Autoimmune Rashes: Causes, Treatments, Pictures, and More

Key takeaways:

Autoimmune diseases commonly show up in the skin as different rashes.

Skin changes and rashes may be the first sign of an underlying autoimmune disease.

Treatment for autoimmune skin conditions involves treating the underlying condition. Sun protection is also key for many of these conditions.

Access savings to related medications

Table of contents

The skin is the largest organ in your body, and it can tell you a lot about your health. Many different autoimmune conditions can affect your skin and cause rashes. In fact, these skin changes may be the first — or only — symptoms you see.

Your skin is an important part of your immune system. It has many different cells that identify and target unwanted invaders (like bacteria). And it’s constantly communicating with other cells in your body.

With an autoimmune condition, your immune system mistakenly attacks normal parts of your body. And your skin can be a target for that attack. Some autoimmune conditions, like alopecia areata, only affect the skin. Others can affect the skin as part of a multisystem disorder (one that affects many parts of the body). Rheumatoid arthritis is just one example.

Because your skin is so visible, a skin rash may be the first sign of an underlying autoimmune disorder.

What does an autoimmune rash look like?

There’s no single autoimmune rash. Different autoimmune conditions cause different skin changes and symptoms.

Some symptoms are commonplace, like itchy skin and a change in skin color. Other symptoms may be more specific to the underlying condition.

Here are some common symptoms of autoimmune rashes:

1. Pink, red, violet, or brown rashes: On darker skin, rashes can look more violet or brown. On lighter skin, they tend to be pink or red.

2. Scaly patches: These can be white or gray and patchy or pretty thick.

3. Open sores: These can happen on the skin, but they’re also common inside the mouth or in the genitals.

4. Blisters in the skin: Blisters can be small or large. And, depending on the cause, they can be firm to the touch or break easily.

5. Crusty skin: Crusty patches are often associated with rashes, blisters, or open sores.

To get the right diagnosis, you may need to see a dermatologist or healthcare professional with skin expertise. This may require a skin biopsy, an in-office procedure that removes a small piece of tissue. Below, we’ll discuss common skin changes seen in certain autoimmune diseases.

Autoimmune rashes on the face

Two autoimmune diseases — lupus and dermatomyositis — cause rashes that can affect the face in different ways.

Lupus

Lupus is a chronic autoimmune disease that most commonly affects women ages 15 to 44. There are a few different types of lupus. In addition to the skin, systemic lupus affects many organs and structures, like the:

Kidneys

Joints

Heart

Blood vessels

The first sign of systemic lupus is a butterfly rash on the face. This pink-red or violet-brown rash gets its name from its butterfly shape across the cheeks and the bridge of the nose. In some people, it can itch or hurt, and it’s often mistaken for sunburn.

Cutaneous lupus is another form of lupus. It mainly affects the skin and has two main types of rash:

Subacute cutaneous lupus: This causes round patches on skin that’s exposed to the sun. These scaly patches can be red, violet, or brown in color.

Discoid lupus: This causes thick, discolored, and scaly patches on the face, scalp, or ears. They can be associated with hair loss and be brown, pink, or white in color.

If you have lupus that involves your skin, your care team may order more tests, like blood work. This is to make sure you don’t have systemic lupus.

Dermatomyositis

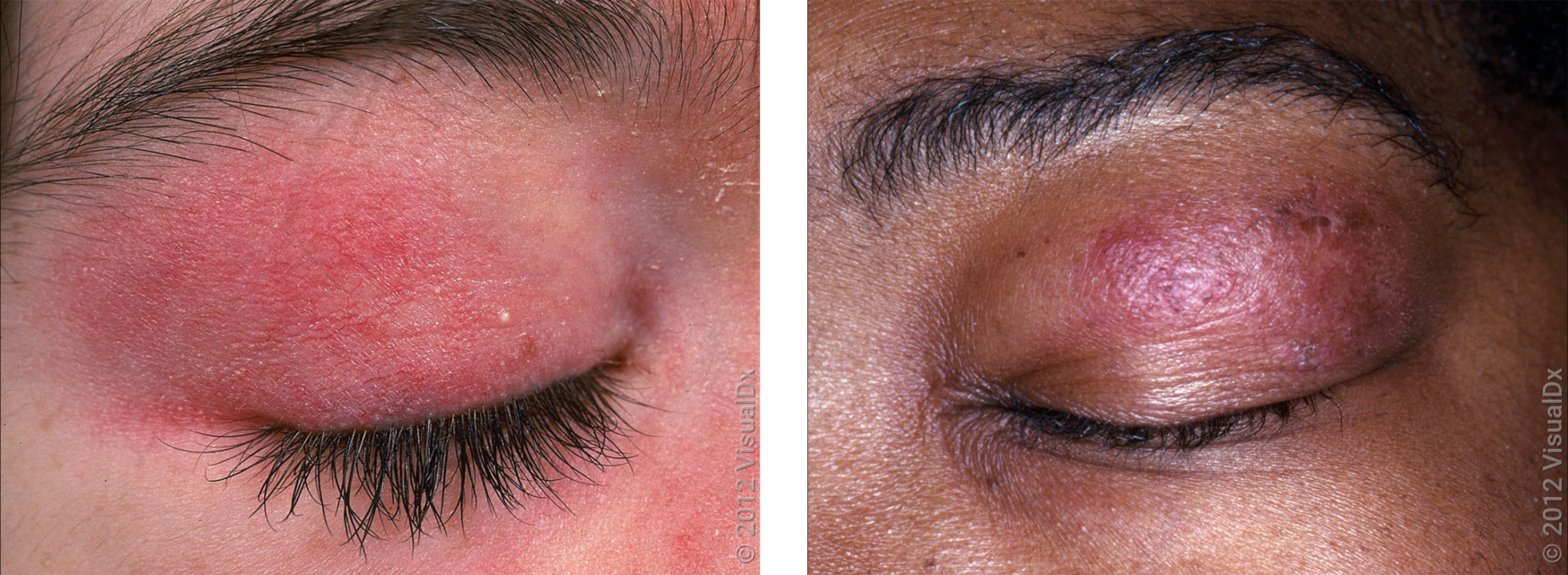

Dermatomyositis is a rare autoimmune disease that causes muscle weakness and skin changes. Sometimes it can cause difficulty breathing or a cough. It usually affects children between the ages of 5 and 15 and adults between the ages of 40 and 60.

One early sign of dermatomyositis is a heliotrope face rash. This is a reddish-purple to brown-violet rash on the eyelids.

Dermatomyositis can also cause skin changes on other parts of the body. This can include:

Red, pink, or purple bumps on the outer joints of the hand, knees, or elbows

Red, violet, brown, or discolored skin on the chest, shoulders, neck, and upper back (sun-exposed areas)

There’s no cure for lupus or dermatomyositis. But different medications that lower the immune response can help manage symptoms.

Blisters in the skin

Many autoimmune diseases cause skin blisters. Blisters can look different depending on what part of the skin is involved. Sometimes these can be large, firm, and full of fluid. They can also be small and form yellow crusts. It depends on the underlying autoimmune condition.

Dermatitis herpetiformis

Dermatitis herpetiformis is a chronic autoimmune skin condition that happens as a reaction to eating gluten. Gluten is a protein in many foods, like wheat and rye.

Dermatitis herpetiformis is related to Celiac disease. Between 10% and 15% of people with Celiac disease get a dermatitis herpetiformis skin rash. This rash usually starts in people between the ages of 30 and 40 as extremely itchy blisters and red to violet bumps and sores on the:

Elbows

Knees

Buttocks

Scalp

Many people also experience:

Stomach pain

Cramping

Diarrhea

In some people, the symptoms come and go, which can make it harder to diagnose.

Treatment includes removing all gluten from the diet. Some medications can also help (more about treatments below).

Pemphigoid

Pemphigoid is a group of rare autoimmune diseases that form blisters in the skin. The most common one is called bullous pemphigoid. It usually affects people over the age of 70.

Bullous pemphigoid causes itchy, firm blisters on any part of the skin, including the mouth or the genitals. Some people will have just a few spots while it can cover large parts of the body in others.

Neurologic diseases — like dementia and Parkinson’s disease — are more common in people with bullous pemphigoid.

There are different medications that can help treat pemphigoid. For many people, the rash will go away on its own after a few years.

Pemphigus

Pemphigus is another group of rare autoimmune diseases that form blisters in the skin. But it’s quite different from pemphigoid. Pemphigus vulgaris is the most common one, and it usually affects middle-age and older adults.

Most people get small blisters that are red, violet, or brown. The blisters break easily but don’t itch. This causes ulcers and sores that can join together and be quite painful. Often the blisters start in the mouth and then spread to any part of the skin. Some people will have fewer blisters. Others will have large areas of skin involved.

In darker skin, pemphigus can leave light or dark patches in the skin (post-inflammatory hypo- and hyperpigmentation) that can take months to fade.

People with pemphigus may also get skin infections where there are blisters. In some people, pemphigus vulgaris can become life-threatening if it’s not treated.

There’s no cure for pemphigus, but there are good treatments that can control symptoms.

Thick or hardened skin

Some autoimmune rashes, like psoriasis and scleroderma, can cause a change in the skin’s thickness or texture. In some situations, they can also affect other parts of the body.

Psoriasis

Psoriasis is a common autoimmune disease that affects about 3% of adults in the U.S. It’s a chronic condition that causes patches of skin to grow too quickly.

There are different types of psoriasis; plaque psoriasis is the most common. In lighter skin tones, this causes red patches with thick, white scales. In darker skin tones, the patches can be violet or brown with gray scales. These patches usually affect the:

Elbows

Knees

Lower back

Beyond the skin, people with psoriasis can also have other conditions, like:

Psoriatic arthritis, which causes painful, swollen joints

Heart disease

Psoriasis is usually a life-long condition, and treatment depends on how severe the symptoms are. Treatment usually includes medicated creams and pills or shots that can help lower the immune system.

Scleroderma

Scleroderma is an autoimmune disease that causes your body to make too much collagen. Collagen is a protein in your skin and other tissues. Anyone can get scleroderma, but it usually affects women between the ages of 30 and 50. There are two main types:

Localized scleroderma (morphea) affects the skin and underlying tissue.

Systemic scleroderma (systemic sclerosis) can affect the skin and other organs, like the heart, lungs, kidneys, and blood vessels. This is the more serious type.

In both forms, scleroderma causes patches of hardened, thick skin that feel firm to the touch and can appear shiny. The patches are usually darker than normal skin, like red or brown. But they can also be lighter or white in color. They can be round and oval, or they can form lines that run down your arm or leg, or appear on your forehead.

There’s no cure for scleroderma, but treatments can help manage the different symptoms. Some people with localized scleroderma might not need treatment since the skin changes may go away on their own.

Sores in the mouth or genitals

Mouth ulcers, like canker sores, are common and usually go away on their own. If mouth ulcers keep coming back, or if you also have them on the genitals, it could be a sign of a rare autoimmune disorder called Behçet disease.

Behçet disease can happen at any age, but it usually affects people in their 20s and 30s. Experts don’t know the exact cause, but many symptoms are caused by inflammation of blood vessels. The condition can be different in each person, and it’s common for symptoms to come and go. Some other symptoms include:

Skin rashes (acne-like spots, blisters, or painful, firm bumps)

Eye problems (like blurred vision, pain, or sensitivity to light)

Pain in the joints

Diarrhea

Headaches

There’s no cure for Behçet disease, but symptoms can usually be managed with different medications. In some people, the symptoms will go away for a period of time (a remission), and treatment may not be needed for a while.

Keep in mind that other autoimmune diseases can also cause sores in the mouth or genitals, including lupus and pemphigus. So it’s a good idea to visit your primary care provider or dermatologist so they can help find the underlying cause.

Treating autoimmune skin rashes

The most important part to treating autoimmune rashes is to treat the underlying cause. Most medications work by lowering inflammation and the immune response. When just small amounts of skin are affected, it may be possible to just use medicated creams or lotions. Pills or shots are more common when larger areas of skin or other organs are involved.

Here are some common medications used in autoimmune diseases:

Corticosteroids help block inflammation and can be used to treat most autoimmune diseases. They come as medicated creams, injections, or pills.

Methotrexate (Rheumatrex) is a pill that helps to lower the immune system. It is used to treat many autoimmune diseases, including lupus, dermatomyositis, psoriasis, pemphigus, and pemphigoid.

Hydroxychloroquine (Plaquenil) is a pill that’s usually used to treat malaria infection, but it also works well to treat lupus.

Dapsone (Aczone) is a pill that’s usually used to treat certain infections, but it works well to treat dermatitis herpetiformis.

Biologics are newer medications that block specific molecules in the immune system. Most are given as shots. Etanercept (Enbrel) is used to treat psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis. Rituximab (Rituxan) is used to treat pemphigus vulgaris. Belimumab (Benlysta) is used to treat systemic lupus.

Do any over-the-counter treatments work?

It depends. Some over-the-counter products can help, but they may not be strong enough to use as the first treatment. In certain situations, products with these ingredients may help:

Hydrocortisone is a low-strength steroid cream that may help with some mild rashes that occur in autoimmune disease.

Salicylic acid, urea, or coal tar can help treat psoriasis.

Calamine or menthol can help soothe some rashes that itch.

Sun protection if you have an autoimmune condition

Sun protection is an important part of treatment for many autoimmune rashes, especially lupus and dermatomyositis. Even a small amount of sun exposure can worsen skin symptoms. So it’s important to wear sunscreen of at least SPF 30 every day.

Psoriasis is one autoimmune condition where ultraviolet (UV) light is used as a treatment (phototherapy). While natural sunlight may help with symptoms, it’s not always recommended. Talk with your primary care provider or dermatologist about what’s right for you if you have psoriasis.

Keep in mind that some medications used to treat autoimmune diseases can also make you more sensitive to the sun.

The bottom line

Autoimmune diseases can show up in the skin as different types of rashes. These skin changes may be the first sign of an underlying condition. So it’s important to see your primary care provider or dermatologist to get a diagnosis and the right treatment.

Images used with permission from VisualDx (www.visualdx.com).

References

American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology. (2020). Immunosuppressive medication for the treatment of autoimmune disease.

American Academy of Dermatology Association. (n.d.). Pemphigus: Diagnosis and treatment.

American Academy of Dermatology Association. (n.d.). Pemphigus: Signs and symptoms.

American Academy of Dermatology Association. (n.d.). Psoriasis: Overview.

American Academy of Dermatology Association. (n.d.). Scleroderma: Overview.

American Osteopathic College of Dermatology. (n.d.). Aphthous ulcer.

American Osteopathic College of Dermatology. (n.d.). Biopsy.

American Osteopathic College of Dermatology. (n.d.). Dermatomyositis.

Carter, E. L. (2003). Autoimmune diseases of the skin: Pathogenesis, diagnosis, management. JAMA Dermatology.

Celiac Disease Foundation. (n.d.). Dermatitis herpetiformis.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020). Psoriasis.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022). Diagnosing and treating lupus.

Elmets, C. A., et al. (2019). Joint AAD-NPF guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with awareness and attention to comorbidities. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center. (2021). Pemphigus vulgaris. National Institutes of Health.

Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center. (2024). Behçet disease. National Institutes of Health.

Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center. (2024). Dermatomyositis. National Institutes of Health.

Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center. (2024). Morphea. National Institutes of Health.

Kridin, K., et al. (2018). The growing incidence of bullous pemphigoid: Overview and potential explanations. Frontiers in Medicine.

Ludmann, P. (2022). Lupus and your skin: Overview. American Academy of Dermatology Association.

Ludmann, P. (2022). Lupus and your skin: Self-care dermatologists recommend. American Academy of Dermatology Association.

Lupus Foundation of America. (2021). What is systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)?

Lupus Foundation of America. (2023). Lupus symptoms.

National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. (2023). Scleroderma. National Institutes of Health.

National Organization for Rare Disorders. (2018). Bullous pemphigoid.

National Organization for Rare Disorders. (2018). Dermatitis herpetiformis.

National Psoriasis Foundation. (2022). Phototherapy.

National Scleroderma Foundation. (n.d.). What is scleroderma?

Nguyen, A. V., et al. (2019). The dynamics of the skin’s immune system. International Journal of Molecular Sciences.

Stevens, N. E., et al. (2019). Skin barrier and autoimmunity—Mechanisms and novel therapeutic approaches for autoimmune blistering diseases of the skin. Frontiers in Immunology.

Vesely, M. D. (2020). Getting under the skin: Targeting cutaneous autoimmune disease. Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine.