his teens—first in the Adirondacks, then in the White Mountains—and never looked back.

Ben left Massachusetts for the sunny prospects of California, attending college at the University of the Pacific, where he studied mechanical engineering, before moving on to pursue a PhD at Stanford. He left the program with an MS in 2012.

One night around a campfire up in the White Mountains of New Hampshire, Ben’s friend Asha Park-Carter asked him why he wasn’t Dr. Kessel. In the midst of all the joking and s’mores he became calm and serious: “I realized I loved learning, but I didn’t care about the PhD.” Later, when I asked him what his greatest achievement was in grad school, he replied, “My advisor’s nickname for me was ‘Gentle Ben.’”

Ben used his early departure from school as an opportunity to travel the world instead. He explored and climbed in places including Nepal, Thailand, Australia, Patagonia, Peru, and Jordan. On one of his favorite trips, he met up with his brother, Dan Kessel, in China.

After ending his worldwide trip in Boston, Ben began volunteering with the MIT Outing Club (MITOC). Like most of us, Ben was looking for community; in MITOC he found cohorts who shared his psych for getting outside, regardless of skill level. Ben became a leader in MITOC, spending countless hours instructing and mentoring new climbers. He was quiet in his competence, explaining without pretence. He taught classes on trad placements, led self-rescue practice sessions, and showed others of us how to be effective teachers while staying humble. He would often slip in a lesson so seamlessly that it took months to realize how much he had actually taught you. Ben spent a lot of time teaching us technical outdoor skills, but ultimately, he was really teaching us how to be mentors and leaders in our communities.

Why would Ben spend so much time teaching beginners how to lead climb, heckling from a hammock, or hanging out in ratty cabins, when he could be sending? In the words of his friend David Migl, “Ben’s focus was on the people he went with and the experience of climbing rather than pure technical difficulty. Ben graciously reminded us that we were never going to be world-class climbers, but the point was to get out there, see the views, and share quality time climbing with friends.”

The memories that will stick with many of us from MITOC are of Ben in a cabin up in New Hampshire, sitting in a beat-up, dirty red 1970s-style office chair of which he was particularly fond. It was strategically placed, close both to the stove and to people. Ben turned that chair into a throne. He would park himself there after a day of tromping around in the snow, and draw anyone who sat down nearby into a conversation. Stories would flow, jokes would go from bad to worse, and beers would, somehow, disappear. In that drafty old New Hampshire cabin, Ben was a true source of warmth.

On September 20, Ben was climbing the classic Moby Grape route on Cannon Cliff in New Hampshire, when unexpected natural rockfall occurred on the last pitch, severing his rope. Ben was 34 years old. He is survived by his mother, Irene Kessel; his father, Paul Costello; his brother, Dan Kessel; and many loving aunts, uncles, and cousins.

—Mason Glidden and Asha Park-Carter

Kris Ugarizza

35, September 16

You would usually hear Kris before you saw him. His booming, endearing laugh echoed off the rock walls of wherever he happened to be climbing or shooting that day, followed closely by his “Ladybug” Kyra, a small pitbull he rescued and trained from a bad crag dog to almost a perfect crag dog.

Born in Peru but raised in Wisconsin, Kris, a photographer by profession, called Colorado’s Front Range home for the last five years. When he wasn’t on the road or wintering in El Potrero Chico, Kris would spend a lot of his time sport climbing in Boulder’s Flatirons or at Staunton State Park. He spent many days projecting Ultrasaurus, and it would become his first 5.13a.

A true vagabond though with a sense of home, Kris would spend weeks at a time on the road, traveling to Ten Sleep, Wyoming, or the Red River Gorge in Kentucky, where he would pick up part-time shifts at Miguel’s Pizza: waiting tables, walking around petting all the dogs and making sure everyone had enough for dinner, asking about how their projects were going and how their climbing days had been.

Whether with a camera in hand or not, Kris had a way of making anyone and everyone feel welcome, often inviting people to join his group for the day or setting them up with another partner. Time spent with Kris was filled with deep laughter—and often guacamole, which he would whip up at home for tastings. He always found a way to ask you about how life was going, often asking more about you than offering up about himself.

Kris’s biggest gifts may be his photographs. He worked as a wedding photographer, and here especially his art shone. He found ways of making a couple’s day just a little bit easier and pushing his creativity and abilities to a new level with almost every wedding. In the last couple years, Kris also expressed his talents through climbing photography. He began shooting for outdoor brands and working with publications such as Rock and Ice and Climbing magazines. He had a can-do attitude and was driven to make it as an outdoor photographer, and his career was evolving and growing.

Last February he posted these thoughts on Instagram, following a day climbing with Genevive Walker, Maureen Beck and Emmett Cookson:

“I have not really enjoyed climbing in the past few months. My priorities happened to change without me noticing, to the detriment of my own happiness and growth. … For the first time in months, I felt happy to climb. Just for the fun of it. My friend Genevive and I ended up just catching up, laughing, supporting each other and climbing not because we wanted to send a certain grade, or because we felt we weren’t good enough so we had to train hard. We climbed because we love climbing. If we didn’t send, we laughed, then we tried again, then we failed again, and it was O.K. Failing is OK. … For the first time in a long while, I had no weight over my shoulders while I climbed. No dark clouds covering my sky. Today reminded me what I love about climbing. And it’s not the sending. It’s the support and the joy that comes with the act of moving your body and joking around with a friend.”

On September 16 Kris made the ultimate decision to leave the tangible world.

