Story highlights

Jerry Sandusky published memoir, "Touched," in 2000

He writes of his love for Penn State football and "special" boys

He retired from coaching in 1999, then focused on his charity for kids

Sandusky's charity was inspired by recreation center run by his mom and dad

The college football world knew him as the “Dean of Linebacker U,” the defensive coach who helped Penn State win two national championships. But Jerry Sandusky saw himself as a “Great Pretender.”

It was a name he adopted while performing in a band at his annual summer football camp for children.

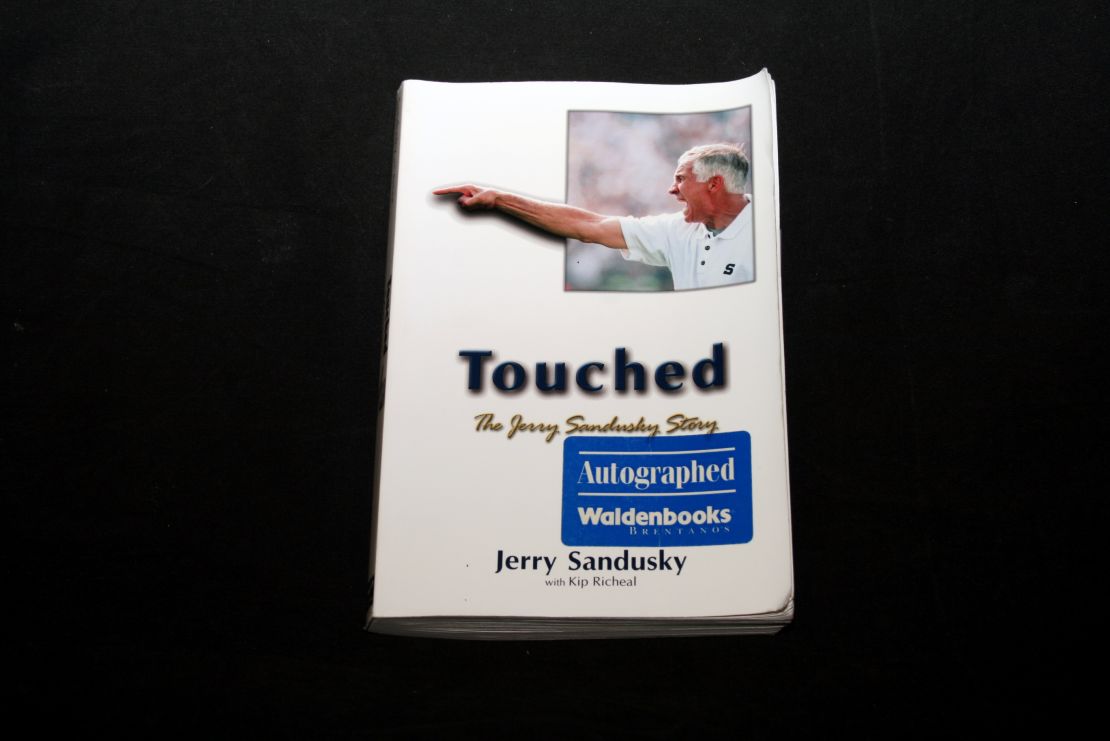

“Pretending has always been a part of me,” Sandusky, now 67, wrote in his autobiography, “Touched: The Jerry Sandusky Story,” published in 2000. “I’ve loved trying to do the right things to hopefully make a difference in kids’ lives and maybe make things better off for them. I’ll never regret being called a ‘great’ pretender.”

Two weeks after prosecutors charged him with sexually molesting eight boys he befriended through his charity, some of Sandusky’s friends, fans and former players are wondering: Did the Great Pretender fool us all?

They are combing their memories for missed signs, clues that could have tipped them that the coach they once assumed was Joe Paterno’s heir apparent may not have been who they thought he was.

Don Lemon: Regardless of gender, rape is rape

His book – so much in demand that its price soared over $100 on eBay last week – provides a glimpse of a man who is not very introspective and admits to his own immaturity.

Even the title, “Touched,” seems creepy in hindsight, considering the sex charges lodged against him and the tender years of his accusers.

“He talks a lot in that book about hugging kids, about loving to be around kids,” editor David Newhouse, whose newspaper The Patriot News broke the Sandusky story, told CNN’s Piers Morgan. “There’s some chilling things in that book, and it’s only when you put them together with the allegations that you can see, perhaps, what he meant.”

Sandusky has denied the charges outlined in a 23-page grand jury report and insisted he is not a pedophile in an interview this week with NBC’s Bob Costas. But he also said he enjoys being around kids, always has. He says he has helped hundreds, if not thousands through his charity, The Second Mile.

Beyond the sex acts and assaults, the grand jury report portrays Sandusky as both controlling and needy. He called one boy more than 100 times after the boy started avoiding him, according to phone records examined by authorities.

In his book, Sandusky describes an exchange with a defiant boy in a psychiatric facility – a child who initially welcomed his visits but grew cold toward him.

“You know, it’s not right to treat people like this,” Sandusky says he told the boy. “You should talk to me.” He adds that the boy “laid into me, screaming from the top of his lungs, ‘Get out of here! Get out of here!’”

In other sections, the former coach writes of wrestling, hugging and swimming with boys. The kids even wrote a rap song about him:

“His name is Jer

You better beware

He has gray hair

But he has no flair.”

Just as his lawyer did this week, Sandusky describes himself as a harmless, overgrown kid. He writes that even beyond his drive to win and perform good works, he has a tendency to push too hard, go too far, and get himself in trouble with his pranks.

“I believe I live a good part of my life in a make-believe world. I enjoyed pretending as a kid, and I love doing the same as an adult with these kids,” he writes. He recalls words spoken by the father he idolized and tried so hard to emulate: “‘Jer,’ he said, ‘you could mess up a free lunch.’”

‘Bug House’ beginnings

When a person rises to great heights and then, unexpectedly, crashes to earth, the search for answers begins with a look at childhood. Jerry Sandusky’s early years, as recalled in his book and by longtime friends and acquaintances, certainly help explain what drove his humanitarian instincts.

But there’s nothing to explain how Sandusky came to be accused of such shocking crimes.

He demonstrates an exceptional fondness for the years he spent as a boy in Washington, Pennsylvania, a small mining town tucked in the state’s southwestern corner, about 30 miles from Pittsburgh. His parents, Art and Evelyn, ran a recreation center, and the family lived in the upstairs apartment.

The center was known as the Brownson House, taking its name from a benefactor – a local judge. Jerry Sandusky called it “the Bug House” because of the colorful characters who came by.

He was an only child, but at the Bug House he never lacked for company. One of his constant companions was a mentally challenged boy everyone called Big Ern. “I used to take Ernie to the movies or we’d go swimming together, and I taught him how to play basketball,” he recalls in the book.

His father coached football, basketball and wrestling and worked hard to embody the slogan on a sign in his office: “Don’t give up on a bad boy, because he might turn out to be a great young man.” He tutored neighborhood children and took in troubled kids, giving them chores and making them feel important.

“Artie had strength and leadership and charisma,” says Larry Romboski, who became a local basketball star under Art Sandusky’s wing. “I know a lot of people benefited from Artie’s work, and I am one of them. I wouldn’t be where I am now without Artie Sandusky.”

Life at the Bug House inspired Jerry Sandusky to create his own charity.

“I was happy beyond my wildest dreams to be known as a Penn State football coach,” Sandusky writes, “but I wanted to do something similar to what my parents did in that recreation center when I was a kid; how they reached out and extended themselves to so many people.”

The name “Second Mile” came to him after hearing a sermon at church about going the extra mile, he says.

“When I heard that Jerry had established The Second Mile, I said, ‘Boy, that’s just like his dad,’” says Romboski.

But while Art Sandusky was seen as a pillar of the town, his son, by his own admission, was a bit of a scamp. He hated schoolwork and reveled in practical jokes, water balloon fights and wrestling matches.

His pranks once landed him in the local jail; it was meant more as a lesson than as a punishment. “My stomach churned at the sight in front of us,” he writes. “The heavy steel bars; the singular exposed light. I vowed to remember my words of despair in that dank and lonely jail cell. The ones to the effect of growing up and cutting out the nonsense. I think Art’s boy has grown up quite a bit since then, but the nonsense? Well, I think there’s still a lot of that left to spread around.”

Sandusky was “not a leader-type guy” as a teenager, says his boyhood friend Bill Lindsay. He remembers him as somewhat aloof. But high school football provided his ticket to Penn State, and Sandusky headed off to Happy Valley to play defensive end for the football team.

His climb to fame surprised many in his hometown.

Says Lindsay: “It was hard to believe he actually became a leader.”

‘Jerry’s Kids’

Football and kids are intertwined in Sandusky’s life.

He married Dottie Gross in 1966, the year he graduated from Penn State. He’d met her at a picnic the previous summer and although he was shy and awkward around girls, his mother pushed him to pursue the relationship.

After brief coaching stints at Juniata College and Boston University, Sandusky returned to Penn State for good in 1969 and stayed through 32 seasons. He and Dottie bought the house they live in today and were happy to settle in State College.

“In State College, it is easy to make great friendships,” Sandusky writes. “The community of State College is a place where people have class and a place where I have always been able to be myself.”

It seemed the perfect place to raise a family. When the couple learned they could not have children of their own, they were heartbroken. They soon turned to helping other people’s kids. They adopted six: Kara, the only girl, and boys E.J., Jon, Jeff, Ray and Matt.

Three of the children arrived as infants, three were foster children, and at least two came through The Second Mile. Jon and E.J. played for the Nittany Lions. Matt was a team manager and Kara graduated from Penn State and worked there.

Sandusky’s two big passions – football and kids – came together in 1977. That year, he was named Penn State’s defensive coordinator. And, with the proceeds from his football book, “Developing Linebackers the Penn State Way,” he established The Second Mile.

It began as a group foster home for eight boys, but grew over the years into a statewide program with an annual budget of more than $1 million, offering after-school programs, mentoring and – according to the charity – free camps to 100,000 children. Heads of large corporations have served as honorary members of the board, as well as NFL greats Franco Harris and Jack Ham, two Penn State legends who starred for the Pittsburgh Steelers.

The children from The Second Mile became known around campus as “Jerry’s Kids.” He brought them to training table dinners, introduced them to Penn State’s coaches and players, took them to games and picnics, bought them gifts and wrote them letters.

Before every home game, the coaches and players loaded onto buses at the practice facility and rode to the stadium as fans stood by and cheered. Sandusky always had a Second Mile boy with him.

“There aren’t many programs that would put up with that,” he told the Centre Daily Times, the newspaper in State College, in 2002. “I will always be grateful for that.”

Sandusky’s book doesn’t dwell much on his gridiron glory days – either as a player or as a coach. His co-author, Kip Richeal, a former Penn State equipment manager, says the coach was so focused on children he had to prod him to include football tales. “That’s what you’re famous for,” Richeal reminded him.

As much as college football fans revere Paterno, they also associate much of his success with Sandusky, the defensive stalwart who helped Penn State capture two national championships with defensive teams that stopped two Heisman winners – Georgia’s Hershel Walker and Miami’s Vinny Testaverde.

Despite the 32 years he spent roaming the sidelines with Paterno, Sandusky’s references to the legendary coach seem to lack any measure of intimacy. He does say that Paterno yelled at him a lot, noticing his penchant for practical jokes early on.

Sandusky recalls how Paterno summoned him to his office in the late 1960s to scold him: “I would like to be able to recommend you for future coaching jobs, but I don’t want to recommend a guy who’s going to act like a complete goofball.”

