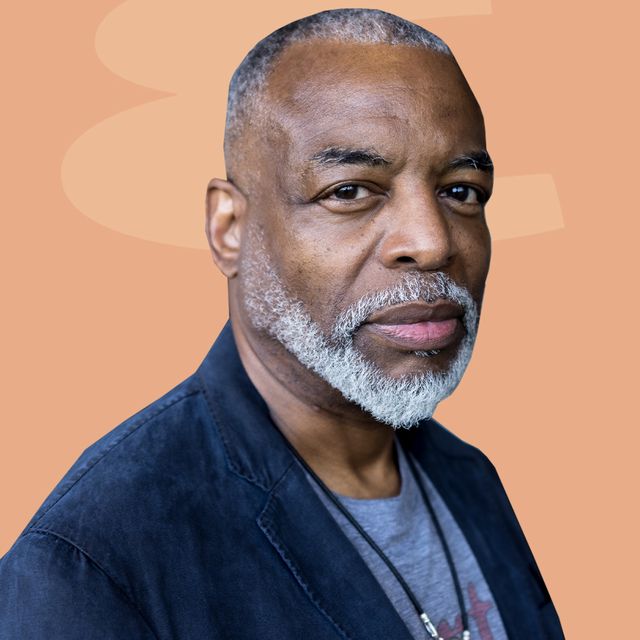

Nearly two decades after PBS’s long-running series went off the air, the Reading Rainbow generation is all grown up. Their love of reading and knowledge is an enduring gift, courtesy of host LeVar Burton and the show’s producers—but in an age of unprecedented assaults on the freedom to read, what’s to become of today’s young readers in the making?

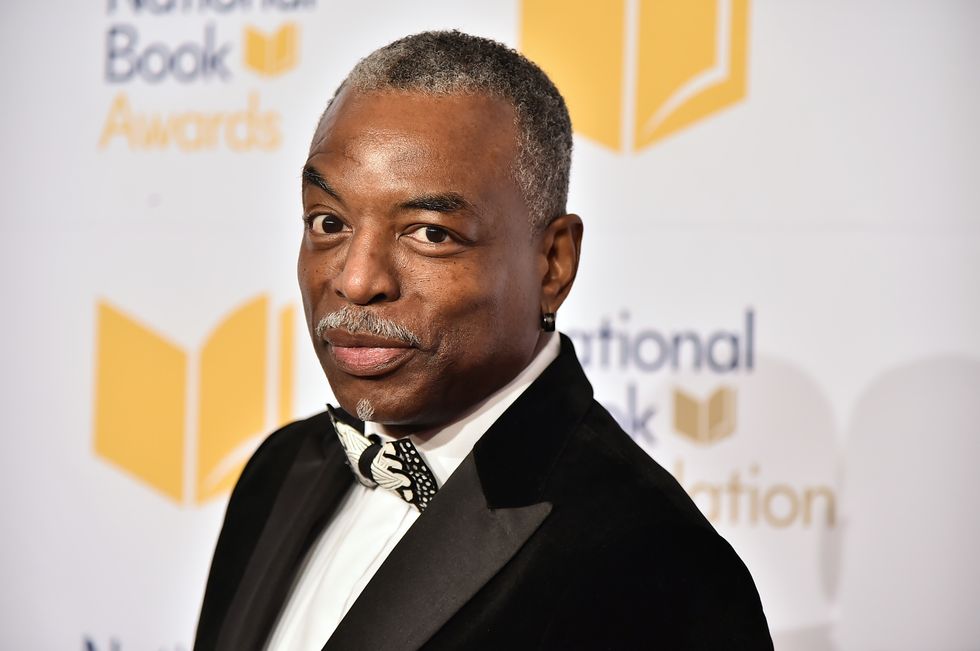

As ever, Burton is looking out for them. The actor and literacy advocate recently served as the honorary chair of Banned Books Week, an annual October event dedicated to raising awareness about attempts to remove reading materials from libraries, schools, and bookstores. Now, he’s making his second appearance as the host of the National Book Awards, where “censorship” will no doubt be the word on every honoree’s lips. “I've put in work in this field; I've put in time on these issues,” Burton told Esquire. “I'm happy to be the face of it and represent it, because these are matters that I care deeply about.”

The cause undoubtedly needs champions. In 2022, the American Library Association documented 1,269 demands to ban books and library resources—the highest number of attempted bans since the ALA began compiling this data over two decades ago. These demands targeted 2,571 unique titles (a 38% increase over the previous year), primarily by and about people of color and LGBTQ+ individuals. According to Burton, “What we're experiencing is a pushback to the idea that everybody's story has value.” Notably, over 87% of Americans oppose book banning.

Just days ahead of the National Book Awards, Burton Zoomed with Esquire from his home in Los Angeles to discuss the freedom to read, the importance of fighting AI, and the books that changed his life. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

ESQUIRE: How does it feel to be heading into your second hosting gig with the National Book Awards?

LEVAR BURTON: I'm looking forward to it. There are some things that I want to talk about in my opening remarks, I can tell you that. For me, being in that room is the Academy Awards for books. For a reader, it's the best room in town.

It's been four years since the first time you hosted. What changes have you observed in the world of books during those years?

The efforts to control what other Americans read and what other people's children read—those efforts have really stepped up in the intervening four years. The whole idea of Americans being in control of their own bodies, their own minds, and their own destinies is a political issue, which is weird, given the fundamental underpinnings of the creation of this nation. But here we are, having this conversation about bodily autonomy, what kids should read, and what we should think. For me, it's a fight worth fighting. It's not only a conversation worth having. It's a fight worth fighting.

Do you see any connections between the battle for the right to read freely and other progressive causes, like the right to make reproductive choices or the right to gender-affirming healthcare? Are these things linked, in the conservative ideology?

They seem to be. When Donald Trump says, "I got rid of Roe v. Wade," he believes that to be true. In fact, he stacked the court, so more than anybody else, he's probably responsible. The fight for reproductive freedom is tied to the effort to ban books. They're definitely linked. What we're looking at is authoritarian control, and that's just not part of the charter.

Are there any banned books that made a strong impression on you as a reader?

The ones that I read as a kid, like Catcher In the Rye and To Kill a Mockingbird, have stuck with me, simply because they occupy a special place in my heart. These are books that are a part of me, so to see them get banned, it feels like someone telling me that I grew up wrong. Like there's something wrong with me for having love for these books. I know that's not true—I know there's nothing wrong with me, and I know that there's nothing wrong with these books. But that's the signal that's sent—that there's shame in loving literature. And that's just a real perverted point of view.

You served as honorary chair of Banned Books Week last month. What was that experience like for you?

It was a blast. MoveOn.org made a T-shirt with my face on it—people love the shirt! The money that's raised with the t-shirt goes to the MoveOn BookMobile, which is a great cause. I've put in work in this field; I've put in time on these issues. I'm happy to be the face of it and represent it, because these are matters that I care deeply about. I'm not of the mind that because of what I do for a living, that I'm enjoined against participating in public discourse. The "shut up and dribble" or "just go act, stupid" mentality doesn't work for me at all. As a citizen of this country, I feel that I have every right to speak out on any issue that I choose. These are issues that I care deeply about.

But I encounter this a lot on social media these days—"because you're an actor, you have no right to an opinion." You know what I really love? I love it when people tweet at me and say, "I used to like you, but now that I know you're woke, we're breaking up." It's like, "Then you really didn't know me, because I've always been this guy." Or the ones who claim to be Star Trek fans, but say I'm too progressive. Do you know who Gene Roddenberry was? Have you ever watched Star Trek? It's wacky, but that's America, and that's Americans.

What keeps you on social media, if this is the kind of feedback you're getting?

