A male and a female common merganser (North American) or goosander (Eurasian) (Mergus merganser).

A male and a female common merganser (North American) or goosander (Eurasian) (Mergus merganser).

This image was taken by Bengt Nyman. Click here to view Wikimedia source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic License.

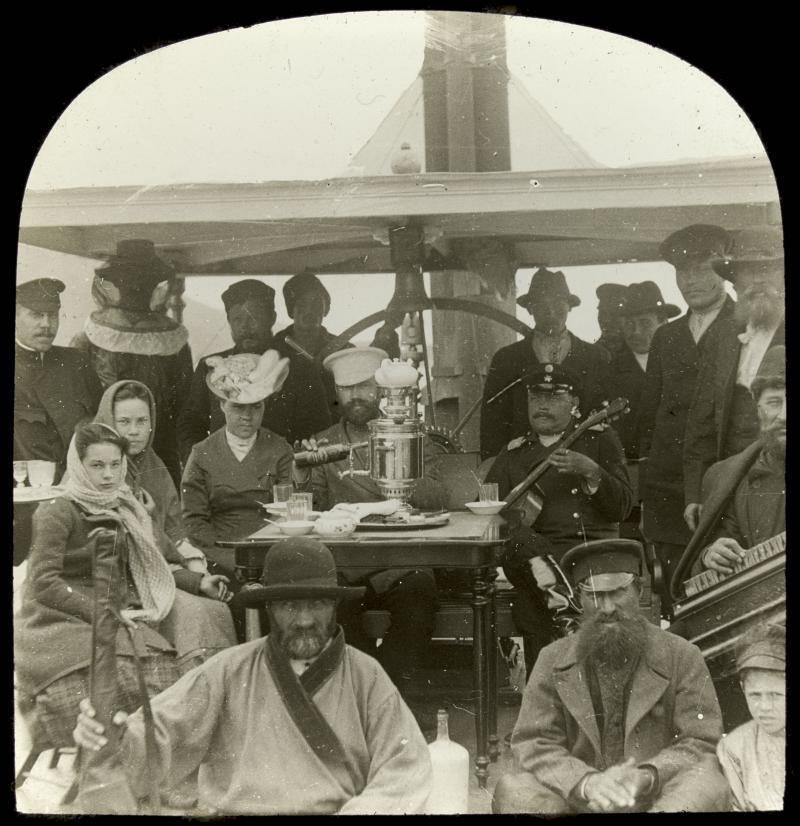

Robert Hall, collector of East Asian birds, in Korea in 1903 with a guide.

Robert Hall, collector of East Asian birds, in Korea in 1903 with a guide.

This image is part of the collection of the Royal Australasian Ornithologists’ Union (RAOU) archives, State Library of Victoria, Australia. The original source is a glass negative and has been digitized. Photo of historical source by Libby Robin.

This work is used by permission of the copyright holder.

It started with a mysterious red-legged diving bird, the common merganser Mergus merganser, which should not have been in Korea in May. The American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) in New York has very few bird specimens from North Korea. This one, AMNH 734284, undated but collected in “Gensan” in 1903, spurred the interest of ornithologists Will Duckworth and Paul Sweet, the latter of whom was the AMNH’s ornithology collections manager. The handwriting on the tag was not that of Robert Hall (1867–1949), the Australian ornithologist and collector whose specimens had been sold to Lord Rothschild in Britain, and then subsequently were purchased by AMNH. Where did it come from and who collected it?

AMNH 734284, as it is known in the museum, was the only common merganser (or goosander) known to have been collected from Korea in May—that is, late enough to be breeding in Korea, rather than just passing through, so technically native to Korea. In the course of my research on the history of ornithology in Australia, I had discovered the story of Robert Hall’s collecting expedition through the voice of his assistant R. E. (Ernie) Trebilcock (1880–1976). Trebilcock, formally trained as a lawyer, was a good naturalist and precise observer, and as he travelled with Hall for 10 months in 1903, he kept a daily diary of his activities for his fiancée Hessie Tymms waiting at home in Australia.

