An Epidemiological Meta-Analysis on the Worldwide Prevalence, Resistance, and Outcomes of Spontaneous Bacterial Peritonitis in Cirrhosis

- 1Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University Singapore, Singapore, Singapore

- 2Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Medicine, National University Hospital, Singapore, Singapore

- 3Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Department of Medicine, National University Hospital, Singapore, Singapore

- 4National University Centre for Organ Transplantation, National University Hospital, Singapore, Singapore

Background and Aims: Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP) is a common and potentially fatal complication of liver cirrhosis. This study aims to analyze the prevalence of SBP among liver cirrhotic patients according to geographical location and income level, and risk factors and outcomes of SBP.

Methods: A systematic search for articles describing prevalence, risk factors and outcomes of SBP was conducted. A single-arm meta-analysis was performed using generalized linear mix model (GLMM) with Clopper-Pearson intervals.

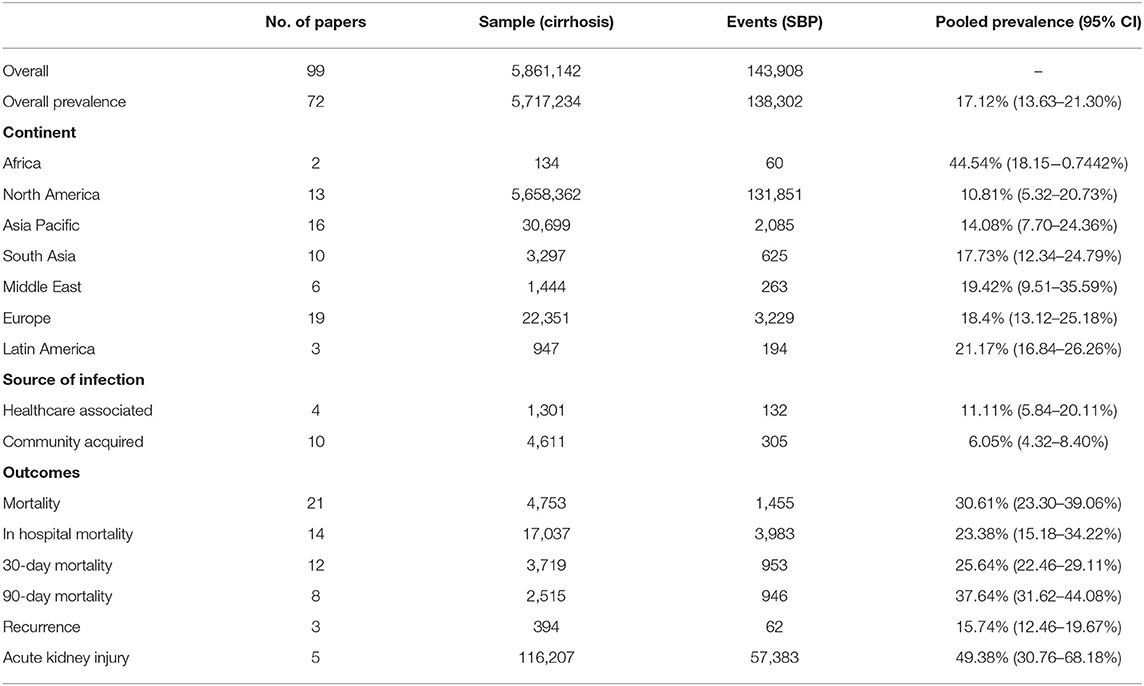

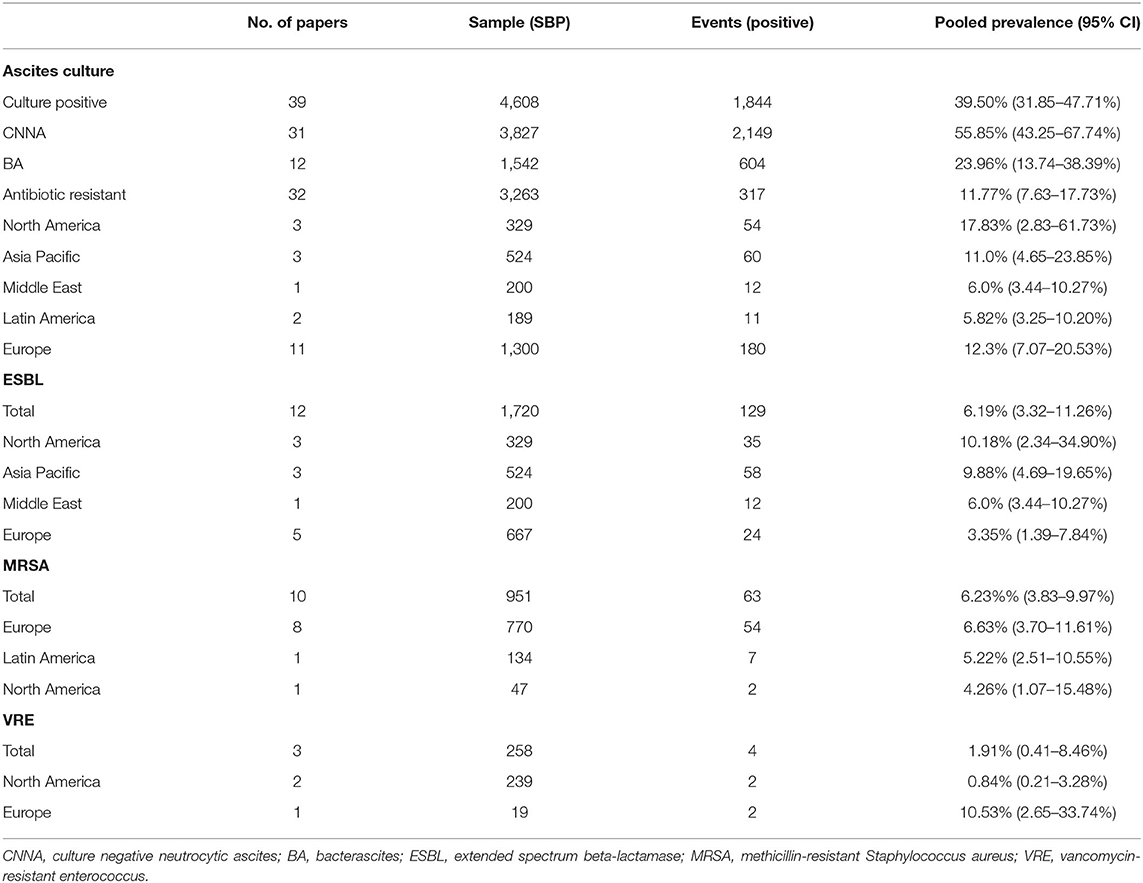

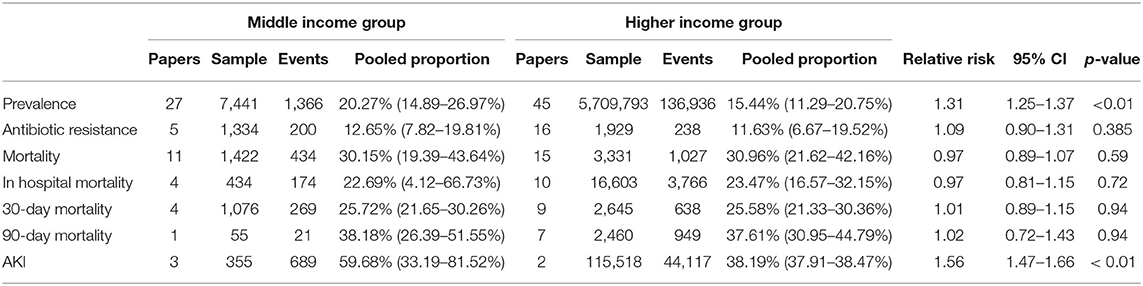

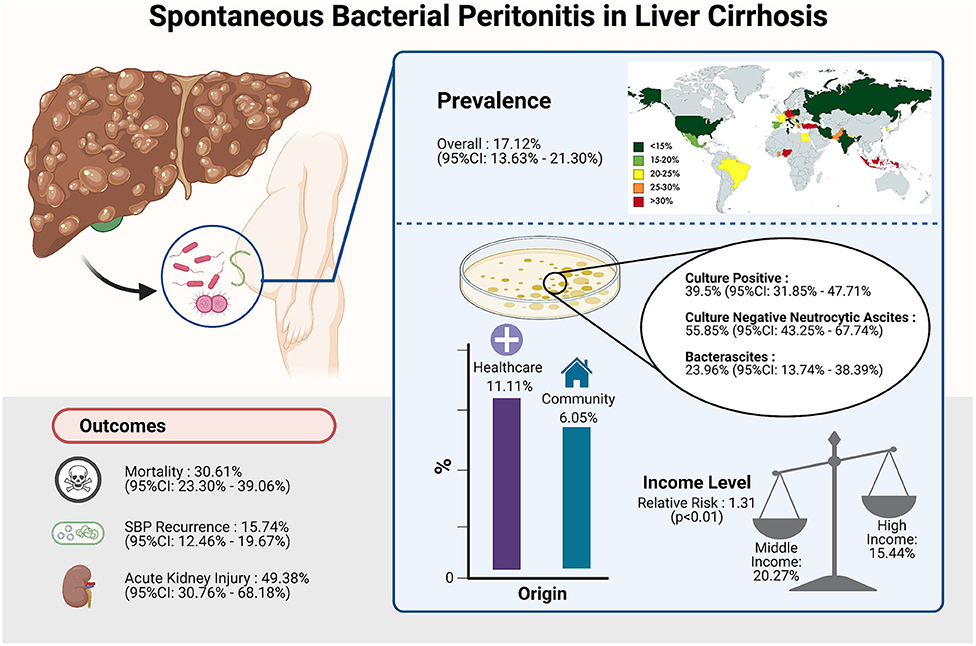

Results: Ninety-Nine articles, comprising a total of 5,861,142 individuals with cirrhosis were included. Pooled prevalence of SBP was found to be 17.12% globally (CI: 13.63–21.30%), highest in Africa (68.20%; CI: 12.17–97.08%), and lowest in North America (10.81%; CI: 5.32–20.73%). Prevalence of community-acquired SBP was 6.05% (CI: 4.32–8.40%), and 11.11% (CI: 5.84–20.11%,) for healthcare-associated SBP. Antibiotic-resistant microorganisms were found in 11.77% (CI: 7.63–17.73%) of SBP patients. Of which, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus was most common (6.23%; CI: 3.83–9.97%), followed by extended-spectrum beta-lactamase producing organisms (6.19%; CI: 3.32–11.26%), and lastly vancomycin-resistant enterococci (1.91%; CI: 0.41–8.46%). Subgroup analysis comparing prevalence, antibiotic resistance, and outcomes between income groups was conducted to explore a link between socioeconomic status and SBP, which revealed decreased risk of SBP and negative outcomes in high-income countries.

Conclusion: SBP remains a frequent complication of liver cirrhosis worldwide. The drawn link between income level and SBP in liver cirrhosis may enable further insight on actions necessary to tackle the disease on a global scale.

Introduction

Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP) is the development of bacterial infection in the peritoneum, with no apparent intra-abdominal source of infection (1). According to the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) practice guidelines (2), diagnosis of SBP is made in the presence of elevated ascitic fluid polymorphonuclear (PMN) leukocyte count ≥250 cells per mm3, although infection can also be diagnosed when patients are ascitic fluid culture positive with PMN <250 cells per mm3. SBP is the most common bacterial infection of cirrhosis and ascites with an estimated prevalence of 10–30% (3), and accounts for 4% of cirrhosis-related emergency department visits (4–8). However, outcomes of SBP in cirrhotic patients remain unfavorable. Patients with SBP have elevated risks of developing hepatic encephalopathy, sepsis and renal failure resulting in mortality rates twice that of their uninfected cirrhotic counterparts (9–11).

The exact pathophysiological mechanisms underlying SBP in cirrhosis remain uncertain. It has been theorized to be the result of intestinal bacterial translocation, evidenced by the frequent isolation of gram-negative enteric organisms in patients' ascitic fluid (7, 12). Impaired host immunity and gut microbiome changes such as overgrowth and dysbiosis have been identified as major contributory factors (4, 13). This abnormal gram-negative bacterial overgrowth is suspected to be the consequence of diminished intraluminal bile salts and small intestine mobility (3). Structural abnormalities in the intestinal mucosal wall including wider intracellular spaces, edema, and vascular congestion due to portal hypertension may also account for increased intestinal permeability (14). Immune dysfunction involves hypoalbuminemia as a result of portosystemic shunts in cirrhosis, which may result in compromised humoral and cell-specific immunity (11, 15). Severe acute or chronic liver disease is often accompanied by impaired neutrophilic and reticuloendothelial systems, further increasing susceptibility to infection (16).

However, there has yet to be an integrated analysis of prevalence, risk factors and outcomes of SBP in cirrhotic patients across different populations. Thus, this meta-analysis aims to investigate the prevalence of SBP among cirrhotic patients and explore common risk factors and outcomes correlated with SBP. Lastly, we seek to compare the prevalence, antibiotic resistance profile, and outcomes between different income groups.

Methods

Search Strategy

This review adheres to Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) guidelines for its synthesis (17). Articles relating to SBP were searched for via two electronic databases, Medline and Embase, on 13 November 2020. The search strategy utilized was: [(spontaneous adj3 bacterial adj3 peritonitis).tw.] AND [exp Liver Cirrhosis/or ((hepatic or liver) and (fibrosis or cirrhosis or cirrhotic)).tw.] AND [exp incidence/or exp prevalence/or exp epidemiology/or (inciden* or preval* or epidemiol*).tw.] All references were imported into EndNote X9 for removal of duplicates, and subsequent screening of titles and abstracts.

Eligibility and Data Extraction

The main inclusion criteria of articles were the description of the prevalence of SBP in liver cirrhosis. Only articles with a clinical diagnosis of SBP as positive ascitic fluid culture or ascites fluid analysis with PMN ≥250 per mm3 were included (10). Articles that were published before the year 2000 or without clear definitions of SBP were excluded. We included studies with designs including retrospective cohorts, prospective cohorts and cross-sectional studies. Only original studies were included. Commentaries, editorials, reviews, and non-English language publications were excluded. Two authors (PT and JX) independently performed the title and abstract sieve and full-text review based on the inclusion criteria. Discrepancies were resolved by consensus, or through the decision of a third independent author.

Relevant data were extracted into a structured proforma, including information such as country of study, continent, income level, patient characteristics, prevalence of SBP, outcomes, ascitic fluid culture, and source of infection. Extraction of information was done by six authors (PT, JX, CN, DT, YL) in blinded pairs. Outcomes of interest included the pooled prevalence of SBP in cirrhotic patients, prevalence of culture-positive SBP, origin of infection (healthcare-associated vs. community-acquired), presence of antibiotic-resistant organisms in culture-positive SBP, risk factors and outcomes associated with SBP. Included studies defined community-acquired SBP as occurring within 72 h of admission to the hospital, and healthcare-associated SBP as occurring in patients who were hospitalized in the preceding 90 days of current admission (18, 19). In studies that reported the presence of antibiotic-resistant organisms, they were classified as having methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL), or vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus (VRE) where available. The main clinical outcomes of SBP studied in this meta-analysis were overall mortality, in-hospital mortality, 30-day mortality, 90-day mortality, SBP recurrence, and acute kidney injury (AKI). SBP diagnosis included: (i) culture-positive neutrocytic ascites (CPNA), defined as positive ascitic bacteria culture and ascitic fluid PMN ≥250 cells per mm3, (ii) culture-negative neutrocytic ascites (CNNA), defined as a negative ascitic culture with PMN ≥250 cells per mm3, and (iii) bacterascites (BA), which was defined as a positive ascitic fluid culture with PMN <250 cells per mm3 (20).

Statistical Analysis and Quality Assessment

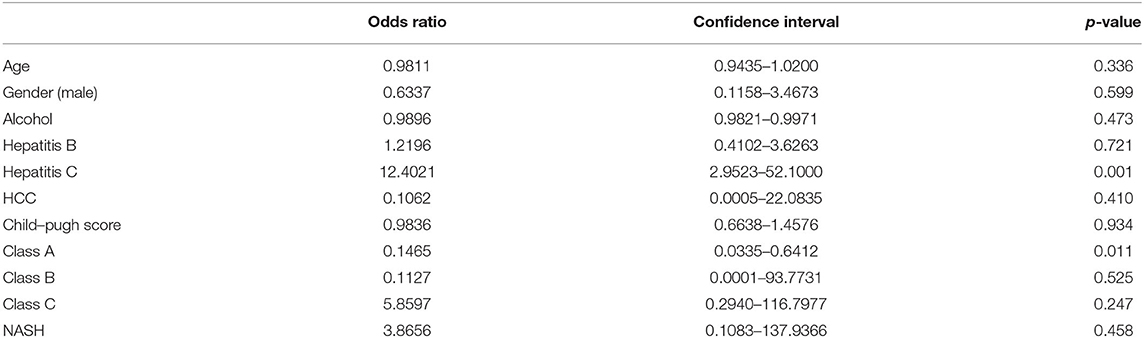

A single-arm random-effects model was used in all analyses. The generalized linear mix model (GLMM) with Clopper-Pearson intervals to stabilize the variance has been demonstrated to offer the most accurate estimate in single-arm meta-analysis (21). Statistical heterogeneity was assessed via I2 and Cochran Q test values, where an I2 value of 25, 50, and 75% represented low, moderate, and high degree of heterogeneity, respectively (22, 23). A Cochran's Q-test with p ≤ 0.10 was considered significant for heterogeneity. Regardless, all analysis was conducted in random effects model. Publication bias was not assessed in view of the lack of a tool to measure publication bias in single-arm meta-anaylsis (24). To adjust for baseline demographics including age, gender, alcoholic cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), Child-Pugh Score, and Child-Pugh Score Classes A, B, and C on the prevalence of SBP, a univariate fractional logistic model with a robust variance estimator was conducted. A subgroup analysis was also conducted to compare the prevalence of SBP based on individual geographical regions and countries with a subsequent illustration on the global prevalence using the rates from individual countries.

Next, a comparison was made between middle and high-income countries using the World Bank classification (25, 26). The individual proportions of the middle (p1) and high income (p2) countries were pooled for outcomes relating to prevalence of SBP, prevalence of antibiotic-resistant SBP, mortality, in-hospital mortality, 30-day mortality, 90-day mortality, and prevalence of acute kidney injury (AKI). Then risk ratios were calculated from the division of individual groups (p1/p2) with the lower (LCI) and upper (UCI) bound of the confidence interval estimated from the Katz-logarithmic method (27–29). The p-value was calculated after a natural log transformation of the relative risk z-score (27). Quality assessment of included studies was conducted with a risk of bias tool by Hoy et al. consisting of 10 items that address both internal and external validity. The studies were categorized into high, moderate, or low risk of bias (30).

Results

Summary of Included Articles

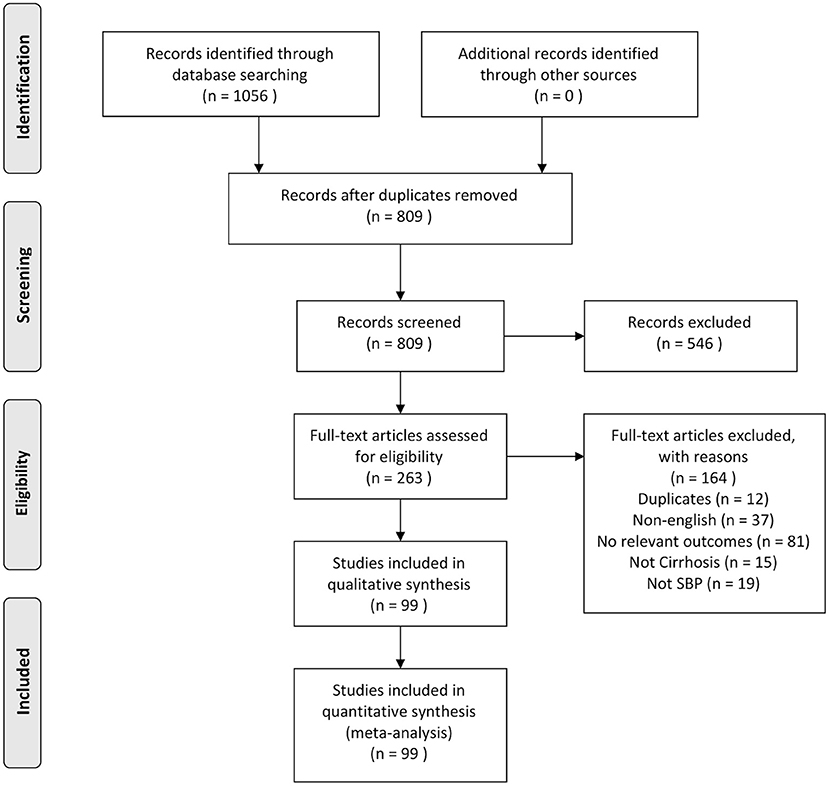

Using our search strategy, an initial 811 abstracts were identified. Duplicates were removed and 548 articles were excluded based on titles or abstracts. Two hundred sixty-three articles were eligible to undergo full-text review, of which 164 were excluded as they did not meet the inclusion criteria. A detailed description of the selection process is shown in Figure 1. In all, 99 articles were included in the systematic literature review and meta-analysis consisting of a total of 5,861,142 participants. The included studies were conducted across 7 regions, as per World Bank definitions (25), representing 29 countries, with the USA contributing to the largest number of studies (n = 11). The studies were from Europe (n = 33) (5, 31–61), Asia Pacific (n = 21) (62–82), South Asia (n = 16) (9, 83–96), North America (n = 14) (10, 97–108), Middle East (n = 8) (7, 109–115), Latin America (n = 5) (116–120), and Africa (n = 2) (4, 6). All included papers defined the diagnostic criteria of SBP to be positive ascitic fluid culture or ascitic fluid analysis with PMN count ≥250 cells per mm3. A summary of included articles is provided in Supplementary Table 1. Quality assessment shows that majority of the included articles1 had a low (74.8%) or medium (25.3%) risk of bias.

Prevalence of SBP

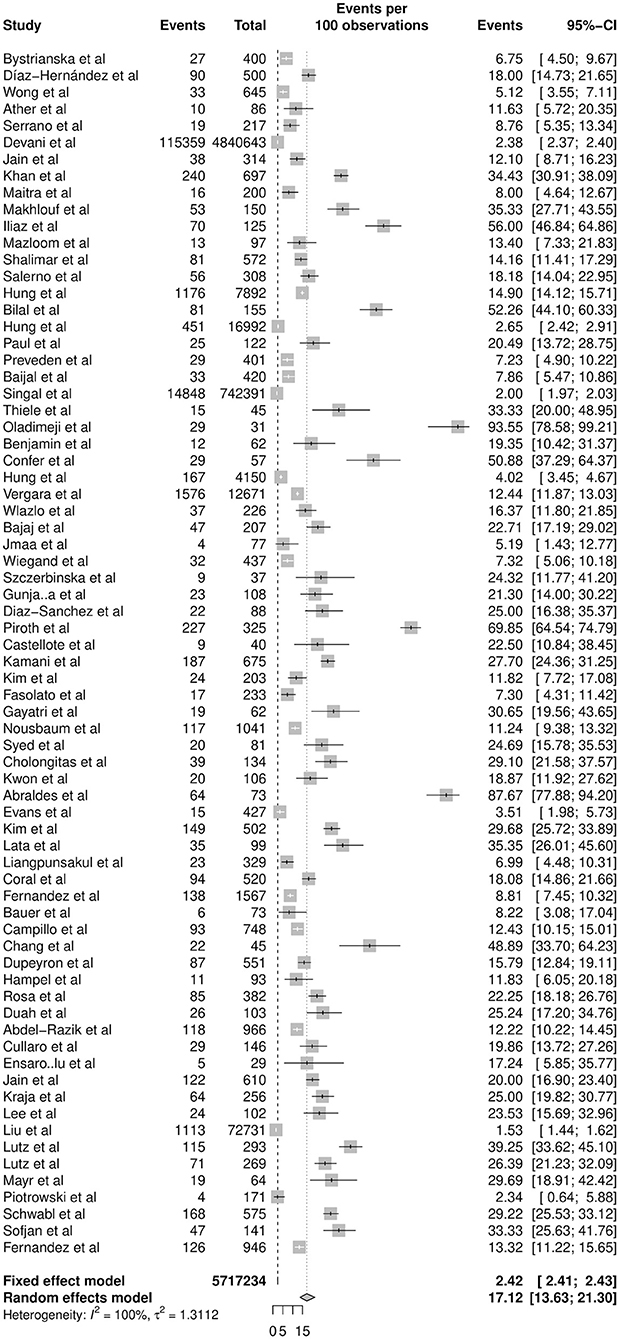

In a total of 5,717,234 individuals with cirrhosis, the overall pooled prevalence of SBP was 17.12% (CI: 13.63–21.30%, Figure 2). A fractional regression analysis was then conducted to adjust for risk factors such as age, male gender, alcoholic cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma, Child-Pugh Score, and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis on the prevalence of SBP and summarized in Table 1. The pooled prevalence of community-acquired SBP among patients with cirrhosis was 6.05% (CI: 4.32–8.40%), compared to 11.11% (CI: 5.84–20.11%) for healthcare-associated SBP.

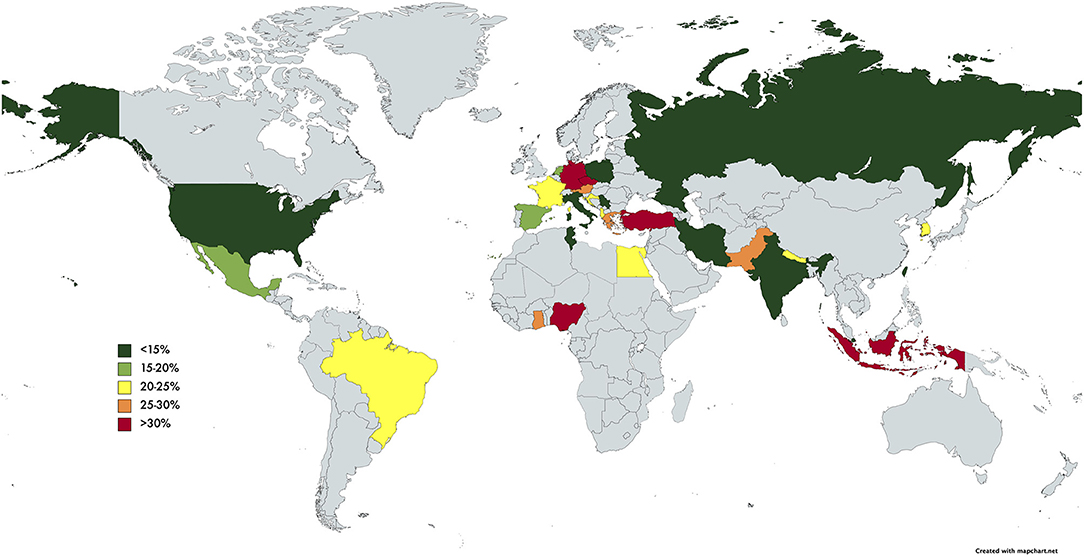

The pooled prevalence of SBP of the individual countries was represented in Figure 3. The highest rate of SBP was observed to be in Nigeria (93.55%; CI: 77.58–98.38%) and lowest in Singapore (5.12%; CI: 3.66–7.11%). Subsequently, a subgroup analysis was performed to investigate the prevalence of SBP stratified by geographical locations (Table 2). According to region, Africa had the highest pooled prevalence of 68.20% (CI: 12.17–97.08%), while North America had the lowest (10.81%; CI: 5.32–20.27%). The pooled prevalence of SBP in the Asia Pacific region was 14.08% (CI: 7.70–24.36%), 17.73% (CI: 12.34–24.79%) for South Asia, 19.42% (CI: 9.51–35.59%) for Middle East, 18.40% (CI: 13.12–25.18%) for Europe, and 21.17% (CI: 16.84–26.26%) for Latin America.

Ascitic Culture and Antibiotic Resistance of SBP

From a pooled analysis of 4,608 SBP patients, 39.50% (CI: 31.85–47.71%) of these patients had culture-positive ascitic fluid. In analysis of 3,827 SBP patients, CNNA had a prevalence of 55.85% (CI: 43.25–67.74%). Bacterascites accounted for 23.96% (13.74–38.39%) of SBP diagnosis.

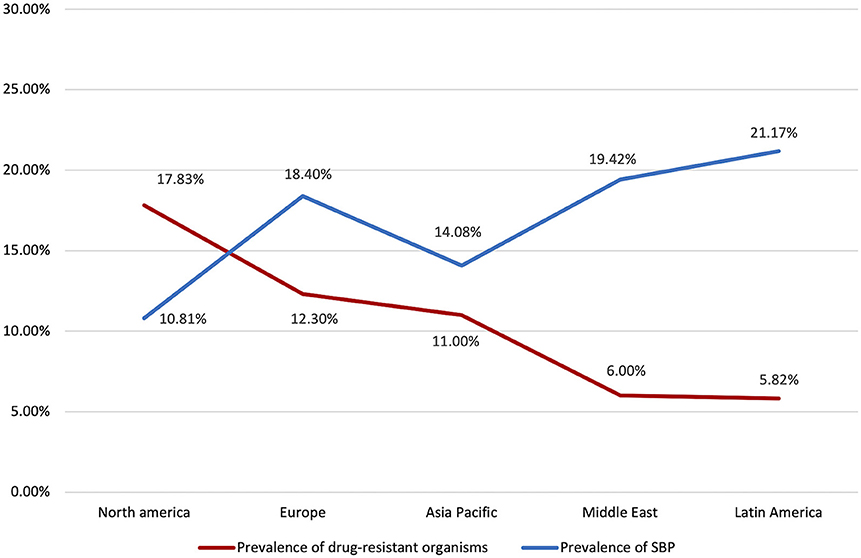

The distribution of drug-resistant organisms by geographical region is detailed in Table 3 and Figure 4. Antibiotic resistant microorganisms were found in 11.51% (CI: 7.28–17.74%) of SBP patients. In relation to regional differences, North America had the highest prevalence of antibiotic resistant pathogens (17.83%; CI: 2.83–61.73), followed by South Asia (16.78%; CI: 14.23–19.69%), Europe (12.30%; CI: 7.07–20.53%), Asia Pacific (11.0%; CI: 4.65–23.85%), Middle East (6.0%; CI: 3.44–10.27%), and Latin America (5.82%; CI: 3.25–10.20).

Among the resistant organisms reported, MRSA had the highest pooled prevalence (6.23%; CI: 3.83–9.97%), followed by ESBL (6.19%; CI: 3.32–11.26%), and lastly VRE with the lowest reported prevalence (1.91%; CI: 0.41–8.46%). North America had the highest pooled prevalence of ESBL (10.18%; CI: 2.34–34.90%). Europe had the highest pooled prevalence of MRSA and VRE (6.63%; CI: 3.70–11.61%) and (10.53%; CI: 2.65–33.74%), respectively.

Outcomes in SBP Cirrhosis

Incidence of outcomes after SBP infection are summarized in Table 2. The prevalence of SBP and its associated outcomes are illustrated in Figure 5. Overall mortality was 30.61% (CI: 23.30–39.06%), in-hospital mortality (23.38%; CI: 15.18–34.22%), 30-day mortality (25.64%; CI: 22.46–29.11%), 90-day mortality (37.64%; CI: 31.62–44.08%). Acute kidney injury (AKI) had a prevalence of 49.38% (CI: 30.76–68.18%), while SBP recurrence had a prevalence of 15.74% (CI: 12.46–19.67%). Patients with CNNA were observed to have a significantly lower risk of mortality compared to CPNA patients (OR = 0.96; CI: 0.94–0.99; p < 0.01). However, no significant difference in mortality was observed between BA and CPNA patients (OR: 1.04, CI: 0.987–1.094).

Figure 5. Summary of the prevalence of SBP and its associated outcomes. Image created with Biorender.com.

Subgroup Analysis on Income Levels

A subgroup analysis of clinical outcomes was conducted according to income level as per World Bank definitions (Table 4). The rate of SBP is significantly higher in patients from middle-income countries (20.27%; CI: 14.89–26.97%) compared to patients from high-income countries (15.44%; CI: 11.29–20.75%) with a relative risk of 1.31 (CI: 1.25–1.37, p < 0.01). Middle-income countries were observed to have a higher risk of AKI as a complication (RR = 1.56; CI: 1.47–1.66; p < 0.01) than high-income countries. Other outcomes including antibiotic resistance, 30-day mortality and 90-day mortality were observed to be higher in middle-income countries although without significance.

Discussion

SBP is a common yet debilitating complication of decompensated liver cirrhosis, inflicting a significant global burden (5, 6). This meta-analysis demonstrates the worldwide prevalence, risk factors and outcomes of SBP with notable variation based on different geographical locations and income groups. We found the global pooled prevalence of SBP to be 17.12%, with large variability in prevalence of SBP among geographic regions. The reported prevalence of SBP was four times higher in Africa compared to North America (44.54%; CI 18.15−0.7442 vs. 10.81%; CI 5.32–20.73%, respectively).

Despite aggressive case identification and treatment, SBP remains a significant burden to the healthcare system and was found to have a high mortality rate of 30.61% in our study, comparable to that of variceal bleeding (121). Although this has improved significantly from more than 90% when Harold Conn first described SBP in the 1970s (1), patients with concurrent risk factors are still at a higher risk of mortality. In a large-scale study by Niu et al. which examined 88,167 SBP hospitalizations with 29,963 deaths, it was found that older age, female gender, hepatic encephalopathy, coagulopathy, variceal hemorrhage, sepsis, pneumonia, and acute kidney injury were associated with increased in-patient mortality (122).

Additionally, AKI was found to be a significant outcome of SBP with a prevalence of 49.38%. Renal dysfunction is a common complication of SBP, and a study by Devani et al. demonstrated that there has been an ~2-fold rise of AKI among patients hospitalized with SBP over the past 10 years (98). AKI is also the most important independent predictor of mortality (123) and in a study by Karagozian et al. it was reported that patients with SBP who develop renal failure are more likely to require dialysis and have higher mortality (124).

Interestingly, pooled analysis found that patients with CNNA had significantly lower mortality compared to CPNA patients (OR = 0.96; CI: 0.94–0.99; p < 0.01). This is corroborated by previous cohort studies reporting increased mortality in CPNA compared to CNNA patients, attributing this to increased bacterial load in the former (1, 125). Decreased serum and ascitic complement levels, low ascitic fluid protein levels, and reduced activity of the reticulo-endothelial system have been suggested as potential mechanisms for increased severity of ascitic fluid infection in CPNA (126). This could be further confounded by favorable hepatic function in CNNA vs. CPNA patients, as demonstrated by better Child-Pugh scores in the CNNA group reported in previous cohort studies (94, 127). A greater degree of portal hypertension consequent of poorer hepatic function may result in more bacterial translocation, contributing to increased severity of infection, and consequently mortality (94).

This study also reports the overall prevalence of antibiotic resistance in SBP to be 11.51%, with MRSA having the highest prevalence of 6.23%, followed by ESBL (6.19%) and VRE (1.91%). The prevalence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria has been rising due to a global misuse of antibiotics (128), along with the increased frequency of hospitalization and need for invasive procedures in patients with cirrhosis (129). Additionally, rates of resistance varied by continent, which may be a product of varying national antibiotic regimens and policies (130). Proper understanding of resistance rates is essential in determining the appropriate choice of empirical antibiotics, with additional considerations based on the source of infection (61). For community-acquired SBP, the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) recommends that a third-generation cephalosporin be used as the first-line antibiotic treatment in countries with low rates of bacterial resistance, while piperacillin/tazobactam or carbapenem should be reserved for community-acquired cases in countries with high rates of resistance. Due to the increased prevalence of multi-drug resistance in healthcare-associated SBP, the EASL guidelines recommend piperacillin/tazobactam for healthcare-related cases in areas with low prevalence of multi-drug resistance. In regions where multi-drug resistant bacteria are more common, carbapenem in combination with linezolid or glycopeptides can be considered (20).

Interestingly, in regions with lower overall prevalence of SBP such as Europe and North America, there were higher rates of antibiotic resistance (Figure 4). This could possibly be attributed to strong adherence to guideline recommendations for prophylaxis in high-risk patients. Randomized control trials have demonstrated that norfloxacin prophylaxis in patients with increased Child-Pugh scores, impaired renal function, or low ascitic protein count was associated with significantly decreased SBP occurrence and increased short-term survival (10). However, it is possible that inappropriate continuation of prophylaxis in patients with improved clinical condition could give rise to multi-drug resistant organisms. In line with EASL guidelines, adequate risk profiling should be conducted to determine the necessity of SBP prophylaxis in order to ensure proper antibiotic stewardship (20).

Finally, socioeconomic status was found to be a significant factor in SBP development, with significantly higher SBP prevalence in patients from middle-income countries compared to patients from higher-income countries. Patients from middle-income countries also had poorer outcomes in terms of 30-day and 90-day mortality, and occurrence of AKI. However, only the relative risk of AKI reached statistical significance (Table 4). Lower-income levels have previously been associated with more advanced disease due to ill-equipped healthcare facilities and poor health literacy (131). Additionally, poorer nutrition in patients from lower-income countries including vitamin D deficiency (132, 133), and increased time to initiation of antibiotics could have further affected outcomes (131). Antimicrobial resistance was also more prevalent in the middle-income group, although it did not reach statistical significance. A multi-country survey by the World Health Organization (WHO) found antibiotic use to be higher in lower-income countries (134), possibly influencing the higher resistance rates.

