(Editor's Note: This story was first published in April 2013.)

For as long as anyone can remember, Monday night has been Manly Night at the Playboy Mansion. A little after five o'clock, nine or ten of Hugh Hefner's best friends — invited guests, holders of inner-circle memberships that will be good until death — start pulling up outside the front gate. They talk into what looks like a big round rock, and a disembodied voice questions and admits them, sometimes sounding surprised about it—"Oh, hey, you can come up"—and the gate swings open, revealing a hedge-lined driveway and two yellow warning signs: BRAKE FOR ANIMALS and PLAYMATES AT PLAY. The Mansion soon looms at the top of a rise, a Gothic pile with leaded glass windows that overlook immaculate grounds tended by men in green work shirts, each with the familiar white rabbit stitched on the chest. The guests ease up next to a marble fountain topped by a cherub molesting a dolphin, and then they head through the Mansion's thick wood front door and into the appropriately named Great Hall, where there are several large portraits of their host watched over by a full-sized statue of Frankenstein.

Ray Anthony, the ninety-one-year-old trumpeter and bandleader, is usually the first of the men to show up, with either a hat or a toupee on his head. Fred Dryer, the former football player and actor, also arrives, still looking capable of feats of strength, his hands the size of dinner plates. Johnny Crawford, the former child star (The Rifleman) and teen idol ("Cindy's Birthday"), wanders in, as does eighty-four-year-old Keith Hefner, the younger brother and only sibling of the more famous of the Hefner boys. More ordinary men join the gathering as well—a retired kindergarten teacher named Mark Cantor, a movie-memorabilia expert named Ron Borst, a producer named Kevin Burns. The youngest and newest member, Jeremy Arnold, is a film historian and writer. He's been admitted to Manly Night for only a year or so, after spending ten years in the less-exclusive Movie Nights' farm club—Fridays, Saturdays, and Sundays—and he still walks around with a bemused smile, as though he's not quite sure how he ended up here or doesn't believe he has. All these men somehow drifted into Hefner's orbit, and for whatever reason he decided to snare them, the way a planet collects satellites. Now they will never escape his gravity. They will never try.

The center of this particular universe is, for the moment, invisible to the naked eye. He's probably upstairs in his bedroom, where the chances are very high that he's eating a bowl of Lipton chicken-noodle soup, which he eats nearly every day. He rarely eats with the other members of the group, who move to the dining room—a large wood table, a dozen ornate blue chairs, a life-sized cardboard cutout of a smiling Hefner in black silk pajamas, a permanent stand-in—and take their regular seats. There are menus at each place—Hosted by Hugh M. Hefner—but the Mansion is a bit like a cruise ship: The industrial kitchen and its venerable staff (William the executive chef, Brenda the pastry chef, Alan the butler, and maybe six or eight invisible others) will prepare just about any American meal a man could want. Plates of fried chicken soon come out of the shining kitchen, big salads, slabs of rib eye. Cocktails are poured and the men knock on one another and catch up on the week's events and raise a toast they say together: "Gentlemen, gentlemen, be of good cheer, for they are out there, and we are in here."

The late actor Robert Culp wrote those words; he's one of several now-buried members of the Manly Night crew. "I'm pretty sure I'm a replacement of a replacement," Arnold says, his smile still stuck to his face. Mel Tormé, John Dante, Don Adams, Jerry Vale ("He's not dead; he just moved away"): Each of them sat in these same blue chairs and said the same toast every Monday night until one Monday they didn't. Hefner, who will turn eighty-seven in April, has loved and survived generations of friends, but he doesn't like, or need, to be reminded of their departure. One week they disappeared, and the empty spaces around the table were filled just as quickly, like infantry.

At last, here's Hef. His three-dimensional human self is, in fact, also wearing black silk pajamas—these are his public pajamas; his sleeping pajamas, at least in winter, are flannel—and his slightly thinning hair is combed neatly into place. He moves slowly, on account of his bad hip, but a buzz still radiates off him, like a kid up to no good. He takes his seat at the head of the table, a folder and notepad in his hands. He opens them up, nodding his greetings, and now Manly Night becomes a more serious business. Every week, the men nominate the movies they want to see. They are often vestiges of precode Hollywood but not always. Nominations carry over week to week, and new nominations must be seconded, Keith Hef-ner relaying the various titles into his brother's good ear and Hefner keeping careful records of it all in pencil, with big, angular script. Then the men vote.

Hefner reads out this week's nominees: Me and My Gal (1932); Stardust Memories (1980); Road House (1948)—"I love Richard Widmark!" Fred Dryer lights up—Where the Sidewalk Ends (1950); Phantom Lady (1944); Private Number (1936). After a tense round of voting and a tiebreaker, Where the Sidewalk Ends, a film noir starring Dana Andrews and Gene Tierney, wins by the narrowest margin. Hef-ner scoots off back upstairs to pass the results to John the projectionist (sixty-one years old, he has worked for Hefner since he was a teenager, another trapped meteor), and the rest of the men continue with their dinner, their laughter echoing off the oak-paneled walls.

Some nights are more eventful than others. One-time guest Mike Tyson made a particularly lasting impression. As the regulars remember it, he caused a stir within minutes of his arrival by smoking inside. (The Mansion is now strictly smoke-free.) Later, when the movie started, Tyson dropped into one of the big leather couches and fell asleep shortly after the opening credits. It wasn't long before a cell phone rang out in the darkness. A ringing cell phone during a movie at the Mansion is a first-order violation; that's the sort of offense that can lead to permanent exile. The men looked wide-eyed at each other—who would dare?—before they realized it was Tyson's phone that was ringing. He slept through it. Then it rang again. He stayed asleep. Tyson's phone rang and rang throughout the movie, and he didn't move once to answer it. Nobody else moved, either. They were all too scared to wake him.