Robert Hall, collector of East Asian birds, director of the Tasmanian Museum (ca. 1912).

Robert Hall, collector of East Asian birds, director of the Tasmanian Museum (ca. 1912).

This image is part of the collection of the Royal Australasian Ornithologists’ Union (RAOU) archives, State Library of Victoria, Australia. The original source is a glass negative and has been digitized. Photo of historical source by Libby Robin.

This work is used by permission of the copyright holder.

Robert Hall was an experienced museum collector, and subsequently a museum director. He discovered that the British Museum’s ornithological collections lacked Siberian shorebirds and accordingly planned a collection trip, which involved traveling, mostly overland, from Melbourne to London via Vladivostok. He calculated (wrongly, it transpired) that he and his assistant could cover the costs of their long and difficult journey by selling the collection of bird specimens to the museum or British collectors on arrival.

The Australian ornithologists followed the extraordinary journey of the “Australian” shorebirds (some of them as tiny as 5–6 grams) that flew to Siberia for two months every year to breed. They travel along what H. Elliot McClure, the head of the United States Army’s Migratory Animal Pathological Survey, later dubbed the “East-Asian Flyway.” Hall knew of this migratory path and wanted to collect birds in breeding plumage: they have much brighter-coloured feathers when they are breeding than when they are in Australia.

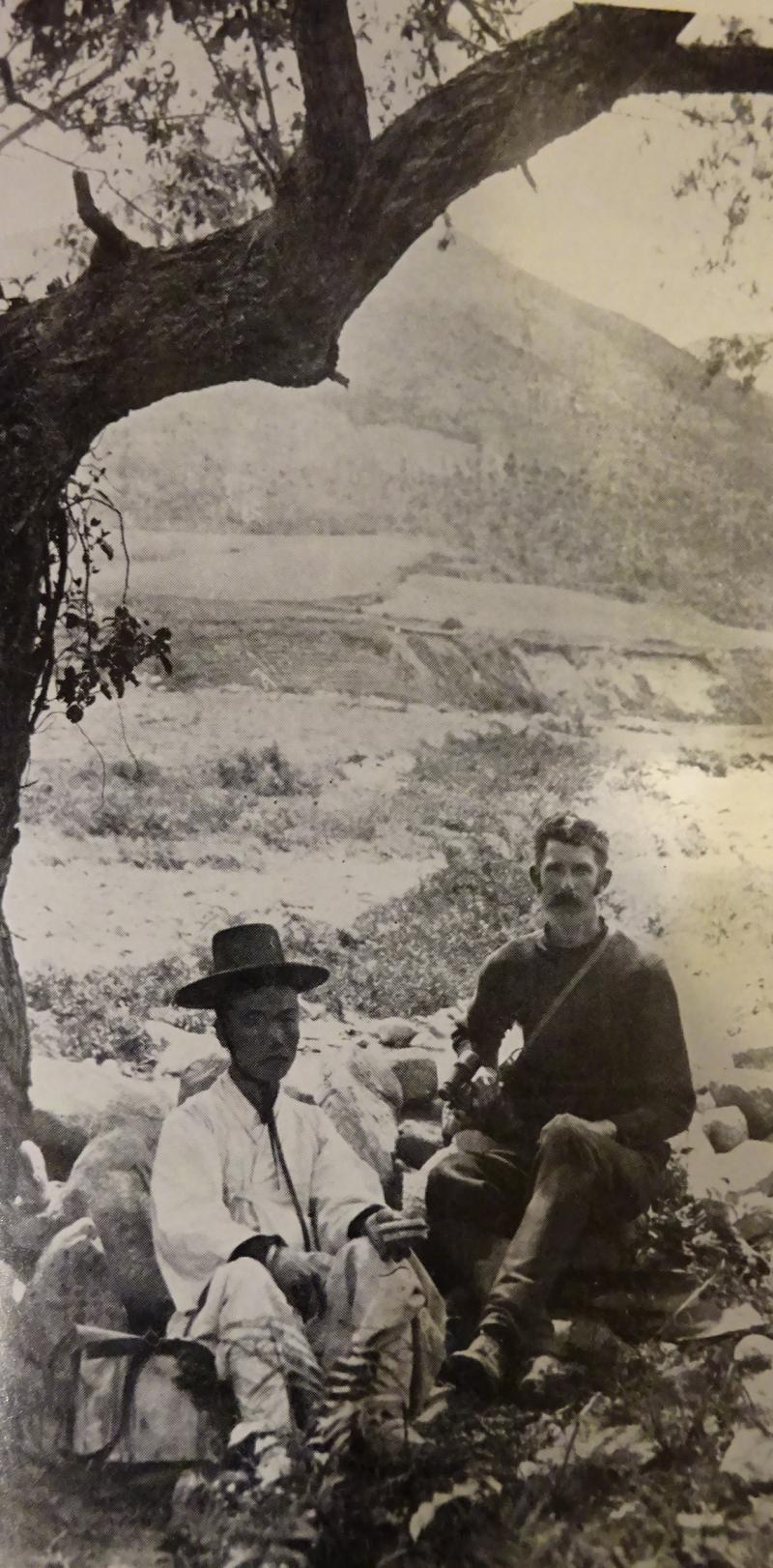

Trebilcock inscribed his name in the Russian diary in Cyrillic characters.

Trebilcock inscribed his name in the Russian diary in Cyrillic characters.

This image is part of the collection of the Royal Australasian Ornithologists’ Union (RAOU) archives, State Library of Victoria, Australia. The original source is a glass negative and has been digitized. Photo of historical source by Libby Robin.

This work is used by permission of the copyright holder.

In 2003, the centenary of the Australian bird collectors’ trip, I worked with a Russian anthropologist, Anna Sirina, and prepared a translation of Trebilcock’s Siberian diary into Russian. Together we mounted an online exhibition about the trip. Anna was excited about the documentary social material from Siberia and used Trebilcock’s letters and photographs for her own work on the social anthropology of the local peoples of Siberia. The Korean story had not been relevant to this, so the Korean letters remained unread until the question of the Korean bird arose a few years later.

Mr R. E. Trebilcock discusses his archives with Royal Australasian Ornithologists’ Union (RAOU) archivist Tess Kloot in 1975, seven decades after his Siberian adventure.

Mr R. E. Trebilcock discusses his archives with Royal Australasian Ornithologists’ Union (RAOU) archivist Tess Kloot in 1975, seven decades after his Siberian adventure.

This image is part of the collection of the Royal Australasian Ornithologists’ Union (RAOU) archives, State Library of Victoria, Australia. The original source is a glass negative and has been digitized. Photo of historical source by Libby Robin.

This work is used by permission of the copyright holder.

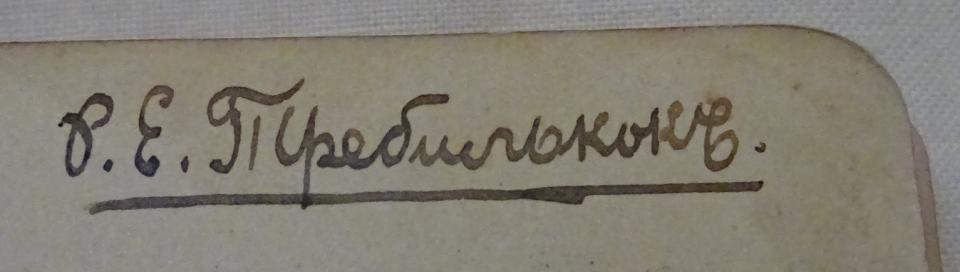

Double page spread from R. E. Trebilcock’s diary, June 1903.

