Explainer: Michelin’s ‘responsabilisation’

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

What is “responsabilisation”?

The term roughly translates into English as a mixture of empowerment and accountability. It is Michelin’s name for shifting more operational responsibility to workers.

When was it introduced?

Michelin traces the roots of the programme back many years. For instance, it had already introduced flexibility to allow certain team members to step in for an absent team leader. In 2012 the company tried giving greater autonomy to entire teams. The experiment was a success, so it extended the practice to six factories in Europe and North America. In 2018,

responsabilisation

will be expanded to the whole group.

How does it work?

Michelin’s plant in Le Puy-en-Velay is one of six involved in the latest phase.

At Le Puy, a short training programme called Oser (“to dare”), prepares workers for the switch. They learn, for example, the basics of teamwork, how to manage conflicts, how to communicate in non-confrontational ways, and how to structure a project.

Team leaders step back from issuing detailed orders on how to organise production, or providing solutions to difficult situations. Instead they act as coaches or, in the event of a disagreement, referees.Based on a weekly programme of production, and information such as planned absences and holidays, workers in the 10-strong teams divide responsibility between themselves. For example, one team member manages production, another oversees safety, a third, quality control. Together, they evaluate their own performance and liaise with other autonomous teams in the factory.

The teams work within a framework, which includes the vision and values of the group and the behaviour expected of Michelin staff, as well as hard constraints such as availability of resources and legal and safety rules.

A group of managers — known as explorateurs (explorers) — looks at ways to extend the programme.

What are the limits to independence?

Group strategy is still decided at the top by the chief executive and executive committee. But some teams are already examining how they can handle more sensitive non-production problems, such as recruitment, incentives and rewards.

What are the results?

Workers at Le Puy say people are more engaged with their work, they deal with production line problems more quickly, and they find their jobs more interesting.

Le Puy’s production has increased every year since 2013. Jean-Dominique Senard, chief executive, believes widening the programme will help the whole company become more agile.

What are the risks?

Some managers may resent losing status and power. Some workers have objected that the granting of limited independence is a cheap alternative to increasing wages. Union representatives at Ballymena in Northern Ireland — one of the six Michelin factories chosen for the trial — point out that operational responsibility did not protect the plant from a planned closure by 2018, which Michelin blamed on competition, overcapacity in the truck tyre market, and high energy and logistics costs.

How different is Michelin’s programme from previous management initiatives?

Giving decision-making power to front-line workers is not unusual.

Taichi Ohno

, chief production engineer at Toyota when it introduced the Toyota Production System after the second world war, insisted that teams should work out how to solve production line problems themselves. He called it “autonomation” or “automation with a human touch”.

Separately, Vineet Nayar, then chief executive, inverted the hierarchy of HCL Technologies, the Indian information technology outsourcing company, 10 years ago with an “

employees first, customers second

” approach that put managers at the service of valuable front-line staff.

Do other companies experiment with

responsabilisation?

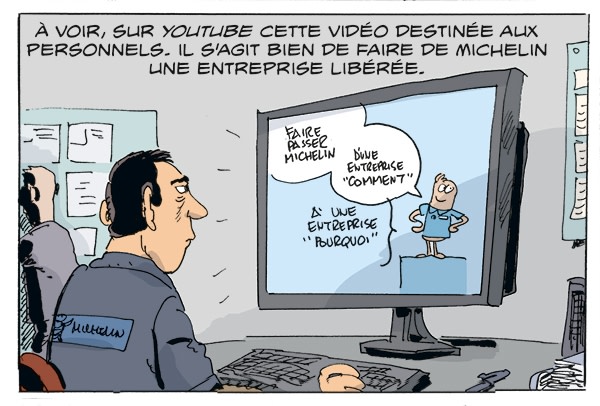

Advocates of

enterprises libérées

, such as Isaac Getz, a professor at ESCP Europe business school, regard the Michelin programme as part of a wider movement towards giving workers more autonomy. Some small- and medium-sized companies in France and Belgium have gone further, dismantling hierarchy altogether.

In the US, Tom Peters, the management writer, evangelised for “liberation management” as early as 1992, in his lengthy book of the same name. US companies working along these lines include WL Gore, manufacturer of Gore-Tex fabric, and Harley-Davidson, the motorcycle group.

The movement has its sceptics, who point out that abolishing structure can lead to “a new type of servitude”, increased infighting and a greater risk of employee burnout. But other big French companies such as privately owned Decathlon, the sports equipment retailer, are now pressing ahead with programmes of libération. In the ultimate accolade, the movement has inspired a French comic book, les Enterprises Libérées, by Philippe Bercovici and Benoist Simmat.

Comments