Sandusky explained their relationship to Sports Illustrated in 1999: “You have to understand that so much of our time was spent under stress, figuring out how to win. That takes a toll. We’ve had our battles.”

Except for his wife and daughter, Sandusky hardly mentions women and girls in the book. Instead, he refers time and again to “special” boys he has grown close to over the years. They meant as much as, if not more than, football.

The walls of Sandusky’s home and office were covered with photographs of children he befriended. “They are kids that have touched my life and have been a part of me for a long, long time,” he writes. “They are people that I can never leave.”

Sports fans often say Sandusky is the best coach never to head a team. Indeed, The Great Pretender turned down opportunities to become head coach at Marshall University, Temple University and, in 1991, at the University of Maryland.

He says he couldn’t bear to part with his foster children or leave his Second Mile kids behind.

“I am tough and competitive with the kids,” he writes, “but the one thing that has never been pretend or make-believe about me is my genuine love and care for the kids.”

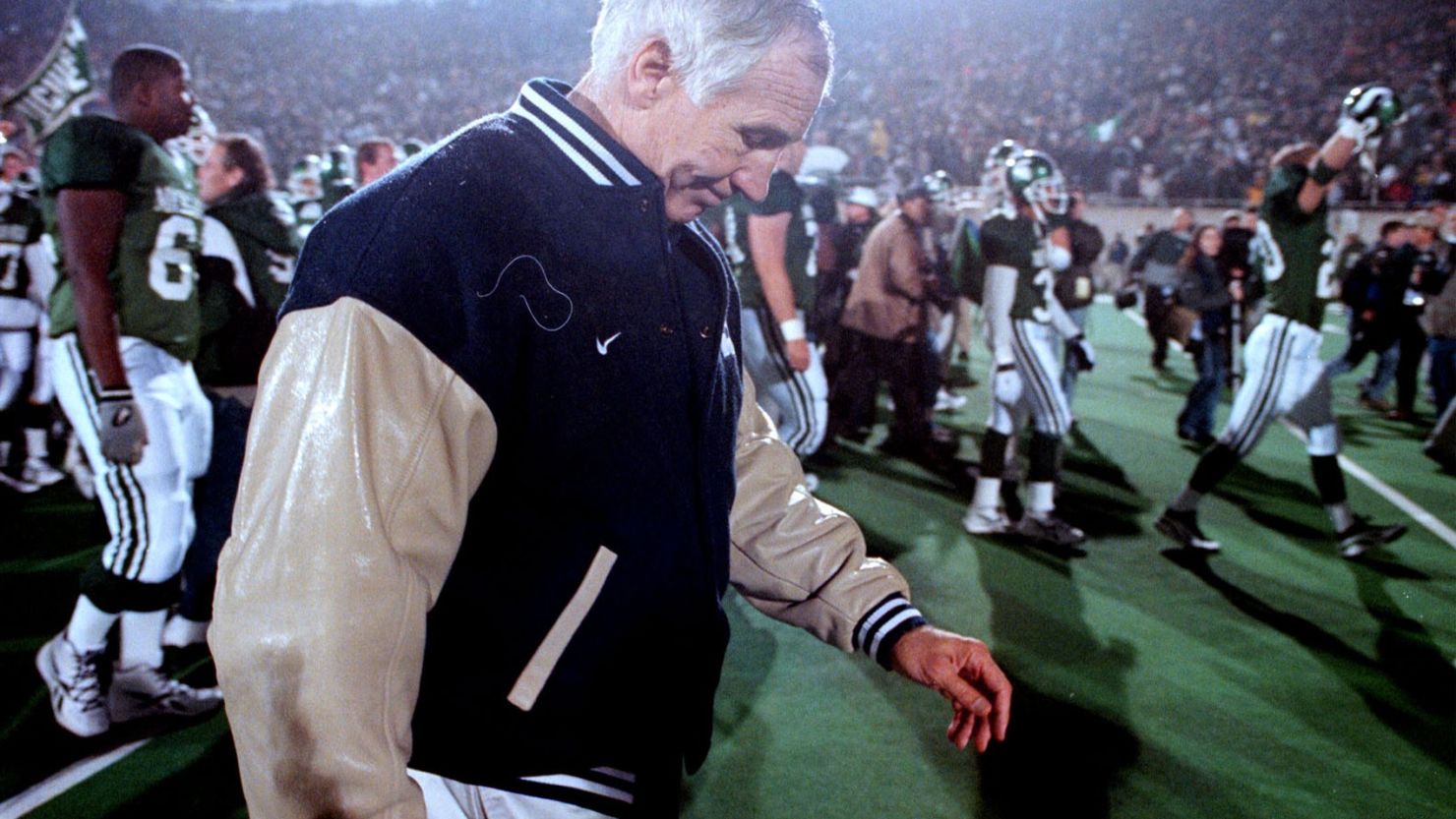

The fall

News of the Sandusky investigation first surfaced in the spring. The Patriot News in Harrisburg reported that a grand jury was looking into allegations of abuse, mentioning just two boys. Sandusky, it appears, attempted to do some damage control.

According to the grand jury report, he called one young man – he had not spoken to him in two years – in the weeks before his accuser was to testify. His wife and a family friend phoned, too; the calls were never returned, the report says.

Co-author Richeal says Sandusky called him in early April “to apologize to me for anything I might read or hear about.” He asked Sandusky if the allegations were true and he responded, “No, definitely not and I’m working on trying to prove that they’re false.”

Richeal says he tried to believe in Sandusky. But he was shaken by his phone interview with Costas, in which Sandusky said he was not a pedophile but acknowledged he “horsed around” with boys and showered with them.

“Even last week I was trying to believe in him,” Richeal says. “But that really upset me, saying that I did shower with them.”

Matt Hahn, who played for Penn State from 2004 to 2007, recalls seeing Sandusky around a lot, though the coach had retired in 1999. He usually had young boys with him but nobody suspected a thing. Hahn had a strong reaction to a suggestion by Sandusky’s attorney that hugging in the shower was what “jocks do.”

“Let me make one thing clear,” Hahn says. “There’s no hugging in the shower between any guys, and nobody is rubbing my back and I’m not rubbing anybody’s back, I can tell you that. You hear a 60-year-old man is showering with a 10-year-old boy, that’s enough for me to say, ‘Whoa, that’s not a good thing.’”

NFL Hall of Famer Franco Harris served as an honorary board member for The Second Mile, allowing his image to be used to raise funds for the charity.

“It still comes as a shock to us about Jerry,” he says. “He reached far and wide, and people that were very, very close to him just had no clue. …

“We all believed in what Jerry was doing.”

Sandusky’s old friends back in Washington, Pennsylvania, are having trouble reconciling the boy they knew with the man many now consider a monster.

The brick rec center once run by his mother and father remains on Jefferson Avenue. The Brownson House still serves the community, but not to the extent it once did. Mines have closed; families have moved on.

Residents who revere Sandusky’s father were proud to see Art’s boy grow into a leader at Penn State.

Now, this.

It brings Larry Romboski, who was mentored by Sandusky’s father, to tears.

“The big question is: Why? Why? Why would he do this?” he says. “His parents have such a great reputation, and why would he in any way try to ruin that?”

The ruins extend far and wide: The scandal tarnished Paterno’s legend and cost him his job. Penn State’s longtime president was ousted, and the athletic director and the financial officer stand accused of perjury and failing to report what they knew to authorities. The Second Mile has announced that it is considering three options for its future, one of which is dissolution. More potential victims have come forward.

The man at the center of it all, the Great Pretender, reveals little of his psyche in his book. But there are legions now searching his words for answers.

“At the times when I found myself searching for maturity,” the coach writes, “I usually came up with insanity. That’s the way it is in the life of Gerald Arthur Sandusky.”

CNN’s Sarah Hoye and Jessi Joseph contributed to this article.