On another night, Bettie Page was invited to come see, for the first time, The Notorious Bettie Page, a 2005 biopic starring Gretchen Mol as the early, iconic Playmate. In her eighties then and still getting used to the idea of her late-life revival, Page sat near the back of the room. Everybody hoped that she liked what she saw. (Hefner was especially protective of her, having loudly denounced a biography that documented her battles with mental illness and occasional violence. A giant topless photograph of her still hangs in the hallway upstairs.) Those hopes were shattered only minutes into the movie when Page began screaming at the top of her lungs: "Lies! Lies! Lies!" Then she burst into tears, her face in her hands. "Why can't they just tell the truth?" she said between sobs.

But the only drama on this Manly Night comes when John can't find Where the Sidewalk Ends in Hefner's enormous collection of movies, rows and rows of shelves filled with gray VHS boxes and white DVD cases. (There are more than a thousand DVDs stacked and shelved in Hefner's bedroom, and these aren't even part of the official library.) There is momentary confusion, because half of these men can't hear very well anymore—"The word you'll hear the most tonight is What?" Borst cracks—and none of them can believe that Hefner's collection has a hole in it. Hefner seems genuinely flustered, as though he's suddenly learned something unpleasant about himself, but soon John emerges triumphant from some corner of the Mansion, and Hefner's existential crisis is averted. At precisely 6:30, he says, "Shall we go watch a movie?" He says it as though the idea has just struck him, as though he were making a suggestion, even though he's had exactly the same idea at precisely 6:30 every Monday night for decades, and the men put down their forks, some of them midbite, and head back through the Great Hall and into the living room.

Now that movies are shown there four nights a week—five, actually, Thursday night recently having been designated James Bond Night—the living room is close to a full-time theater. (Tuesday night is Game Night, during which the Hefners and assorted fantasy women play Uno or Mexican Train.) There is a grand piano and the sort of stone fireplace that a different man might stare into, but everything else in the room is directed toward the far wall, filled with a huge white screen. There are couches and rows of chairs aimed at it, along with piles of crimson cushions that can be wedged behind decrepit backs. Most of the men have ducked into the kitchen at some point to place dessert orders, and slices of chocolate cake and apple pie appear, armfuls of Häagen-Dazs bars and towering ice cream sundaes. The lights go out, and the men tuck into their sweets and watch a short clip of long-ago jazz, applauding at the finish, before Where the Sidewalk Ends begins and their world is black-and-white again.

Hefner sits where he has always sat, on the couch closest to the screen, with Ray Anthony beside him and his brother behind him, routines so embedded they feel like breathing to them. He pulls a blanket over himself, and the red light from his headphones shines through the dark, and he is relaxed now, smiling, lost in a movie he has already seen however many times. Watching Hugh Hefner watch a movie is like watching another man look out to sea. When he and Keith were boys, they would go to the Chicago theaters three or four times a week, double features, and they would sit in the blackness and together go far away. "In that darkened theater," Hefner says, "all things were possible."

Where the Sidewalk Ends is good, fatalistic, classic noir. At one point, one of the characters says of another, "He grabs himself a dizzy blond once in a while, but that's no life," and the men burst into knowing laughter. It seems as though Hefner's missed the joke, left out of range by the movie and his headphones, but he lifts himself out of the couch a little and turns around, his face lit white, his shadow on the screen. "Oh, yeah?" he bellows, and now the men laugh harder. Later, after Hefner has said goodnight to his friends, they will linger and talk about how lucky they are, how much Manly Night has come to mean to them, sharing one another's company and former loves, this group of deaf and silver men sitting in the dark, eating ice cream sundaes, living out the dreams of boys.

Because nothing here changes — because even when the rugs and carpets are worn through, the replacements are perfect replicas; because the Game House is stocked with Donkey Kong and Centipede and Defender; because there are mysterious big-buttoned panels throughout the house that were once the height of technology and today look as though they've been ripped out of Soyuz capsules; because the women who drift through here like specters still look as though they've been peeled off the hulls of World War II bombers; and because the movies are still in black-and-white — it can feel as though nothing will ever change, that all of this will last forever. But even in this surreal place, where the years matter less than they do on just about any other settled acre in America, the outside world has begun to push its way through the gates. Illusion still maintains permanent residency at the Playboy Mansion, but for the first time since Hefner bought this place in 1971, truth has lately been paying visits.

Sometimes the traces of its presence are subtle. In the backyard, currently patrolled by a pair of hostile crotch-hunting African-crowned cranes named Spot and Carl, a small gravestone has been set into the grass: TERI, BELOVED WOOLLY MONKEY it reads. (There are still lots of other living monkeys here, mostly squirrels and spiders dancing in their cages, because why visit a zoo when you can build one in your backyard?)

Other times, the warning signs are found in small but significant changes to long-standing patterns of behavior. Mary O'Connor, for instance—who is eighty-four years old and has worked for Hefner for fully half of those years as his house manager and "office wife"—has said that she would like to be interviewed for this story. That fact alone is enough to spark sad whispers among some of the Mansion's sixty or seventy full-time employees. O'Connor has rarely spoken of Hefner and her time with him, but this most faithful ally in this army of faithful has been fighting cancer, and it appears she might have some things she'd like to say before it is too late.

And then there are truth's more cruel and obvious signs, in bad hips and ears. This week, Hefner has been especially suffering because he had two teeth extracted, and the holes left behind have become infected. He's been in serious pain, and despite his putting on a valiant appearance of business as usual, the hurt is telling on him. It has left him close to sleepless—he's never been a great sleeper, but he's been up for most of several nights—and the people who love him are worried about him.

