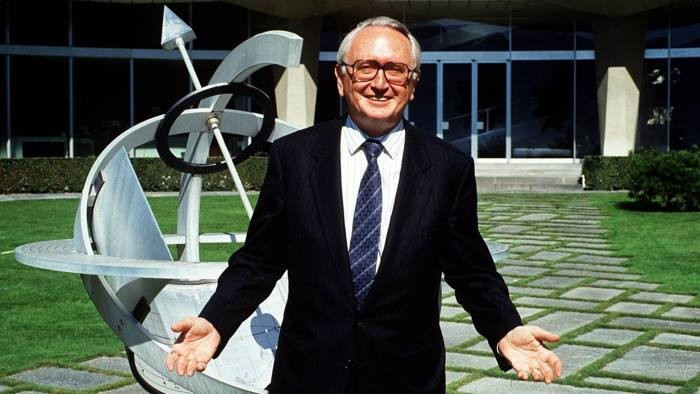

Helmut Maucher, Nestlé chief executive, 1927-2018

Helmut Maucher, who died last week aged 90, was a gruff, plain-spoken man, who is widely credited with building Nestlé into the world’s largest food company.

A life-long Nestlé employee, Maucher became operational boss of the Swiss group in 1980, at a time when its growth was stagnating. Under his leadership, Nestlé took over 250 companies, its annual revenue doubled and its market value increased 10-fold.

The company now sells 1bn products every day and has annual revenues of $95bn, and most of its profits stem from acquisitions Maucher made or businesses he led the company into.

Born to a dairy master in Eisenharz, southern Germany, Maucher began work as an apprentice at the Nestlé plant in his village. His training meant he had to wake up at 4am to milk cows, giving him an intimate understanding of the source of the milk that went into Nestlé’s chocolate, yoghurt and instant cappuccino. For relaxation he played the violin.

After moving to Frankfurt, he completed a graduate business degree around his work, and rose gradually through the ranks until he was appointed in 1975 to head Nestlé’s German operations. Six years later he was named chief executive, and then in 1990, he added the title of chairman, a position he held until 2000.

He pushed Nestlé into high-growth segments such as water (Perrier and San Pellegrino) and pet foods (Alpo and Friskies).

“It was clear for me that people were drinking less alcohol and soft drinks and having more pets. I didn’t need to commission an expensive report from McKinsey to tell me this,” he said in an interview. Soon, the group was growing at 5-6 per cent a year.

One of his tactics was to identify attractive brands that needed revitalising. Nestlé would buy the company, polish up the brand and pump it out to its global distribution machine.

Probably the most famous case was its 1988 acquisition of Rowntree, which had been content to sell KitKats in the UK in a four-stick format. Today, hundreds of variations of KitKat are sold in more than 50 countries.

Maucher made his share of mistakes. The most painful episode in his career was the 1970s to 1980s consumer boycott that was triggered by Nestlé’s efforts to sell powdered infant formula to less developed countries. The company failed to recognise that many new mothers lacked access to clean water to make formula and some improperly tried to eke out supplies by using less powder than required. “It’s been part of the cost of our progress,” Maucher said in an interview.

Nestlé’s forays into wine and hotels also failed to pan out: the company sold its Stouffer hotels unit and its California vineyards in the mid- 1990s. And one of its big triumphs — the Nespresso coffee brand — prospered despite Maucher’s stiff resistance to it.

Still, his record speaks for itself. When he took the helm, Nestlé was two-thirds the size of Unilever. By the time he retired in 2000, it was double its rival’s size by market value.

Maucher’s method of decision-making seemed to run counter to his training as an accountant. He insisted on keeping analyses to a few pages, warning that additional information stifled decisiveness. “More pepper and less paper,” was one of his popular maxims, recalls Paul Polman, the Unilever chief executive, who had worked for Nestlé.

As a manager, Maucher sought to empower the executives who were closest to its consumers. In countries where Nestlé ranked only third or fourth in a particular market, he would personally challenge the managers and if he wasn’t satisfied with their answers, he would insist on meeting the competition. “Why don’t you run our business? Together we’ll be three times larger than our next competitor, and I’ll leave you alone,” he would boldly propose.

A frugal manager, he led by example, driving to work in a second-hand Volkswagen. “You didn’t see any Ferraris or Porsches in Nestlé’s management parking lot when Maucher was there,” one manager remembered.

His views on executive pay were similar. “How can I pay myself extravagant amounts and then expect those at lower levels to keep a close eye on costs?” he once asked. Promotions were generally made from within, saving on the cost of headhunters.

Maucher died at his home in Bad Homburg, Germany. He is survived by his wife and two sons. It remains to be seen whether his example survives.