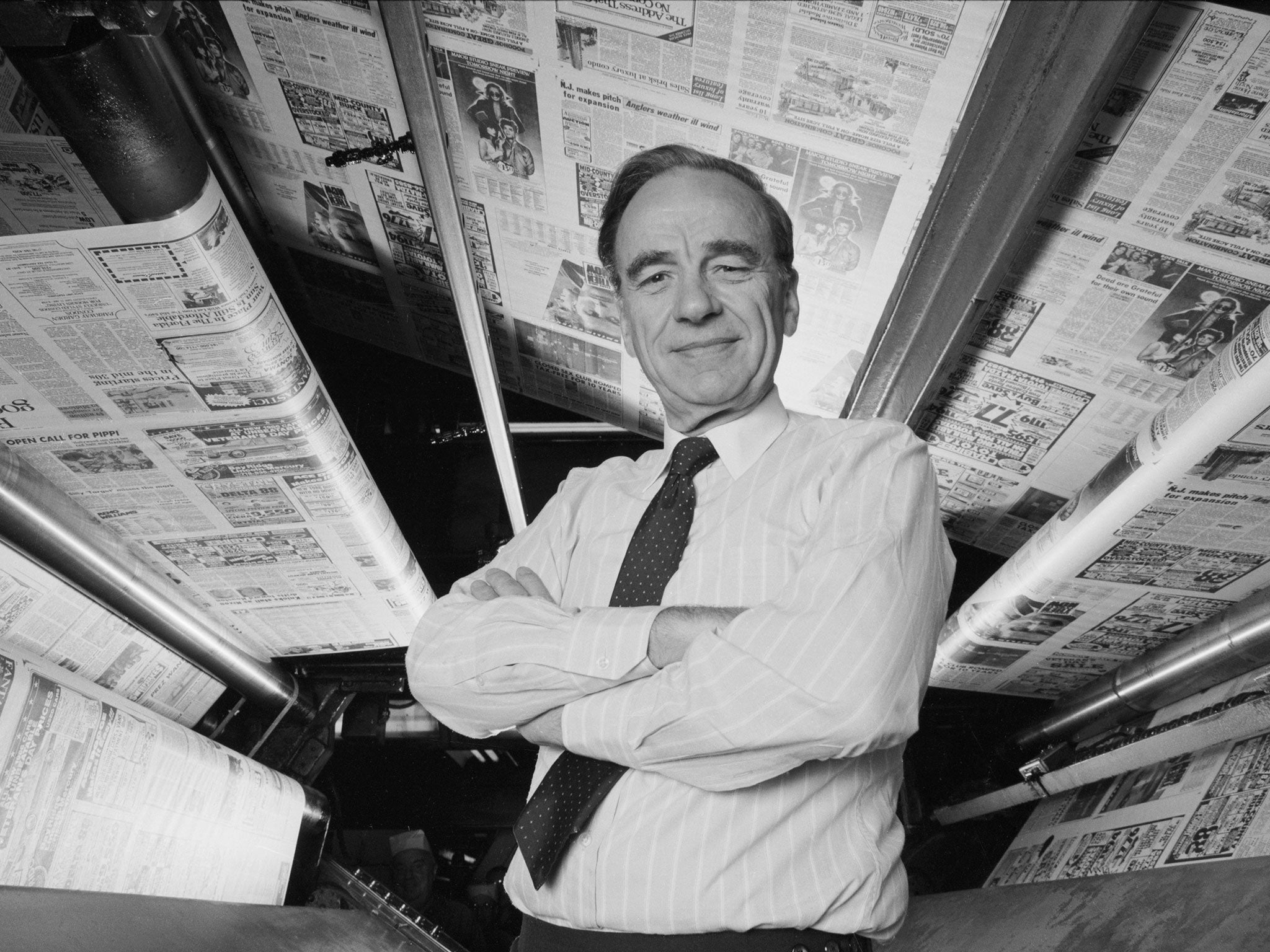

Wapping dispute 30 years on: How Rupert Murdoch changed labour relations - and newspapers - forever

Thirty years ago this weekend, Rupert Murdoch moved his papers to Wapping, firing anyone who refused to work with his new technology and fomenting ugly battles at the gates of his new plant. Most journalists acquiesced – thus helping Thatcherism win a great symbolic victory – but not Donald Macintyre, then at The Times. He reflects on those events, his part in them, and their ironic if happy dividend

It's tempting to imagine a dusty, yellowed sheet of paper bearing my unfinished – and unpublished – story still curled up in some corner of 200 Gray's Inn Road, once home to The Times and The Sunday Times. In fact, it was probably incinerated long ago. But what became of the gently spoken woman who typed it that Friday evening in January 1986?

In one of the more surreal moments of a long journalistic career, I was standing in a phone box near Kings Cross, dictating to a copytaker what I didn't yet know would be my last report to and about The Times and The Sunday Times – covering an event that would change not only both our lives but the entire newspaper industry. When I started to list the different jobs of the 5,500 workers who had been called out on strike by the print unions half an hour earlier – compositors, linotype operators, machine-room personnel, publishing-room employees, clerical staff and, yes, copytakers – there was an unmistakeable intake of breath at the other end of the phone.

"Are you ok?" I asked. "Yes, carry on," she said. Then two or three paragraphs later, she signed off with a polite but abrupt apology. "I'm sorry, I've got to go now." The soft-voiced Society of Graphical and Allied Trades (Sogat) member had presumably been called to a meeting to be told officially that she was on strike.

Of course, the edition of The Times for which the story was intended never appeared the day after. The next one, on the following Monday, would be produced without the previous workforce – who were summarily sacked – at News International's brand new plant at Wapping. And the bitter year-long dispute between Rupert Murdoch and the print unions – one of the most decisive of the era – had begun.

The story of how Murdoch had secretly made plans which enabled him to bypass the print unions and, from 27 January, produce all four of his titles – including The Sun and the News of the World – at the barbed-wire protected Wapping site has been told many times. As has that of the long and abortive negotiations that preceded the move, including Murdoch's November 1985 ultimatum that in six months he would replace existing agreements in an industry notorious for industrial disruption with one that would end strikes and impose management's unfettered right to manage. So, too, the subsequent strike call, the move to Wapping over the weekend of January 25-26 and the furious and often violent subsequent battles between the police and pickets trying – and failing– to stop workers going into the plant and the TNT lorries that distributed papers driving out.

For the journalists, Murdoch's coup posed an acute dilemma. They were crucial to his plan, which was why he offered payments of £2,000 apiece to those going to Wapping. Their alternative was the same fate as the striking print workers': the sack. New technology had already spelt the end of the 150-year-old "hot metal" newspaper production system; but even on such papers as The Sunday Times, when the latter part of the process was replaced by "paste-up" – a halfway house to the digital make-up used today – unionised linotype operators continued to set the type at Gray's Inn Road. In the Wapping plant journalists would be – for the first time – typing directly from their computers into the system.

Few journalists relished the sudden move to Murdoch's east London fortress. But for many the idea of acting in solidarity with the print workers was equally unpalatable, not least because of the frequent stoppages by different groups among them – including some of the country's highest paid industrial workers. And part of the print workers' formidable industrial strength lay precisely in the transitoriness of the product. Car production halted by a strike could be recovered with overtime; one day's newspaper production would be lost forever.

In her behind-the-scenes account of the dispute, The End of the Street, the long-time Sunday Times reporter Linda Melvern vividly describes the agonies of the National Union of Journalists (NUJ) "chapel" (or office branch) at The Times over that weekend. And in it, she quotes the chapel's "father" (chairman) Greg Neale, the courteous but unwavering champion of the NUJ's official call on its members not to go to Wapping, as saying – correctly – that the late Tony Bevins, then The Times' political correspondent, was the most "honest and brave" of those who advocated yielding to the company's demands. He was also the most effective.