Even when Hefner does manage to sleep, he doesn't dream much anymore. He is that rare man without fantasies. He has lived the life he wanted to live, inside a world that he has built to his exacting and permanent specifications. He talks sometimes about the "remaining years," but not in the way most of us speak about them, with vague notions of unfinished business and aspirations. His only hope is that nothing else changes. "I want the rest of my life to be very much like it is now," Hefner says. "I want it to be like this." The rigid schedules and routines, the tight circle of familiar friends, the time capsule that is the Mansion and the movies — all of it is designed to help him resist the relentless forces that overtake other men. Having achieved his vision of perfection, Hefner's last fight is the fight to maintain it.

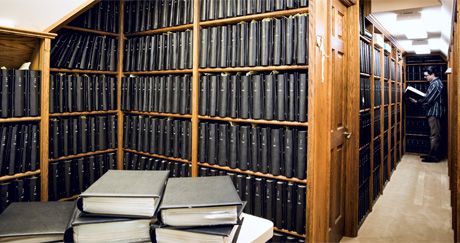

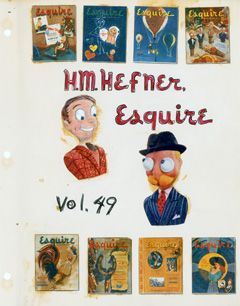

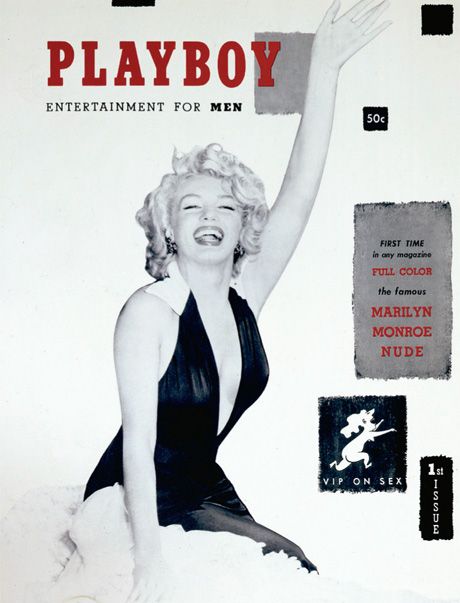

He holds two Guinness World Records, for different kinds of devotion. The certificates are on display not far from Bettie Page's beautiful tits. He is the longest serving editor in chief of a magazine—Playboy's first issue came out in December 1953 (he founded it after leaving his job as a copywriter at Esquire), with a sixtieth-anniversary issue planned for the end of this year—and he has the world's largest collection of personal scrapbooks. A genial but intense forty-nine-year-old man named Steve Martinez oversees their assembly and upkeep; he has a silver tooth and dark-framed glasses. For twenty-two years, he has been Hefner's full-time archivist, responsible for the thick black books—2,643 volumes and counting—that document virtually every day of Hefner's long and eventful life. Apparently, Elvis Presley kept, and Carol Burnett currently keeps, an impressive scrapbook collection, but nobody has more completely self-documented his own existence than Hefner.

Dick Rosenzweig, seventy-seven now, has been Hefner's most trusted business lieutenant for fifty-four years; in the movie of Hef-ner's life, Rosenzweig will be played by Robert Duvall. One afternoon at the Mansion, he tells an insane story about the time he, Hef-ner, Hefner's then-girlfriend Barbi Benton, and Gene Siskel, in the role of documentarian, flew on the Big Bunny, Hefner's black disco-equipped jet, to London to rescue Playboy's floundering film production of Macbeth, directed by Roman Polanski. Rosenzweig guesses this all happened in 1970 or 1971, or thereabouts. Even back then, Hefner never really liked to travel, but after figuring out how to keep the cameras rolling, he decided everybody should go to St.-Tropez for a bit of sunshine. It would do them all good. So, Rosenzweig recalls, off they jetted to the South of France, where Hefner rented a yacht and women fell out of the sky, including a Scandinavian amazon who never wore more than a pair of bikini bottoms and sometimes not even those. "It was really a remarkable scene," Rosenzweig says, which is something for him to say.

Back upstairs in the scrapbook room, Martinez nods and pulls one of the books off the shelf. During the week, typically, Martinez collects photos and clippings and other material for the scrapbooks, and on Saturdays Hefner puts the books together and writes captions. (They are still typewritten with the same typewriter wheel so that the font will remain consistent from beginning to end.) New sets of photos always start on the right-hand page, almost like chapters. "There is a system," Martinez says. Now the system has yielded that trip to London and St.-Tropez—or trips, in fact. We can see the trip to save Macbeth happened in February 1971; the trip to St.-Tropez was to celebrate the film's finish, and it began precisely on August 8 of that year. Rosenzweig must have been mistaken in his recollection, because memories are fallible and the scrapbooks are never wrong. In any case, there's Polanski with his shaggy hair, and there's Siskel looking bewildered, and there's Hefner playing backgammon on the yacht—the Tracinda Jean—and there's Barbi Benton looking deliriously beautiful, and holy fucking shit, there's the Scandinavian amazon with her long blond hair and her enormous sun-drenched Scandinavian amazon boobs.

Over time, Hefner's self-accounting has become even more detailed. The earliest single volumes, which are remarkable—featuring Hefner's childhood cartoons and report cards; a picture of Hef-ner as a baby with the caption "Our hero at six months in his first formal portrait"; the receipt he gave his mother, Grace Hefner, for her $1,000 investment in Playboy—might document a few months or even a year. Later volumes might capture only a single month. Today's volumes span only three or four days. So every Saturday, without fail, Hefner comes up here and sits down at the desk next to the little oval window, puts on some Bing Crosby or Frank Sinatra, and fills a few dozen more plastic sleeves while Martinez works away beside him, collecting captions, double-checking the order of things.

"The most important thing is the date," Martinez says. "If you have the date, then you have everything."

Martinez is about three months behind in his work. Hefner likes to wait for even the farthest-flung clippings to arrive in the mail so that there will be no loose ends or missing links, no late additions that force him to start a new set of photos on the left-hand page. (Around the world, Playboy still gets something like a billion press impressions every month; by the company's measure, 97 percent of the people on earth have heard of it, ranking the brand up there with Nike and Coke.) The little office is cramped with fat folders and boxes stuffed with photographs and scribbled notes and correspondence, all waiting until the collections are deemed by Martinez to be whole and Hefner is ready with his next bundle of plastic sleeves.

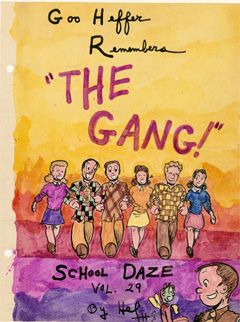

Hefner can't fully explain why he has kept the scrapbooks. The simplest answer is that he has continued to do so because he once did, and he believes that every start should have a finish. But he also sees the scrapbooks as a kind of foundation for everything else he has done. If he had not been the sort of person to keep scrapbooks, he wouldn't have been the sort of person to start a magazine, or at least not a magazine like Playboy. "It's all kind of interconnected," he says. "The magazine is a professional version of the same thing." In Playboy, Hefner is the central character of a sixty-year story, our guide to his definition of the good and well-lived life. In the scrapbooks, Hefner is sometimes more literally a character—such as in his high-school-era cartoon autobiography, School Daze, in which he refers to himself as Goo Heffer—but in them he is also the guide to his actual life. That it happens to look very much like the life he led in the pages of Playboy shows only how committed he was to the cause. This preacher practiced.

Today, however, the scrapbooks serve another, perhaps accidental purpose. Hefner doesn't look much at his collection—he spent ten years working on an autobiography before abandoning the project, realizing that he'd already written it—but whenever he does, virtually every minute of his life is poised to rush back to him at once. It's like having complete and indexed access to a man's entire memory bank. For a visitor, flipping through these pages is a dizzying experience; for Hef-ner, it's vertigo.

One of the most disorienting features of a disease like Alzheimer's is that its sufferers lose all sense of time. Sometimes they are old and sometimes they are young; sometimes they are who they were as parents or grandparents and sometimes they are who they were as children. They lose the ability to separate their own lives and the lives of others into anything like phases. Hugh Hefner does not have Alzheimer's. His brain remains sharp; almost every afternoon, he pulls fat red pencils out of the cup on his desk and edits the pages of his magazine. But up here, surrounded by his scrapbooks, he is everything he has ever been all at once, and today is every day he has ever lived.

Late on manly night, after most of Hefner's friends have finally gone home, he appears at the top of the grand staircase that tumbles down into the Great Hall. He is wearing pale-blue flannel pajamas now, his winter sleeping pajamas, and his hair is no longer so neatly in place. He had eaten his dinner late, in bed, where he takes most of his meals, ordering them from the kitchen by number. There are very few things he will eat, most of them the same meals his mother made for him when he was a boy. Lately, he has been calling down for the number 6: "A BLT," he says. "With chips, milk, applesauce. And a blond." In the kitchen, there are photographs of each of his trays so that they can be replicated exactly each time out. The chips on the side are carefully selected by the chefs, fully formed and unbroken. (If Hefner has crackers with his soup, they must all be uniformly white and sharp-cornered.) Today's blond is similarly flawless, twenty-six-year-old Crystal Harris, a former Playmate who, only a few weeks ago, on New Year's Eve, became the third Mrs. Hefner.

Only when it comes to women does his otherwise perfect accounting fail him. The wives, of course, he knows: First was Millie, long ago, with whom he had two children, sixty-year-old Christie and fifty-seven-year-old David; next came Playmate Kimberley Conrad, with whom he had two more children, twenty-two-year-old Marston and twenty-one-year-old Cooper; and now Crystal Harris. But the women in between, the girlfriends and Bunnies and aspirants and Scandinavian amazons in St.-Tropez, they blur into a kind of glorious mental hurricane. It is the only question that stumps him: How many women? "How could I possibly know?" he says. "Over a thousand, I'm sure. There were chunks of my life when I was married, and when I was married I never cheated. But I made up for it when I wasn't married. You have to keep your hand in."

Hefner and Crystal were to be married once before, in 2011. (They first met in 2008, when she came to Hefner's infamous Halloween party dressed as a French maid. There are, of course, photographs of the encounter in a scrapbook.) The July 2011 issue of Playboy featured Crystal on the cover, with a pipe and Hefner's smoking jacket slung over her shoulders, and the cover line: "America's Princess. Introducing Mrs. Crystal Hefner." Then she changed her mind. Red stickers were hastily applied to each copy— RUNAWAY BRIDE— and much ugliness followed. Crystal told Howard Stern some not very nice things about Hefner and their sex life; Hefner alternated between his brave public face and private sadness. Crystal had given Hefner a sculpture, strangely chaste, of the two of them sitting on a bench, young love courting. It had sat in pride of place, on a sideboard in the dining room. After her departure from the Mansion, the sculpture, too, disappeared. But Hefner left a large portrait of him and Crystal, painted by former Playmate Victoria Fuller, hanging by the front door. It was never touched.Something similar happened with Kimberley Conrad. (During one dreaded, inevitable Movie Night, Citizen Kane played out on the screen. Hefner sat in his usual seat, with Conrad nestled beside him, and everybody else did their best to ignore the parallels. That was until the tarty Susan Alexander came into view and Conrad raised her hand and said, "That's me!") Even after they split up, when Hef-ner bought Conrad the mansion next door and smashed down the wall between them, he kept a blown-up version of her centerfold on the wall in his library. It wasn't until Marston and Cooper told an interviewer that they didn't love seeing their mom's bush every time they came over that it even dawned on Hefner to take it down. Today, Conrad's portrait sits on the floor in his office, leaning against a wall, piles of loose paper and magazines and books slowly rising around her, now as high as her thighs. He doesn't throw out much anyway, but he will never be able to get rid of that picture, because Hugh Hefner wears his heartbreaks like a teenage girl.

