Scarlet (or not) Sophronitis: The Return of the Red Hots

SO-phro-NOT-Cattleyas

by Jay Vannini

A very fine late summer display of Sophronitis mantiqueirae ‘Ron’s Red’ AM/AOS in the author’s California collection. Did I say, “red hots”? This cool-growing miniature orchid is visually stunning despite its small flower size. This species is best grown cool and will languish under warm tropical conditions. Commonly confused with the diminutive S. pygmaea, which has tiny flowers and globular pseudobulbs. Author’s image.

Red is a color particularly prized by gardeners in general and orchid growers in particular. Those orchid genera that contain relatively high numbers of red-flowered species, such as Disa, Masdevallia, Epidendrum and Sophronitis, are extremely popular with collectors and breeders.

A nice 1990s vintage colchicine-treated Sophronitis coccinea in my collection in Guatemala. Even run-of-the-mill modern treated plants show a great improvement in flower quality when compared to 20 years ago.

Sophronitis sensu amplo (Laelinae) is a small (eight more or less accepted species), easily recognized orchid genus with mostly localized species that are endemic to the uplands of southeastern Brazil although one (S. cernua) ranges more widely into the lowlands of eastern Bolivia, Paraguay and northeastern Argentina. They are characterized by their compact growth habits with yellow, orange, red, pink or magenta-colored flowers emerging together with new leaves, globular or spindle-shaped pseudobulbs and very succulent foliage, often with a dark mid-stripe on the leaves. Most species originate from low to upper elevation cloud forests between ~2,000-7,500’/~600-2,300 m, where they grow as both lithophytes and epiphytes in moisture-drenched environments. The one outlier, again S. cernua, is primarily a lowland species that ranges from coastal mangrove forests to about 2,000’/600 m elevation in very warm, often seasonally dry ecosystems where they can form immense colonies on older trees under optimal conditions.

