The Best Costume for Today: The Impact of Grey Gardens

Albert Maysles, David Maysles, Ellen Hovde, and Muffie Meyer, directors. Grey Gardens. Portrait Films, 1975.

The fashion world has often embraced Edith “Little Edie” Bouvier Beale as an icon of quirky, eccentric style. Beale was made famous by the 1975 documentary Grey Gardens, directed by Albert and David Maysles. In the film, she and her elderly mother, also named Edith, were captured going about their everyday lives in their decrepit East Hampton family home. As the aunt and cousin of Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, their dire, isolated living situation—they stayed in a barely habitable, 28-room mansion no longer equipped with running water, surrounded by countless cats and raccoons—was that much more shocking to the public. Despite these difficult conditions, throughout the documentary Edie demonstrated a sharp sense of style and elegance, and a remarkable ability to craft inventive outfits from her formerly fashionable clothing, which she effortlessly combined with random household items. The documentary has since inspired various fashion collections and magazine editorials, as well as a 2009 HBO adaptation starring Drew Barrymore and Jessica Lange. This essay argues that, between the documentary and these subsequent interpretations, visual focus has moved away from the aging female body and the domestic sphere and firmly onto the designer fashion commodity. This shift has occurred through changing representations of bodies and the senses, the use of specific narrative techniques, and the appropriation of aesthetic bricolage.

BODIES AND THE SENSES

When Grey Gardens was first released, it left an overwhelmingly negative impression on many reviewers, who believed that the film took advantage of its vulnerable female subjects. Writing in Vogue, which would years later celebrate the Beales as fashion icons, Charlotte Curtis declared the documentary to be “one of the most exploitative, tasteless, and frankly reprehensible films of them all, a relentless account of life as the ladies of Grey Gardens live it among the trash, tin cans, and cat dung of their once-elegant East Hampton mansion.” [1] In her review, Curtis reduced the two women’s physical state to the basic functions of human survival: “They eat when they are hungry and sleep when they’re tired. Any sort of cleanliness is beside the point,” and argued that the film portrayed them in their “final deterioration.” [2] Her observations appear to conflate the women’s bodies with the domestic space they inhabited, with the decaying state of the house transposed onto them. The author referred to Edie as being physically healthy in one sentence, and announced her deterioration in another. Curtis also compared the way the younger Beale had styled her skirt, in one of the movie’s most famous scenes, to a diaper.

The New York Times review also found the film distasteful and centered much outrage on the portrayal of the Beales’ bodies on camera. The male reviewer described a scene where Edith “raises her arms, flabby and creased” and recounted how one of her outfits left “her hair covered, her legs exposed well up the heavy thighs.” He lamented the sight of “the sagging flesh, the ludicrous poses” and, like Curtis, claimed that the film illustrated “the remnants of two lives expiring in a haze,” [3] despite the fact that throughout the documentary Edie appears to be quite energetic in front of the camera. Both of these accounts, printed in major publications, communicated specific standards of respectability that the two women failed to meet, and that the filmmakers unethically brought to light.

“She is aware of the multiple gazes placed on her and she actively gazes back.”

In the documentary the women do not shy away from discussing their bodies and the process of aging. Edie, especially, is always in charge of the image she projects to the viewer. She is aware of the multiple gazes placed on her and she actively gazes back, frequently addressing the filmmakers outside the camera’s frame. She also speaks openly of the work required to present herself onscreen: she expresses the need to put on makeup, weighs herself, and conspicuously adjusts her clothes in front of the camera. All of these gestures highlight the labor required for women to be acceptable cinematic subjects, in both documentary and fictionalized form. In addressing these things candidly, Edie takes control of the process of her self-representation. As argued by Matthew Tinkcom, she actively assumes the position of both subject and object of the cinematic gaze, which “bestows upon her a sense of presence offered to few women in the more conventional regimes of gendered viewing in the cinema.” [4]