Strengths and Limitations

To our best knowledge, this is the first meta-analysis of global prevalence, associative risk factors and outcomes of SBP in patients with liver cirrhosis. Its strengths include the large sample size and rigor in analysis. It is also the first to report the possible impact of socioeconomic status on SBP. A major limitation of this analysis lies in the heterogeneity of the included studies, based on the I2 statistic However, larger sample sizes are often associated with increased I2 in simulation studies (135, 136). Thus, a meta-analysis conducted for prevalence often has a large I2-value (>90%) due to the larger sample sizes involved (137, 138). Current methods of heterogeneity measures are inaccurate in prevalence based meta-analysis (139). Additionally, there is possible underrepresentation of cohorts from lower-income countries, and regions including Africa and Latin America due to publication bias, hence confounding the actual impact of SBP in such communities. The underrepresentation may also be attributed to the exclusion of non-English studies. However, the absence of professional language translators prevents the inclusion of non-English studies and may cause misinterpretation (140). Current translation software (google scholar) has been found to be ill-equipped for systematic review (141).

Conclusion

This systematic review is the first to provide an analysis of SBP rates on a global level. It also draws an unprecedented link between socioeconomic status and the prevalence of SBP. The discoveries made in this review may assist in the generation of policies to tackle SBP in liver cirrhosis on a community or even global health level. The investigation of antibiotic-resistant microorganism profile according to region highlights the importance of avoiding antibiotic misuse. Thus, this review may help equip physicians with greater awareness of their local antibiotic-resistant microorganism profile and appropriate treatment.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Author Contributions

MM, CN, and ET: conceptualization. PT, JX, DT, CN, YL, WL, VT, RH, and MY: data curation. PT, JX, DT, and CN: formal analysis. ET, GK, GL, and MM: supervision. PT, JX, DT, CN, YL, WL, VT, RH, MY, and LL: validation. PT, JX, DT, CN, YL, WL, ET, and MM: writing—original draft. PT, JX, DT, CN, YL, WL, VT, RH, MY, LL, ET, GK, GL, and MM: writing—review and editing. All authors read and gave final approval of the version to be submitted.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmed.2021.693652/full#supplementary-material

Abbreviations

AKI, Acute kidney injury; AASLD, American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases; BA, Bacterascites; CPNA, Culture-positive neutrocytic ascites; CNNA, culture-negative neutrocytic ascites; EASL, European Association for the Study of the Liver; ESBL, Extended-spectrum beta-lactamase; HCC, Hepatocellular carcinoma; MOOSE, Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology; MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; NASH, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis; PMN, polymorphonuclear; SBP, Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis; VRE, vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus; WHO, World Health Organisation.

References

1. Koulaouzidis A, Bhat S, Karagiannidis A, Tan WC, Linaker BD. Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Postgrad Med J. (2007) 83:379–83. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2006.056168

2. Runyon BA. Introduction to the revised American association for the study of liver diseases practice guideline management of adult patients with ascites due to cirrhosis 2012. Hepatology. (2013) 57:1651–3. doi: 10.1002/hep.26359

3. Marciano S, Diaz JM, Dirchwolf M, Gadano A. Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in patients with cirrhosis: incidence, outcomes, and treatment strategies. Hepat Med. (2019) 11:13–22. doi: 10.2147/HMER.S164250

4. Duah A, Nkrumah KN. Prevalence and predictors for spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in cirrhotic patients with ascites admitted at medical block in Korle-Bu teaching hospital, Ghana. Pan Afr Med J. (2019) 33:35. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2019.33.35.18029

5. Lata J, Fejfar T, Krechler T, Musil T, Husova L, Senkyrik M, et al. Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in the Czech republic: prevalence and aetiology. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. (2003) 15:739–43. doi: 10.1097/01.meg.0000059160.46867.62

6. Oladimeji AA, Temi AP, Adekunle AE, Taiwo RH, Ayokunle DS. Prevalence of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in liver cirrhosis with ascites. Pan Afr Med J. (2013) 15:128. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2013.15.128.2702

7. Al-Ghamdi H, Al-Harbi N, Mokhtar H, Daffallah M, Memon Y, Aljumah AA, et al. Changes in the patterns and microbiology of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis : analysis of 200 cirrhotic patients. Acta Gastroenterol Belg. (2019) 82:261–6.

8. MacIntosh T. Emergency management of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis - a clinical review. Cureus. (2018) 10:e2253. doi: 10.7759/cureus.2253

9. Ather MM, Arif MM, Qadir M, Khan HR, Khaliq SA, Rasheeq T. Frequency of asymptomatic spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in outdoor patients with liver cirrhosis. Med Forum Month. (2019) 30:2–5.

10. Díaz-Hernández HA, Vázquez-Anaya G, Miranda-Zazueta G, Castro-Narro GE. The impact of different infectious complications on mortality of hospitalized patients with liver cirrhosis. Ann Hepatol. (2020) 19:427–36. doi: 10.1016/j.aohep.2020.02.005

11. Bernardi M. Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis: from pathophysiology to prevention. Intern Emerg Med. (2010) 5(Suppl.1):S37–44. doi: 10.1007/s11739-010-0446-x

12. Ameer MA, Foris LA, Mandiga P, Haseeb M. Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing (2020).

13. Alvarez-Silva C, Schierwagen R, Pohlmann A, Magdaleno F, Uschner FE, Ryan P, et al. Compartmentalization of immune response and microbial translocation in decompensated cirrhosis. Front Immunol. (2019) 10:69. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00069

14. Bartoletti M, Giannella M, Caraceni P, Domenicali M, Ambretti S, Tedeschi S, et al. Epidemiology and outcomes of bloodstream infection in patients with cirrhosis. J Hepatol. (2014) 61:51–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.03.021

15. Holguín Cardona A, Hurtado Guerra JJ, Restrepo Gutiérrez JC. Una mirada actual a la peritonitis bacteriana espontánea. Rev Colomb Gastroenterol. (2015) 30:315–24. doi: 10.22516/25007440.56

16. Alaniz C, Regal RE. Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis: a review of treatment options. PT. (2009) 34:204–10.

17. Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, Olkin I, Williamson GD, Rennie D, et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA. (2000) 283:2008–12. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.15.2008

18. Venditti M, Falcone M, Corrao S, Licata G, Serra P. Outcomes of patients hospitalized with community-acquired, health care-associated, and hospital-acquired pneumonia. Ann Intern Med. (2009) 150:19–26. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-1-200901060-00005

19. Chon YE, Kim SU, Lee CK, Park JY, Kim DY, Han KH, et al. Community-acquired vs. nosocomial spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in patients with liver cirrhosis. Hepatogastroenterology. (2014) 61:2283–90.

20. European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL clinical practice guidelines for the management of patients with decompensated cirrhosis. J Hepatol. (2018) 69:406–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.03.024

21. Schwarzer G, Chemaitelly H, Abu-Raddad LJ, Rücker G. Seriously misleading results using inverse of freeman-tukey double arcsine transformation in meta-analysis of single proportions. Res Synth Methods. (2019) 10:476–83. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.1348

22. Fletcher J. What is heterogeneity and is it important? BMJ. (2007) 334:94–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39057.406644.68

23. Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. (2003) 327:557–60. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557

24. Hunter JP, Saratzis A, Sutton AJ, Boucher RH, Sayers RD, Bown MJ. In meta-analyses of proportion studies, funnel plots were found to be an inaccurate method of assessing publication bias. J Clin Epidemiol. (2014) 67:897–903. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.03.003

25. Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ, Elbers RG, Blencowe NS, Boutron I, et al. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. (2019) 366:l4898. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l4898

26. Tan DJH, Wong C, Ng CH, Poh CW, Jain SR, Huang DQ, et al. A meta-analysis on the rate of hepatocellular carcinoma recurrence after liver transplant and associations to etiology, alpha-fetoprotein, income and ethnicity. J Clin Med. (2021) 10:238. doi: 10.3390/jcm10020238

27. Katz D, Baptista J, Azen SP, Pike MC. Obtaining confidence intervals for the risk ratio in cohort studies. Biometrics. (1978) 34:469–74. doi: 10.2307/2530610

28. Neo VSQ, Jain SR, Yeo JW, Ng CH, Gan TRX, Tan E, et al. Controversies of colonic stenting in obstructive left colorectal cancer: a critical analysis with meta-analysis and meta-regression. Int J Colorectal Dis. (2021) 36:689–700. doi: 10.1007/s00384-021-03834-9

29. Xiao J, Lim LKE, Ng CH, Tan DJH, Lim WH, Ho CSH, et al. Is fatty liver associated with depression? A meta-analysis and systematic review on the prevalence, risk factors, and Outcomes of depression and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Front Med. (2021) 8:691696. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.691696

30. Hoy D, Brooks P, Woolf A, Blyth F, March L, Bain C, et al. Assessing risk of bias in prevalence studies: modification of an existing tool and evidence of interrater agreement. J Clin Epidemiol. (2012) 65:934–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.11.014

31. Bejar-Serrano S, Del Pozo P, Fernandez-de la Varga M, Benlloch S. Multidrug-resistant bacterial infections in patients with liver cirrhosis in a tertiary referral hospital. Gastroenterol Hepatol. (2019) 42:228–38. doi: 10.1016/j.gastre.2019.03.010

32. Bystrianska N, Skladany L, Adamcova-Selcanova S, Vnencakova J, Jancekova D, Koller T. Infection in patients hospitalised with advanced chronic liver disease (cirrhosis) - single-centre experience. Gastroenterol Hepatol. (2020) 74:111–5. doi: 10.14735/amgh2020111

33. Melcarne L, Sopeña J, Martínez-Cerezo FJ, Vergara M, Miquel M, Sánchez-Delgado J, et al. Prognostic factors of liver cirrhosis mortality after a first episode of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. A multicenter study. Rev Espan Enfermed Dig. (2018) 110:94–101. doi: 10.17235/reed.2017.4517/2016

34. Salerno F, Borzio M, Pedicino C, Simonetti R, Rossini A, Boccia S, et al. The impact of infection by multidrug-resistant agents in patients with cirrhosis. A multicenter prospective study. Liver Int. (2017) 37:71–9. doi: 10.1111/liv.13195

35. Oliveira AM, Branco JC, Barosa R, Rodrigues JA, Ramos L, Martins A, et al. Clinical and microbiological characteristics associated with mortality in spontaneous bacterial peritonitis: a multicenter cohort study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. (2016) 28:1216–22. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000000700

36. Lim KHJ, Potts JR, Chetwood J, Goubet S, Verma S. Long-term outcomes after hospitalization with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. J Dig Dis. (2015) 16:228–40. doi: 10.1111/1751-2980.12228

37. Preveden T. Bacterial infections in patients with liver cirrhosis. Med Pregl. (2015) 68:187–91. doi: 10.2298/MPNS1506187P

38. Vergara M, Clèries M, Vela E, Bustins M, Miquel M, Campo R. Hospital mortality over time in patients with specific complications of cirrhosis. Liver Int. (2013) 33:828–33. doi: 10.1111/liv.12137

39. Wlazlo N, van Greevenbroek MM, Curvers J, Schoon E J, Friederich P, Twisk JWR, et al. Diabetes mellitus at the time of diagnosis of cirrhosis is associated with higher incidence of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, but not with increased mortality. Clin Sci. (2013) 125:341–8. doi: 10.1042/CS20120596

40. Novovic S, Semb S, Olsen H, Moser C, Knudsen JD, Homann C. First-line treatment with cephalosporins in spontaneous bacterial peritonitis provides poor antibiotic coverage. Scand J Gastroenterol. (2012) 47:212–6. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2011.645502

41. Wiegand J, Kühne M, Pradat P, Mössner J, Trepo C, Tillmann HL. Different patterns of decompensation in patients with alcoholic vs. non-alcoholic liver cirrhosis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. (2012) 35:1443–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2012.05108.x

42. Kasztelan-Szczerbinska B, Slomka M, Celinski K, Serwacki M, Szczerbinski M, Cichoz-Lach H. Prevalence of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in asymptomatic inpatients with decompensated liver cirrhosis - a pilot study. Adv Med Sci. (2011) 56:13–7. doi: 10.2478/v10039-011-0010-6

43. Gunjaca I, Francetic I. Prevalence and clinical outcome of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in hospitalized patients with liver cirrhosis: a prospective observational study in central part of croatia. Acta Clin. (2010) 49:11–8.

44. Diaz-Sanchez A, Nunez-Martinez O, Gonzalez-Asanza C, et al. Portal hypertensive colopathy is associated with portal hypertension severity in cirrhotic patients. World J Gastroenterol. (2009) 15:4781–7. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.4781

45. Piroth L, Pechinot A, Minello A, Jaulhac B, Patry I, Hadou T, et al. Bacterial epidemiology and antimicrobial resistance in ascitic fluid: a 2-year retrospective study. Scand J Infect Dis. (2009) 41:847–51. doi: 10.3109/00365540903244535

46. Castellote J, Girbau A, Maisterra S, Charhi N, Ballester R, Xiol X. Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis and bacterascites prevalence in asymptomatic cirrhotic outpatients undergoing large-volume paracentesis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. (2008) 23:256–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2007.05081.x

47. Fasolato S, Angeli P, Dallagnese L, Maresio G, Zola E, Mazza E, et al. Renal failure and bacterial infections in patients with cirrhosis: epidemiology and clinical features. Hepatology. (2007) 45:223–9. doi: 10.1002/hep.21443

48. Nousbaum JB, Cadranel JF, Nahon P, Khac EN, Moreau R, Thévenot T, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of the Multistix 8 SG reagent strip in diagnosis of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Hepatology. (2007) 45:1275–81. doi: 10.1002/hep.21588

49. Cholongitas E, Papatheodoridis GV, Manesis EK, Burroughs AK, Archimandritis AJ. Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in cirrhotic patients: is prophylactic propranolol therapy beneficial? J Gastroenterol Hepatol. (2006) 21:581–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2005.03982.x

50. Abraldes JG, Tarantino I, Turnes J, Garcia-Pagan JC, Rodés J, Bosch J. Hemodynamic response to pharmacological treatment of portal hypertension and long-term prognosis of cirrhosis. Hepatology. (2003) 37:902–8. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50133

51. Fernandez J, Navasa M, Gomez J, Colmenero J, Vila J, Arroyo V, et al. Bacterial infections in cirrhosis: epidemiological changes with invasive procedures and norfloxacin prophylaxis. Hepatology. (2002) 35:140–8. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.30082

52. Bauer TM, Steinbruckner B, Brinkmann FE, Ditzen AK, Schwacha H, Aponte JJ, et al. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in patients with cirrhosis: prevalence and relation with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Am J Gastroenterol. (2001) 96:2962–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.04668.x

53. Campillo B, Dupeyron C, Richardet JP. Epidemiology of hospital-acquired infections in cirrhotic patients: effect of carriage of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and influence of previous antibiotic therapy and norfloxacin prophylaxis. Epidemiol Infect. (2001) 127:443–50. doi: 10.1017/S0950268801006288

54. Dupeyron C, Campillo SB, Mangeney N, Richardet JP, Leluan G. Carriage of Staphylococcus aureus and of gram-negative bacilli resistant to third-generation cephalosporins in cirrhotic patients: a prospective assessment of hospital-acquired infections. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. (2001) 22:427–32. doi: 10.1086/501929

55. Kraja B, Sina M, Mone I, Pupuleku F, Babameto A, Prifti S, et al. Predictive value of the model of end-stage liver disease in cirrhotic patients with and without spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Gastroenterol Res Pract. (2012) 2012:539059. doi: 10.1155/2012/539059

56. Lutz P, Goeser F, Kaczmarek DJ, Schlabe S, Nischalke HD, Nattermann J, et al. Relative ascites polymorphonuclear cell count indicates bacterascites and risk of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Dig Dis Sci. (2017) 62:2558–68. doi: 10.1007/s10620-017-4637-4

57. Lutz P, Berger C, Langhans B, Grünhage F, Appenrodt B, Nattermann J, et al. A farnesoid X receptor polymorphism predisposes to spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Dig Liver Dis. (2014) 46:1047–50. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2014.07.008

58. Mayr U, Lukas M, Elnegouly M, Vogt C, Bauer U, Ulrich J, et al. Ascitic interleukin 6 is associated with poor outcome and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis: a validation in critically ill patients with decompensated cirrhosis. J Clin Med. (2020) 9:1–15. doi: 10.3390/jcm9092865

59. Piotrowski D, Saczewska-Piotrowska A, Jaroszewicz J, Boron-Kaczmarska A. Lymphocyte-To-Monocyte ratio as the best simple predictor of bacterial infection in patients with liver cirrhosis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17:1727. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17051727

60. Schwabl P, Bucsics T, Soucek K, Mandorfer M, Bota S, Blacky A, et al. Risk factors for development of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis and subsequent mortality in cirrhotic patients with ascites. Liver Int. (2015) 35:2121–8. doi: 10.1111/liv.12795

61. Fernández J, Acevedo J, Castro M, Garcia O, Rodríguez de Lope C, Roca D, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of infections by multiresistant bacteria in cirrhosis: a prospective study. Hepatology. (2012) 55:1551–61. doi: 10.1002/hep.25532

62. Wong YJ, Kalki RC, Lin KW, Lin K W, Kumar R, Tan J, et al. Short- and long-term predictors of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in singapore. Singapore Med J. (2020) 61:419–25. doi: 10.11622/smedj.2019085

63. Li B, Gao Y, Wang X, Qian Z, Meng Z, Huang Y, et al. Clinical features and outcomes of bacterascites in cirrhotic patients: a retrospective, multicentre study. Liver Int. (2020) 40:1447–56. doi: 10.1111/liv.14418

64. Chen PC, Chen BH, Huang CH, Jeng W-J, Hsieh Y-C, Teng W, et al. Integrated model for end-stage liver disease maybe superior to some other model for end-stage liver disease-based systems in addition to child-turcotte-pugh and albumin-bilirubin scores in patients with hepatitis B virus-related liver cirrhosis and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. (2019) 31:1256–63. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000001481

65. Ding X, Yu Y, Chen M, Wang C, Kang Y, Lou J. Causative agents and outcome of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in cirrhotic patients: community-acquired versus nosocomial infections. BMC Infect Dis. (2019) 19:463. doi: 10.1186/s12879-019-4102-4

66. Ning NZ, Li T, Zhang JL, Qu F, Huang J, et al. Clinical and bacteriological features and prognosis of ascitic fluid infection in Chinese patients with cirrhosis. BMC Infect Dis. (2018) 18:253. doi: 10.1186/s12879-018-3101-1

67. Hung TH, Tsai CC, Hsieh YH, Tsai CC, Tseng CW, Tseng KC. The effect of the first spontaneous bacterial peritonitis event on the mortality of cirrhotic patients with ascites: a nationwide population-based study in Taiwan. Gut Liver. (2016) 10:803–7. doi: 10.5009/gnl13468

68. Hung TH, Tsai CC, Hsieh YH, Tsai CC. The long-term mortality of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in cirrhotic patients: a 3-year nationwide cohort study. Turkish J Gastroenterol. (2015) 26:159–62. doi: 10.5152/tjg.2015.4829

69. Hung TH, Lay CJ, Chang CM, Tsai JJ, Tsai CC, Tsai CC. The effect of infections on the mortality of cirrhotic patients with hepatic encephalopathy. Epidemiol Infect. (2013) 141:2671–8. doi: 10.1017/S0950268813000186

70. Shizuma T, Fukuyama N. Investigation into bacteremia and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in patients with liver cirrhosis in Japan. Turkish J Gastroenterol. (2012) 23:122–6. doi: 10.4318/tjg.2012.0321

71. Kim SU, Kim DY, Lee CK, Park JY, Kim SH, Kim HM, et al. Ascitic fluid infection in patients with hepatitis B virus-related liver cirrhosis: culture-negative neutrocytic ascites versus spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. (2010) 25:122–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2009.05970.x

72. Heo J, Yeon SS, Hyung JY, Hahn T, Park SH, Ahn SH, et al. Clinical features and prognosis of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in Korean patients with liver cirrhosis: a multicenter retrospective study. Gut Liver. (2009) 3:197–204. doi: 10.5009/gnl.2009.3.3.197

73. Kim SU, Han KH, Nam CM, Park JY, Kim DY, Chon CY, et al. Natural history of hepatitis B virus-related cirrhotic patients hospitalized to control ascites. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. (2008) 23:1722–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2008.05510.x

74. Gayatri AA, Suryadharma IG, Purwadi N, Wibawa ID. The relationship between a model of end stage liver disease score (MELD score) and the occurrence of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in liver cirrhotic patients. Acta Med. (2007) 39:75–8.

75. Wang Y, Xiao SS, He JF, Liu R, Yu R. Risk factors of decompensated cirrhosis complicated with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. World Chin J Digestol. (2006) 14:2034–6. doi: 10.11569/wcjd.v14.i20.2034

76. Kwon SY, Kim SS, Kwon OS, Kwon KA, Chung MG, Park DY, et al. Prognostic significance of glycaemic control in patients with HBV and HCV-related cirrhosis and diabetes mellitus. Diabet Med. (2005) 22:1530–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2005.01687.x

77. Kim YS, Um SH, Ryu HS, Lee JB, Lee JW, Park DK, et al. The prognosis of liver cirrhosis in recent years in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. (2003) 18:833–41. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2003.18.6.833

78. Chang CS, Yang SS, Kao CH, Yeh HZ, Chen GH. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth versus antimicrobial capacity in patients with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Scand J Gastroenterol. (2001) 36:92–6. doi: 10.1080/00365520150218110

79. Cho Y, Park SY, Lee JH, Lee DH, Lee M, Yoo JJ, et al. High-sensitivity C-reactive protein level is an independent predictor of poor prognosis in cirrhotic patients with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. J Clin Gastroenterol. (2014) 48:444–9. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3182a6cdef

80. Lee SS, Min HJ, Choi JY, Cho HC, Kim JJ, Lee JM, et al. Usefulness of ascitic fluid lactoferrin levels in patients with liver cirrhosis. BMC Gastroenterol. (2016) 16:132. doi: 10.1186/s12876-016-0546-9

81. Tsung PC, Ryu SH, Cha IH, Cho HW, Kim JN, Kim YS, et al. Predictive factors that influence the survival rates in liver cirrhosis patients with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Clin Mol Hepatol. (2013) 19:131–9. doi: 10.3350/cmh.2013.19.2.131

82. Xiong J, Zhang M, Guo X, Pu L, Xiong H, Xiang P, et al. Acute kidney injury in critically ill cirrhotic patients with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis: a comparison of KDIGO and ICA criteria. Arch Med Sci. (2020) 16:569–76. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2019.85148

83. Sanglodkar U, Jain M, Venkataraman J. Predictors of immediate and short-term mortality in spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Indian J Gastroenterol. (2020) 39:331–7. doi: 10.1007/s12664-020-01040-z

84. Jain M, Varghese J, Kedarishetty CK, Srinivasan V, Venkataraman J. Incidence and risk factors for mortality in patients with cirrhosis awaiting liver transplantation. Indian J Transplant. (2019) 13:210–5. doi: 10.4103/ijot.ijot_27_19

85. Maitra T, Das SP, Barman P, Deka J. Spectrum of complications of chronic liver disease in gauhati medical college and hospital: a hospital based study. J Clin Diagnost Res. (2019) 13:OC07–12. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2019/36606.12938

86. Sarwar S, Tarique S, Waris U, Khan AA. Cephalosporin resistance in community acquired spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Pak J Med Sci. (2019) 35:4–9. doi: 10.12669/pjms.35.1.17

87. Rout G, Jadaun SS, Ranjan G, Kedia S, Gunjan D, et al. Prevalence, predictors and impact of bacterial infection in acute on chronic liver failure patients. Dig Liver Dis. (2018) 50:1225–31. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2018.05.013

88. Bilal MH, Tahir M, Khan NA. Frequency of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in liver cirrhosis patients having hepatic encephalopathy. Pak J Med Health Sci. (2015) 9:70–2.

89. Paul K, Kaur J, Kazal HL. To study the incidence, predictive factors and clinical outcome of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in patients of cirrhosis with ascites. J Clin Diagnost Res. (2015) 9:9–12. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2015/14855.6191

90. Baijal R, Amarapurkar D, Praveen Kumar HR, Kulkarni S, Shan N, Doshi S, et al. A multicenter prospective study of infections related morbidity and mortality in cirrhosis of liver. Indian J Gastroenterol. (2014) 33:336–42. doi: 10.1007/s12664-014-0461-3

91. Benjamin J, Singla V, Arora I, Sood S, Joshi YK. Intestinal permeability and complications in liver cirrhosis: a prospective cohort study. Hepatol Res. (2013) 43:200–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1872-034X.2012.01054.x

92. Bhat G, Vandana KE, Bhatia S, Suvarna D, Pai CG. Spontaneous ascitic fluid infection in liver cirrhosis: bacteriological profile and response to antibiotic therapy. Indian J Gastroenterol. (2013) 32:297–301. doi: 10.1007/s12664-013-0329-y

93. Haider I, Ahmad I, Rashid A, Bashir H. Causative organisms and their drug sensitivity pattern in ascitic fluid of cirrhotic patients with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. J Postgrad Med Inst. (2008) 22:333–339.

94. Kamani L, Mumtaz K, Ahmed US, Ali AW, Jafri W. Outcomes in culture positive and culture negative ascitic fluid infection in patients with viral cirrhosis: cohort study. BMC Gastroenterol. (2008) 8:59. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-8-59

95. Syed VA, Ansari JA, Karki P, Regmi M, Khanal B. Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP) in cirrhotic ascites: a prospective study in a tertiary care hospital, Nepal. Kathmandu Univ. (2007) 5:48–59.

96. Jain M, Sanglodkar U, Venkataraman J. Risk factors predicting nosocomial, healthcare-associated and community-acquired infection in spontaneous bacterial peritonitis and survival outcome. Clin Exp Hepatol. (2019) 5:133–9. doi: 10.5114/ceh.2019.85073

97. Santoiemma PP, Dakwar O, Angarone MP. A retrospective analysis of cases of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in cirrhosis patients. PLoS ONE. (2020) 15:e0239470. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0239470

98. Devani K, Charilaou P, Jaiswal P, Patil N, Radadiya D, Patel P, et al. Trends in hospitalization, acute kidney injury, and mortality in patients with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. J Clin Gastroenterol. (2019) 53:e68–74. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000000973

99. Khan R, Ravi S, Chirapongsathorn S, Jennings W, Salameh H, Russ K, et al. Model for end-stage liver disease score predicts development of first episode of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in patients with cirrhosis. Mayo Clin Proc. (2019) 94:1799–806. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2019.02.027

100. Chaulk J, Carbonneau M, Qamar H, Keough A, Chang HJ, Ma M, et al. Third-generation cephalosporin-resistant spontaneous bacterial peritonitis: a single-centre experience and summary of existing studies. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. (2014) 28:83–8. doi: 10.1155/2014/429536

101. Singal AK, Salameh H, Kamath PS. Prevalence and in-hospital mortality trends of infections among patients with cirrhosis: a nationwide study of hospitalised patients in the United States. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. (2014) 40:105–12. doi: 10.1111/apt.12797

102. Bajaj JS, O'Leary JG, Reddy KR, Wong F, Olson J C, Subramanian RM, et al. Second infections independently increase mortality in hospitalized patients with cirrhosis: the North American consortium for the study of end-stage liver disease (NACSELD) experience. Hepatology. (2012) 56:2328–35. doi: 10.1002/hep.25947

103. Evans LT, Kim WR, Poterucha JJ, Kamath PS. Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in asymptomatic outpatients with cirrhotic ascites. Hepatology. (2003) 37:897–901. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50119

104. Liangpunsakul S, Ulmer BJ, Chalasani N. Predictors and implications of severe hypersplenism in patients with cirrhosis. Am J Med Sci. (2003) 326:111–6. doi: 10.1097/00000441-200309000-00001

105. Hampel H, Bynum GD, Zamora E, El-Serag HB. Risk factors for the development of renal dysfunction in hospitalized patients with cirrhosis. Am J Gastroenterol. (2001) 96:2206–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03958.x

106. Cullaro G, Kim G, Pereira MR, Brown RS, Verna EC. Ascites neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin identifies spontaneous bacterial peritonitis and predicts mortality in hospitalized patients with cirrhosis. Dig Dis Sci. (2017) 62:3487–94. doi: 10.1007/s10620-017-4804-7

107. Liu TL, Trogdon J, Weinberger M, Fried B, Barritt AST. Diabetes is associated with clinical decompensation events in patients with cirrhosis. Dig Dis Sci. (2016) 61:3335–45. doi: 10.1007/s10620-016-4261-8

108. Sofjan AK, Musgrove RJ, Beyda ND, Russo HP, Lasco TM, Yau R, et al. Prevalence and predictors of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis due to ceftriaxone-resistant organisms at a large tertiary centre in the USA. J Glob Antimicrob Resist. (2018) 15:41–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jgar.2018.05.015

109. Ardolino E, Wang SS, Patwardhan VR. Evidence of significant ceftriaxone and quinolone resistance in cirrhotics with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Dig Dis Sci. (2019) 64:2359–67. doi: 10.1007/s10620-019-05519-4

110. Makhlouf NA, Ghaliony MA, El-Dakhli SA, Abu Elfatth AM, Mahmoud AA. Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis among cirrhotic patients in upper Egypt: clinical and bacterial profiles. J Gastroenterol Hepatol Res. (2019) 8:3014–9. doi: 10.17554/j.issn.2224-3992.2019.08.851

111. Iliaz R, Ozpolat T, Baran B, Demir K, Kaymakoglu S, Besisik F, et al. Predicting mortality in patients with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis using routine inflammatory and biochemical markers. Euro J Gastroenterol Hepatol. (2018) 30:786–91. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000001111

112. Mazloom SS, Khoramian MK, Mohsenian L. Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in afebrile cirrhotic patients; report from a referral transplantation center. Bull Emerge Trauma. (2018) 6:363–6. doi: 10.29252/beat-060415

113. Jmaa A, Ksiaa M, Ben Slama A, Kahlon A, Jmaa R, Harrabi I, et al. The natural history of hepatitis B virus cirrhosis after the first hepatic decompensation in tunisia. La Tunisie Méd. (2012) 90:172–6.

114. Abdel-Razik A, Mousa N, Abdel-Aziz M, Elsherbiny W, Zakaria S, Shabana W, et al. Mansoura simple scoring system for prediction of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis: lesson learnt. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. (2019) 31:1017–24. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000001364

115. Ensaroglu F, Korkmaz M, Geckil AU, Ocal S, Koç B, Yildiz O, et al. Factors affecting mortality and morbidity of patients with cirrhosis hospitalized for spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Exp Clin Transplant. (2015) 13 (Suppl. 3):131–6. doi: 10.6002/ect.tdtd2015.P71

116. Almeida PRL, Leao GS, Goncalves CDG, Picon RV, Tovo CV. Impact of microbiological changes on spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in three different periods over 17 years. Arq Gastroenterol. (2018) 55:23–7. doi: 10.1590/s0004-2803.201800000-08

117. Marciano S, Dirchwolf M, Bermudez CS, Sobenko N, Haddad L, Bert FG, et al. Spontaneous bacteremia and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis share similar prognosis in patients with cirrhosis: a cohort study. Hepatol Int. (2018) 12:181–90. doi: 10.1007/s12072-017-9837-7

118. Thiele GB, da Silva OM, Fayad L, Lazzarotto C, Ferreira MdA, Marconcini ML, et al. Clinical and laboratorial features of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in southern Brazil. São Paulo Medical Journal. (2014) 132:205–10. doi: 10.1590/1516-3180.2014.1324698

119. Perdomo Coral G, Alves de Mattos A. Renal impairment after spontaneous bacterial peritonitis: incidence and prognosis. Can J Gastroenterol. (2003) 17:187–90. doi: 10.1155/2003/370257

120. Rosa H, Silverio AO, Perini RF, Arruda CB. Bacterial infection in cirrhotic patients and its relationship with alcohol. Am J Gastroenterol. (2000) 95:1290–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.02026.x

122. Niu B, Kim B, Limketkai BN, Sun J, Li Z, Woreta T, et al. Mortality from spontaneous bacterial peritonitis among hospitalized patients in the USA. Dig Dis Sci. (2018) 63:1327–33. doi: 10.1007/s10620-018-4990-y

123. Tandon P, Garcia-Tsao G. Renal dysfunction is the most important independent predictor of mortality in cirrhotic patients with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. (2011) 9:260–5. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2010.11.038

124. Karagozian R, Rutherford AE, Christopher KB, Brown RS Jr. Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis is a risk factor for renal failure requiring dialysis in waitlisted liver transplant candidates. Clin Transplant. (2016) 30:502–7. doi: 10.1111/ctr.12712

125. Pelletier G, Salmon D, Ink O, Hannoun S, Attali P, Buffet C, et al. Culture-negative neutrocytic ascites: a less severe variant of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. J Hepatol. (1990) 10:327–31. doi: 10.1016/0168-8278(90)90140-M

126. Hoefs JC, Runyon BA. Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Dis Mon. (1985) 31:1–48. doi: 10.1016/0011-5029(85)90002-1

127. al Amri SM, Allam AR, al Mofleh IA. Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis and culture negative neutrocytic ascites in patients with non-alcoholic liver cirrhosis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. (1994) 9:433–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.1994.tb01269.x

128. Li H, Wieser A, Zhang J, Liss I, Markwardt D, Hornung R, et al. Patients with cirrhosis and SBP: increase in multidrug-resistant organisms and complications. Euro J Clin Invest. (2020) 50:e13198. doi: 10.1111/eci.13198

129. Rostkowska KA, Szymanek-Pasternak A, Simon KA. Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis - therapeutic challenges in the era of increasing drug resistance of bacteria. Clin Exp Hepatol. (2018) 4:224–31. doi: 10.5114/ceh.2018.80123

130. Oey RC, de Man RA, Erler NS, Verbon A, van Buuren HR. Microbiology and antibiotic susceptibility patterns in spontaneous bacterial peritonitis: a study of two dutch cohorts at a 10-year interval. United Euro Gastroenterol J. (2018) 6:614–21. doi: 10.1177/2050640617744456

131. Tang C, Wu X, Chen X, Pan B, Yang X. Examining income-related inequality in health literacy and health-information seeking among urban population in China. BMC Public Health. (2019) 19:221. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-6538-2

132. Buonomo AR, Zappulo E, Scotto R, Pinchera B, Perruolo G, Formisano P, et al. Vitamin D deficiency is a risk factor for infections in patients affected by HCV-related liver cirrhosis. Int J Infect Dis. (2017) 63:23–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2017.07.026

133. Buonomo AR, Arcopinto M, Scotto R, Zappulo E, Pinchera B, Sanguedolce S, et al. The serum-ascites vitamin D gradient (SADG): a novel index in spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. (2019) 43:e57–60. doi: 10.1016/j.clinre.2018.10.001

134. World Health O. Antibiotic Resistance: Multi-Country Public Awareness Survey. Geneva: World Health Organization (2015).

135. Borenstein M, Higgins JPT, Hedges LV, Rothstein HR. Basics of meta-analysis: I2 is not an absolute measure of heterogeneity. Res Synth Methods. (2017) 8:5–18. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.1230

136. Rücker G, Schwarzer G, Carpenter JR, Schumacher M. Undue reliance on I(2) in assessing heterogeneity may mislead. BMC Med Res Methodol. (2008) 8:79. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-8-79

137. Ye Q, Zou B, Yeo YH, Li J, Huang DQ, Wu Y, et al. Global prevalence, incidence, and outcomes of non-obese or lean non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. (2020) 5:739–52. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(20)30077-7

138. Huang DQ, Yeo YH, Tan E, Takahashi H, Yasuda S, Saruwatari J, et al. ALT levels for asians with metabolic diseases: a meta-analysis of 86 studies with individual patient data validation. Hepatol Commun. (2020) 4:1624–36. doi: 10.1002/hep4.1593

139. Borges Migliavaca C, Stein C, Colpani V, Barker TH, Munn Z, Falavigna M, et al. How are systematic reviews of prevalence conducted? A methodological study. BMC Med Res Methodol. (2020) 20:96. doi: 10.1186/s12874-020-00975-3

140. Neimann Rasmussen L, Montgomery P. The prevalence of and factors associated with inclusion of non-English language studies in campbell systematic reviews: a survey and meta-epidemiological study. Syst Rev. (2018) 7:129. doi: 10.1186/s13643-018-0786-6

Keywords: chronic liver disease, cirrhosis, SBP, infection, socioeconomic status

Citation: Tay PWL, Xiao J, Tan DJH, Ng C, Lye YN, Lim WH, Teo VXY, Heng RRY, Yeow MWX, Lum LHW, Tan EXX, Kew GS, Lee GH and Muthiah MD (2021) An Epidemiological Meta-Analysis on the Worldwide Prevalence, Resistance, and Outcomes of Spontaneous Bacterial Peritonitis in Cirrhosis. Front. Med. 8:693652. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.693652

Received: 11 April 2021; Accepted: 12 July 2021;

Published: 05 August 2021.

Edited by:

Muhammad Nawaz, University of Veterinary and Animal Sciences, PakistanReviewed by:

Alejandro Piscoya, Saint Ignatius of Loyola University, PeruNadia Mukhtar, University of Veterinary and Animal Sciences, Pakistan

Copyright © 2021 Tay, Xiao, Tan, Ng, Lye, Lim, Teo, Heng, Yeow, Lum, Tan, Kew, Lee and Muthiah. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Mark D. Muthiah, mdcmdm@nus.edu.sg orcid.org/0000-0002-9724-4743; Cheng Ng, chenhanng@gmail.com orcid.org/0000-0002-8297-1569

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Phoebe Wen Lin Tay

Phoebe Wen Lin Tay Jieling Xiao

Jieling Xiao Darren Jun Hao Tan1†

Darren Jun Hao Tan1†  Cheng Ng

Cheng Ng Marcus Wei Xuan Yeow

Marcus Wei Xuan Yeow Eunice Xiang Xuan Tan

Eunice Xiang Xuan Tan Mark D. Muthiah

Mark D. Muthiah