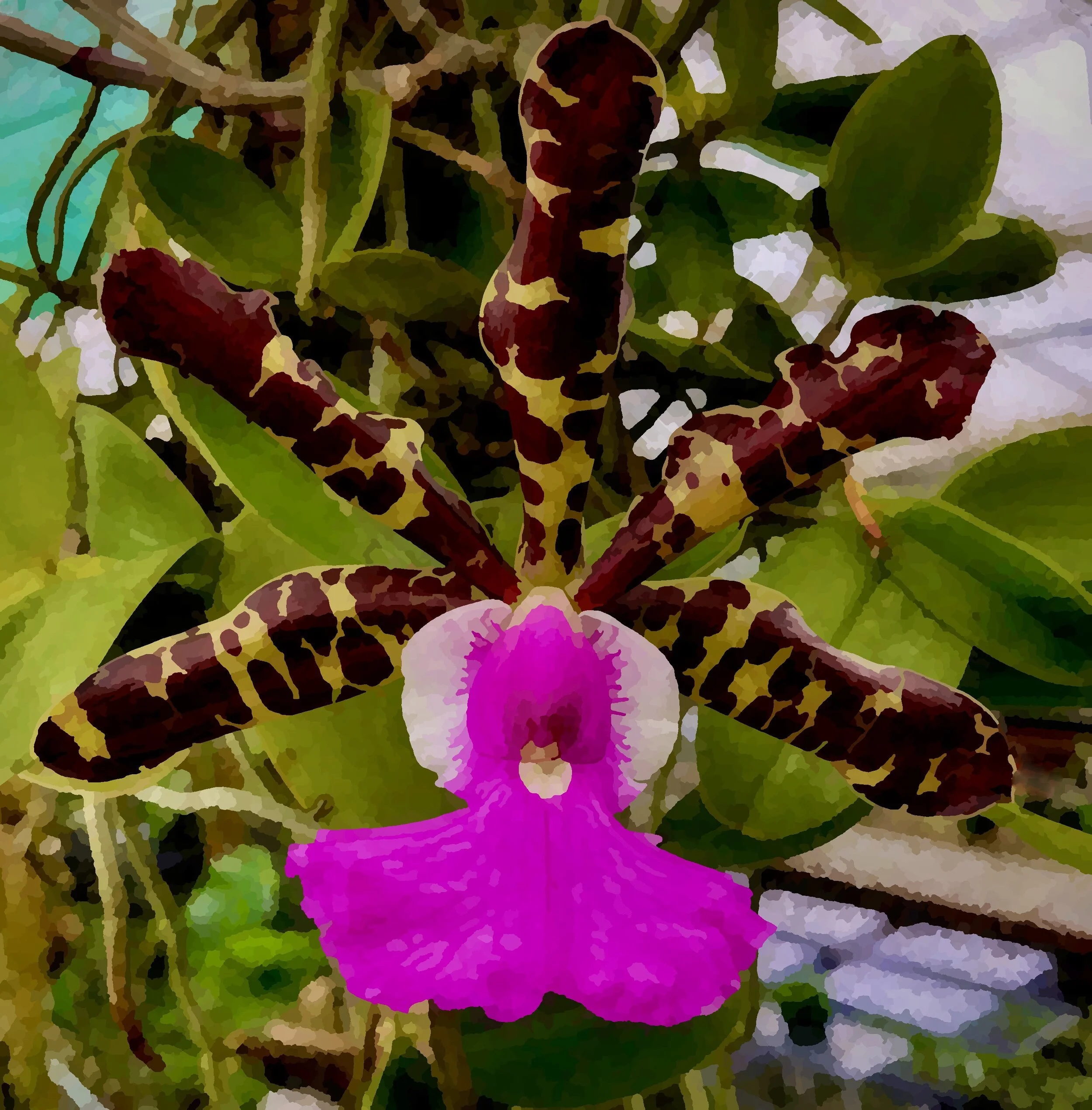

Another late summer flowering species in California, Sophronitis bicolor.

Long popular with orchid breeders because they impart red colors and compact growth habits to their offspring (including many of the so-called Mini-Catts), Sophronitis are the “Sophro-“ or Sophra-prefix and -onitis-suffix to some laeline nothogenera (i.e. generic names created to denote hybrid origin). Most species have flower colors that are some shade of red, although S. wittigiana is pink or pale magenta. Some of the better-known red-flowered species also have orange and yellow-flowered forms in cultivation, variously labeled as forma aurea, flava, xanthina and xanthoglossa as well as under archaic varietal names such a var. lobbii. As more line bred and imported plants enter cultivation outside of Brazil, small numbers of splash-color type flowers have also appeared in the trade. Crosses of improved yellow and red flowered forms of S. coccinea have appeared on the market of late, mostly from Japan, and some clones I have seen appear to blend these primary colors well.

The classic Sophrocattleya Batemaniana (Sophronitis coccinea x Cattleya intermedia) is a very early laeline hybrid made in 1881 at the Veitch Nurseries in England. This cross, first flowered in 1886, was used in many hundreds of subsequent hybrids. The Veitch Nurseries followed Sc. Batemaniana with a variety of other primary hybrids involving S. coccinea, such as Sc. Calypso (x C. loddigesii), Sc. Eximia (x Guarianthe bowringiana), Sc. Queen Empress (x C. mossiae) and Sc. Saxa (x C. trianae) (Veitch 1906).

In Volume III of “The Cattleyas and their Relatives” (1993), Carl Withner includes a quite good overview of the genus with sound cultural recommendations and a few very interesting photos; unfortunately with a couple questionable IDs and generally mediocre color renderings. At that time, the yellow-flowered forms of Sophronitis coccinea and S. cernua were exceedingly rare in cultivation outside of Brazil, so only one image of this type of variant was provided, incorrectly labelled “Var. flava”. Withner provided a detailed list of the horticultural varietal names published up to that time, most of which are now considered merely color forms, as well as subspecific names for plants that had been described as such.

Sophronitis coccinea f. flava ‘Yellow Bird’ x sib in the author’s collection. ‘Yellow Bird’ was also selfed by Japanese breeders and put into plant tissue culture. The offspring I have seen are generally good, if somewhat small. Author’s image.

Given their great beauty, diversity and native status, it is not surprising that they are extremely popular with Brazilian orchid collectors where they are known as Orquídeas Vermelhas. Famed British botanical illustrator Margaret Mee painted a number of Sophronitis species from life during her time there working for the Instituto de Botânica in São Paolo in the 1960s. In “Orchids of Brazil” (1993) Australian orchid collectors McQueen and McQueen covered a selection of species and varieties known in country at the time. Hopefully, more of the unique color forms and distinctive ecotypes available to contemporary Brazilian collectors will be imported to the U.S. in the near future. They are also favored by Japanese orchid breeders, which is the origin of many (most?) of the improved plants in U.S. cultivation. A casual perusal of images online shows many outstanding clones and distinctive ecotypes grown to perfection by growers in both countries.

