Cornea

March 2010

by Michelle Dalton

EyeWorld Contributing Editor

In order to prevent long-term ocular damage, treatment in the earliest phases of the acute disease is crucial

Stevens-Johnson syndrome is a potentially fatal disease, primarily affecting the skin and mucous membranes, and may have significant involvement of the oral, nasal, ocular, genital and lower respiratory tract. Typically, SJS is defined as detachment of less than 10% of the body surface area, with a variant of the disease, toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN), defined as a detachment of more than 30% of the body surface area. Mortality rates range from about 1–5% in SJS to almost 30% in TEN. With immediate efforts aimed at saving a person’s life, often the secondary afflictions, including those involving the eye, are not immediately addressed, and that can lead to severe long-term problems for the patient.

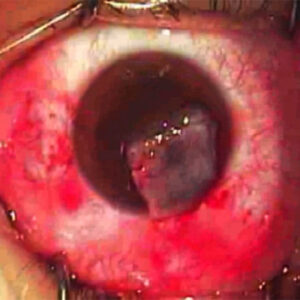

Source: Darren Gregory, M.D.

From an ophthalmic perspective, “this is one of the most difficult diseases to manage,” said Mark Mannis, M.D., professor and chair, Department of Ophthalmology & Vision Science, University of California Davis Eye Center, Sacramento, Calif. “As a result of the acute phase, critical components of the ocular surface have been severely damaged. A standard corneal transplant simply won’t work, because the patient’s surface won’t support a clear graft.”

The disease, an acute reaction to an inciting agent—often a medication—has been associated with almost every medication currently available, said Kimberly C. Sippel, M.D., assistant attending ophthalmologist, New York-Presbyterian Hospital, New York, and assistant professor of ophthalmology, Weill-Cornell Medical College, New York. Physicians have to restore the patient’s fluid electrolyte balance, keep the patient warm, and free of infectious agents as sloughing of the dermal layer puts them at high risk for death from fluid loss, electrolyte imbalance or infections, said Esen K. Akpek, M.D., associate professor of ophthalmology, and director, Ocular Surface Diseases and Dry Eye Clinic, Wilmer Eye Institute, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

“Older patients are most likely to die from the disease; the younger and healthier a patient is at presentation, the more likely they’ll have a long life ahead of them, but also more likely they’ll go blind if not treated during the acute stage,” she said. Although SJS can affect any age group, children are often afflicted, Dr. Sippel said. Medications associated with SJS include penicillins, sulfa antibiotics, anticonvulsants, and cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors. “If pediatric patients can survive the acute phase, they are often normal kids again in every way except in regard to the eyes,” Dr. Sippel said. “For those who do survive, the acute reaction has such an effect on the eye that it often doesn’t bounce back.” In the long term, these patients have severe ocular pain, and are extremely photophobic, she said. “Everyone is so focused on saving the patient that no one is really thinking about the eye initially,” Dr. Sippel said.

Indeed, the disease “can be devastating in its severe stage,” Dr. Mannis said. “Internists, dermatologists, and ophthalmologists all need to manage the patient, and need to mitigate the acute inflammatory stage.”

Studies have shown about 18%-30% of those with the acute phase have ocular involvement, “but over 90% will have scarring, long-term,” Dr. Akpek said. The acute stage “is where you really want to intervene and minimize the ocular sequalae that are so devastating,” Dr. Sippel said. The first two weeks of the illness is when treatment will be most effective, agreed Darren Gregory, M.D., associate professor, University of Colorado Hospital and Rocky Mountain Lions Eye Institute, Aurora, Colo.; and section chief, Ophthalmology, Denver VA Medical Center, Denver. “A month into the illness, and there’s not as good a prognosis for good visual function,” Dr. Gregory said. These patients “need to be at a center that has a burn unit during their acute phase, in order to manage the probable complications pertaining to various different organs and tissues which requires multi-specialty approach and multiple experts from various medical fields,” Dr. Akpek said.

Source: Darren Gregory, M.D.

Acute phase treatment options

As SJS/TEN progresses, “What basically happens is you get this sloughing of cells of mucosal surfaces, including the conjunctival surface,” Dr. Sippel said. “There is a good likelihood of symblepheron. The causative inflammation can affect the limbal stem cells, which affects the cornea. Once those limbal stem cells are destroyed, the patient will have chronic corneal abrasions. It’s an extremely challenging problem at that point.”

Dr. Gregory is a firm believer in using amniotic membrane, used in cryopreserved form as a biological bandage over the entire ocular surface. He’s now treated more than a dozen patients with amniotic membrane within the first 10 days of diagnosis, “and none have developed severe ocular problems,” he said. “Amniotic membrane doesn’t necessarily eliminate every problem that can be caused in severe cases, but we’ve been able to prevent catastrophic problems. Many have not had any significant problems once the disease has resolved.” In his hands, amniotic membrane treatment at 1 month or longer after presentation “has had limited effects in stopping the acute phase damage.”

Dr. Sippel uses amniotic membrane in the acute stage and lines the entire conjunctival surface, including the inside of the eyelids and lid margins, she said. “We’re using amniotic membrane to cover denuded ocular surfaces,” she said. “It dissolves eventually, but it gets the patient through the acute phase.”

There are no large case series in the literature, Dr. Gregory added. One of his papers examined all published case series1, and he said a multicenter study is currently being planned to pool results. At New York-Presbyterian, “We have a very low threshold for amniotic membrane application in the acute stage,” Dr. Sippel said. Dr. Sippel will also use steroids, as a recent paper advocated pulse therapy.2 “We use topical in the first few days, only for a brief time, and a very intense regimen. We’ve had good results with that, too. In general, we are super aggressive with both amniotic membrane and steroid use in the hyperacute stage,” she said.

“High dose, very short term systemic steroids can be helpful in the acute stage,” Dr. Akpek said. “Long term, it could lead to sepsis so we try to limit steroids to a week or so at the very acute stage.” “Some have tried topical treatments, and there seems to be a role for anti-inflammatory drugs in controlling SJS, but these patients need to be monitored very closely,” Dr. Gregory said. In the acute phase, this includes daily examination, looking for corneal epithelial defects that can become infected corneal ulcers. “Look for any abnormality of the tear film, on the surface of the eye, notice abnormal blinking,” he said. “These patients are usually being treated in a hospital, so they’re being exposed to more virulent organisms.”

At Johns Hopkins Hospital, treatment of SJS patients with intravenous immunoglobulin therapy is used, but “I’m not completely convinced it works. We have not yet reviewed our results,” Dr. Akpek said.

Dr. Sippel also fits patients with the Kontur Lens (Kontur Kontact Lens Co., Hercules, Calif.). “It’s a bandage contact lens that comes in sizes up to 24 mm, so it can fit all the way into the fornices and can keep two denuded surfaces apart, acting akin to a symblepharon ring” she said. Dr. Akpek uses the ProKera for milder cases (Bio-Tissue Inc., Miami), a biologic bandage that has fresh amniotic membrane in the middle, she said. “It doesn’t cover the fornices, however,” she said, so it may not be appropriate for patients with extensive conjunctival involvement. Dr. Akpek also uses cyclosporine 1% eye drops and frequent non-preserved artificial tears.

Ongoing management

In the visual rehabilitation stage, “the key is to mimic in some way the normal functions of the ocular surface,” Dr. Mannis said. “You have to ensure the lids and globe are in the appropriate anatomic relationship.”

If the disease is not severe enough to have caused scarring and vascularization of the cornea, stem cell grafting or keratoprosthesis are viable options, Dr. Mannis said. “It’s a delicate procedure, and close follow-up is necessary. We follow patients who are on immunosuppression therapy in conjunction with an internist who is helping to manage the medical therapy,” he said.

In the intermediate period, Dr. Akpek said tear ducts that are “not already closed from inflammation, I’ll permanently cauterize. There is nothing better than your own tears, but if the patient has a severe dry eye, I’ll continue to have them use artificial tears.” She may also prescribe Lacrisert (5 mg of hydroxypropyl cellulose, Aton Pharmaceuticals, Lawrenceville, N.J.), a slow-release ocular coat to help prevent the cornea from drying out. After the acute phase, Dr. Gregory said he commonly sees “abnormal position of eyelid margins, trichiasis, problems with keratinized and scarred tarsal conjunctiva that causes blink-related micro trauma to cornea. Over time, these corneas opacify. Trying to do a corneal transplant on the patient is challenging because the tear film is abnormal, there may be damage to limbal stem cells, and trying to maintain a healthy graft is extremely difficult.”

For patients with chronic ophthalmic sequelae of the disease, Dr. Sippel recommends using the Boston Scleral Lens (Boston Foundation For Sight, Boston), a fluid-ventilated gas-permeable contact lens that rests directly on the sclera to create a fluid-filled space over the diseased cornea. “It just bathes the cornea in tears, and SJS patients have horrible dry eye; if they’re in end-stage SJS, corneal scarring is likely,” she said. “The BSL can retard the process or halt scarring effectively.”

In SJS/TEN, the eyelids of patients can become “very deformed,” leading to trichiasis and/or keratinization of the lid margin, she said. When the lid margin keratin migrates over the lid, “it’s like sandpaper over the cornea. The scleral lens keeps the diseased lids away from the cornea; the problem is fitting is somewhat problematic.” She refers most of her patients to the Boston Foundation for Sight (Needham, Mass.) for proper fitting. Dr. Gregory refers all lid problems to an oculoplastics specialist. “We may use serum autologous eye drops to help with symptoms,” he said. For those with significant symptoms, he also refers patients to the Boston Foundation for Sight. When using a keratoprosthesis, Dr. Mannis tends to favor the Boston KPro (also called the Dohlman-Doane, developed at Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary, Boston).

“It can be problematic in these patients, as any prosthesis,” he said. “The normal ocular surface is deranged by the disease. Even when you’re not dealing with the surface of a corneal graft, there’s potential melting of the tissue around the prosthesis, and extrusion is high. You need to monitor these patients very, very closely, and all need contact lenses or contact lenses and tarsorrhaphy. These are very, very labor-intensive patients.”

Dr. Sippel uses the KPro “as a last resort intervention,” when patients have corneal scarring and “absolutely no tear function.” Patients “with the poorest prognosis for KPro are SJS patients,” she said. “It’s an optional last resort, where there’s nothing left for us to try, and the KPro really is the last hope for getting any kind of functional vision back.” Dr. Akpek also agrees. She saves the Boston KPro as a last resort for vision rehabilitation in these patients. Dr. Mannis cited the example of a 70-year-old woman who was functionally blind from SJS, “but for the last 4 years she’s been independent because of the KPro. It had to be replaced once, but it does afford tremendous possibilities.”

He noted there is research under way combining the use of both the KPro and stem cell grafting. “The idea is to employ stem cells to create a more normative ocular surface; if it might not support a corneal graft, it could support the KPro,” he said. Down the road, cataract surgery will became necessary in these patients who have survived SJS “and it is very hard,” Dr. Akpek said. “They have completely neovascularized corneas. I don’t do phaco on these patients, but extracap or intracap; you really cannot see anything through the scarred cornea.”

“The future of these patients will depend on advances in keratoplasty and our ability to modulate stem cells more effectively,” Dr. Mannis said. “An ongoing problem with SJS is that the media in which you place any foreign material is so hostile because of the absence of normal tear film, or lid/globe relationship. The key in finding successful treatments lie in ensuring the ocular environment is less hostile.”

Preventing as many ocular problems as possible at the onset is “crucial,” Dr. Gregory said. “We need to try and educate people that treating with amniotic membrane within the first couple of weeks of the disease makes a big difference.”

Editor’s note

Drs. Mannis, Sippel, and Gregory have no financial interests related to their comments. Dr. Akpek has received research grants from Allergan (Irvine, Calif.). for the use of topical cyclosporine.

Contact information

Akpek: 410-955-5494, esakpek@jhmi.edu

Gregory: 720-848-2500, darren.gregory@ucdenver.edu

Mannis: 916-734-6957, mjmannis@ucdavis.edu

Sippel: 646-962-3126, kcs2002@med.cornell.edu

References

- Gregory DG. The ophthalmic management of acute Stevens-Johnson Syndrome. Ocul Surf. 2008;6:87-95.

- Araki Y, Sotozono C, Inatomi T, et al. Successful treatment of Stevens-Johnson Syndrome with steroid pulse therapy at disease onset. Am J Ophthalmol. 2009 Mar 13 [epub ahead of print].