Film theorists Christian Metz and Noël Burch argue that a minimum gap or distance is required for voyeurism to be effective in film. [5] Grey Gardens, in documentary form, is chaotic and loud. In it, sound plays an important role. The women are constantly yelling, arguing, singing, playing music, and chasing animals around the house. In the documentary, visual and sound techniques are destabilizing. Shot in the direct cinema style, the camera work is often shaky, fragmented, moving between close-up shots of the women’s bodies and scenes depicting the house’s chaos, and establishing a visual connection between the two, something that comes through in early reviews of the film. Senses, more broadly, play an important role in it. The two women often eat onscreen, in the cluttered, filthy room they share. They bicker loudly about sex and Edie often asks her mother to cover up for the camera (drawing a clear line between acceptable private and public behaviors). Commenting on the smell in her bedroom, the older Edith defiantly claims: “I’m not ashamed of anything. Where my body is, is a very precious place.”

Anna Rogers Backman recognizes just how challenging the film was for a contemporary audience precisely because of this lack of distance or clear separation between viewer and film subject, where it was difficult to designate the “other” from the audience. [6] The documentary positions the two women as figures of spectacle, in a familiar yet strange setting, provoking an uneasy fascination for viewers who have difficulty consuming these images in a passive way. The original film prompted many ethical questions and reflections—around the two women’s bodies, their physical and mental state, their place in society—that subsequent visual representations of them do not require. These kinds of embodied references are lost in future iterations of the movie and in the women’s fashionable images, which are much easier to engage with.

NARRATIVE TECHNIQUES

In the 1975 documentary the narrative is chaotic, non-linear, and dictated almost entirely by the women through personal stories, arguments, and old photographs. In the HBO film, on the other hand, the story is coherent and sequential. The dramatized film also positions Edie as a legitimate actor and tastemaker in a capitalist fashion system. It shows her working as a model in New York City in her younger days, wearing the latest fashions and attending lavish parties, including one at Grey Gardens at the height of its bohemian fashionability.

Michael Sucsy, director. Grey Gardens. HBO Films, 2009.

The film presents her through a deliberate fashion-historical lens, using visual language similar to that of magazine editorials and fashion photography. At one point, Drew Barrymore as Edie surprises a news photographer on the Grey Gardens property, and invites him to take photos of her in her signature fur coat outside the house, as well as portraits of her and her mother inside. The scenes depicting Edie in New York are clear attempts at establishing her (former) fashion credentials. When Edie first arrives in the big city, wearing a very fashionable 1930s ensemble, she stops to look at a window display and catches her reflection—the resulting shot is a clear nod to the work of photographers like Lisette Model and Lee Miller. Through an act of historical, visual bricolage, the film is able to concretely illustrate Edie’s fashionable past and confirm that she was once a fashion insider, with the appropriate knowledge to legitimize her current eccentricities. The costume designer for the HBO film, in a 2009 interview with The New York Times, made sure to remind readers that Edie “wasn’t always a totally wacky dresser, although she had her own sensibility about dressing.” [7]

The HBO film is noticeably more image-driven than the documentary: the Beales’ story is presented as a series of ordered, visually pleasing tableaux that illustrate the women’s progressive downfall from high society to domestic isolation. These techniques make Edie’s image as an older woman less jarring than in the documentary. The contrast between her youthful appearance (fashionable, thin, beautiful) and her current state (unfashionable, heavier, anxious, suffering from hair loss that she needs to conceal with her signature headscarves) is framed within a coherent narrative that covers everything from the women’s mysterious, wealthy, glamorous past, to their unfortunate present. The chaotic and complex relationship between the two women feels much less visceral and embodied than in the documentary.

Michael Sucsy, director. Grey Gardens. HBO Films, 2009.

Thomas Elsaesser and Malte Hagener use the metaphors of the window and door to describe different cinematic experiences. [8] In that sense, the documentary serves as a door into the private, transgressive space of these women (allowing the viewer to cross the threshold between acceptable and unacceptable female representation), whereas the HBO film is more of a window into a neatly arranged series of memories, events, places, and characters. In the HBO film, fundamentally, the women are not as engaged in their image-making process. Their social decline and, therefore, their accelerated aging and loss of beauty and elegance is something that happens to them because of their fall from society, as well as a perceived lack of male attention and support. Men and their associated social, emotional, and economic power are shown to be crucial catalysts in the women’s increasing isolation (and, as a result, their changing appearances).

DOMESTIC SPACE AND BRICOLAGE

Michel de Certeau defines space as a practiced place—he explains that the familiar places where people live are sites where enigmatic, fragmented, private stories unfold, and are symbolized in the body’s pain or pleasure. De Certeau also defines bricolage as the act of making do with available resources, combining and adapting everyday objects and materials in a makeshift fashion, rather than creating or buying something new. [9] Bricolage, then, is basically an anti-capitalist exercise. In the documentary, the women constantly repurpose their space (cooking in bed for guests, making creative use of various household objects, using photos and records to remember their past). Edie wears a cardigan as a skirt and a bath towel as a headscarf. There is a strong connection between bodies, memories, and the domestic space.

Albert Maysles, David Maysles, Ellen Hovde, and Muffie Meyer, directors. Grey Gardens. Portrait Films, 1975 (source: imdb).

As a viewer, it is important to remember that Edie was living completely outside of the fashion system when the documentary was made. Her everyday was a fashion statement, so there was a lot of agency in her image-making. In the 1975 documentary, Edie’s creative outfits represented a way for her dress up, to escape the monotony of daily life. In the HBO movie, based on the narrative and images of her former life, they could be viewed as a form of dressing down, the visual consequences of a living situation she had ultimately ended up in, but could still escape. In a classic scene from the documentary Edie describes her “revolutionary costume”:

This is the best thing to wear for today, you understand. Because I don’t like women in skirts. And the best thing is to wear pantyhose or some pants, under a short skirt, I think. Then you have the pants under the skirt, and then you can pull the stockings up over the pants, underneath the skirt. And you can always take off the skirt and use it as a cape. So I think this is the best costume for today... I have to think these things up, you know...

Her declaration that she has to “think these things up” signals creativity, her potential to be a fashion tastemaker, but also suggests that this talent is dictated by her everyday situation and the constraints — financial, social, emotional — it imposes on her. Edie, as an individual, used elements of deconstruction and re-appropriation in her clothing, long before these practices were theorized as high fashion by avant-garde designers, the press, and fashion academics. Just as “deconstructionist” designers would attempt to do in the 1980s and 90s, Edie’s clothing served to “reconcile the oppositions of new/old, rich/poor, masculine/feminine, that are continually reasserted in visual culture.” [10] In recent years, this exercise has been re-appropriated by high fashion designers, with Edie’s image increasingly being used to market luxury garments.

Vogue España, October 2010, photographed by Mark Seliger (source: http://grey-gardens.tumblr.com/post/22473594573/the-november-issue-of-vogue-spain-contains-an).

IN VOGUE

HBO’s Grey Gardens, along with fashion collections and Vogue editorials inspired by the Beales, deliberately position the two women as bohemian characters, a common motif in fashion. According to Elizabeth Wilson, “[c]omponents of the [bohemian] myth are transgression, excess, sexual outrage, eccentric behavior, outrageous appearance, nostalgia and poverty.” [11] These elements are found in adaptations of the Beales on both film and the pages of fashion magazines, and contribute to establishing their brand of offbeat glamour. Tinkcom describes the Beale women, in the documentary, as being “by turns enchanting and compelling but also distant and ultimately unknowable,” [12] which defines a specific type of glamour. The word glamour, in its Latin and Scots origins, refers to notions of mystery, the occult, and magic, and in Greek suggests something that is hidden. [13] Imagination, departure from convention, and uniqueness of character are crucial to the making of the glamorous individual. [14] In the HBO movie and mainstream fashion images, glamour resides in material luxury objects and their visual consumption by an audience, rather than in the uniqueness and agency of its subjects.

In fashionable interpretations of Edie’s image, her surroundings, so formative to the creation of her original wardrobe, transition away from material hardship and into a playful, elegant clutter, a collection of bric-a-brac that is not closely connected to the body and does not have a real relationship to the wearer’s everyday life. In these images, bodies are on display as vehicles of fashion rather than as a scene of fashion performance.

Vogue, September 2005, photographed by Tim Walker (source: The Vogue Archive).