He doesn't just love women; he worships women. He can remember in painful, intricate detail the rejection that gave birth to his idolatry and the man he is today. (He has never understood the accusations of sexism made against him. "The women's movement kind of came out of left field in the 1960s and 1970s when they turned on Playboy," he says. "They were allies as far as I was concerned. How could they miss the point?") The popular high school girls held a hayride every year, and Hefner was in full crush with a "perky brunette" named Betty Conklin. She, however, had eyes for one of Hef-ner's best friends, Bob Hogan, and it was Hogan, not Hefner, who ended up riding the hay. "And I thought, Shit. And I changed—probably in those days I didn't think Shit—but I literally changed my style," Hefner says. He never again introduced himself as Hugh, and he started dressing better, and he became obsessed with the latest gadgets and objects of prestige, with lifestyle before it was even a word. He never again wanted to be part of a collection, only a collector—always the host, never the guest. Even today, he will rarely go to someone else's party. His Manly Night friends once hired a cameraman to film the insides of their houses, and they took Hefner on a makeshift tour one Monday night by movie light so that he could at least see they had homes to go to, even if they were always at his.

It was in their macho bravura that Hefner found solace when Crystal bolted. "If I ever try to get married again, shoot me," he told them before they watched another movie, and he seemed to mean it. When Crystal did come back, the men talked to one another—Should we say something? Should we stop this? His brother waved them off. "He's happy," Keith Hefner says today. "Let him be happy."

The younger Hefner is a smiling, buoyant presence, and he spends six nights a week at the Mansion, playing his customary role of benevolent force for good. "He's probably my best friend," Hugh Hefner says. He was one of the original investors in his brother's magazine, and that worked out pretty well for him. He was an actor and later, for most of the 1960s, he recruited and trained Bunnies for Playboy's chain of clubs. He had nearly as much sex as his brother did. "Can you imagine being number two to him?" Keith says. "Good deal." Hugh Hefner can sometimes make it hard to distinguish between the man and the brand, who he is and who he thinks we want or need him to be, but Keith bears none of those burdens, and one day he sits in his brother's library, unencumbered by anything other than his lifelong desire to be helpful, and he is asked: Why movies?

"Our mother took us very early to movies," he begins to answer in his rich, strong baritone. "We loved it. It was a great escape. I think so much of it … the dreams …" He stops, searching, before he begins: "The lack of warmth and affection in our home had a tremendous impact on both of us. There was no hugging and kissing. Our mother and father were religious and strong and good puritans. I can remember as a young teenager, I was going over to pick up my buddy at his home and we were going to go wherever we were going. His mother came out on the stoop and she hugged him." And now Keith's voice falters. He is crying at the memory of a friend's hug from his mother, more than seventy years ago. "That's what we didn't have," he says finally. "That's why movies."

And that's why Keith told the Manly Night crew, "Let him be happy." Nobody pretends that the marriage of Crystal and Hefner is a marriage of white-hot passion. It's a marriage of comfort and security, not just for her, but for him, too—maybe even more for him than for her. Crystal laughs easily. She wears pink track pants a lot, tucked into a battered pair of Uggs. If Hefner is sitting in a room and she walks in, he hops up and gives her a kiss on the cheek; he watches her talk; he makes little gestures with his hands, rubbing the tips of his fingers together, asking her to put her hand in his. "He believes in love," she says. "Hef loves me more than anybody else in a relationship ever has. It took me time away to realize that. I think I realized that here is where I'm meant to be."

"All our friends think it's made in heaven," Hefner says. "It's only people who don't know us, who simply see us as stereotypes in terms of age and beauty… I just feel very, very fortunate to have found her at this stage in my life. I saved the best till last."

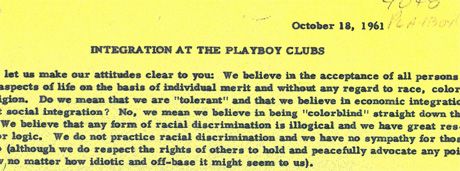

One of the defining aspects of life at the Mansion is that in its ignorance of time, it must also ignore age. At every party, at even the smallest gathering, there are men and women from both ends of the spectrum, virtual teenagers and ancients, meeting in some happy middle. Hefner introduces Crystal to Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers movies or the lost celebrities in his scrapbooks; she introduces him to True Blood ("He'll be like, Boobs, I like this scene," Crystal says) or Twitter. "Ageism is a variation of racism or sexism, all the other isms," Hefner says. In his scrapbooks, there is a remarkable in-house memo he wrote on October 18, 1961, when Playboy Club franchises in Miami and New Orleans refused to admit African American key holders and he bought the clubs back. "This is to say that we are outspoken foes of segregation," the memo reads, "that we believe in brotherhood as a matter of practice and that we are actively involved in the fight to see the end of all racial inequalities in our time." For years he was ahead of the culture, and today, in his house, under his roof, nobody will be written off because of the number of years they have or have not yet lived. Neither experience nor inexperience will be considered a sin. Nobody here will be judged by such uncontrollable things.Now Hefner comes down into the Great Hall, his black slippers careful on the stairs. He is carrying a photo under his arm in a silver frame. He walks wordlessly to the table that stands near the front door, under that Victoria Fuller portrait that never left the wall. (The bench sculpture has since reappeared in the dining room.) It is a picture from his wedding night. He is wearing a tuxedo; his arm is around Crystal; their dog, Charlie, who is also wearing a tuxedo, is in her arms. Hefner looks at the photograph, sets it on the table, adjusts it just a little, and smiles. "I'm essentially a romantic," he will say later, "always have been," but tonight he stays quiet, as though he were somehow alone in a house in which he has never spent a single minute alone.

