Look, I know Elton John is not a socialist. He’s an English Knight who pals around with the Royal Family and is said to be worth north of $450 million. And yet, “Burn Down the Mission,” one of his concert staples, a song he’s performed frequently over his nearly 50 years of live shows, can be heard today—at a time when the Democratic Party is espousing worker-party values and rich people are hauled off in irons for bribing their kids into elite schools—as a socialist anthem.

If you’re not familiar with “Burn Down the Mission,” it’s a sprawling pop song from John’s 1970 Tumbleweed Collection in which the hero sets fire to a wealthy person’s home to keep his family alive. “Behind four walls of stone the rich man sleeps,” John sings. “It's time we put the flame torch to their keep.”

The chorus then rings out:

Burn down the mission

If we're gonna stay alive

Watch the black smoke fly to heaven

See the red flame light the sky.

The song is both jubilant and mournful, as the hero who sets the blaze is taken away in front of his wife. “Burn Down the Mission” is now among the 24 songs on John’s setlist for his Farewell Yellow Brick Road Tour, which stopped at Brooklyn’s Barclays Center for two nights last week. He’s transformed the song into a 10-minute extravaganza that brought much of the crowd to its feet. Many of them, I assume, are the very people who might live in that stone house.

I suppose, with this reading of the song, it’s a little weird rising from $250 seats to sing along to “burn dowwwwwn the mission if we’re gonna stay alive.” But it’s also characteristic of John’s music, which is something of a paradox in that it’s both specific enough to evoke a feeling—this song is about socialism—and ambiguous enough to welcome disparate interpretations. Or, at the very least, bring about a visceral feeling of joy.

John didn’t write the lyrics for “Burn Down the Mission.” Bernie Taupin did. In fact, Taupin is responsible for the words behind John’s most iconic ‘70s tracks, from “Your Song” to “Bennie and the Jets.” He would write the lyrics and John would set them to music, sometimes, famously, in a matter of minutes. (A testament to John’s true musical genius.)

That paradox—the specificity and ambiguity—are a core attraction to John’s work from the 1970s, when he had seven No. 1 albums in a row. "Burn Down the Mission," for instance, might not be heard as a socialist anthem in a different era. At the height of the Reagan years, it was probably just a killer pop song. In fact, there's a performance of "Burn Down the Mission" from the Sydney Opera House, where John is decked out in a whig and 18th century costume. The era along with the staging give the tune a whole new meaning.

Again, it comes down to the paradox, the specificity and ambiguity, which allow his listeners to pour whatever feelings they might have into his music—whether it's socialism or, in my case, something far more personal.

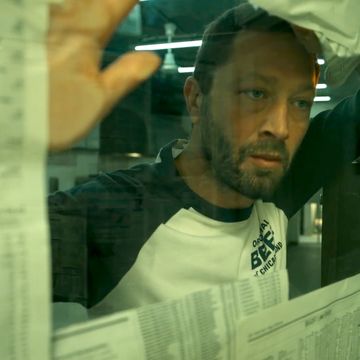

An Elton John album first came into my possession when I was a 14-year-old high-school freshmen, who’d just broken his leg playing football. (I had bargained and cajoled my mom, who was convinced football was a dangerous sport, to let me play. Her instincts were correct.) I say the album, Elton John’s Greatest Hits Volume 2, “came into my possession” because I didn’t buy, borrow, or steal it. The CD just showed up in my collection, and I listened to it in the car with my mom, who drove my hobbled self around the Chicago suburbs—to school, to physical therapy appointments, to football games where I was perched on crutches on the sideline.

Songs like “Levon” and “The Bitch is Back” became the soundtrack for a formative time of my life, when everyone else was listening to “Cotton Eye Joe” and “Roll To Me.” It was an escape for a teenager trapped in a cast, and in his mom’s car. When John played "Levon"—a song Taupin once described as “about a guy who wants to get away from his father’s hold over him”—at Barclays Center I was transported and transcendent. The song is as good played live today as it was in 1995 or, I imagine, in 1971 when it came out.

Twenty-four years later, my leg healed but my mom still mournful that she let me play football, I share Elton John music with my youngest daughter, Elaine, who is five-months old. Somehow, she will only fall asleep to John’s music, usually in my arms. It’s unclear why this happens, or how my wife and I discovered it, but “Someone Saved My Life Tonight” is like a visit from the sandman for Elaine. And now, all these years later, I have a new relationship with John’s music. It belongs to Elaine and me.

And so at Barclays Center, when John played “Someone Saved My Life Tonight,” I was transported to right now, when I rock my daughter to sleep. And the song—which is ostensibly about a man ending a relationship with a woman—is, in my mind, about this tiny little girl saving my life every night.

That kind of intimacy seemed to resonate with the thousands of other people at Barclays, where John, who is now 71 years old, spent hours banging away at his piano, giving the audience a survey of nearly all his hits, while chiming in with stories about his evolution as a person and an artist. (At one point he also called attention to Rami Malek, who was in the audience with his girlfriend, Lucy Boynton, just before dedicating a song to Queen.) At one point, he returned the intimacy by thanking the audience for buying his records, eight-tracks, cassettes, CDs, and concert tickets. John is not an aging rock icon who drags himself on stage, belches out the hits, and collects a paycheck. His live act seems every bit as enjoyable as it might have four decades ago.

Ultimately, it doesn’t matter what any of his songs are actually about. What matters, and John seems to understand this like any great artist, is that the song belongs to the person in the $250 seat, or in the car with his mom, or bouncing around a darkened bedroom with a baby girl in your arms in the wee hours of the morning.