A nice group of different color and flower forms of cork-mounted Sophronitis coccinea blooming in the author’s collection in California during mid-March 2023. More-or-less clockwise from top center: S. coccinea f. xanthoglossa ‘Ros’ (86 mm spread across petals for scale), an unnamed S. coccinea f. xanthoglossa outcross, S. coccinea ‘Fake Pygmy’, S. coccinea f. flava ‘Yellow Bird’ x sib, S. coccinea f. flava ‘Laranja’ outcross, and S. coccinea ‘Testarossa’ (large-flowered, colchicine-treated clone - single flower on a recent division shown upper left). Image: ©Ron Parsons 2023.

A large flowered, very fine example of treated Sophronitis coccinea bred in Japan. Grower: Tom Perlite, Golden Gate Orchids.

Because of their rather small flowers in nature, since the 1980s they are often chemically treated at seed or seedling stage to try and induce polyploidy and its often-resultant added flower size and plant vigor. “Tetraploids” or “4n” is a bit of a misnomer since many plants as well as subsequent generations haven’t been tested for ploidy, so “treated” or “probable polyploid” is more accurate.

Among some very rare color forms seen in the rose or pink-flowered species, Sophronitis brevipedunculata and S. wittigiana do produce very pale, caerulea and albescens-types. The only flower of this shade that I have seen in life was of the former species and was–sadly and despite having nice shape–a muddy shade of pale whitish-salmon. Withner (1993) shows an image of the very pale colored ‘Ericka’, awarded an AM by the AOS in 1967. Pure albino forms of S. wittigiana do appear on the market from time to time, mostly in the EU and Brazil; the ones I have seen for sale recently in northern Europe were extremely expensive, even for such a rare orchid form. Fowlie (1968) reported a pale ecotype of S. mantiqueirae from the Pico do Cristal in Minas Gerais state as var. veronica with yellowish to salmon colored flowers.

Sophronitis coccinea treated x S. coccinea f. flava. Grower: Tom Perlite, Golden Gate Orchids.

A couple species other than Sophronitis bicolor produce individuals with scarlet petals and sepals with bright yellow lips, commonly called var. or f. xanthocheila. While often an extra attractive feature in the other taxa, this is probably best considered a striking color form than a true variety.

I currently grow all of the recognized species, including one that matches the description of Sophronitis pygmaea*. I also have several of the more noteworthy color variants in my collection, but am still looking for good examples of the splash-petals, salmons and albas.

An awarded, tested tetraploid Japanese Sophronitis coccinea has the dubious distinction of being, until quite recently, the most expensive plant that I have ever purchased. The small division was maladapted from the git-go but did flower twice before beginning a multi-year decline that I could not arrest despite best efforts. Ironically, this is the only Sophronitis plant that ever croaked on me and, to add insult to injury, I have also seen several better quality plants for less than half the price in the years following its untimely demise.

Other than larger flower size, one of the key tells indicating colchicine-treated Sophronitis coccinea and S. wittigiana as well as their offspring is the shape of the lip. Most of these plants have very round lips, as opposed to acute/acuminate or narrow spade-shaped lips seen on flowers of plants of wild origin and their untreated offspring

Shown above, two untreated Sophronitis coccinea in California with typically small (~2”/5 cm) flowers. Left, the author’s S. coccinea f. flava, said to have been imported from Brazil and of wild origin; and right, an anonymous grower’s “Cor de gema”, S. coccinea f. rossiteriana.

A very free-flowering Sophronitis cernua flowering in the author’s home. While flowers are of average quality, this clone reliably produces six+ flowers per growth.

Most species other than Sophronitis cernua produce only one flower per growth, although I have clones of both S. coccinea and S. wittigiana that produce twin flowers per pseudobulb on a fairly reliable basis. In contrast, my best mature examples of S. cernua will invariably produce six to eight flowers per growth.

Although many very fine Sophronitis specimens have been grown in pots over the past hundred plus years, I follow many of my friends and acquaintances lead in growing them mounted. While somewhat more attention to care, especially watering and fertilization, is required I find the plants are overall more floriferous and healthier when grown on cork mounts or in durable wooden baskets. I have also grown them successfully on tree fern plaques in Guatemala, which is a very popular option with some Brazilian collectors. Another alternative for those with space for permanent display and very large clones they can divide is a large, suspended cork tube or standing hardwood log. Both these options are also employed by some growers in Brazil and videos and images posted on the internet by them show that they can produce very fine table or bench displays when in flower.