I recognize the ubiquitous value of social media for public figures. You just have to have a stiffer spine, these days. You have to tune out the negativity. It's caused me to engage on social media with less frequency—I'm not a daily tweeter anymore. There's so much of it that's toxic, so it's just self-preservation. But I recognize the value of it, and I still try to maintain my voice. I love it for that. That's how I got into Twitter—somebody was impersonating me on Twitter and I didn't think that was right, fair, or appropriate, so I let Twitter know. They made it possible for me to have my name and I thought, As long as I've got it, I might as well use it. That was back in 2007. I was an early adopter to Twitter and I loved the platform, so there's a part of me that's struggling to let go.

In these conversations around banned books, we hear from politicians, parents, and school boards—but we’re not hearing from the young people who are actually suffering because of the decisions adults are making. In all of your advocacy work, do you hear anything from young people affected by book bans?

Here's the thing: I think it's the responsibility of the adults in the room to advocate for those kids. Because in many cases, they don't know what they're missing. And they won't know what they're missing because they won't get it, because these people are in some cases being successful. One of the things I'm most thrilled about is that hardly any candidates backed by Moms for Liberty won their races. There are bright spots, but these are people who would rather children not know the truth. Those kids will never know what they're missing, but it's our job to stand up for them, to be their voices and their advocates. That's what being an elder in this society means to me.

In American politics, it often seems that people try to gain or maintain power by controlling the narrative. Banning books is a very naked attempt to do that. What’s the story that conservatives are trying to tell by banning books?

I wish I knew. There are a lot of stories they're trying to control by banning. We've always had a very tangential relationship with the truth about the nature of how this country was founded, and the harm and damage inflicted in the pursuit of building this nation's greatness. We're in an era now where something in the zeitgeist says, "It's time for everybody to feel seen and heard. That's what we want for our society." What we're experiencing is a pushback to the idea that everybody's story has value—that we're not just this monolithic myth that we've told ourselves we are, as a nation. The real truth is a lot more subtle than that, and it involves a lot more moving parts. The greatness of who we are really needs to be put into the context of the conquest and what it cost. There are people who are opposed to that story being an acknowledged part of who we are. America loves to live in the shadows, but we're living in an age when the truth wants to come out. There's a thirst for the truth that freedom brings, and the resistance to that is the backlash that we're feeling.

Banning books is really just the tip of the iceberg—the next layer down is what conservatives are doing to reframe American history through textbooks.

Why are we so resistant to talking about the horrors of slavery with children? Why? What's the harm of telling them the truth in an age-appropriate manner? This whole conversation about pornographic books in schools is all bullshit. It's lies. It's smoke and mirrors. But it's all done under the guise of protecting children.

For me, it's about being a man who's willing to stand up and speak the truth as I see it. In this society, I've earned the right to speak my piece because I'm here. My genealogy is about to be revealed on Finding Your Roots early next year. The day I did that reveal with Henry Louis Gates and his production company was one of the most important days of my life. Without giving away any of the details, I'll share this much with you: that day changed me irrevocably. What it did for me was give me proof of the notion that I have skin in this game. I have ancestors that were legislators. I have ancestors who started a school in Arkansas. It not only fills me with the swell of pride, but the swell also comes from the flex. When Black people say, "we built this country," that's true. It's not just a phrase—it's a fact. I have the receipts now, so no one will ever be able to look me in the eye and tell me that I don't have the right to speak my piece in this nation.

I can't wait to see that episode.

I'm not the same man I was before.

Thinking about this issue, I was reminded of your documentary, The Right to Read, and its insights into how American education is politicized. Are the banned books panic and the illiteracy crisis linked?

They absolutely are. It's important for everyone to know that school books and how they're published in this country (and what's published in them) runs through the South. Texas buys the most books in the business, and so they have the most sway in a lot of the policy. Where the science of reading is concerned, it's been proven that whole language does not work. We need to talk about why we were so attached to that, and the role that business played in that decision in terms of Lucy Calkins materials—that cozy relationship between her, the publishers, and the school boards who buy the books. We have to be willing to look at it, tell the truth, and dismantle it because it doesn't work. We need to put back in place what we know works: the science of reading. We need to keep politics out of it.

