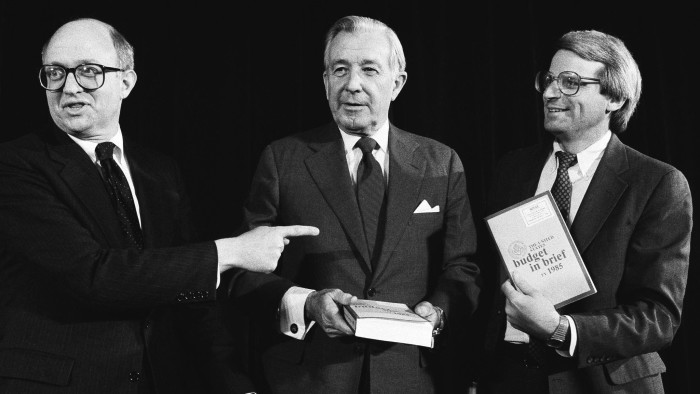

Martin Feldstein, economist, 1939-2019

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Martin Feldstein was among the most respected and influential US economists of his generation. He was a conservative, believing firmly in low taxes and small government. He was also a principled man, adhering to the highest standards of rigour and devotion to the evidence.

Feldstein (always known as Marty), who has died at the age of 79, gained the respect of scholars and policymakers across the political spectrum for his intellectual achievements and institutional creativity. He built bridges between people and positions. He was a brilliant teacher: half of the undergraduate class at Harvard took his introductory course in economics and a number of influential economists are his former students.

In person, he was unfailingly kind, polite and positive. As an economist, he was no desiccated technician: he was convinced of the power of economics to understand the world.

Educated first at Harvard College and then Oxford university, where he obtained his doctorate in 1967, while at Nuffield College, Feldstein was a firm anglophile. He will be much missed by his many friends, of whom I was one.

I met Marty first when I was a student at Nuffield, between 1969 and 1971. I had the pleasure of meeting him subsequently in many different contexts. Among them was a remarkable conference on “Economic and Financial Crises in Emerging Market Economies” that he organised in Woodstock, Vermont, in October 2000, not long after the Asian financial crisis. I also met him regularly at the annual China Development Forum. A patriotic American, he always held a global view. He was also unfailingly enjoyable and thought-provoking.

Feldstein had a significant career in public policy, the highest point being his service as chairman of then US president Ronald Reagan’s council of economic advisers from 1982 to 1984. He was publicly opposed to the facile “supply side economics” of that era (and today’s), which held that tax cuts would pay for themselves. He argued, instead, for tax increases. Although the view that deficits and debt matter put him outside the Republican party’s mainstream, to his credit, he never bent those views to the political fashion.

Feldstein’s macroeconomic analysis was mainstream, even Keynesian, and always empirically grounded. In 2005, he was viewed as a leading candidate to succeed Alan Greenspan as chairman of the Federal Reserve — a position that went to Ben Bernanke.

He also worked across political divides, serving as a member of the Economic Recovery Advisory Board set up by Barack Obama during his presidency. But his policy positions, notably his commitment to the partial privatisation of social security, which influenced Mr Obama’s predecessor, George W Bush, put him firmly on the conservative side. Yet in 2017, he joined a number of other leading US conservatives arguing for carbon taxes to be remitted directly to the American people.

Bold in public debate, Feldstein in 1997 published what swiftly became a notorious commentary on the idea of the European single currency for Foreign Affairs. In it, he argued that the creation of a single currency could lead to severe intra-European frictions, even war: “conflicts over economic policies and interference with national sovereignty could reinforce longstanding animosities based on history, nationality, and religion”.

A different contribution was less controversial, but hugely influential: the paper on savings and investment he published with Charles Horioka in 1980, which showed a high correlation between domestic savings and investment. This shows that savers have a strong home bias. As Feldstein pointed out in more recent writings, to the extent that it is not true, current account deficits and surpluses must emerge — a point not grasped, alas, by the Trump administration.

Feldstein’s academic career was made at Harvard, where he was on the faculty from 1967, becoming the George F Baker professor. He published more than 300 research articles, as well as many contributions to newspapers, including the Financial Times. His academic work covered health economics (the topic of his doctorate), international economics and the economics of national security. But the focus of his work was on public finance, social insurance and macroeconomics. He was also a pioneer in the use of large data sets to study behaviour.

In 1977, Feldstein won the John Bates Clark Medal of the American Economic Association — an award given to the economist under the age of 40 judged to have made the greatest contribution to the science. He was president of the AEA in 2004.

Yet arguably, his greatest professional achievement was his presidency of the National Bureau of Economic Research from 1977 to 2008 (with the exception of 1982-84). He turned this organisation into the most important promoter and publisher of empirical research on economics in the world. Most leading applied economists in North America are now associated with NBER.

Born in New York to a Jewish family, Feldstein met his wife Kathleen (Kate) Foley, another economist, at Oxford. They married in 1965 and had two daughters and four grandchildren.

Comments