One day Steve Martinez will be by himself in that little room upstairs. He will put on some music, Bing Crosby or Frank Sinatra, and he will need to finish the three or four months of scrapbooks that will have been left incomplete — he will be the one who will have to abide by the system, writing the captions and filling the plastic sleeves — and then he will have to open envelope after envelope containing obituary after obituary, loud celebrations and petty condemnations of the man whose life he has helped chronicle for twenty-two years. Hefner has told him more than once that he'd like the obituaries to fill the last scrapbooks, and that will be it. Martinez usually changes the subject. "I don't really like to think about that," he says of the prospect of finishing Hefner's life without Hef-ner. "That's not a very nice thing to think about."

And yet Hefner has thought plenty about it. He paid a lot of money many years ago for the vault beside Marilyn Monroe's, at Westwood Village Memorial Park Cemetery, not far from the Mansion. He likes the idea of his life's story ending with him lying next to his beloved first centerfold. "I connect to that sort of symmetry and continuity," he says. "Things fitting together. Making sense." Johnny Carson once joked that for the money Hefner had paid, he should at least have ended up on top of her. ("Johnny Carson said that, not me," he is quick to point out, because some people are sacred.) He does not believe in an afterlife—"No, this is what you get," he says—but he does believe in strong finishes, in monuments and legacies. It says something about a man who so doggedly fights a fight he knows he will one day lose—a fight that he is already losing in some ways, round by relentless round.

On January 27, Mary O'Connor dies. She had been sick, but her death is still a terrible shock. Stunned is the word that people at the Mansion use. The end came so quickly; she was winning and then suddenly she did not. She never had the chance to tell the stories she wanted to tell about the man she knew so well, or simply to say whatever it was she wanted to say. Crystal, who had grown very close to O'Connor, visited her the day before in the hospital. A devastated Hefner had not. He takes to Twitter to pass on the sad news: "We loved her more than words can say," he writes. This time there is no replacement, no substitute, no Jeremy Arnold waiting in the wings. For some people, there is no succession plan. They just leave, and there's no getting over it.

Reality continues to assert itself in other ways, too. There have been dramatic structural changes at Playboy Enterprises in recent years that have been both essential and painful. The 2008 recession, combined with tectonic shifts in the publishing industry, nearly saw Playboy go under. The company's stock plummeted—it had gone public in 1971—and the New York Stock Exchange threatened to delist it. Circulation of the magazine collapsed to 1.5 million from its peak of more than 7 million in the 1970s. The clubs had long since been closed. Christie Hefner, who had taken over as CEO in 1988, finally resigned in December 2008, having reached her personal limit. "I had run out of things I could do for the company," she says today. "There's this expression in business, 'Don't bet the ranch.' Our equivalent was 'We cannot bet the Mansion.' We cannot make a bet financially that, if it doesn't work, I have to call my father and tell him I've found a lovely one bedroom in Westwood."

Christie Hefner was replaced by a self-described change agent named Scott Flanders. "This needed a new set of eyes," he says. He spent the first three months of his tenure reviewing the company's books before he made a startling announcement to Hefner and the board: Playboy wasn't going to make money as a media company anymore. There were too many other ways for American men to find what Playboy alone had once offered them. But the company could still make money as a brand. Playboy's value was in the name and the white rabbit and the images it still evoked for 97 percent of people around the world. The magazine, which even now loses millions of dollars a year, might still exist as a kind of engine, as the narrative that sells the products, but it was in global licensing agreements—in T-shirts in the Czech Republic and a beer in Brazil, in bath products and bottled water—that it would find its profit. Flanders was surprised when Hefner and the board agreed.

Even more significantly, Playboy went private in 2011. Flanders swears that the move was Hefner's idea; Hefner says it was, too, but he can't remember the seeds of it. The hitch was that Hefner didn't have enough money to buy the company from its shareholders on his own. He needed a partner with deeper pockets, and he found one in a private-equity firm, Rizvi Traverse Management. A prolonged series of negotiations ended with Hefner owning only a minority stake in the company he'd founded—34 percent against Rizvi's 60—but with contractual control over the twin pillars of his existence, the magazine and the Mansion.

However necessary the move was, it was the sort of compromise that nobody could ever have imagined Hefner making. He suddenly had become an employee of his own company, earning $1 million a year for his editing and ambassadorship, and a tenant in his own home, paying an annual rent of $100. The new company either licensed or auctioned off its TV channels, satellite radio station, and digital outlets. Its venerable Chicago offices were closed, hundreds of employees were laid off—but none at the Mansion—and remaining staff were moved into new, spare concrete-and-glass offices in Beverly Hills. The dozen or so original LeRoy Neiman paintings were shipped across the country and hung on the walls, but little else of the original Playboy remains. There is only Hefner, and his magazine, and his Mansion. "I'm a very successful businessman, but I don't really give a shit about business," he says. "Those were the only things I ever cared about." The rest of Playboy is now just an idea, available for a fee.

Cooper Hefner, the spitting image of his father, has emerged as a possible successor; just the mention of his name causes Hugh Hefner to smile. For Cooper, Playboy is in the midst of a much-needed internal revolution that he would like to help see through. "This is my family's legacy," he says, even sounding like his dad. "I should be the toughest critic. I was sitting upstairs looking at the Marilyn Monroe issue and the Bree Olson issue [from August 2011], and I was thinking, How did we come to this? What we were is not what we are today." Cooper—still in college, a senior at Chapman University, south of Los Angeles—has pored over the scrapbooks, and he has sometimes stopped in amazement, staring at a photo of his father standing shoulder to shoulder with Bill Clinton or John Lennon or Malcolm X. He knows that Playboy was once more than a magazine, the company more than a white rabbit. It was an electrical current. It was brave, and he wants it to be that way again. "I don't want us to be afraid anymore," he says.

To run Playboy's day-to-day editorial operations, Hugh Hefner has hired a thirty-eight-year-old insane person named Jimmy Jellinek, a ball of hair and kinetic energy. Today he's wearing a Brian Jonestown Massacre T-shirt. (When he took his first exploratory phone call from Playboy, he was literally in the middle of a keg stand in Lake Tahoe.) Jellinek had been an accomplice in the magazine's attempted murder when he edited in the early 2000s the then-ascendant lad magazines FHM, Stuff, and Maxim. Now he's aiming for a more lasting, resonant experience. As with his scrapbooks, Hefner has a system within which Jellinek must operate. Hefner still chooses the centerfolds, cartoons, and party jokes. He still reads and comments on many of the stories. The Playboy interview still has three photographs at the bottom of the first page. But within that frame, Jellinek has room to build a universe of his own. "We've created this little world where you can turn off the constant hum of the TMZ feed that's rotting your brain," Jellinek says. "Lean back. Read something with substance." Hefner always said that his magazine was like a Rorschach test, as much a mirror as a window. In it, Jellinek sees beauty and possibility. "The opportunity to play with words in an analog paper magazine—you have to treat that as a privilege," he says. "If you forget that, that's when you fall down the rabbit hole and you're writing on the Internet at home in your underpants. I'd rather put a gun in my mouth."

Like most men over thirty, Jellinek can remember his first Playboy nearly as clearly as his first kiss. How many moments of heart-thumping teenage discovery have there been in the last sixty years? "So many people do remember," Hefner says. "I have been told this, with elaborations, hundreds of times. That gives you a clue how unique the whole experience was. I didn't just start a magazine. I started a magazine that changed everything."

It changed everything for Jimmy Jellinek, a nice Jewish kid from Highland Park, Illinois, future barefoot editor, and Brian Jonestown Massacre fan. He stole his first copy of Playboy from his friend Danny, who had bought it from their friend Matthew, who had slipped it out of his father's collection. It was the May 1987 issue, with Vanna White and the crack of her ass on the cover, which was something of a scandal, back when an ass crack could scandalize. "Danny had this nook under the stairs, like a boy fort," Jellinek says. "That's where we were ushered into manhood."

Now overwhelmed by nostalgia, he turns to his shining computer screen and calls up Playboy's new digital archive. He finds the issue, easily and immediately, this formerly precious, almost religious object. It's all right here again. He starts clicking through. There's fiction by Larry McMurtry. There are ads for Isuzus and cigarettes. Barbara Hershey and Phil Collins make appearances, and there's the Playboy interview, this one with Norodom Sihanouk, former and future king of Cambodia and a really hard man to masturbate to.

And now here she is, in all her glossy glory: Miss May, Kym Paige. She is the classic Playboy centerfold, another one of Hefner's girls next door—if next door were a barn and the girl sometimes sat on the fence with her blouse open and her skirt hiked up. Jellinek looks at Paige for the first time in more than a quarter century, at this object of his teenage imagination, and she hasn't changed a bit. Out there, she's forty-seven years old. But in here, in this glass-box office in Beverly Hills in 2013, Kym Paige is exactly what she was in 1987 and will be forever. For some people, there is no succession plan because they will never cease to exist.

It's Friday night, which means it's Movie Night. At the bottom of the driveway, an open-topped tour van has stopped, and its conductor is shouting something about "Heaven on Earth." His passengers take pictures and gasp each time another car pulls up: Who could be so lucky to have those gates open for them?

Some of the boys are here again, including Ray Anthony and Keith Hefner, but there are far more women than men tonight at the Playboy Mansion. An older woman with swollen lips gets up from her seat and announces: "I'm the only blond in here who hasn't fucked him," and nobody corrects her. There are several former Playmates and apparent conquests spanning generations lined up at the hot buffet, filling their plates with steaming shrimp, roasted chicken, exotic and unidentifiable vegetables. Joyce Nizzari — Miss December 1958 — is here, still smoking at seventy-two. One of The Wild Women of Wongo ("Prehistoric Beauties Live by the Code of the Jungle!"), Nizzari continues to work for Hefner as an executive assistant. Also present: Kara Monaco (Miss June 2005, and the Playmate of the Year 2006); Deanna Brooks (Miss May 1998); Shera Bechard (Miss November 2010); Ava Fabian (Miss August 1986); and Heather Rene Smith (Miss February 2007, and a featured player in episode eighteen of Playboy TV's "Hot Babes Doing Stuff Naked," in which the stuff she did naked was camp). There are two more hopeful young women, fresh-faced and gorgeous, who have come to Los Angeles to have their test photos taken. Crystal, in her Uggs and on the hunt for a piece of cake, eyes them with suspicion. They in turn look at the other women, at their possible future, the way the men do, with the same baffled combination of joy and disbelief.

One older, elegantly dressed woman sits quietly at a side table. Her name is Monika Henreid. She is the daughter of Paul Henreid, the late strapping Austrian actor who played, among dozens of roles in a long career, Victor Laszlo in Casablanca. Hefner believes that Casablanca is the greatest movie ever made—"the perfect film," he says—and for decades his birthday parties have been tributes to it. The men wear tuxedos with white jackets and the women wear glamorous period costumes, and they sit down together and watch Humphrey Bogart and Ingrid Bergman on that same white screen year after year. At one of those parties, maybe eight or nine years ago, someone decided to bring Monika Henreid as a gift for Hef-ner—not as a sexual sacrifice, but as a link, however tenuous, to Casablanca: Here is the daughter of Victor Laszlo, heroic antifascist. Hefner was delighted. And like so many others who have entered his orbit by some accident of fate, Monika Henreid has never really thought to leave it.

Hefner, for the moment, is upstairs again, being tended to by his concerned doctor. He still has not recovered from his tooth extractions and didn't sleep much again last night. Years ago he would go on three-day writing benders, fueled by Dexedrine and his pathological ambition. He is starting to look the way he did back then. His house should probably be empty, and he should probably be in bed. Instead, he is running around his bedroom, panicked, because he risks being late to start the night's movie, for which there is no vote: My Favorite Brunette, from 1947, starring Bob Hope.