In a 2010 Spanish Vogue editorial, the model is carefully styled as a prop, in rooms that are full of objects arranged like a deliberately messy cabinet of curiosities. The model becomes part of the décor while remaining completely static, and somehow does not interact with the disarray around her. In The Fashion System, Roland Barthes defines the “Fashion Woman” as “an ideal figure who does not concern herself with money; on the magazine page she never has to deal with any of life’s “defects and difficulties.” [15] The contrast between the model’s glamorous clothes and jewels, her disconnected poses, and the materiality of her surroundings exemplifies this ideal.

References to Edie in a 2013 Vogue Paris editorial can be found in the layering, print mixing, headscarves, and binoculars worn by model Erin Wasson. She is pictured in the desert looking like an adventurer, wearing a combination of socks and sandals and inexplicably, holding a broom. Here, the theme of the “eccentric” older lady is transposed to the body of a young model sent into a remote, unfamiliar locale; she is part intrepid adventurer, part older woman. The socks/sandals combination illustrates the connection that many designers and stylists seem to make between Edie and shabbiness, or unkemptness—best expressed, naturally, with designer garments—even though her image was always very put together (the only shoes she is ever seen wearing in the documentary are high heels).

Cats have also become an easily recurring, somewhat lazy motif in most Grey Gardens-referencing fashion imagery. It that seems any standard editorial, with the addition of cats, a country house, and vague references to the passing of time, can become an homage to Grey Gardens.

The bizarre introduction to a 2008 recession-era Vogue editorial encourages a certain level of creativity and discernment from readers during the financial crisis:

The urge to go out and buy something is an essentially life-affirming one. And in an era when the dollar is—how can we put this politely?—not what it once was, it takes determination as well as optimism (and means) not to stay at home and make do and mend. [16]

Vogue, January 2008, photographed by Steven Meisel (source: The Vogue Archive).