In the first of two long and tense meetings on the day after the strike was called – Saturday 25 January – Bevins told his colleagues: "I want my stories to be published but yesterday was typical." The previous day he had "slogged [his] guts out" covering the Home Secretary Leon Brittan's resignation over Westland, only to see the paper not appear. But he was even more eloquent at the decisive Sunday night meeting in Bloomsbury's Marlborough Crest Hotel, combining his call to bow to what he saw as the inevitable with an excoriation of the management's tactics. "When you are faced with overwhelming pressure and you are in a cul de sac… you must either fight to the death or lie down… We have a gun at our heads. I believe most of you will go with ashes in your mouths."

Ashes or not, Bevins' prediction was correct. Earlier, the management had made a concession: having insisted that journalists would work the new technology "without any reservation", it dropped those three words. Whether that had any practical effect is debatable – but those in favour of holding out for longer were anyway in a minority, vainly trying to persuade the chapel that there were reasons other than mere inter-union solidarity for staying away from Wapping, at least for the moment.

Maybe – and maybe not – we could have exploited Murdoch's unprecedented need for journalistic co-operation by demanding he honour the guarantees of editorial independence from proprietorial interference that he had given to secure parliamentary approval of his takeover of The Times and Sunday Times four years earlier. (These were the very guarantees that Harold Evans, sacked by Murdoch as editor in 1982, says the proprietor breached within 12 months of the takeover.)

Of course such ideas were woefully inchoate – inevitably, given the suddenness with which the ultimatum had been sprung on us. Meanwhile, some of the discussions that fraught weekend were quite elevated. Cliff Longley, then The Times' eminent religious affairs correspondent, warned me at one point – citing a concept from St Thomas Aquinas – that those arguing against the move were at risk of "moral vanity". Either way, that group included The Times team covering labour relations: David Felton, Barrie Clement and myself as labour editor. I can't remember my contribution to the meeting, but Melvern quotes me as saying: "We are being bounced. You shouldn't let it happen… Every time the chapel stands firm, the telexes start clattering with fresh concessions with management… Don't imagine The Sunday Times will go. They're waiting to see what we will do."

My appeal, in other words, was no more heroic than Bevins' had been gung-ho. But it was Bevins' side that decisively won the day; The Times chapel voted by three-to-one to make the move. And The Sunday Times journalists followed suit, against the advice of their chapel father Kim Fletcher (much later the editor of The Independent on Sunday).

Melvern points out that, for Felton, Clement and me, there was a "particular dilemma": if we crossed the picket lines, our job would become almost impossible since it was unlikely any of our union contacts would speak to us. But that was only one of many factors we three had to weigh up, once the chapel had accepted the ultimatum and we had to decide whether to abide by the collective decision of our chapel or by the NUJ's instruction not to go.

Nor was it quite the whole story. As Clement later wrote, he had been swayed by all four of the reasons he ascribed to the refuseniks: "loyalty to the NUJ, sympathy for the sacked print workers, distaste for a media organisation which wielded far too much media power" and not wanting to be "pushed around by a bully offering a £2,000 bribe to cross picket lines". That Sunday evening, we met in a Goan restaurant to decide what to do the following morning. Like Neale, Fletcher, Paul Routledge and all the other refuseniks, we decided not to be part of the brave new world at Wapping. To keep our spirits up, we told ourselves that we had hadn't left The Times – it had left us.

I don't recall doing much, if any, picketing. This was partly, I think, because we were too daunted by the prospect of confronting friends and close colleagues whom we respected – and still respect – and for many of whom the decision to go into Wapping had been an agonising one; and partly – though this is a less good reason – because we were busy. In the coming months, we were luckier than most. We lived on NUJ strike pay and a generous allocation of work for the editors of various trade union journals – until the three of us were rescued by being hired, en bloc, by Andreas Whittam Smith, the editor who had the exceptional vision to found a new paper which will celebrate a happier 30th anniversary this year: The Independent.

The dispute, and the polarised world of the mid-1980s that it reflected, are commemorated in an interesting exhibition at the Tower Hamlets local history library. Among the now-rare trade union banners of florid painted silk – the one for The Sun Machine Chapel proudly carries the paper's still famous logo – the compelling photographs and the anti-Murdoch banners, you can see the infamous letter to News International from its (and the Queen's) solicitors Farrer & Co, assuring it in December 1985 that "if a moment came when it was necessary to dispense with the present workforce at [Times Newspapers Ltd] and [News Group Newspapers], the cheapest way of doing so would be to dismiss employees while participating in a strike or other industrial action". Here you can buy a copy of the vivid Wapping: The Great Printing Dispute by linotype operator John Throw. And there are copies of the strike newspaper, the Wapping Post, occasionally recalling what a different social era it was – even among supposedly progressive trade unions.