Hefner's bedroom: a giant wood bed, ornately carved, maybe with mermaids, definitely with tits, and that could be a pineapple. Black satin sheets and lots of pillows and one of those fuzzy fleece blankets that's usually found for sale at country fairs, this one featuring a life-sized Marilyn Monroe, folded so that it appears she's stretched out at the foot of the bed. A large mirror on the ceiling above said bed. A bust of Frankenstein and one of Dracula. A ray gun in a glass box. A really big security guard, just hanging out. Books on Frank Sinatra and Jimmy Hoffa. Piles of magazines. Two movie screens, side by side, and several blown-out-looking tube TVs, built into the wood ceiling. A chandelier, upon which hang dozens of pairs of lace underwear. A curved couch, covered in stuffed animals. Betty Boop. Mickey Mouse. A statue of the Rocketeer. A beautiful spiral staircase leading up to his office, where Kimberley Conrad waits for her rescue from the rising stacks. A clipping of his Playboy Philosophy from May 1966. His NAACP Image Award from 1976. A black-and-white photograph of Hefner as a toddler, staring thoughtfully at a wood toy. Directly in front of it, a small sculpture of a man railing a woman from behind.

Now he dashes through his walk-in closet and into the bathroom. "So many pajamas!" he shouts, and sure enough he has many pajamas. They are ironed and on hangers, sixty or seventy pairs, sorted by fabric and color, from the black silks on the left to the pale-blue flannels on the right. There are also a dozen pairs of the same black slippers on shelves nearby, and his trademark captain's hat, and five or six copies of the same silk robe, crimson and square in the shoulders. It looks more like a costume department than a closet. It looks make-believe. This place is ridiculous. This place is perfection. "You can't live somebody else's life," he says, but he did. He never should have been able to live this life, and he knows this to be true. "As big as my dreams were"—in those darkened movie houses, in places other than his mother's arms, these dreams that he doesn't have anymore—"they certainly didn't begin to match what came to pass. Who could have imagined a life like this before the fact?"

And he's right. Before his father got married again, Cooper had asked him if he was worried what people thought, and he said: "Fuck them." Fuck them. Out there, it's easy to make fun of him, because he's old, and old people are easy prey. Not at the Playboy Mansion. In here, nobody commits the sin of forgetting that old people were once young. Nobody forgets what he's done. In here, nobody forgets.

Now he races downstairs, watching the clock, nearly frantic. Late, he's going to be late. He doesn't even take the time to change out of his sleeping pajamas and into a pair of the silks. He is never seen in them, not in public like this, not in his version of public anyway, and like Mary O'Connor's too-late wishes, the sight of his sleeping pajamas is enough to spark another round of sad whispers at the Mansion. They represent yet another tiny bellwether, another reckoning, and everybody noiselessly wonders how many more of these nights they have left. It's impossible to know—Grace Hefner lived to be 101—but there will be many less than there have been. All these little cracks. All these little changes. Sometimes it feels as though the end is coming and that's the only absolute left in this house of former absolutes. And what happens then?

Playboy will survive, at least as a company, as a business proposition, as a brand owned and managed by private-equity firm Rizvi Traverse Management. The white rabbit will still be on T-shirts in the Czech Republic and beer bottles in Brazil. The magazine will probably continue to exist in some shape or form, profitably perhaps only in countries like Mongolia, like Thailand, where it still means the things that it doesn't mean here anymore. There are still places in the world where Playboy represents change, not changelessness. Cooper Hefner might succeed in becoming the company's new face, which will look so much like the old face that it will take a moment to remember that the party, this particular party, will be over. It's not just this universe that will collapse when it loses its center. It's not only these bizarre, beautiful, damaged, openhearted people who will be left homeless, who will be cast adrift absent the anchors of Manly Night and Mexican Train. All of us will lose something. Hugh Hefner is no longer ahead of his time; time has caught up with him. And you can feel, late at night, when the Mansion is quiet, that this place is already a museum, and it isn't hard to imagine those tourists in the van at the bottom of the driveway lining up for their tickets to Heaven on Earth and being allowed through that gate, and they will look at these rooms, at the bed with its black satin sheets, at all that dusty underwear hanging from the chandelier, and they will smile and shake their heads in wonder. But Playboy, at its best, wasn't just an artifact of its time. It helped make us who we are. Yes, Hefner's magazine was a Rorschach test. It was also a stick in your eye. "It had lightning bolts coming out of it," Jimmy Jellinek says. For sixty years, Playboy has been on the right side of history—on sex, birth control, civil rights, AIDS, gay marriage, war, social tolerance, personal liberty—while also serving as a vehicle for that history. But it wasn't Playboy, really. It wasn't the brand or the rabbit. It was him. It is him. And without him, it will be no more.

That's not a very nice thing to think about. Why even think about it? It's better to stay here, fixed in time and space, and to escape into another movie, into another Movie Night in a lifetime of Movie Nights. In the interest of time, Hefner dispenses with his usual introductory speech, which he normally reads from notes written by his friend Dick Bann. This further departure from routine is also regarded solemnly, but soon the room rallies, and Hefner receives his customary round of applause all the same. Then the lights go out. The movie starts. Here is our host, only a little behind schedule, with his wife at his side, and his brother behind him, and his friends all around him. Hefner pulls up his blanket closer to his chin, making sure he's sharing it with Crystal, making sure she's comfortable and enjoying her piece of cake. Then he sinks back into his favorite spot on the couch, and all things are possible. The place feels warm, and it smells like popcorn.

Published in the April 2013 issue under the headline "Gentlemen, Gentlemen, Be of Good Cheer, for They Are Out There, and We Are in Here."