If we really were a society that valued our children as much as we like to say we do, then we would spend a fraction of what we spend on bombs and weapons of war on educating, feeding, clothing, and housing our children. We could make sure that there's no American child who wants. We have the resources; we just don't have the political will. Our idea of who we are belies our actions. If we've proven anything, we've proven that in America, it's business that's the religion. The dollar is communion, and the bottom line is the religious precept. That's what drives policy in this country, these days.

I’d love to talk about how AI is beginning to affect the book world. Earlier this fall, authors were outraged to discover that their work was being used to train generative AI models. Min Jin Lee called it a “theft,” saying, “AI companies stole my work, time, and creativity. They stole my stories. They stole a part of me.” As a writer yourself and as an actor, having just won some strong protections against AI, how does this issue resonate with you?

This is something that we really, really, really need to put some guardrails around. Unchecked, it's clearly more dangerous than not. Even those who are at the inception of popularizing this technology, they're saying, "Whoa, this is moving a lot faster than we ever thought it would." They're saying that we need to be thoughtful about it, and they're right. It's anathema to artists. Theft is exactly what it is. Here in Hollywood, there are background artists who've already been scanned. Those images are being held onto in the event that the studios are able to use them at any given time. One of the things we really fought for in the SAG strike were some controls on how AI is used—not just for performers, but for writers, and for assistant directors who have to make production schedules. We're protecting the jobs of human beings. Over time, we've seen that technology has taken over and caused major shifts in how things get done in our society. But art? That should not be one of them. AI has no soul.

Some authors have filed a copyright infringement lawsuit against OpenAI. What are you hearing from writers and thinkers in your world about how these lawsuits might change the landscape?

These lawsuits have to change things. It's the nature of America—if you want to get anything done, litigate! Sue somebody! I'm laughing, but it's true. These lawsuits are important because they codify best practices and behaviors into law. We have to go through this process.

These are challenging and upsetting times, but where are you finding hope and beauty lately, as a reader and a storyteller?

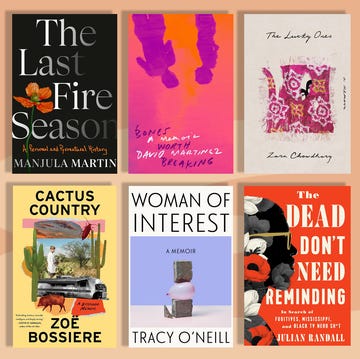

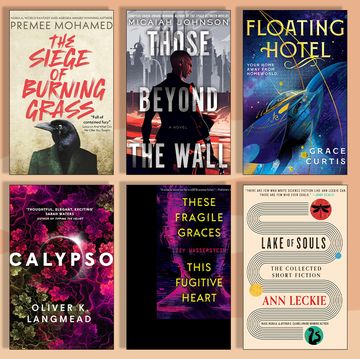

I live for good fiction, and speculative fiction is my favorite genre. It's what I read the most of on my podcast, LeVar Burton Reads. It's what I read for pleasure. I like to live in that imaginative space of "what if?" I like to dream up worlds that are comfortable to me and that make me happy. I like to live in those spaces that are expansive, that are inclusive, that are inspiring. Speculative fiction gives me that.

You're making me think of that episode of Star Trek: Deep Space Nine where Captain Sisko has visions of being a science fiction writer facing racism in the 1950s. There's that memorable monologue where he says, "That future, I created it, and it's real."

You're going to make me cry. That's one of my favorite episodes of Star Trek ever. It's beautiful and it's powerful. Avery [Brooks] is amazing in that episode. It's a great story, impeccably well told.

Well, LeVar, I'm wishing you the best of luck at the National Book Awards.

Last time around, I learned that it's a really rowdy crowd. I was largely successful at getting their attention, but I have a different strategy this time. We'll see how it works. I'm just going to stand up there and wait for everybody to be ready, but I'm not going to try to cajole or shame them into being quiet. I'm just going to wait. Listen up, class.