A woman in Flushing was arrested in February for changing the locks on a vacant house she owned after she found two men camping out inside. “It’s not fair that I, as the homeowner, have to be going through this,” Adele Andaloro said of the standoff. The same week, another Queens family, this time in Douglaston, said a squatter living in their newly purchased $2 million Dutch Colonial was both refusing to move out and claiming that he was actually the rightful tenant. A few days later, police busted an alleged squatter in the Rockaways in a house full of malnourished animals, DJ equipment, and drugs. In the most horrifying case, a woman was murdered in Kips Bay after walking in on what police say was a pair of teen squatters who had been staying in her late mother’s vacant condo.

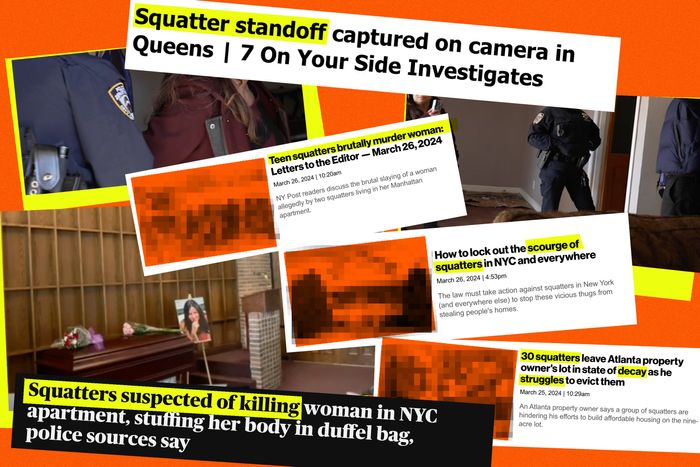

Things are feeling a little anarchic in the world of housing right now, and one reading the tabloids or watching the local news could easily think squatters have taken over the city. (By the end of March, the issue had traveled enough to reach philosopher-pundit Joe Rogan, who devoted an entire episode to New York’s “bananas” tenant laws that are “allowing people to steal other people’s homes.”) A state-assembly member has introduced anti-squatting legislation because, he says, “there is virtually no recourse for when someone is gaming the system here.” Gradually, you can see something like a panic emerging. So is it really squatter season in New York?

In terms of hard data, it’s basically impossible to say — the city doesn’t keep a squatting database — but most signs point to no. “Legally, a squatter is only somebody who entered the unit without any permission in the first place,” says Michael Grinthal, supervising attorney with TakeRoot Justice. And making a successful bid for occupancy or ownership in a situation like that, what’s called “adverse possession,” involves at least a decade of continuous occupancy, tax payments to the state, and the blessing of a judge. That isn’t anything close to what appears to be happening in the Queens cases tied up in court right now.

So while you can’t gain ownership of a house by sneaking in one night when no one is looking, the man in Douglaston Brett Flores, much like the man in Flushing Brian Rodriguez, does seem to be making what appears to be alarming use of housing law. But even that kind of thing is rare. “The idea that New York’s tenant laws enable rampant fraud is just wrong,” says Ellen Davidson, a staff attorney with Legal Aid’s Civil Law Reform unit who has seen thousands of cases make their way through our courts. Though it doesn’t make the exceptions any more pleasant, it does make them outliers. Flores once legally occupied the home as a caretaker for the former owner, who died in January 2023. After that, it seems he just stayed in the house, which means he’s been there for considerably longer than 30 days, the point at which he has certain due-process rights when it comes to trying to evict him. The new owners must evict him in court — even if they say he is lying about having been given permission to stay, and even if he doesn’t have a lease. This doesn’t mean he can’t be evicted — he’s in court right now while the family who bought the house tries to do just that, and his next hearing is scheduled for April. It just may take time. “We all live in a world where there are criminals who sometimes take advantage of situations,” Davidson says of cases that seem to be about scammers. “We’ve seen tons of stories about how people have come in and basically stolen people’s homes through deed theft — it’s a tragedy,” she explains. “But no one’s suggesting that the elderly homeowner whose property was stolen from them should be able to wave a wand and have the thieves go straight to jail and not have to go through a legal, laborious court process.”

In Flushing, at least one of the people involved seems to have a knowledge of housing law that they are similarly using to their advantage. In that example, the men sleeping in Andaloro’s house were initially escorted off the property by police. (One was also arrested.) But one of them, Rodriguez, returned to show police what he said was documentation of work he’d done on the home. The cops present that day, while being filmed by EyeWitness News, decided that was enough proof he was a legal occupant — though it’s not exactly clear why they did that. They told the homeowner, Andaloro, that it was a matter to be settled in housing court, warned her she couldn’t change the locks, and arrested her after she did anyway. Grinthal called that “extraordinary”: “I’ve only ever seen the police actually take action against an owner for a self-help eviction once,” he said. (Meanwhile, in 2023 alone, hundreds of illegal lockouts by owners were reported by tenants in housing court, with only 12 arrests.) Rodriguez implied he knew what he was doing by invoking the courts: “You got to go to court and send me to court,” he told Andaloro. “Pay me the money and I’ll leave or send me to court; it’s that simple.” Creepy? Absolutely. Likely to result in him taking over the house as its legitimate tenant or owner? No.

A housing-court backlog stemming from lack of funding and the pandemic eviction moratoriums means that processing a case of a homeowner — or tenant — in an adverse housing situation like this can indeed take anywhere from months to years. While the case plays out in court, the tenant or licensee gets to stay. (I covered the case of an owner who lived for two years with an unwanted Airbnb guest. It seemed harrowing.) But at scale, New York tenant law protects due process for both parties in a dispute — including the overwhelming number of cases that are called “squatting” but are actually legitimate housing disputes: A tenant who has been evicted but is disputing their landlord’s claims of non-payment; a houseguest, once invited, who overstays their welcome; a pair of roommates who fall out.

Which is why some tenant advocates see a propaganda campaign where anxious homeowners see an epidemic. Landlords in New York have been trying for years to roll back many provisions of the 2019 Housing Stability and Tenant Protections Act, using the argument that it impinged on their property rights. The squatter panic is that same narrative on steroids: Not only do tenants have all the power, but now your property can be “expropriated by a sociopath who quite literally wanders in off the street,” as the New York Post recently put it. These stories, circulating widely and at a fever pitch, “add fuel to the fire,” Sateesh Nori, a former housing lawyer and NYU Law Professor argues. “They say ‘Oh, look what people can do.’”

Even Jake Blumencranz, the state-assembly member from Long Island who proposed a bill this month to address the “squatters wreaking havoc nationwide,” acknowledges there isn’t a whole lot of evidence beyond anecdote that this is an actual crisis. His bill targets cases that are “blatantly schemes,” he said, by extending the 30-day rule to 45 days, and excluding a person with the “intent of squatting” from being treated as a tenant. “It’s hard to see what is squatting and what’s a tendency to squabble,” he told me. Regardless, when I called his office, one of his staffers said that they had been inundated with calls from grateful, terrified constituents.