The “correct” generic name for orchids discussed here as Sophronitis remains a subject of some debate among orchid specialists. The prevailing widespread use of the generic name Sophronitis is frowned upon by the orchid taxonomy wallahs and Kew’s The Plant List. The rationale for lumping it into Cattleya is provided in “New Combinations in the Genus Cattleya” (van den Berg 2008) and summarized in “The New Cattleyas” (Higgins and van den Berg 2010) as follows:

“Because Cattleya, as previously circumscribed, is paraphyletic to Sophronitis s.l., it would require the creation of many new genera for the various subgroups of Cattleya thus requiring new nothogenera for hybrids. A more practical (and simpler) solution is to lump all Sophronitis s.l. species with Cattleya and classify these groupings at the infrageneric level (subgenus, etc.). In this way, future infrageneric changes would not require further binomial changes, providing also nomenclatural stability for artificial hybrids of species in this alliance. Some species of the former Brazilian Laelia and Sophronitis had originally been placed in Cattleya and van den Berg (2008) has renamed the other species.” (emphasis mine).

Flower detail on a very full-flowered form of Sophronitis brevipedunculata in the author’s collection.

The American Orchid Society (AOS) had already weighed in on this a year earlier:

“There are effectively two solutions; creation of new genera for the various subgroups of Cattleya or lump all Sophronitis species with Cattleya and deal with these groupings as subgenera or sections of a greatly expanded Cattleya. This latter solution provides better nomenclatural stability for artificial hybrids of species in this alliance since changes would not result in transfers to new genera….

…At the World Orchid Conference in January 2008, International Orchid Committee met to discuss the situation and, with input from the RHS Advisory Panel on Orchid Hybrid Registration (APOHR), the authors of the additional studies, the Orchid Hybrid Registrar (the Registrar), the AOS and editors of Genera Orchidacearum agreed that sinking Sophronitis into Cattleya would be a better approach over the long term.” (emphasis mine).

In other words, “What a pain in the ass it would be for the registrars at the RHS and AOS to leave Sophronitis as a separate genus.”

As an alternative to this route, a very knowledgeable and practical-minded acquaintance familiar with this debate (T. Kennedy, pers. comm.) recently suggested that a better option is to “freeze” nothogeneric names under seniority rules governing standard botanical nomenclature and resist the temptation to change generic names of orchids solely to suit horticultural, pragmatic or taxonomic whims.

Despite the fact that more than a decade has passed since the taxonomic opinion was published by Cássio van den Berg most nurseries and private collectors in the U.S., as well as many in the EU, are reluctant to observe the decision to move Sophronitis into synonymy with Cattleya. Indeed, more than 10 years after the fact it is rather rare to see them offered for sale as Cattleya species outside of Brazil. This stands in contrast to widespread acceptance of the name changes of other “natural genera” of Laeliinae such as the Mesoamerican Guarianthe and Rhyncholaelia.

Noteworthy publication dates for the genus are as follows:

Sophronitis cernua - Lindley 1828

Cattleya coccinea - Lindley 1836

Sophronitis - Berg and Chase 2000

Hadrolaelia - Chiron & V.P. Castro 2002

Cattleya - van den Berg 2005 and 2008

At this time the generally accepted species are:

Sophronitis acuensis Fowl. 1975. One of the smaller species, in both plant and flower size. These are upper elevation plants from the Brazilian state of Rio de Janeiro. Some color variation is evident among flowers with individual forms often showing faint splash-petals with pink or magenta overlaying orange or red ground colors. Late winter/early spring blooming in California.

Shown above, two color forms of Sophronitis acuensis. Left, a very free-flowering clone grown by Cynthia Hill. Right, a single flower on a young plant of the author’s with some magenta showing on the edges of the petals. Both plants originally from Florália Orquídeas in Rio de Janiero, Brazil.

A pair of Sophronitis acuensis ‘CHill’ flowers in the author’s collection; flower on the right just starting to fade. Author’s image.

Sophronitis bicolor Miranda 1991. A robust, very showy-flowered species from Espírito Santo state and formerly considered a variety of S. coccinea. Plants have an open habit, elongated pseudobulbs and very showy single bright orange or red flowers with yellow lips held well free of the foliage on an elongated peduncle. While blooms on almost all Sophronitis species can take a couple weeks to open and fully expand to final size and form, S. bicolor flowers seem to be exceptionally deliberate in their development and can take up to three weeks to expand fully. Late summer and early fall blooming in California.

Two large-flowered clones of Sophronitis bicolor in flower in the author’s collection, late September in California. Left ‘Orange Gem’ and right, ‘Highland’.

Sophronitis brevipedunculata f. aurea. Bow-tie petals that are constricted basally are rather common in this species. Image: R. Parsons.

Sophronitis brevipedunculata (Cogn.) Fowlie 1972. A very beautifully flowered species formerly considered a variety of S. wittigiana from seasonally dry upland mist forests of Minas Gerais, Rio de Janeiro and Espírito Santo states. Its pseudobulbs are clustered and nearly globular, much like those on S. wittigiana and some S. cernua. Flowers are held close to the plant and can be very handsome on the larger-flowered forms. This species is a mid fall to early winter bloomer in California. Flower buds are unusual in the genus in that they are light green until almost opening. If grown potted, this species should be allowed to dry out between waterings, particularly after flowering.

A very attractive clone of Sophronitis brevipedunculata flowering in the author’s collection. Flower shape and color show its affinities to S. wittigiana, although most examples I have seen tend to be markedly redder than in this individual.

An exceptionally fine coral-colored flower form of Sophronitis brevipedunculata, ex-Japan. Due to its color and shape, the similarity of the flowers of this clone to those of S. wittigiana is particularly evident. Grower: Tom Perlite, Golden Gate Orchids. Author’s image.

A more typically-colored flower of Sophronitis brevipedunculata. This selection, ‘Little Red’, has nice flower form with noticeably round and flat segments but is…ummm…just a tad little. Span across petals usually tops out at just over 2”/5 cm. Author’s plant and image.

Nice form on a young example of the orange flower phase of Sophronitis cernua. Authors’ plant and image.

Sophronitis cernua (including S. alagoensis and S. pterocarpa) Lindl. 1828. A very widely distributed species across much of eastern Brazil, northern Paraguay, Uruguay and northern Argentina. Easily grown and there are many improved plants, included colchicine-treated stock, in collections. Mature plants hold from three to 10 flowers per inflorescence, with young plants often throwing singles or twins. Fall and winter blooming in California. As is also the case in S. coccinea, an old, very large, well-flowered colony is a spectacular sight. Most plants have small, cupped, pale orange flowers with narrow segments, but there are increasing numbers of improved plants with better flower form and color on the market and in collections. Color variations include both pale pinkish orange and a variety of bright yellows tones. A California Mini-Catt breeder, Peter Lin, has used this small species frequently in complex hybrids to create a series of tiny, showy-flowered laeline hybrids that he calls Micro Mini-Catts.

Sophronitis cernua f. aurea ‘Yellow’ x ‘Limone’, author’s plant and image.

Sophronitis cernua ‘Spring Hill’ x self in the author’s collection. Selfing of a very pale orange form that generated much darker flower color in F1.

A very fine treated form of Sophronitis coccinea growing in NZ sphagnum moss in a clay pot. Growers: Alek Koomanoff and Golden Gate Orchids.

Sophronitis coccinea (Lindl.) Rchb. F. 1868. The poster child for the genus and a large, select form in full bloom is one of the world’s most beautiful orchids. From intermediate to middle elevations in mossy forests of the states of Rio de Janeiro, São Paolo and Minas Gerais. They flower mostly from late fall to mid-winter in California and the single or twinned blooms can last for several weeks in good condition if kept cool and dry. Flower colors range from pale yellow through deep orange and scarlet, with varying amounts of yellow on the labellum. While some of the muddy orange colored forms known as var. rossiteriana can be disappointing in person, f. Borboleta with its orange and yellow-splashed floral segments are very attractive, as are those rare individuals with pure mandarin orange-colored flowers. Unfortunately for foreign growers, this color form is not commonly available outside of Brazil at this time. While there are rumors of flowers on treated S. coccinea exceeding 4”/10 cm in diameter, the largest flowers I have grown in my collection were just over 3.4”/8.5 cm in diameter. I have seen a couple flowers in person as well as images with scale references that were almost 3.6”/9 cm across. “Wild” type untreated examples of the species are considered excellent if they have good form and color with anything much beyond a 2”/5 cm spread.

Sophronitis coccinea f. flava x S. coccinea ‘Laranja’. Author’s plant and photograph.

A beautiful example of an untreated, wild-type scarlet Sophronitis coccinea, the ‘Marsh Hollow’ clone unfolding in early Autumn. Grower: Cynthia Hill. Author’s image.

Sophronitis coccinea f. xanthoglossa. Author’s plant and image.

Sophronitis coccinea f. flava ‘P’ in the author’s collection. This is a very large yellow-flowered clone of the species with intense color, nice form and 3”/7.5 cm wide blooms. The product of careful line breeding in Japan, apparently untreated.

Sophronitis mantiqueirae (Fowlie) Fowlie 1968. Another fairly wide-ranging, small flowered and color variable species from southeastern Brazil, occurring mostly at intermediate to upper elevation cloud forests in the states of Rio de Janeiro and Minas Gerais. May flower twice annually. As mentioned earlier, some ecotypes have very pale colors in nature (var. veronica), while others have brilliant red flowers with yellow lips (f. xanthocheila).

Rodrigues et al. (2014) examined the relationships between naturally occurring, disjunct populations on plants previously identified as S. mantiqueirae and S. coccinea in the Serra da Mantiquiera, Serra do Espinhaço and Serra do Mar in Brazil’s southeast coastal Atlantic. Based on DNA analysis, they concluded that plants in these regions merit reexamination as regards their taxonomic status, and likely include at least one new species and (perhaps) natural hybrids with S. brevipedunculata.

A young Sophronitis mantiqueirae flowering in the summer in California. This clone was one of those sold as S. pygmaea.

Sophronitis pygmaea (Pabst) Withner 1993. Carved out of S. coccinea and elevated to full species status by Withner. In his description he mistakenly refers to it as the smallest member of the genus, which is actually the miniature, lowland ecotype of S. cernua from Alagoas state formerly identified as S. alagoensis. It is, however, the smallest of the “scarlet” Sophronitis species, with flower span mostly ~0.75”/2 cm in diameter. I am not familiar with this species in life*, but it is almost universally misunderstood and confused with the much larger flowered S. mantiqueirae. Many plants sold in the U.S. under this name in recent years key to S. mantiqueirae when in bloom.

The flower displayed in the image in Withner (1993) taken by Robert Kaustky and labeled Sophronitis pygmaea ‘Mignon’ is not shown to scale and appears to be a mediocre-quality S. coccinea. I have not been able to locate an image of plants matching the description of S. pygmaea online; all plants shown appear to be either small S. coccinea, S. mantiqueirae or hybrids.

*November 2022 Edit: Over the past two years I have purchased several Sophronitis cf. coccinea that were imported from a respected Brazilian nursery by U.S. intermediaries and sold as genuine S. pygmaea. Until recently, all of the plants that have flowered resolved as small-flowered forms of S. mantiquierae. This spring I was given a division of a plant labeled S. pygmaea that is also a direct import. The plant has now flowered and, while the pseudobulbs are 3 mm wide and elongated, the leaf morphology amd 0.75”/20 mm wide red flower does match the diagnosis especially with regard to “pointed segments”. One interesting aspect of the flower is that, unlike those of other Sophronitis species, it does not expand much after opening.

Sophronitis wittigiana Barb. Rodr. 1878. Another of the standouts in a genus replete with beautifully flowered species, S. wittigiana (formerly known as S. rosea in the trade), have large, full, very flat flowers, in shades of vivid pink and often overlaid with darker contrast veins and giving them a pin-striped look reminiscent of some modern hybrid Phalaenopsis flowers (see below). From low intermediate to upper elevations in Minas Gerais and Espírito Santo states, plants should be grown under intermediate conditions for best flower color and life. My experience is that plants must be kept on the dry side during winter flowering or blooms will blast in short order. Colchicine-treated plants and their offspring now dominate selections offered by U.S. and Japanese nurseries, but wild origin plants can also often be of high quality and the better forms are definitely worth having in one’s collection.

Two exceptional Sophronitis wittigiana clones grown in California. Left, plant grown by the author ex-Japan and right, a clone grown by Cynthia Hill (‘Pink Opal’ AM/AOS x ‘Diamond Orchids’) and bred by Peter Lin, also from Japanese lines. Images: R. Parsons.

Cultivation:

I have been growing Sophronitis species for over 20 years, starting in Guatemala with early treated S. coccinea clones from Orchids Limited and some of the other species from Mountain Orchids and New World Orchids. Accessions beginning in 2011 in California have mostly been from Golden Gate Orchids, two Japanese nurseries and gifts from various friends in the San Francisco Bay Area.

A nicely-flowered Sophronitis coccinea of Japanese origin and from a treated flask growing in the author’s California collection. A sibling of this clone often produces twin flowers. Specimen-sized S. coccinea can remain in flower for almost two months as new growths continue to mature while older flowers fade. Note several near mature flower buds emerging from new leaves as they unfold.

Sophronitis species require medium to fairly bright light, cool nights, excellent ventilation and plenty of atmospheric moisture to thrive. Pure water is, unsurprisingly, a big plus. Exceptions are S. cernua and some ecotypes of S. wittigiana originating from the lower part of its elevational range. Species such as S. brevipedunculata, S. bicolor and S. coccinea do well grown intermediate to cool, and S. mantiqueirae and S. acuensis only thrive under very cool conditions. After having grown them for years in pots in a variety of media and mounted on treefern slabs and cork bark, starting in 2014 I have opted to grow almost all of my plants on cork bark. One exception is the large S. coccinea probable 4n shown growing horizontally on an 8”/20 cm hardwood slat mount. I have found these types of wooden mounts to be excellent for mounting orchids that tend to ramble horizontally at specimen size, particularly some of the larger laelines and Malesian bulbophyllums.

A superb flower on a wild form of Sophronitis wittigiana grown by well-known orchid specialist and author Mary Gerritsen in California. Image: R. Parsons.

Light intensity, nighttime temperatures and RH seem to have a greater impact on the intensity of color in the red flowered forms of Sophronitis more than any other orchid that I have grown except for Dendrobium cuthbertsonii. Beyond attention to these details to try and provide optimum conditions for the plants, many S. coccinea and S. wittigiana clones – even large ones – definitely exhibit on and off year flowering as well, where both flower size and number will usually vary significantly.

A trio of Sophronitis coccinea f. flava flowers on a mounted plant during mid-winter in the author’s collection in California.

It is worth noting to novices that Sophronitis, like some other delicate laelines, seem prone to drop flowers if moved to a different environment prior to the blooms fully expanding.

Several growers I know have succeeded with small Sophronitis coccinea grown in well ventilated terraria, and Withner describes an exceptional example flowered in a clear plastic hat box on a north facing windowsill in New York. I am confident that all of the species will thrive in modern Wardian cases equipped with advanced lighting, ventilation and misting systems using pure water.

I have been extremely fortunate in having grown these plants under near ideal conditions in both Guatemala and coastal central California so don’t consider them difficult to succeed with. Their easy culture under glass in fairly benign climates belies the difficulty that growers in fully lowland tropical settings may experience with cultivating taxa from upper elevation cloud forests. The most challenging plants in the genus for me have been the yellow-flowered forms of Sophronitis cernua, both from PTC and seed-grown. Some of these very touchy f. aurea/flava seem to require uniformly warm conditions and are maddeningly prone to “two steps forward, one step back”-type vegetative growth until they have some size on them. This requires a lot of patience and a bit of trial and error to find the right spot for individual clones. My somewhat limited experience suggests that they also greatly resent transplant, so get them on a permanent mount as early as possible. My fingers are crossed that I will finally flower a good one very soon.

A special thanks to Tom Perlite of Golden Gate Orchids, Ron Parsons and Cindy Hill for sharing rare plant material, their very valuable insights into growing these fabulous miniature orchids, and permission to use photographs and plants in their collections as models.

Two very good treated clones of Sophronitis wittigiana flowering in the author’s collection, December 2019. Most of these flowers will continue to expand for at least another 10 days.

Sophrolaeliocattleya Dream Catcher, a complex mini-catt hybrid of Slc. Beaufort (Sophronitis coccinea x Cattleya luteola) x C. Bright Angel (C. Precious Stones x S. coccinea). The double dose of S. coccinea in this very attractive miniature hybrid is clearly evident in flower shape and color. Grower: Tom Perlite, Golden Gate Orchids. Author’s photograph.