Chelsea Rude, who called Kris her best friend, posted that he struggled with depression, yet ”was the king of simply showing up, giving love, and sharing laughter. That’s all he had for any and everyone in his life. Nothing but love.”

She gave a telling example of how he accompanied her from Boulder to Vail, Colorado, for shoulder surgery. “He helped me feel confident in my upcoming surgery, shared laughs and guaranteed me that he’d be there for me once I got out.” He looked after her that evening, then was up early the next day to take her to PT, and was patient when she was sick to her stomach all day. ”It didn’t make Kris shy away. Instead he posted up with me to watch ‘Game of Thrones’ and held my hair out of my puke. That was the beginning of one of the best friendships I’ve ever known.” Upon the tragedy, she and other close friends did their best to contact close friends to let them hear it in a personal way: “But Kris made friends everywhere he went, so I think that is an impossible task.”

Kris is survived by his parents, his sister, his adoring pup, aunts and uncles and many, many friends across the global climbing community.

— Alton Richardson

Janette Heung

35, September 5

When you were with Janette Heung, you were walking with a friend. We had many sessions in the gym where more time was spent in the locker room talking than actually climbing. She was always curious and excited about your world, and she carried that passion into everything she did and with everyone she met.

Janette was humble and kind, without an ounce of braggadocio. I knew she ice climbed but didn’t really know. I first understood her level of skill when she spoke to a crowd of 80+ women at the Denver Arc’teryx store, for one of her many sponsors. The first two speakers of the Women of Winter talk were skiers and snowboarders—sports much of the audience was more familiar with; then came Janette. As she shared images of her climbs from Canada, New Zealand, China and of course all over the USA, I—and everyone looking on—was floored by her vertical adventures.

On ice, Heung led WI 5 and 6 routes in many of North America’s best cold-weather climbing destinations. A small selection of those includes: Nemesis (WI 6) on the Stanley Headwall in Banff National Park, Canada; Mummy Cooler IV (WI 5-6) in Hyalite Canyon, Montana; Bridalveil Falls (WI 5+/6) and Ames Ice Hose (WI5 M6 R) in Telluride, Colorado; The Black Dike (WI 4-5 M3) on Cannon Cliff, New Hampshire; Gravity’s Rainbow (WI 5 M1) and Bird Brain Boulevard (WI 5 M5) in Ouray, Colorado; The Fang (WI 5-6) and the Rigid Designator (WI 5) in Vail, Colorado; Alexander’s Chimney (WI 4 M4) and Hallett Chimney (AI 5 M5) in Rocky Mountain National Park, Colorado; the Weeping Pillar (WI 5-6) on Upper Weeping Wall, Icefields Parkway, Canada; and Mindbender (WI 5+) on Mt. Pisgah, Lake Willoughby, Vermont.

Perhaps her crowning achievement was a first ascent (Grade 5) on the South Face of Mount Aspiring, New Zealand, in September 2016, with the guidance of a local climber, Allan Uren, and her partner Lukas Kirchner. She named it Thales.

She wasn’t picky when it came to outdoor recreation, often of the attitude, “Any ice at all is good ice!”

Janette pushed extra hard on many climbs and was usually surrounded by men, occasionally with one other woman for support. The men were not non-inclusive, but they were focused on their objectives (or sometimes drinking). An extraordinary thinker, she desired deeper interactions and community as she tackled the many harrowing climbs; she could talk climbing with the best of them, but wanted more out of the experiences. Nevertheless, you know homegirl persisted and did not complain (and yes, she still joined them for a drink).

Janette excelled in any situation she was thrown into, no matter how foreign. Born in Hong Kong, she made her way to Boston for high school (Exeter), college (Tufts), and graduate school (Harvard). Inthe last several years of life she relocated to Colorado. As impressive as her climbing was, her professional accomplishments were equally so: She was a respected consultant at Deloitte and JWG Global. Her final role was with the University Corporation for Atmospheric Research (UCAR), a nonprofit consortium of more than 115 North American colleges and universities focused on research and training in the Earth system sciences. Janette’s work involved sharing UCAR’s research with the community.

Volunteer time was important for Janette, especially the five years we overlapped on the Young Professional Council of The Nature Conservancy in Colorado, called the 13ers. She was passionate about keeping nature wild and accessible. She had a special spot in her heart for connecting nature to urban areas for youth, having grown up in Hong Kong with minimal outlets.

Her passing from a freak fall while rappelling in the Wind River area of Wyoming was a shock and deep loss to all her communities, climbing and otherwise. As Janette and two friends were rappelling from Pingora in the Cirque of the Towers, rockfall cut the sling anchor to which she was attached. The others in her team were able to grab onto nearby objects or each other, but Janette was unable to react in time and fell 400 feet. By the time her team was able to get down to her, she was unresponsive.

In the 2017 American Alpine Journal, Janette recounted her team’s first ascent of Thales: “After being in the shade all day on the south face, topping out onto the Coxcomb Ridge into the warm afternoon sun felt instantly rejuvenating. We safely reached the summit by late afternoon and carefully descended the northwest ridge. We named the route Thales, in honor of the ancient Greek philosopher’s thoughts on fluidity and mindfulness.” Climbing for Janette was part of her way of life; as much joy as she derived from it, it was not simply about having larks in the mountains, but about reflection and connections with others.

Janette’s mother shared at her memorial that “life is to be lived, not lamented.” As her climbs and thoughtfulness show, Janette did exactly that.

—Laura Isanuk, with Kristen McCulloch and Katie Millard

Rhea Dodd

60, September 3

Update: The Rhea Dodd Fund has been established to support a Kenyan who is working in Kenya to promote animal welfare. The fund is set up through the Vet Treks Foundation, a non-profit that facilitates veterinarians’ travel to developing countries to work with animals. Recipients will be DVMs, vet techs, and others in Kenya who need equipment, special training, or other resources.

The fund is inspired by Rhea’s love of African wildlife and African Indigenous peoples, and her travels with veterinarians to work with Vet Treks and African Network for Animal Welfare of Kenya.

When Rhea Dodd and Teri Savelli sat down with their old friend Chris Blatter and his friend John Seebohm at an American Alpine Club dinner six years ago, they were, Teri said, on “high alert. On fire.” In great spirits.

“She was so funny, like Robin Williams,” says Savelli, who had met her friend of many decades while standing in line for an outdoor-ed course at Evergreen State College. “That kind of genius.”

Blatter’s friend John Seebohm turned to him and said, “I think we just won the lottery.”

Says Savelli, “Rhea always wanted to keep it going. You couldn’t rein her in, even when she was dying. She never wanted to leave the party. She wanted to be where the fun was. Every birthday I had, she got here.” Savelli says her friend once said she “felt like that song ‘Happy’ … ‘like a room without a roof.’”

Dodd and Savelli climbed much in the early years of their friendship, in Colorado, Yosemite and France. After Dodd’s cancer diagnosis five years ago, Savelli drove the six or seven hours from Ophir, Colorado, to her friend’s house in Golden, countless times in support.

Rhea Dodd, 60, climber, triathlete, Tae Kwon Do champion, skier and veterinarian, died in hospice in Denver on September 3, with her twin daughters Alexa and Annalise—two being the visitor limit during the pandemic—beside her. In her illness she received devoted care from her life partner, Gary Kofinas, of Wilson, Wyoming, where she had moved and helped him design and build a new house. They climbed, camped and skied the backcountry, often with a dog along.

“Much of our time together was spent dealing with the challenges of cancer,” Kofinas says, “but in spite of this we had an amazing amount of good times, because of who she was, her warmth and spirit.” … [Read the full obituary here]

—Alison Osius

Gail Bates

103, August 21

Gail Oberlin Bates spent her last morning at home reading the New York Times, engaged in the world to the end—which was at the grand age of 103. She “devoured,” as her longtime friend Malcolm Odell said, analyses of the Democratic Convention, and had already called town hall in her home of Exeter, New Hampshire, to ensure she received a ballot.

She had a stroke that evening and died Friday, August 21, after holding hands with her beloved niece Betsy Bates all day.

Married for 53 years to the pioneering mountaineer Bob Bates, who died at age 96 in 2007, Gail was an adventurous person and avid trekker, and was the first employee ever at the American Alpine Club. She journeyed to remote base camps in a time when they were far more remote than today. Says Laurel Cox, another friend of many decades, “We met Gail at Camp Denali in Alaska in 1966, when she was waiting for Bob’s climbing group to return from Mount Russell. She was a dear friend, and we will miss her.”

Gail was a friend to generations of climbers. Mark Richey, celebrated New England alpinist and 2020 Piolet d’Or recipient, recalls, “She was a wonderful, kind person, and sharp to the end. Not long ago she called to say she had just purchased a new car!”

In 2018, at age 100, Gail was an honored guest at the American Alpine Club annual meeting and benefit in Boston, attending with Jed and Perry Williamson.

Teresa Richey, a Peruvian, relates, “Gail and I met at an AAC dinner in the 1980s. She greeted me very warmly, saying she had heard I came from Peru. I have always appreciated that kind of welcoming attitude, and especially during these tumultuous times I appreciate it more.”

Born in Cleveland, Gail studied Italian and art history at Vassar College, graduating in 1939, then earned a Masters (unusual for a woman in the 1940s) in social work from Columbia University.

During World War II, she served in the American Red Cross from 1943 to 1945, according to a 2017 tribute to her on the Congressional Record on her 100th birthday.

According to that tribute: “She was stationed overseas to England with the Ninth Air Force, where she served with Red Cross Aero Clubs and worked long hours, supporting aircrews and soldiers from 6 AM to midnight … On D-Day, Gail first heard of the Allied landings in Normandy while eating breakfast in a London cafe. She would soon join the Allied armies in continental Europe, arriving in Sainte-Mere-Eglise, France, in July, where she hosted a party for the children of Sainte-Mere-Eglise, providing a brief respite from war for the first liberated town in France. Following Allied victories in eastern France and Belgium, Gail accompanied General George Patton and his Third Army into Germany and was one of only two women who served in the Red Cross Aero Club in Berlin.”

Upon her return to the United States, she gained her job as the secretary for the American Alpine Club, which was then based in New York City. She met Robert “Bob” Bates at an annual dinner, and they married in 1953 and traveled together worldwide. A revered English teacher from 1939 to 1976 at Phillips Exeter Academy, Bob was tapped by Sargent Shriver to serve as the first director of the Peace Corps in Nepal for a year starting in 1962, and the couple moved to Kathmandu. Gail was eager to go, and she took an active role in running the operation.

“She was the first lady, like a diplomat,” says Odell, who was part of the Peace Corps. “She was our rock.”… [Read the full obituary here]

—Alison Osius

Matteo Pasquetto

26, August 11

On August 11, the day of his 26th birthday, Matteo Pasquetto was laid to rest in Entrèves, Courmayeur, at the foot of the mountain he loved, Mont Blanc. A few days earlier he lost his life in an accident while descending the Reposoir Ridge. He had just established a bold new line up the East Face of the Grand Jorasses with his climbing partners Matteo Della Bordella and Luca Moroni. The others named the route Il Giovane Guerriero (The Young Warrior) in his honor.

He was an exceptionally talented and accomplished young alpinist. Notable ascents included a new route, Il dado è tratto, on the Aguja Standhardt in Patagonia with Della Bordella and Matteo Bernasconi, as well as a possible first repeat of the Ragni Route on the North Face of Aguja Poincenot. In the Alps he climbed the Eiger North Face via the Heckmair Route, Quarzader in Ponte Brolla, Divine Providence on the Grand Pilier D’Angle, and Groucho Marx on the Grande Jorasses, among many others.

Matteo spent countless days exploring the Mont Blanc massif. He and his friend and climbing partner Fabrizio Calebasso had just finished writing the complete rock climbing guide to the Italian side of Mont Blanc, published by Versante Sud. This was his first foray into authoring guidebooks and an adventure I was able to share with him by translating it into English.

While working on the project, I would often complain to him that the descriptions for the approaches were too vague or suggest that routes should be given more detailed explanations. He would have none of it, adamant that guidebooks are meant to act as an eye-opener, a window onto the endless possibilities of the massif, but certainly not something that should diminish the sense of adventure. He knew that anyone venturing into these mountains has to be prepared and conscious of the risks involved; he felt it would be irresponsible to spoon-feed climbers excessive information.

“If you need to be taken to the foot of the route, told what gear to bring and shown how to climb each crux, then what you really need is an alpine guide and not a guidebook,” he would say.

Matteo was an endless source of good humor and crazy antics—more often than not, carried out to the sound of terrible music!—and incredibly humble, his achievements notwithstanding. Many of the stories shared by his friends and climbing partners following his death clearly expressed this duality.

In the words of Matteo Della Bordella, “That broad smile and unwavering desire to talk shit took nothing away from a meticulous preparation, down to the last detail, on all climbs.”

Matteo was a carefree spirit, almost childish in his enthusiasm yet possessed a calm composure that made him seem far older than his years.

When climbing, he would never let me set out on a route without a ritualistic fist-bump (“pugnetto”). He was so reliable with this that many of his climbing partners have adopted it as their own pre-climbing ritual. On one of our trips to Cadarese, I remember him carefully racking all the cams on my harness, lining them up meticulously for the correct placements. I knew the crack was at my limit and I was steadily getting more nervous. Just as I stepped up to start climbing, he looked me in the eye and in all seriousness asked: “So what route are you going for?” Of course he knew, but that playful touch, the fist bump and his joyful attitude washed my anxiety away (I proceeded to take a massive whipper at the anchor, ripping a couple cams).

Seeing his friends rack up on his birthday to climb together, in his honor, felt perfectly in line with his spirit. He left us far too early and still had so much left to give. But he will always be there in a fist bump as we venture into the mountains.

—Francesco Bassetti

Visit a memorial page for Matteo Pasquetto here, and read the words of Matteo della Bordella and Luca Moroni here.

Lauren Sobel

25, August 9

Lauren Sobel hailed from Alexandria, Louisiana—about as far from any rock climbing as you can possibly be in the United States. After high school, she headed for New Orleans to attend Tulane University, graduating in 2017 with a bachelor’s degree in political economy. Entranced by city life, she packed her perpetually overstuffed closet into suitcases and moved to New York.

Lauren’s first foray into climbing was volunteering with New York’s Adaptive Climbing Group, an organization that helps those with disabilities learn to climb. She wanted to meet and rope up with all of the climbers who came to the evening sessions at gyms in the New York City area, from youth groups to disabled military veterans. She was also a frequent participant with CRUX Climbing, an organization dedicated to climbing access within the LGBTQIA+ community. Continuing her allyship, she helped raise funds by organizing events for the Silvia Rivera Law Project, an organization that provides legal services for low-income, primarily transgender and gender-nonconforming, individuals.She cared deeply about the people and communities, and they cared for her, adopting her with loving arms.

All the while, Lauren had a full time job with Bank of America, working as a municipal bond analyst. Somehow, despite her already jam-packed life, she inspired a hundred more “She also..” sentences, many of which I’m only now discovering talking with her family and friends. Her sister, Ellie, said she was working toward an MBA from the University of California, Berkeley.

Lauren Pine, a friend and adaptive climber, remembers, “Lauren amazed me with her knowledge and passion for New York downtown nightlife. She went to events even I didn’t know about, and her passion for this world translated to galas and other high-end events, always with the right outfit and attitude to match.”

Lauren just seemed to have more hours in the day than the rest of us. Each of her passions was only one of many, yet all encompassing and worthy of putting her full heart into.

Though her entire rock-climbing career spanned only 15 months—half of that during COVID-19—Lauren managed to climb at some of the greatest climbing areas across three countries! Whether at her East Coast home cliffs of the Shawangunks or the Delaware Water Gap, Mexico’s famed El Potrero Chico or the towering granite dome of the Chief in Squamish, British Columbia, Lauren loved being outside on the rock.

Only now, stepping back to take it all in, do I understand why her New York attitude frequently overrode that Southern charm when the world around her wasn’t going at her speed. Whether it was a delayed train, slow service at a restaurant, or my sluggish lead climbing, Lauren knew time was precious.

Lauren passed away on the afternoon of August 9, while lead climbing at the Gunks. She was 25. She leaves behind her parents, David and Linda; her sister and brother-in-law, Ellie and Clint; and Parker, her 5-year-old nephew, with whom she loved spending time. Outside of her immediate family, an uncountable number of friends from diverse communities miss her deeply.

Living in the information age, those of us lucky enough to be in Lauren’s life have been left with a record of correspondence. Text messages and emails to read and re-read, and pictures to scroll through. Whether it was pictures of outrageous new outfits for her next extravagant outing, lists of climbing routes she accomplished or was considering, or the cute dog pictures—including of the type of puppy she got for her nephew not long before she passed—that she bombarded her sister with, her messages always seemed like exactly what you needed in the moment, from fun and exciting to solemn and encouraging. As Lauren wrote in her final message to our friend who was having a tough time with new motherhood, “The days are long but the years are short.”

—Eric Christian

Dillon Blanksma

26, July 30

On July 30, Dillon Grant Blanksma fell 600 feet from Broadway Ledge while traversing to the start of Pervertical Sanctuary (5.11a) on the east face of Longs Peak, a behemoth known as the Diamond that sits well above 13,000 feet.

The staging area for the Diamond, magnetic test piece for climbers, Broadway often echoes with chatter and rockfall long before dawn. That morning, at least two other parties reached the ledge ahead of Dillon, four more free-soloed or simul-climbed the North Chimney while he and his partner Brittany Christians pitched it out, a fifth waited at the base, and a stream of headlamps bobbed in the distance—all before sunrise. Most climbers choose to traverse the 4th class ledge unroped, as Dillon and his partner did that morning. One moment, he was 10 feet ahead of her. The next, he fell backward and bounced out of view.

By all accounts, despite the crowds and cold temps, my brother’s psych that day was high and his smile bright. Although we ache from the loss of a brother, partner, fiancé and friend,Dillon’s genuine spirit, unconditional love and alpine stoke guide us in how we remember him now.

***

Born in March 1994 to Joyce and Ken Blanksma in Bozeman, Montana, Dillon grew up camping, hiking and backpacking in the Rocky Mountains with his five siblings—Heidi Mae Burger, Derrick Jay Blanksma, Katie Joy Blanksma, Trenton Wayne Blanksma, and Kevin Michael Blanksma.

Under Trenton’s tutelage, Dillon’s outdoor interests narrowed in on climbing. At 17 he encountered his first boulder problem in Yankee Jim Canyon on the Yellowstone River and dispatched his first sport leads in the Bear Canyon, minutes from Bozeman. For the next several summers, spanning Dillon’s high school and college years, the brothers would climb all across the Madison, Beartooth and Absaroka ranges of Southwestern Montana and Wyoming, from deep-water soloing above crystal blue alpine lakes to bagging their first serious summits, Granite Peak (12,807 ft) in 2013 and Gannett Peak (13,810 ft) in 2014.

“That connection we had with climbing is what made him so much more than a brother. He became my best friend,” says Trenton. He saw a new spark ignite in Dillon when he moved to Colorado in May 2016 after completing his degree in computer science from Azusa Pacific University. “Something switched. He took his passion to the next level.”

Dillon’s climbing community grew not only because he was a reliable and competent partner with insatiable psych, but because of his patience and easy way of making anyone feel welcome. The somewhat shy and searching teenager his siblings knew in Montana found his footing and a new lease on life in Golden, Colorado, where he was such a sought-after partner that, rumor has it, to climb with Dillon you needed to schedule three months in advance.

“Alex was a huge part of that shift,” says Trenton. … [Read the full obituary here]

—Katie Joy Blanksma

Jock Glidden

85, July 29

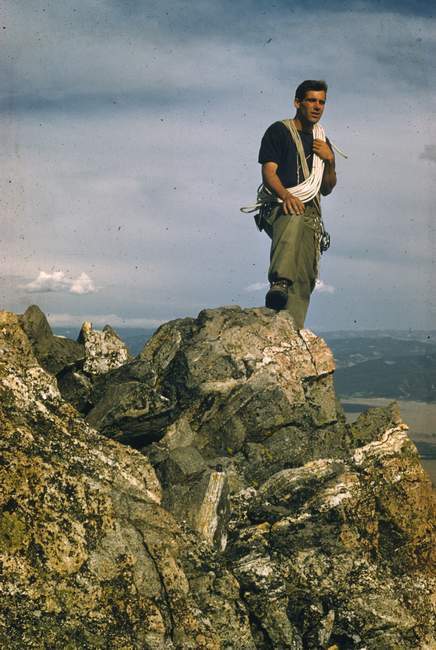

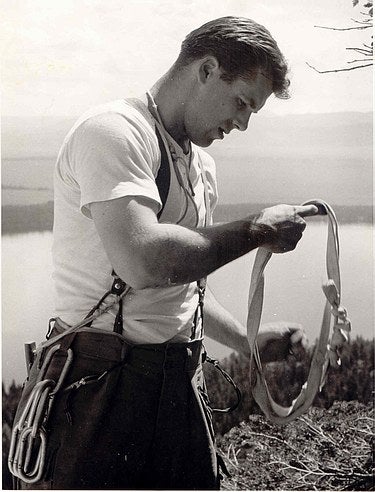

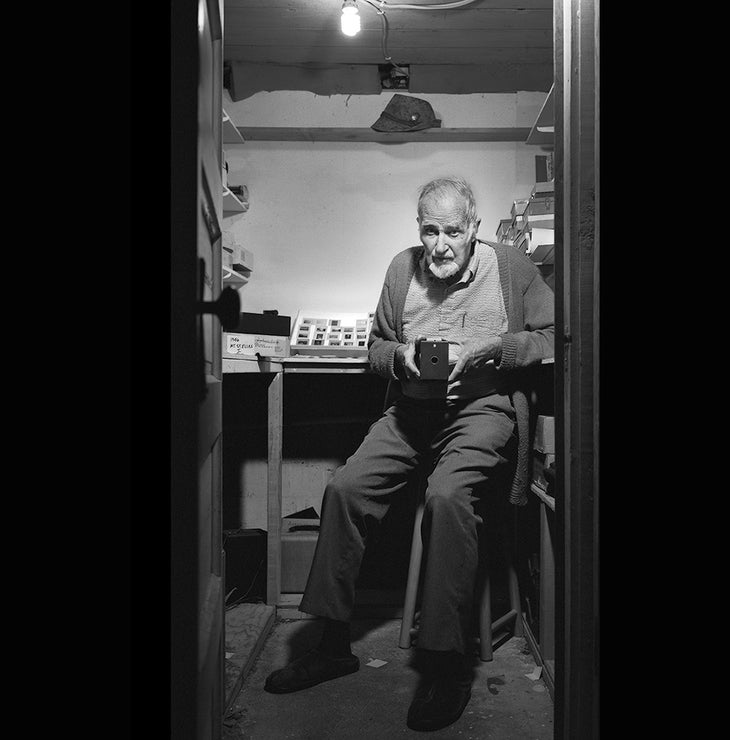

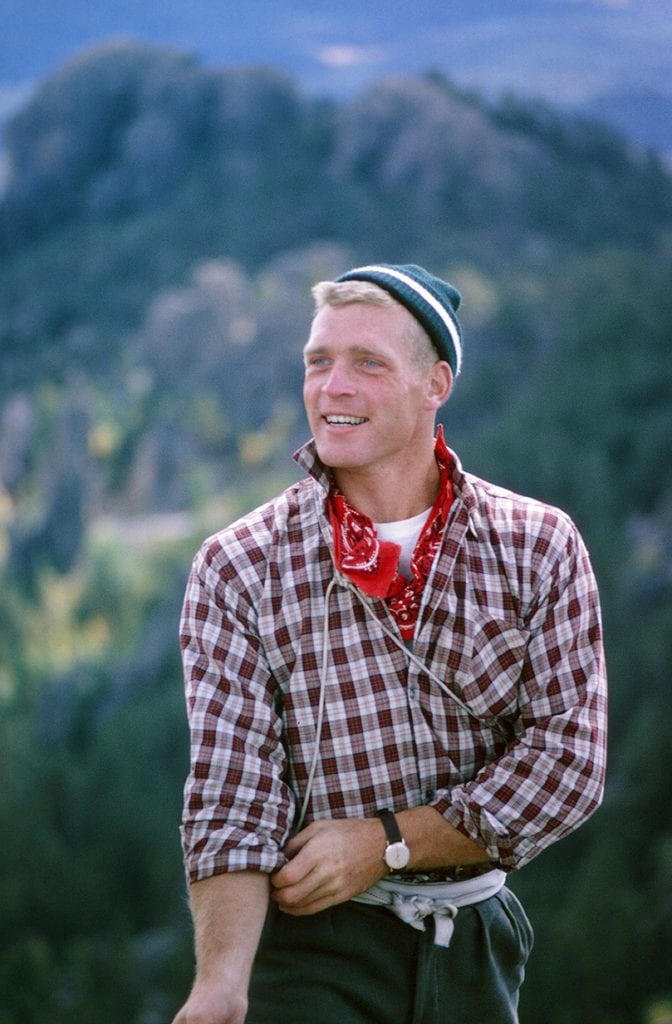

Jock Glidden was a climber’s climber, capable of moving fast in the mountains and comfortable on a variety of terrain. His accomplishments ranged from a roundtrip speed record of 4 hours 11 minutes on the Grand Teton that stood for a decade, to the first ascent of the North Face of Mt. Alberta, to participation in the infamous 1974 American Pamirs/USSR expedition.

Jock Glidden passed away on Wednesday, July 29, 2020, at his home in Ogden, after the balance of pains outweighed the sum of pleasures, and he determined that there was no longer any purpose in continuing the struggle against Parkinson’s Disease.

Writes Peter Lev, “Jock was a ‘go-for-it’ climber. He didn’t need ‘excessive protection,’ i.e., a piton or ice screw at waist level for every move. He depended on his superior skill, and instincts, which was the code of the climbing culture during the 1960s, 70s and into the 80s.”

Jock was born on July 7, 1935, in New Canaan, Connecticut, the eldest child of A. Leland Glidden, of Buffalo, and Jane Butler, of St. Louis. He was raised in New Canaan until his early teens, when his family purchased a cattle ranch near the Verde River in Arizona. He spent several years on the ranch until he was sent to the Putney School, in Vermont, where he competed in cross-country skiing and jumping. He then attended Middlebury College in Vermont, earning a degree in 1958, and where he also competed in cross-country.

He attended the University of Edinburgh in Scotland earning his master’s in philosophy in 1963. During this time, he took up climbing and mountaineering in the Scottish Highlands.

He obtained his PhD in philosophy from the University of Colorado, Boulder in 1969. During his time in Boulder he married Roberta Bannister, in 1967. They had a son, Jesse, in 1969, and he was offered a professorship at Weber State that same year. He taught philosophy at Weber State for 29 years, retiring in 1998. He almost never drove to work, preferring a bicycle, or cross-country skis.

He was an accomplished mountaineer. He climbed the North Face of Robson in Canada in 1969. He climbed the North Face of Alberta, a first-ascent route still considered one of the great prizes of the range, in 1972. That same year, he also set the Grand Teton speed record from the Climber’s Camp, which stood for 10 years. He went trailhead to trailhead in a blazing 4 hours 11 minutes.

George Lowe, who shared a rope with Jock on numerous expeditions, told Rock and Ice, “Jock was one of my earlier climbing partners—and someone who made a difference in his local world. We did what we thought was a new route on the Northeast Buttress of Howse Peak in the Rockies (apparently the first ascent was done the year before), did the first ascent of the North Face of Alberta, and the first ascent of the North Face of Huandoy together. Plus I tried to keep up with him cross country skiing when I visited him in Utah. He was an incredible character.” … [Read the full obituary here]

—Jesse Glidden

Jerry Roberts

54, July 4

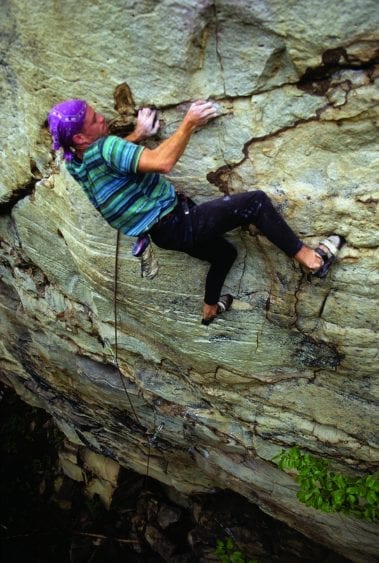

In the summer of 2001, I arrived home from work one Friday night to find a handful of climbers having a toking session on the living-room floor. Not unusual for our house, which at any given time housed half a dozen climbers. A couple of ecstatic guys were holding court, challenging the other climbers to go climb their new routes at the Paradise Falls sector of T-Wall. Despite their excitement, no one was taking the bait: Everyone knew that the sunbaked walls of the Tennessee Wall in midsummer would melt the last off your climbing shoes—if you survived the overgrown and tick-infested 45-minute approach to the base.

“It’s mega, man! You’d crush it. We’re headed there tomorrow. You should come with us!” one of the guys sitting cross-legged on the living room floor said to me. He was a scrappy-looking ruffian. His head was devoid of hair, but his shoulders and arms were covered in thick red tangles of it. He had a droopy eyelid on his left eye, which gave the impression that he had survived the fiercest of battles.

This was Jerry Roberts. He and Travis Eiseman had been developing and sending T-Wall’s hardest lines in the heat of the summer and loving every second of it. More than anything, they were stoked to share it. It took a lot of cajoling and teasing on their part, but I acquiesced. That summer I put up one of my first routes, Burn, right next to one of Jerry’s hardest at T-Wall, The Messenger, using his gas-powered Ryobi drill, which left an ineradicable burn scar on my right calve. I accepted it as a rite of passage. I was one of them now.

Jerry Arvid Roberts, Jr., 54, was born in East Point, Georgia, September 2, 1965. He was the son of Jerry A. Roberts, Sr. and Sonya V. Phillips Roberts. On the morning of July 4, Jerry died after suffering a heart attack at his home. He was a gentle wonder, always ready with a boyish chuckle and a sinister smile.

Even before we met, Jerry was already known as the Godfather of hard climbing in the Southeast, and he helped raise a crop of the best climbers to come out of that area for 25 years. He helped me, and many others, find out who we were on the rock. He gave us a vision of what was possible and what could be accomplished, and never had any ego or possessiveness.

As James Litz, the notoriously elusive crusher from Tennessee, recently wrote on Facebook: “I remember many times lowering off his projects and the first words as I hit the ground were, ‘James great job. That was obviously way too easy for you. You are capable of so much more. Come and check out this other route I bolted.’ Eventually that gave way to, ‘James, you need to get out of here and climb routes somewhere else. I have nothing left for you around here.’ I remember that moment vividly. Like a bird being kicked out of the nest. Within a month I was on the road.” … [Read the full obituary here]

—Luis Rodriguez

Andy Brown

66, June 28

Andy Brown had so much energy that after a full day, he would head to the pub till closing, and then go caving—starting at 11 p.m.

“Why waste daylight when it’s pitch black down there?” he would say, as his friend Steve Rimmer recalls.

Andy will be remembered as wildly funny—with a dry British delivery that could crack up everyone in the room, while he sat straight-faced—yet supremely competent. He was a talented Outward Bound Instructor, a gifted professional ski patroller, a park ranger, a paramedic, and a generous caregiver for his ailing wife, who died only a couple of weeks before he did—of the same illness, and even on the same couch in their home.

He loved to race motorcycles, and was crazy about Elvis, Billy Idol and the Who. As an enthusiastic rock climber for over 40 years, he put up new routes in Estes Park and Buena Vista, Colorado; Pocatello, Idaho; and near his home in Comox, Vancouver Island, British Columbia.

Age 66 at the time of his passing, Andy was born May 16, 1954, in Congleton, near Manchester, England. Rimmer, who met Andy at college in Britain in 1970, recalls starting climbing with him and a close knit group of friends at Ramshaw Rocks in Staffordshire, England. Later Andy climbed in Snowdonia, North Wales, and other venues including the Alps.

In college, Andy studied drama, and later moved on to teacher training in London. There he was legendary for his dancing, which included backflips and break dancing. Later in the 1970s, he became a punk enthusiast, sporting a wild head of red hair. Attending shows for the Clash, Debbie Harry and the Sex Pistols, he would always be up front, pogoing madly.

In 1980, Andy met Johnny Adams in Wales, and they made a plan to go to Yosemite the following year. They climbed the Nose in the fall of 1981, shaken by an earthquake in the middle of the night. It was during that trip that I first met Andy. At the close of their trip, Andy announced he was remaining in the U.S. While Andy was in the Valley he met Susan (Lotus) Steele, whom he later married. They climbed together, and then Andy was offered floor space in a house of climbers in Boulder.

In 1982, Andy met Lotus’s friend Michael Lindsey, who thought Andy would make a good Outward Bound instructor. Although Andy wasn’t an experienced skier, he had taken a mountaineering leadership course in Scotland. Thus began a memorable career as a full-time Outward Bound Instructor, working both summer and winter courses. … [Read the full obituary here]

—Roger Schimmel

Rich Jack

62, June 26

Rich Jack died in a highway accident after a well-lived life when, out adventure motorcycling, he hit a deer near Steamboat Springs, Colorado.

In 1971, Rich moved to Aspen after days as a high school ski racer out of Minnesota. Rich was a well-known figure around Aspen in those days. He wore his thick blond hair long, and at 6 foot 4 inches towered above most other guys. He was active in the ski-shop employee culture, and spent winters cranking out turns—that is, until he met Steve Shea, a climber and another shop rat. Rich was a natural climber and soon became part of our small crew, and we began a frequent partnership.

The first big adventure was our freshman El Cap route in Yosemite Valley in 1973. We’d both done quite a bit of rock climbing by then, but tackling the big stone of Yosemite was how you took it to a new level. We were excited, ready, and no doubt somewhat clueless (though we did have good mentors and lots of training). Yet something had happened that spring to Rich that could have destroyed his mental game.

Rich and Pete Williams were hiking out from Leaning Tower when they encountered a swollen stream and decided Rich would belay Pete across. As things can easily do when you combine ropes with stream crossings, it all went wrong and Pete drowned with Rich looking on and helpless to intervene. A lesser man would have given up the mountain life after that, or dropped into denial and just climbed harder. Instead, Rich embraced climbing but became much more cautious and organized in his approach. More, he also developed a passion for helping others which manifested in his getting medical training and eventually working as an EMT, then a career in nursing; he was to become a critical-care nurse. He would also marry a nurse, Sandy Sandusky, though it was not to last.

Rich not only had come up with the idea for us to tackle Dihedral Wall that fall, but he also ended up being the voice of caution that reigned in the sometimes over-exuberant risk taking I was fond of at the time. In 1973 El Captain had received its first ascent only 15 years before, and wall-climbing techniques were still in the experimental stage. The climb went relatively flawlessly, though things such as hauling our baggage up a cliff would at times turn the day into a vertical circus.

In 1975, Rich (who unlike me was thinking more than 24 hours ahead) came up with the idea of doing a new route on the Diamond on Longs Peak, Colorado. We’d had a taste of how fun it was to do new routes while putting lines up outside of Aspen. We both liked the challenge and creative outlet, and we didn’t mind seeing our names in a guidebook either. On the Dawson/Jack Route, we climbed a few short pitches to reach the base of an obvious seam that looked quite difficult and dangerous. He set up a solid belay while I racked up for what became my first pitch of A5. To this day, I clearly remember looking down at Rich belaying me, and feeling his care, strength and confidence running up the rope. I also remember knocking off a flake of rock that did the perfect curve to make a direct hit on Rich’s helmet. Yes, we wore a helmet for belaying—Rich’s idea.

In 1981 Rich cooked up another scheme. A trio of hardcores in the Black Canyon had recently put up a cutting-edge route they’d dubbed the Hallucinogen Wall. Due to an aura of mystery the Hallucinogen had not yet been repeated. The Hallucinogen was easily one of the toughest things we’d tackled. The route had two cruxes, one for Rich and one for me. Well, actually two for Rich.

A band of overhanging punky dirt-like rock splits the route. The first guys up there had managed to drive in a piton and move, or perhaps levitate, on. In doing so they’d beaten up the crack to the point where Rich couldn’t get anything to hold his weight. He’d bash something in, we’d test, it would pull out. A couple of times he thought he had it, stepped up high, and took a fairly violent fall when the piece popped. This went on for four or five hours. We finally drilled an expansion bolt, which worked but was still marginal and scary.

Next, Rich was up on another pitch and the piece he was standing on popped while he had his finger through the eye of a piton above him. Snap, broken finger. He was in a lot of pain, especially during our last night on the wall, but he toughed it out and was always proud of that second ascent. … [Read the full remembrance on wildsnow.com, here.]

Rich is survived by his wife, C.J. Joplin-Jack; his mother, Charlotte Jack; two sisters, Chip Jack and Liz Bosman; and many other family members. Please see this obituary in the Daily Camera.

—Lou Dawson