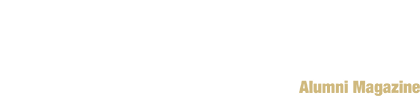

Dalton Trumbo (A&S ex’28), right, with son Christopher at home in Los Angeles, early 1960s. Christopher would champion his father’s legacy.

Hollywood screenwriter and First Amendment champion Dalton Trumbo died nearly 40 years ago. In 2015 he's making a comeback – and looking a lot like Bryan Cranston.

The man from hollywood minced no words.

“Your job is to ask questions and mine is to answer them,” screenwriter Dalton Trumbo (A&S ex’28) lectured a congressional interrogator from the witness table. “I shall answer ‘Yes’ or ‘No,’ if I please to answer. I shall answer in my own words.”

It was Oct. 28, 1947. The Cold War was heating up and the U.S. Congress had summoned Trumbo and nine other film industry workers, mostly screenwriters, to testify in Washington about their political affiliations.

Above all, the House Un-American Activities Committee wanted to know if they were Communists.

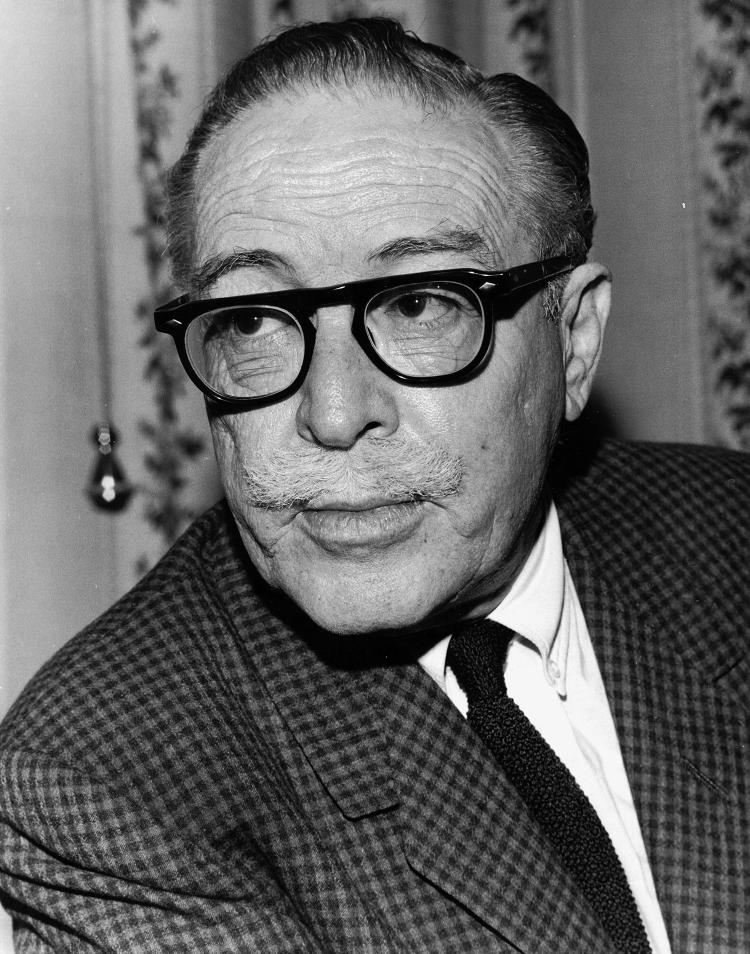

Screenwriter Dalton Trumbo (A&S ex’28) took his work everywhere. Here, in his bathtub, 1969.

Trumbo, the most prominent of the group, the Hollywood Ten, refused to say.

“I believe I have the right to be confronted with any evidence which supports this question,” he said. “I’d like to see what you have.”

Dismissed as uncooperative, Trumbo scoffed: “This is the beginning of an American concentration camp.”

That prophesy did not come to pass, but Trumbo, a married father of three young children, paid for his act of conscience.

It derailed a flourishing, prosperous career, led to prison, prompted a two-year exile in Mexico and forced him into a black-market livelihood for more than a decade.

It also helped make him a civil liberties icon and secured him an exalted place in the history of Hollywood and of Cold War America.

“Trumbo has become a hero to many people,” says Larry Ceplair, a scholar of Hollywood’s blacklist era, during which Trumbo and hundreds of others in the film industry were fired or professionally exiled for their suspected political affiliations.

For Trumbo, who died in 1976, 2015 marks a revival: He’s the subject not only of a major new biography co-authored by Ceplair (it details the congressional appearance) but also of a star-studded feature film scheduled for release in November.

In Trumbo, Bryan Cranston of the AMC hit Breaking Bad plays the title role. The cast also includes Helen Mirren, John Goodman, Diane Lane and Louis C.K. Bleecker Street, the film’s distributor, bills it as “Trumbo’s story and his fight against gossip columnist Hedda Hopper (Mirren) in a war over words and freedom, which entangled everyone in Hollywood from John Wayne to Kirk Douglas and Otto Preminger.”

“It’s almost like it’s the Year of Trumbo,” says Ceplair, who co-wrote the new biography, Dalton Trumbo: Blacklisted Hollywood Radical (University Press of Kentucky) with the late Christopher Trumbo, Dalton Trumbo’s son.

In the decades after Trumbo’s 1947 defiance of Congress he would write the film classics Exodus (1960) and Spartacus (1960), cement his place in Hollywood history and hasten the end of the blacklist. Ultimately he would win two Academy Awards, for The Brave One (1957) and, posthumously, for 1954’s Roman Holiday.

But the road back from exile was long and hard.

Born in Montrose, Colo., in 1905 and raised in Grand Junction, Trumbo entered CU-Boulder in 1924. He edited his high school paper and worked as a professional reporter. At CU he wrote for Silver and Gold, the student newspaper of the day, as well as a campus humor magazine called Dodo.

It was a tough year. With little financial support from home, he constantly labored for money — sweeping the floor of a newspaper office, stoking the furnace of the Delta Tau Delta house, serving meals. He wrote greeting cards on commission.

When Trumbo’s father lost his job as a shoe salesman, the family moved to Los Angeles. Trumbo followed at the end of his freshman year.

Soon his father was dead and the future screenwriter was working nights at an industrial bakery.

“I felt the job was only a temporary one against my return to college in the autumn,” Trumbo wrote in personal papers quoted in the new biography. “As matters turned out…I worked a nine-hour night shift at that bakery for eight straight years.”

During the day, Trumbo wrote furiously. In 1931 he got a start in Hollywood as a magazine writer and film reviewer. This led to a job at Warner Brothers, first as a script reader, then as screenwriter. He subsequently worked at Columbia, MGM and RKO. On the side, he wrote novels and in 1939 won an early National Book Award for his anti-war novel Johnny Got His Gun.

A pacifist and underdog champion, Trumbo actively supported organized labor, civil rights and freedom of speech and association. He joined (and left) the Communist Party twice, decisions that, according to Ceplair, reflected a general affinity for leftist causes and solidarity with close friends who were party members, but not support of the Soviet Union.

“To me it was not a matter of great consequence,” Trumbo said of party membership, according to the book. “It represented no significant change in my thought or life.”

Still, Trumbo was outspoken, and it was little surprise that he became a target for Communist-hunting congressmen. His public defiance of them altered the course of his life and legacy.

A pacifist and underdog champion, Trumbo actively supported organized labor, civil rights and freedom of speech and association.

Convicted of contempt of Congress, he spent nearly a year in prison. Afterward, he moved his family to Mexico and wrote black-market film scripts. When he returned to California, he sought to destroy the industry-enforced blacklist.

The core strategy was the steady production — by Trumbo and other blacklisted writers — of high-quality scripts under pseudonyms. As “Robert Rich,” Trumbo wrote The Brave One, which won the 1957 Academy Award for best screen story.

As some of the scripts became popular films and won big awards, rumors emerged about the true authors, undermining the blacklist and emboldening movie studios to hire some of them openly.

Exactly how and when the blacklist ended remains a matter of debate, but for Trumbo 1960 was a watershed year: Director Otto Preminger and actor/producer Kirk Douglas acknowledged and credited Trumbo as chief screenwriter of two of the year’s biggest films, Exodus and Spartacus.

“This was an enormous breakthrough and drove a stake in the heart of the blacklist,” says Jim Palmer, who retired from CU-Boulder’s film studies faculty last year.

Before long, Trumbo was again working openly and under his own name, with more work than he could handle.

Still, says Palmer, “The repercussions of the blacklist were long-lasting. They went beyond 1960. Proof of that is that Trumbo didn’t receive his Academy Awards [for years].”

In the early 1990s, a group of CU-Boulder students organized a campaign to honor Trumbo on campus.

With guidance from English professor Bruce Kawin and endorsements from Hollywood heavyweights Robert Redford (A&S ex’58, HonDocHum’87), Dustin Hoffman, Katharine Hepburn and others, as well as then-Colorado Gov. Roy Romer (Law’52, HonDocHum’06), the group persuaded the Board of Regents to rename the fountain outside the UMC the Dalton Trumbo Fountain Court.

“It was for a good cause and wasn’t about money,” says Kristina Baumli (MEngl ex’92), a leading member of the student group and now a literature and film scholar. “It was about the First Amendment … It was about integrity.”

On Oct. 17, 1993, a cadre of Trumbo’s friends and fans assembled on campus. Actor Kirk Douglas, screenwriters Ring Lardner Jr. and Paul Jarrico, The Nation magazine editor Victor Navasky and members of Trumbo’s family all were present.

The plaque reads:

Dalton Trumbo: 1905-1976

CU Student

Distinguished Film Writer

Lifelong Advocate of the First Amendment.

Filmmaker Alex Cox, who teaches film studies at CU, hopes the new book and film inspire students to pause at the plaque and consider the weight of their principles.

“That’s a good question for them to ask themselves,” he says. “Because Trumbo put principle ahead of money, at great personal cost.”

Photography by Cleo Trumbo (portrait, Dalton and Christopher); Mitzi Trumbo (bathtub)