Double page spread from R. E. Trebilcock’s diary, June 1903.

This image is part of the collection of the Royal Australasian Ornithologists’ Union (RAOU) archives, State Library of Victoria, Australia. The original source is a glass negative and has been digitized. Photo of historical source by Libby Robin.

This work is used by permission of the copyright holder.

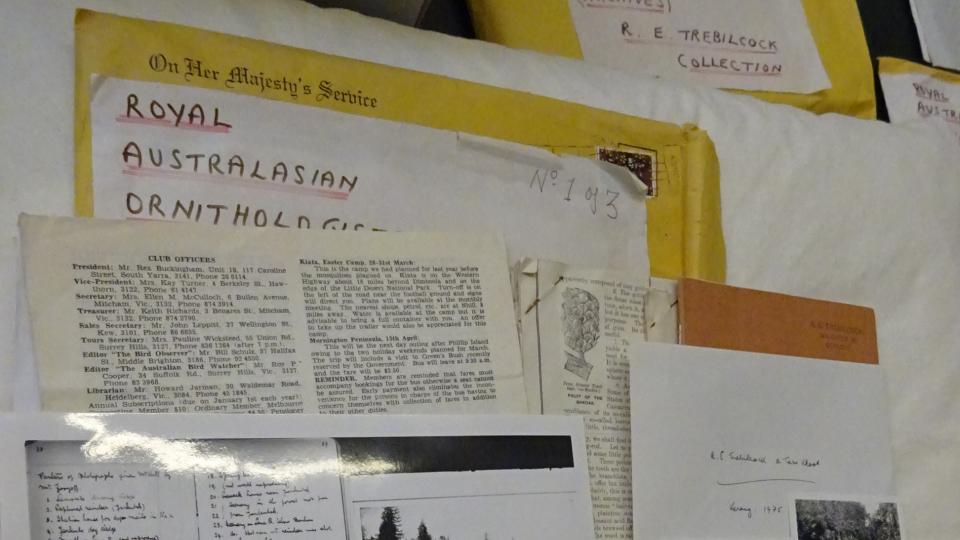

Newspaper cuttings and letters in the Trebilcock collection within the Royal Australasian Ornithologists’ Union (RAOU) archive, now held in the manuscripts collection of the State Library of Victoria.

Newspaper cuttings and letters in the Trebilcock collection within the Royal Australasian Ornithologists’ Union (RAOU) archive, now held in the manuscripts collection of the State Library of Victoria.

This image is part of the collection of the Royal Australasian Ornithologists’ Union (RAOU) archives, State Library of Victoria, Australia. The original source is a glass negative and has been digitized. Photo of historical source by Libby Robin.

This work is used by permission of the copyright holder.

The Korean diary is recorded in letters to Hessie, which were stored with the Siberian diary. The letters are quite personal and detail the many difficulties of arranging travel in Russia.

“Russian authorities look upon us with the greatest suspicion,” Ernie wrote to Hessie.

“Russian authorities look upon us with the greatest suspicion,” Ernie wrote to Hessie.

This image is part of the collection of the Royal Australasian Ornithologists’ Union (RAOU) archives, State Library of Victoria, Australia. The original source is a glass negative and has been digitized. Photo of historical source by Libby Robin.

This work is used by permission of the copyright holder.