The Wapping printers never attracted the public sympathy that the striking miners had a year earlier in an equally long struggle. This was an essentially metropolitan conflict in which the high earnings and restrictive "Spanish" practices of some London printers struck few sympathetic chords across the country. But the exhibition is an attempt to redress that balance by telling "the workers' story". Ann Field, a long-time national print union official and architect of the exhibition, says the dispute was not really about new technology (over which, she says, the unions were willing to negotiate). She is adamant there was a "conspiracy" to eliminate the unions – and the jobs.

Field sees a direct line from Murdoch's victory at Wapping to the growth of his political power and the sense of impunity that made the hacking scandal (1986-2006) possible. But if Murdoch had set the unions a trap, how had they fallen so willingly into it by calling a strike? Field, now a pillar of the Campaign for Press and Broadcasting Freedom, says: "People just didn't think it [the transfer of all four papers to the Wapping site] would happen, any more than people believed the papers had been phone hacking… Of course those conducting negotiations fall out on occasions, but you don't actually expect one side simply to demolish its negotiating partner."

Yet Murdoch had already decisively consolidated his political power, and his company's sense of "impunity", in 1981 when, with the active collusion of Margaret Thatcher – and the support of the print unions – he managed to acquire The Times and The Sunday Times.

I don't at all regret not going to Wapping in 1986. But I am far from sure that a week-long journalists' pay strike five years earlier – which I supported at the time – was very smart. The then-editor, William Rees-Mogg, told me that the strike could well persuade Lord Thomson to sell the papers. He made the remark as I was interviewing him for a Times report on a Times dispute in which, as an NUJ member, I was heavily involved. (When I told him that I would have also to interview the then-NUJ chapel father Jacob Ecclestone and that the quotes of both would have to be compressed, Rees-Mogg said: "Of course. Just treat this as you would any other dispute." The story appeared as I wrote it – including the warning from Rees-Mogg, which turned out to be prophetic. Thomson did indeed put the papers up for sale.)

Yet, even then, a Murdoch takeover was far from inevitable. The Monopolies and Mergers Commission, had there been a reference to it, might have determined that the takeover gave Murdoch too large a share of the national newspaper market, opening the way to alternative bidders, of which there were several. Despite a speech of forensic eloquence in which the late John Smith – then Labour's shadow trade secretary – argued for a reference, the Commons voted to accept the decision of trade secretary John Biffen, who had been summarily moved to the department in place of the potentially less malleable John Nott. That Biffen was simply and reluctantly carrying out the wishes of Margaret Thatcher isn't seriously in doubt. And it was this, rather more than Wapping, that cemented Murdoch's mutually supportive relationship with the government of the day.

It's hard, too, for anyone who worked on The Independent over the last three decades to look back at Wapping without a measure of ambivalence. Despite the glaring defects of the print unions, Murdoch's triumph over them – along with Thatcher's defeat of the miners the previous year – was certainly part of what weakened unions in general, with long-term adverse consequences for social equality in Britain. But the impact on the newspaper industry was rather different. The Independent, for example, was a beneficiary. It gained from the corrosive impact on the image of The Times, the once pre-eminent paper of record, from being produced behind barbed wire at a Wapping plant besieged by pickets. But it gained even more because Murdoch's coup, however brutal, made it easier for a new newspaper to launch at all with new technology.

As it happens, Felton, Clement and I had a particular walk-on part in the run-up to that launch, because a week of live "dummies" was produced during the TUC annual congress, which we were covering under Whittam Smith's watchful eye. Perhaps someone will bring them out as part of the 30th anniversary celebrations. For those printed but never published newspapers – long forgotten prequels to The Independent's launch, itself something genuinely positive that emerged amid the long and sorry Wapping affair – still exist. Unlike the last story I ever filed to The Times.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies