The secret messages hidden in the Aztec Calendar

The Aztec Calendar is one of the most fascinating artifacts of the ancient world. More than just a tool for marking the passage of days, this intricate system of timekeeping is a complex interplay of cycles within cycles, a rare record of the Aztecs' profound understanding of the cosmos and their place within it.

It is a product of a civilization that viewed time not as a linear progression, but as a series of interconnected cycles, each with its own significance and meaning.

The calendar's intricate design and symbolic imagery reflect the Aztecs' cosmological beliefs and their intricate understanding of the natural world.

Where did the Aztec calendar come from?

The roots of the Aztec Calendar can be traced back to earlier Mesoamerican civilizations, notably the Olmec and the Maya, who had developed sophisticated systems of timekeeping long before the rise of the Aztec Empire.

These early calendars, which combined lunar and solar cycles in complex ways, laid the groundwork for the development of the Aztec Calendar.

The Aztec Calendar, as we understand it today, was likely adopted and refined by the Aztecs from these earlier Mesoamerican systems after they settled in the Valley of Mexico in the 14th century.

The Aztecs, or Mexica as they called themselves, were relative latecomers to the region, and they absorbed much of the cultural and scientific knowledge of the civilizations that had preceded them.

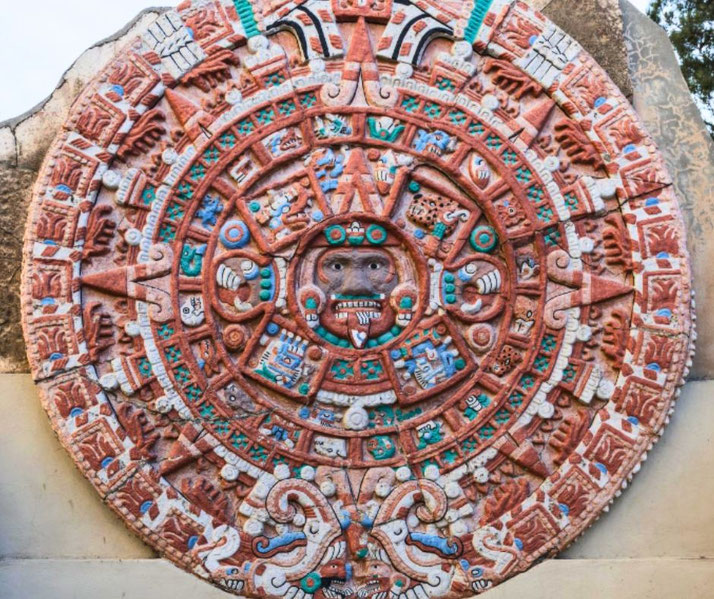

The most famous representation of the Aztec Calendar is the Sun Stone, a massive carved disk discovered in Mexico City's main square, the Zócalo, in 1790.

This monumental sculpture, often mistakenly referred to as the "Aztec Calendar," is in fact a ceremonial basin or possibly a sacrificial altar.

However, it does contain a detailed and complex representation of the Aztec cosmological and calendrical systems, making it a key artifact for understanding the Aztec Calendar.

The incredible sophistication of its design

The Aztec Calendar, often referred to as the Mesoamerican Calendar, is not a single system but rather a combination of two distinct but interlocking calendars: the Tonalpohualli, or sacred calendar, and the Xiuhpohualli, or solar calendar.

The Tonalpohualli, also known as the 260-day calendar, is the oldest of the two systems and is thought to have originated with the Olmec civilization.

It consists of 20 day signs and 13 numbers, which rotate to create a cycle of 260 unique days.

Each day has a specific name and symbol, and each has its own divinatory and ritual significance.

The Tonalpohualli was used primarily for religious and divinatory purposes, and it played a central role in Aztec rituals and ceremonies.

The Xiuhpohualli, or 365-day solar calendar, is similar to our modern calendar in that it follows the solar year.

It is divided into 18 "months" of 20 days each, with an additional 5 "unlucky" days at the end of the year, known as Nemontemi.

These were considered to be a dangerous time when the boundaries between the world of the living and the world of the dead were particularly thin.

The Xiuhpohualli was used for practical purposes such as agriculture and taxation, and each of its 18 months was associated with a specific festival.

The Tonalpohualli and the Xiuhpohualli interlock to create a 52-year cycle known as the Calendar Round or Xiuhmolpilli.

This was considered a full cycle of life, and its completion was marked with a New Fire ceremony, a major event that involved extinguishing and relighting all the fires in the Aztec realm.

What each of the symbols mean

The Aztec Calendar is rich in symbols and iconography, each element carrying profound meaning and significance within the Aztec cosmological view.

The most famous representation of this calendar, the Sun Stone, is a treasure trove of Aztec symbolism.

At the center of the Sun Stone is the face of the sun god, Tonatiuh, representing the current era, or the "Fifth Sun."

His tongue, shaped like a flint knife, juts out, signifying the sacrificial nature of this era.

Surrounding Tonatiuh are four squares representing the four previous eras or "suns," each associated with a different deity and a different form of destruction.

The next ring contains the 20 day signs of the Tonalpohualli, each with its own unique symbol.

These include animals such as the jaguar and the eagle, natural elements like water and wind, and more abstract concepts like death and movement.

Each day sign was associated with a particular deity and had its own set of characteristics and meanings.

Beyond the day signs, there are two fire serpents that encircle the stone, their tails at the bottom and their bodies rising up on either side to meet at the top.

These serpents represent time and the cycles of the universe. Between them, at the top of the stone, is a date, "13 Reed," which is believed to be the coronation date of the Aztec emperor Moctezuma II.

The outermost ring of the stone is composed of two Xiuhcoatl, or fire serpents, representing the transformation of the earth.

The serpents' tails are at the bottom of the stone, and their bodies, covered in star symbols, rise up on either side to meet at the top, where they are joined by a single head.

The hidden astronomical calculations of the calendar

The calendar's intricate cycles and interlocking systems required a high level of mathematical precision and a detailed knowledge of the movements of celestial bodies.

The Tonalpohualli, or 260-day calendar, is thought to have been based on the cycle of Venus, one of the most visible celestial bodies in the sky.

The number 260 also has many factors, making it a versatile number for a calendar system that needs to align with other cycles.

The interplay of the 20 day signs and the 13 numbers in the Tonalpohualli creates a cycle of 260 unique days, demonstrating a sophisticated use of mathematical principles.

The Xiuhpohualli, or 365-day solar calendar, reflects the Aztecs' accurate observation of the solar year.

This calendar was used for practical purposes such as agriculture, demonstrating the Aztecs' understanding of the seasons and their ability to apply their astronomical knowledge to everyday life.

The Aztec Calendar is a remarkable example of the integration of mathematics and astronomy in ancient cultures.

It demonstrates the Aztecs' ability to observe and understand the natural world, and to apply this knowledge in a practical and meaningful way.

What happens when the calendar ends?

The end of the Calendar Round was a time of great anxiety for the Aztecs, as it was believed that the world might end with the completion of the cycle.

According to Aztec cosmology, the current era, or "Fifth Sun," was the latest in a series of world ages, each of which had ended in a cataclysmic event.

The end of the Calendar Round was seen as a potential time for the next world-ending event.

To prevent this, the New Fire ceremony was held at the completion of each Calendar Round.

During this ceremony, all fires in the Aztec realm were extinguished, symbolizing the end of the old world.

A new fire was then kindled in the chest of a sacrificed person, representing the birth of the new world.

This new fire was used to relight all the fires in the community, symbolizing the renewal of life for another 52-year cycle.

In recent times, the concept of the end of the Aztec Calendar cycle has often been misunderstood or misrepresented, particularly in relation to the "2012 phenomenon," which incorrectly associated the end of a cycle in the Maya Calendar (a calendar system related to the Aztec Calendar) with the end of the world.

However, for the Aztecs, the end of the Calendar Round was not a prophecy of apocalypse, but a time of renewal and rebirth, a testament to their belief in the cyclical nature of time and the cosmos.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2024.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.