Acacia senegal

Description 5

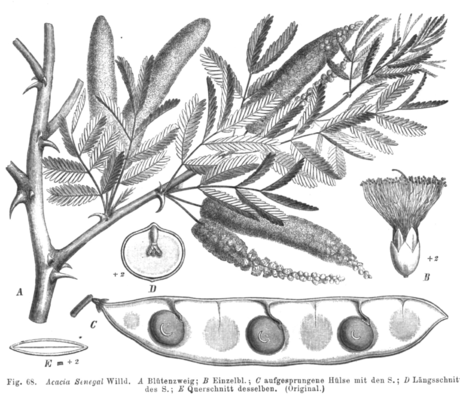

A small tree, 3-6 m. tall, young shoots pubescent, old branches glaucous-grey, on older stems the bark peels off in thin flakes of a darker colour. Prickles in threes at the base of the petiole, two lateral ones nearly straight or slightly curved upwards, the third recurved c. 5 mm long. Rachis c. 2.5-5 cm long, with glands between the lowest and upper most pair of pinnae. Pinnae 3-5 pairs, opposite, sometimes alternate, c.1.2-2.5 cm long. Leaflets 8-15 pairs, c. 2-5 mm long, c. 1-1.5 mm broad, linear, obtuse, subsessile. Inflorescence a pedunculate spike, peduncle c. 8-18 mm long, spike 5-10 cm long. Flowers sessile. Calyx c. 1.5-2.5 mm long, broadly campanulate, glabrous. Corolla c. 4 mm long. Stamens indefinite, filaments c. 6-7 mm long. Pod 5-7.5 cm long, c.1.7-2.5 cm broad, thin, flat, almost straight, shortly stipitate, tip with a slightly curved beak. Seeds 5-6, disc like, almost circular, ovate to linear-ovate, 6-9 mm long, c. 5-8 mm broad, with a U shaped depression on either side, smooth, dark brown to greyish green in colour.

Uses and economic significance 6

Acacia senegal is a highly valued tree originally from the Sudan region of Africa (Encyclopedia Britanica Online Academic Edition 2012). A. senegal is native to the Sahel regions of Africa and the Middle East and is the chief source of income for semi-nomadic people in the region, who harvest it from wild plants, but trees are also grown commercially in plantations and in state forests (Anderson 1995).

Its most recognizable product is gum arabic. Gum arabic is a significant global commodity because of its many industrial and culinary uses (Bennett 2007). Gum is obtained by cutting the bark of the tree near the start of the dry season so that it will undergo gummosis, a process that is usually naturally triggered after the bark has been damaged by a bacterial or insecticidal attack (Encyclopedia Britannica Online Academic Edition 2012). The harvesting period is throughout the dry season because gum formation requires intense heat and dehydration stress (Anderson 1995). If the conditions are met, the tree yields translucent light yellow lumps of exudate at the site of damage, these lumps are the gum arabic (Encyclopedia Britannica Online Academic Edition 2012). The exudate takes about 3 weeks to collect after the initial slit is made and can be collected several times throughout the season form the same tree (Anderson 1995). The adhesive properties and viscosity of gum arabic make it a key ingredient in many pharmaceuticals and industrial products, as well as a common food additive (Anderson 1995). Its most common uses are emulsification, binding, and coating.

The gum arabic derived from A. senegal is the only source of gum arabic that is safe to use as a food additive. It is used as a flavor fixative and emulsifier to prevent sugar crystallization in sweets, and as a stabilizer in frozen dairy products and beer foam (Cossalter 1991). A. senegal's gum arabic is highly water soluble and has a relatively low viscosity, making it an ideal baking ingredient because of its ability to act as a thickening and binding agent (Anderson 1995). As such, it is used to as a flavor fixative and caulifier in confections, and to “encapsulate dried flavors and fragrances (Booth and Wickens 1988; Anderson 1995).” It is also a key ingredient in medicated lozenges, cough syrup, and cough drops and is commonly used as an emulsifier, or as a binding coat on medicine tablets (Anderson 1995; Cossalter 1991). In cosmetics, it is added to provide adhesion in facial masks and powders, and to give smoothness to lotions (Cossalter 1991).

In traditional medicine in various parts of the world it has been to treat inflammation, nodular leprosy and dysentery, and in some parts of India, ground gum arabic mixed with wheat flour and sugar is fed to women after child birth. However small pieces of dried gum fried in fat are also used to make ordinary snacks and the gum can also be eaten with ghee or chewed by children (Booth and Wickens 1988).

Other industrial applications of gum arabic include use as a protective colloid in inks, a conservat in carbon free paper, and a protective coating on metals to guard against corrosion (Anderson 1995; Cossalter 1991). It is further employed in the production of certain fabrics, matches and ceramic pottery, and as a sensitizer in lithograph plates (Cossalter 1991). Beyond just the gum, the bark of A. senegal is tannin rich and is used in tanning, and as an ingredient in dyes, inks, and pharmaceuticals (Encyclopedia Britannica Online Academic Edition 2012). Seeds are sometimes grown as a vegetable for human consumption, lateral roots used as twine, and the wood used to make high quality charcoal (Booth and Wickens 1988).

Ecologically, A. senegal plays an important role in limiting desertification by acting as a sand dune stabilizer and wind breaker. It is a key feature of the Senegalese Sahelian savanna because herbaceous plants, whose litter is responsible for returning large portions of nitrogen to the soil, grow under A. senegal trees in dense concentration, whereas in the open savanna they are rare (Gerakis and Tsangarkis 1970). The tree itself is a nitrogen fixer and improves soil fertility but the leaf litter of associated herbaceous plants provides even more significant nitrogen return (Booth and Wickens 1988; Gerakis and Tsangarkis 1970).

Sources and Credits

- (c) Marco Schmidt, some rights reserved (CC BY-NC-SA), http://www.westafricanplants.senckenberg.de/root/index.php?page_id=14&id=32

- (c) Mark Hyde, Bart Wursten and Petra Ballings, some rights reserved (CC BY-NC), https://www.zimbabweflora.co.zw/speciesdata/images/12/126190-6.jpg

- Paul Hermann Wilhelm Taubert (1862-1897), no known copyright restrictions (public domain), https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/eb/Acacia_senegal_Taub68.png/460px-Acacia_senegal_Taub68.png

- (c) Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh, some rights reserved (CC BY-NC), http://data.rbge.org.uk/images/289987/700

- Adapted by Marco Schmidt from a work by (c) Missouri Botanical Garden, 4344 Shaw Boulevard, St. Louis, MO, 63110 USA, some rights reserved (CC BY-NC-SA), http://eol.org/data_objects/4969626

- Adapted by Marco Schmidt from a work by (c) Amy Chang, some rights reserved (CC BY), http://eol.org/data_objects/25213641