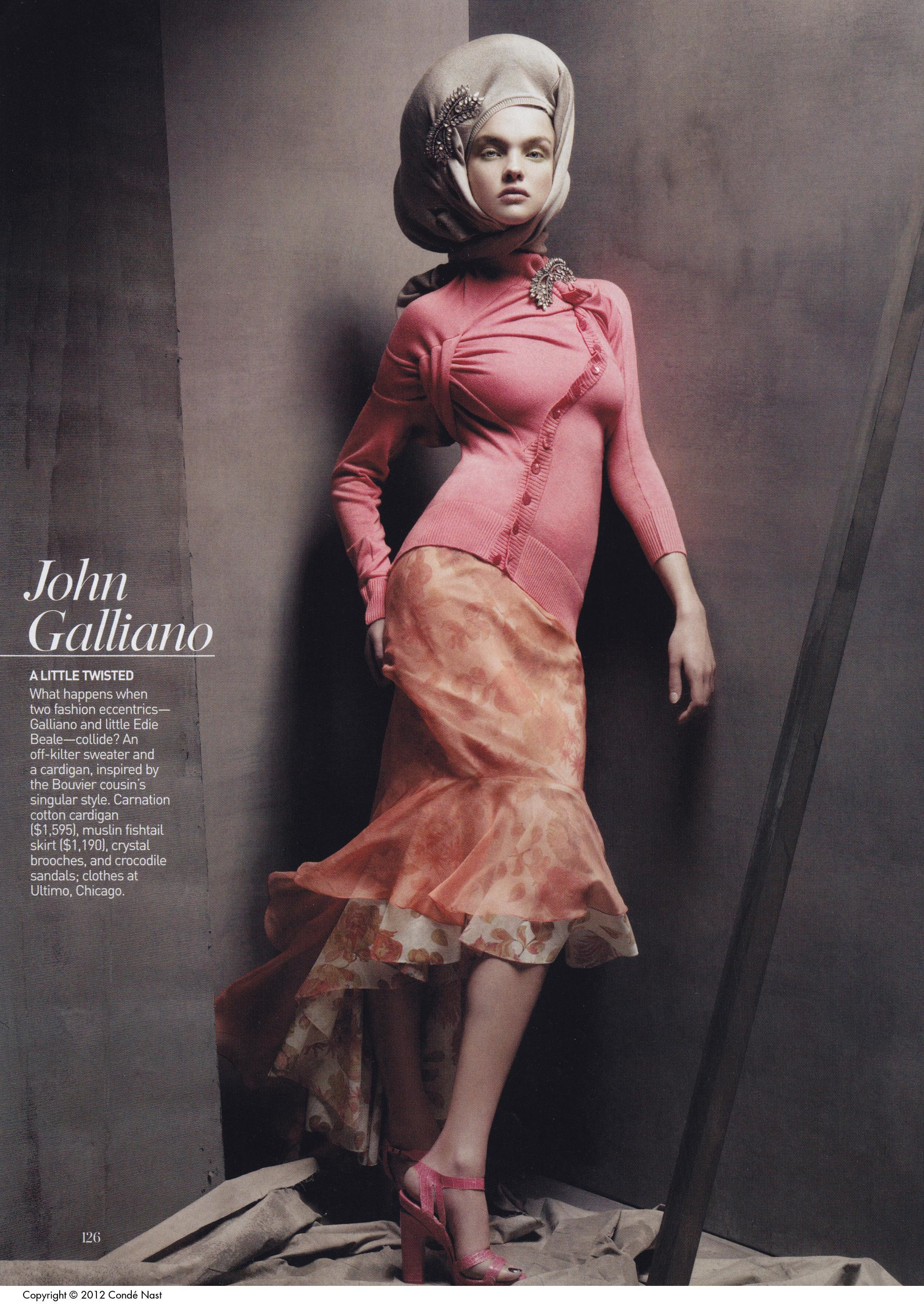

Here the author makes an explicit reference to bricolage, to making do with one’s own possessions when times are tough. However, she contrasts this practice with the more desirable, life-affirming activity of high fashion consumption. The editorial includes one look inspired by Edie, titled “A Little Twisted,” described as follows: “What happens when two fashion eccentrics—Galliano and little Edie Beale—collide? An off-kilter sweater and a cardigan, inspired by the Bouvier cousin’s singular style.” [17] The model wears a brightly colored cardigan and skirt, priced at $1,595 and $1,190 respectively, along with a turban. There is a complete disconnect between what is promoted by the author—the requisite “determination” and “optimism” to continue spending money on fashion during a recession—and the inspiration for this look, a woman who had no choice but to actually make do and mend in order to craft the personal image that became so beloved by designers such as Galliano.

This particular ensemble was part of Galliano’s Spring 2008 ready-to-wear collection, which was inspired by the Beales, and shown in a carnivalesque runway setting. Reviewing the collection, Vogue’s Sarah Mowers commented dismissively that his “tale of faded flapperdom and eccentric cat-loving aristocratic decay is one of the most hackneyed fashion references of recent times.” She continued: “Then a segue into demented Little Edie head-swathed cardigan looks, and a cat-fur-sprouting chubby to make the theme obvious.” [18] Like other designers who claim to be inspired by Edie, the connections to her image in this specific collection were vague, and relied on the same basic, often-repeated elements: headscarves, cats, colorful mixed patterns, and obligatory references to female eccentricity. Mowers lamented the unimaginative nature of Galliano’s referencing, but by calling the Edie-inspired outfits “demented,” she also reduced her to a very problematic cliché, and her critical review did not stop the clothes from eventually finding their way onto the magazine’s pages in an awkwardly-timed appeal to high fashion consumerism.

CONCLUSION

In 1975 The New York Times referred to the Beale women as grotesque, arguing that the film portrayed them as a circus sideshow. Whether positive or negative, these visual theatrics were performed by the two women themselves. In high fashion iterations of Grey Gardens, spectacle is entirely represented by clothes that are either banal or overly dramatic, styled in carnivalesque settings, and disconnected from their wearers. David Adair and Annita Boyd argue that “the Edies resisted all attempts to contain them, thereby achieving a more revolutionary outcome than carnival would ordinarily allow,” [19] but the fashionable co-optation of these performances—which were once individual, and situated within specific bodies and locations—has turned their image into a completely different visual commodity.

Like many counter-cultural figures before and after her, Edie’s style has been reduced to a series of simplistic signs and placed back into the normative fashion codes that she so expertly adapted and fundamentally challenged. Her story has been recounted through progressively younger, disengaged bodies that do not gaze back at the camera or the spectator in the same way.

Fashion designers and the media have repositioned Edie’s unique brand of glamour firmly back into the realm of conventional, material, capitalist glamour. Different visual techniques, from the cinema to the fashion page, have transposed her aesthetic from an aging body to an ageless one, from the everyday/domestic to the sensational and public. Edie’s image is now used to re-affirm traditional splendor and, more importantly, spending. Just as Edie’s outfits were an exercise in bricolage, based on specific life circumstances, fashion bricoleurs have reconstructed her image, extracting from it quickly-recognizable signs of female eccentricity that serve as a testament to the creative genius of the star fashion designer rather than the wearer herself. As a result, the creative labor of the wearer and any element of counter-visuality have been completely lost. The purely aesthetic high fashion interpretations of Edie’s image have absolutely no relation to the lived experience of the woman who inspired them.

It is important to pause and think about what we—and fashion commentators—are celebrating when we talk about Edie’s whimsical, “off-kilter” style. As reactions to Edie’s image have shifted throughout the years, it appears that the glamorous secret, the unknown, are very appealing to audiences, but only if they can be consumed in visually appealing ways, quickly, and at a distance. It is worth noting that the Grey Gardens property, restored in recent years, is now owned by Liz Lange, a New York City-based fashion designer who “had long been captivated by the decaying mansion and its eccentric former residents.” [20]

Notes

[1] Charlotte Curtis, “People Are Talking About: Grey Gardens,” Vogue, November 1975, 192.

[2] Ibid., 243.

[3] Walter Goodman, “‘Grey Gardens’: Cinéma Vérité or Sideshow?” The New York Times, February 22, 1976, D15, 19.

[4] Matthew Tinkcom, Grey Gardens, BFI Film Classics (Houndmills, Basingstoke; New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011), 66-67.

[5] In Mary Ann Doane, “Film and the Masquerade: Theorising the Female Spectator,” in Feminism and Film, ed. E. Ann Kaplan (Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press, 2000), 423.

[6] Anna Rogers Backman, “The Crisis of Performance and Performance of Crisis: The Powers of the False in Grey Gardens (1976),” Studies in Documentary Film 9, no. 2 (2015): 117.

[7] In Eric Wilson, “Exploring the Style Behind ‘Grey Gardens’,” New York Times, April 15, 2009 (online).

[8] Thomas Elsaesser and Malte Hagener, Film Theory: An Introduction Through the Senses(London: Routlege, 2010).

[9] Michel de Certeau, The Practice of Everyday Life (Berkeley; London: University of California Press, 1984), 66, 108.

[10] Rebecca Arnold, Fashion, Desire and Anxiety: Images and Morality in the 20th Century (London; New York: I.B. Tauris, 2001), 22.

[11] Elizabeth Wilson, Bohemians: The Glamorous Outcasts (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2000), 5-6.

[12] Tinkcom, Grey Gardens, 81-82.

[13] Elizabeth Wilson, “A Note on Glamour,” Fashion Theory 11, no. 1 (2007): 95; Carol S. Gould, “Glamour as an Aesthetic Property of Persons,” The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 63, no. 3 (2005): 238.

[14] Wilson, “Glamour,” 98; Gould, “Glamour,” 246.

[15] Roland Barthes, The Fashion System (New York: Hill and Wang, 1983), 261.

[16] “Vogue Point of View: Peerless,” Vogue, January 2008, 116.

[17] Ibid., 126.

[18] Sarah Mowers, “John Galliano Spring 2008 Ready-to-wear,” Vogue, October 5, 2007 (online).

[19] David Adair and Annita Boyd, “Returns from the Margins: Little Edie Beale and the Legacy of Grey Gardens,” Film, Fashion & Consumption 2, no. 1 (2013): 40.

[20] Kara Meyer Robinson, “Sunday at Grey Gardens with Liz Lange, Fashion Designer,” New York Times, July 31, 2015 (online).