Twenty years after his novel “Fight Club,” came out, Chuck Palahniuk took to a new form to create a sequel. With the help of friends, he decided to dabble in comics.

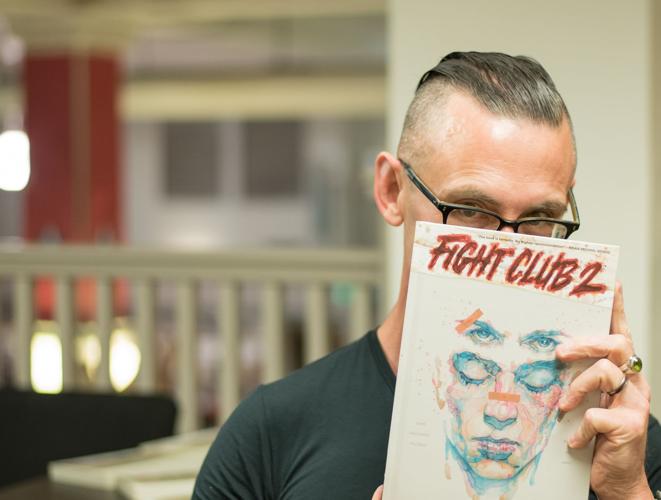

Palahniuk appeared at Auntie’s Bookstore downtown for a book signing of his new graphic novel, ‘Fight Club 2.’

Gonzaga Bulletin: Did you end “Fight Club” with the narrator remaining alive anticipating a sequel?

Chuck Palahniuk: For years, I had sworn that I’d never write a sequel, but I had the opportunity to do comics, and I really wanted my debut to be something that would be readily recognized by people — I didn’t want to create something entirely new in an entirely new form. So I thought even if I screwed up storytelling with comics, at least it would be a story that people were already familiar with and engaged with. “Fight Club” seemed like a really good, safe vehicle for this new storytelling.

GB: What led you toward the graphic novel?

CP: There is a thriller writer named Chelsea Cain who appears in “Fight Club 2” as a part of my writing group and Chelsea threw a dinner party and she invited some of the most famous people in comics who happened to live in Portland — Brian Michael Bendis, Kelly Sue DeConnick and her husband Matt Fraction — and the group of them all kinda ganged up on me and said, “You’ve gotta write comics, and we will teach you how to do it.” With that kind of support, I felt kind of roped into it. I had so many people helping — that’s why I started. Also, for the first time in a long time, I had two years free to learn a new storytelling form … that gave me the free time to learn comic script writing.

GB: What can readers expect to see in the sequel “Fight Club 2”?

CP: It was a chance to redeem fathers, because the first book was really so brutal about fathers, and this was a chance to make the protagonist a father, and show him becoming an even worse father than he had considered his own father. It was a chance to expand the story out of just a single aberrant period in one person’s life, to expand it into the past and into the future and make more of a long-term mythology out of it — the way that Neil Gaiman or Stephen King would use one story as a springboard for a mythology that stretches forever into both the past and the future. So, it makes a larger story out of [“Fight Club”]: It revisits a lot of the secondary characters people really loved. Originally, it didn’t. I left Big Bob dead, I left Chloe dead — but then I found out how much readers really loved those characters and wanted to see them back, so I wrote them back to life.

GB: How did you get into writing?

CP: My degree is in journalism. When I got out of school, I worked for a small community newspaper that published twice a week, and the pay was terrible: It was $5 an hour, and I eventually had to quit because of my student-loan debt. I started working for Freightliner, building trucks in their Portland truck plant. I dummied up a fake resume, I got an assembly line job and that’s more or less what I did for 13 years. What I wanted to do originally was write fiction, not journalism, so I started taking a class that was offered by a Portland novelist, a man who had just moved from New York and taught initially for students around his kitchen table, and we paid $20 a week to sit and have these lessons. He taught us what he learned getting his MFA at Columbia, so this man, Tom Spanbauer, coached me in this style of minimalism and I basically got an MFA for $20 a week through Tom. I eventually wrote “Invisible Monsters” first, which I couldn’t’ sell, and then I wrote “Fight Club,” which did sell. Tom put me in touch with his agent, and so that got me an agent, and that’s how I started.

GB: Where do you find character inspiration?

CP: I don’t think a character is anything but a kind of strategy for surviving. What have you kind of crafted in order to get it by? Generally, people come up with a strategy very early in life: they’re gonna be the funny person, they’re gonna be the pretty person, they’re gonna be the strong person or they’re gonna be the hardworking or the smart person, and they do that relentlessly. They’re always the clown, or the beauty queen, or the jock, until their late 20s-early 30s, and then they recognize they’re gonna be trapped being the fool and they start to hate it. That’s when their strategy starts to break down. So what happens [as] this lifelong strategy breaks down is typically where I start for character. It’s where you give up that kind of “child-you” and [it’s] how successfully you transition into a new strategy. That’s what so many great books are about. “Invisible Monsters” is about a woman who is always traded on her beauty and so she intentionally destroys it to force herself to kind of find a new form of power. That’s what, for me, character has always been about: what form of power a character utilizes in the world, and how they are able to bridge to a different form of power as the old form of power loses its effectiveness.

GB: What is your favorite work that you’ve done?

CP: “Beautiful You,” just because it was such a fantastic joy to write really bad modernist fiction instead of minimalism. It’s kind of heartbreaking because among the students I’ve taught, the impulse is always to tell their most emotionally intense personal story as the first thing that they write, but the problem is they have so few writing skills that they’re writing their most powerful story and they’re writing it so poorly that it inadvertently occurs as comic. When you write powerful material with very little skills, it becomes this unintentional comic piece, and that’s what I wanted to do with “Beautiful You,” was to write something really powerful but to write it really poorly. That disconnect creates a strange comedy.

GB: What piece of advice would you give to aspiring writers?

CP: Find the thing that nobody is talking about, that no one will bring themselves to talk about, and find a metaphorical way to present it because people will attach to it then, because it expresses some unexpressed part of their awareness. They might not understand why they attach to it so passionately, but they’ll attach to it. Always find the thing that people can’t talk about and then create a metaphor that allows people to explore the idea on almost a subconscious level.

GB: If you could describe “Fight Club 2” in only one word, which would you use?

CP: Kinetic.