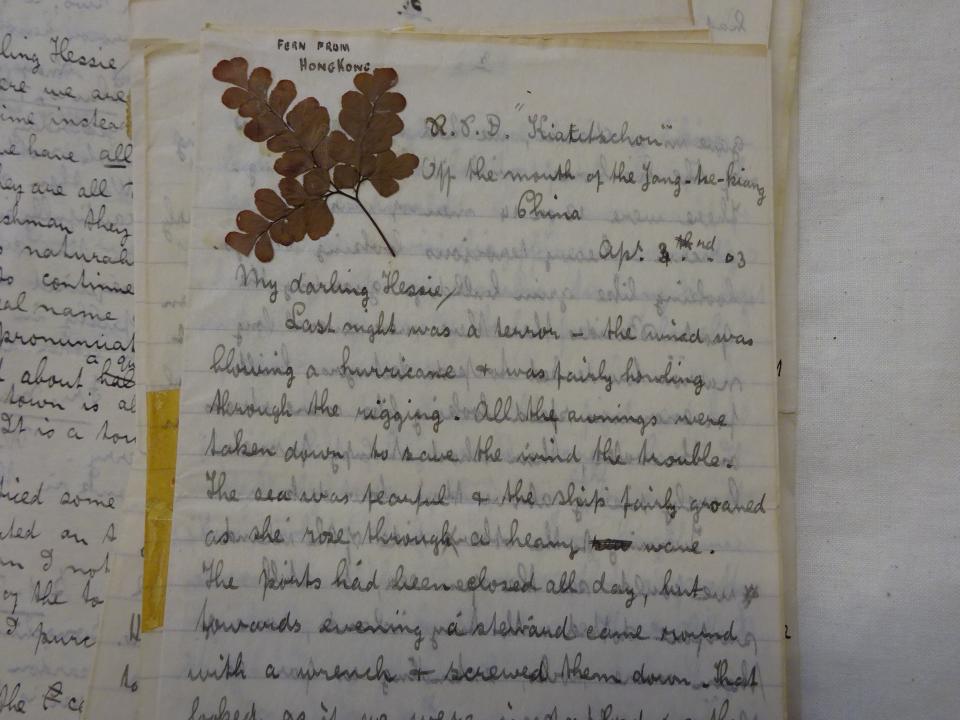

Letters often included souvenirs of his travels.

Letters often included souvenirs of his travels.

This image is part of the collection of the Royal Australasian Ornithologists’ Union (RAOU) archives, State Library of Victoria, Australia. The original source is a glass negative and has been digitized. Photo of historical source by Libby Robin.

This work is used by permission of the copyright holder.

When the AMNH asked about the Korean provenance of their specimen, I returned to the letters that described the sea voyage towards Siberia, via Singapore, Hong Kong, and Korea. The weather in “Corea” was exceptionally stormy. Hall and Trebilcock had tried to depart from Fusan on 21 April, but it was a full week later, on 28 April 1903, that they made it to Wonsan. The Australians were then unable to sail on to Vladivostok until 16 May, because of what Ernie described as a “hurricane.”

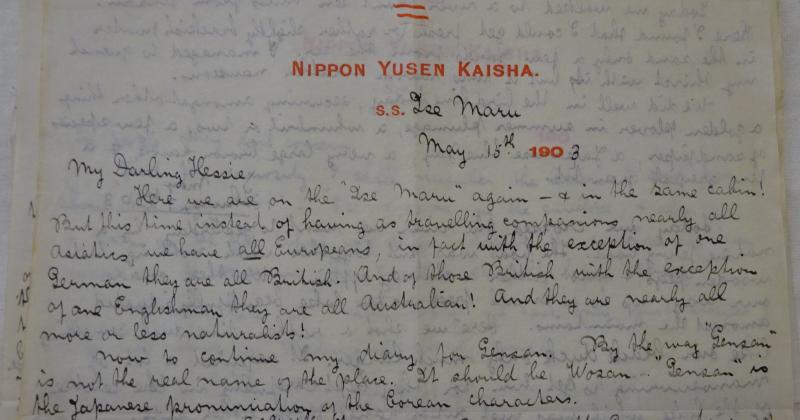

Letter to Hessie describing the passengers on the ship to Vladivostock.

Letter to Hessie describing the passengers on the ship to Vladivostock.

This image is part of the collection of the Royal Australasian Ornithologists’ Union (RAOU) archives, State Library of Victoria, Australia. The original source is a glass negative and has been digitized. Photo of historical source by Libby Robin.

This work is used by permission of the copyright holder.

Whilst in Wonsan, the Australians met members of the English-speaking community, some of whom traveled onwards with them as far as Vladivostok. The local missionary, Mr Foote, acted as Ernie’s interpreter at the post office and Mr Wakefield, the local commissioner for customs lent him a darkroom. Ernie was a good photographer and his glass negatives are an important part of the surviving archive. While the weather in Korea was too stormy to sail, it was an unexpected opportunity to collect extra birds. In his letter to Hessie, Trebilcock recorded that the Korean collection comprised 224 birds of 60 species.

Ernie’s letter to Hessie details collecting forays from Wonsan, including one on 13 May, where they took one bird of a species “new to us,” “a diver with very bright red legs and feet.”

Ernie’s letter to Hessie details collecting forays from Wonsan, including one on 13 May, where they took one bird of a species “new to us,” “a diver with very bright red legs and feet.”

This image is part of the collection of the Royal Australasian Ornithologists’ Union (RAOU) archives, State Library of Victoria, Australia. The original source is a glass negative and has been digitized. Photo of historical source by Libby Robin.

This work is used by permission of the copyright holder.

On the Lena River in Siberia.

On the Lena River in Siberia.

This photo was taken by R. E. Trebilcock and is part of the State Library of Victoria’s digital collection. The permission was granted by the holder of the collection RAOU, which is now Birding Australia. Click here to view State Library of Victoria source.

This work is used by permission of the copyright holder.

Trebilcock’s letters and notes reveal how the documentation of the collection was done later during the long shipboard journeys. Times and even places became fixed retrospectively: it was only later on board ship that he learned that the place he knew as Gensan (the Japanese place name) was also called Wonsan (the local Korean name).

So the mystery merganser was in fact collected in Korea, probably on 13 May 1903 by Trebilcock, for the Hall Collection. It was almost certainly Ernie’s writing on the label. When Paul Sweet and colleagues prepared a definitive list of the Hall Collection from Wonsan, the letter to Hessie confirmed the details on its label. The same hurricane that had created the Australian ornithologists’ collecting opportunity also delayed the bird, explaining why, in 1903, it was still in Korea at a time when it was late enough to breed.

How to cite

Robin, Libby. “The Mystery of the Merganser.” Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia (Summer 2017), no. 22. Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. doi.org/10.5282/rcc/7966 (link is external).

ISSN 2199-3408

Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

2017 Libby Robin

This refers only to the text and does not include any image rights.

Please click on an image to view its individual rights status.

- Hall, Robert. “Through Siberia.” Victorian Geographical Journal XXII Part I (1904): 25–31, with discussion 31–33.

- Robin, Libby. The Flight of the Emu: A Hundred Years of Australian Ornithology 1901–2001. Carlton: Melbourne University Press, 2001.

- Robin, Libby, and Anna Sirina. “One hundred year anniversary of Australian ornithological expedition to Siberia.” Ilin – Historical and Geographical Magazine of Yakutsk, Siberia 3–4 (2003) (issue no. 34–35): 36–44. [Либби Робин, and Анна Сирина. “Путешественник – та же перелетная птица… .” ИЛИН 3–4 (2003): 36–44.]

- Sharland, Michael. “Memories of Robert Hall”. Australian Bird Watcher (September 1978): 222–28.

- Sweet, Paul R., J. W. Duckworth, T. J. Trombone, and Libby Robin. “The Hall Collections of Birds from Wonsan, Central Korea, in Spring 1903.” Forktail 23 (2007): 129–34.

- Trebilcock, R. E. “An Australian in Siberia 1903” [includes biographical material about Trebilcock, and extracts from the letters with the diary]. La Trobe Library Journal 10, no. 38 (Spring 1986): 35–39.

- Whittell, Hubert Massey. The Literature of Australian Birds: A History and a Bibliography of Australian Ornithology. Perth: Paterson Brokensha, 1954.