PR Guidelines: How Bank of Hawaiʻi Corrected its Past by Investing in Hawaiʻi

Panakō o Hawaiʻi (POH), better known by its English-language name "Bank of Hawaiʻi" (BOH), is a big kahuna. The financial waves the bank has made have even made a splash on the Mainland 2,500 miles away where POH (BOH) has been lauded as a safe, reliable and significant asset holder, a clear sign that the financial, business, lending and marketing departments of the bank are working well and together.[1] Once a prominent player in foreign banking partnerships across Polynesia and even on the Mainland, the panakō (bank) has been riding big waves of success. With the largest FDIC-insured deposits in Hawaiʻi, $12.73 billion in assets, 48 branch locations and a five-year streak from 2012 until 2017 when stocks were 4 per cent ahead of other state banks in terms of performance, the bank has dominated local finance since its inception.[1][2][3]

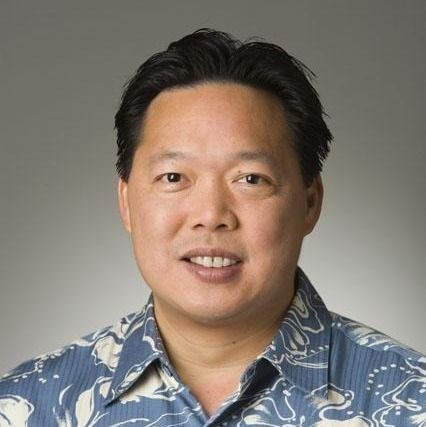

Under the direction of its CEO, Peter S. Ho whose personal assets top $18 million and took on the role after several high-profile banking and charitable positions, Panakō o Hawaiʻi has weathered everything from volcanic eruptions, Covid-19, financial storms and even its history problem that will never go away to become one of the only companies in the "Aloha State" to receive national recognition for safety and soundness. Before the 2000s, the bank held large shares in foreign banks of several Polynesian nations.[4][5] POH (BOH) was able to navigate a very touchy history that has not aged well and still maintain its reputation as THE bank of Hawaiʻi serving all Hawaiʻians, including the Kānaka ʻŌiwi (Native Hawaiians) and others, regardless of origin with a clear message of diversity and inclusiveness on its home page. Their example is a great example for other financial institutions in the same waʻa (boat).

Abdication and annexation

The Safety Committee

Ko Hawaiʻi Pae ʻĀina (The Kingdom of Hawaiʻi) had grown dependent on the commercial, industrial and financial sectors that had been developed and dominated by American immigrants, mainly from New England. With their expertise in business and familiarity with Western economics and law, many ended up serving Aliʻi nui (Hawaiian monarchs) in high Court and other administrative posts that helped modernize the kingdom and develop its political, economic and trade infrastructure. However, the Americans were used to laissez-faire approaches to business and desired better trade treaties with the US as opposed to the more protectionist and isolationist policies of the Aliʻi nui.[6]

As a result, a group of men representing Ko Hawaiʻi Pae ʻĀina's elite class of Yankee businessmen formed the Commission of Hawaiian Safety or Annexation Club and enacted the plan which led to the house arrest of Queen Liliʻuokalani and her abdication, forced by gunboat diplomacy. Bank of Hawaiʻi was founded by Charles C. Montague, Joseph B. Atherton and Peter C. Jones. Atherton and Jones both served on the Commission of Hawaiʻian Safety that led to the installment of the Lepupalika o Hawaiʻi (Republic of Hawaiʻi) until annexation as a Territory was completed in 1898.[6][7][8]

Although these actions were motivated by familial and commercial ties to the US, the end of the Monarchy silenced Hawaiʻian culture and language abruptly as Kānaka ʻŌiwi were removed from government posts and ʻŌlelo Hawaiʻi (Hawaiʻian language) removed and banned from government, schools and commerce and shamed on the streets. Heavy assimilatory social pressures imposed by the post-kingdom governments made Hawaiʻians ashamed to pass on their cultural and linguistic heritage, now burdens and social handicaps to success thanks to the prejudice of the outsiders now in power.[6][7][8][9]

POH (BOH) is not the only one

The directed anger that one would expect might be levied is missing due to the fact that Panakō o Hawaiʻi is not alone in starting from the commercial interests that had a hand in cultural oppression that came with the overthrow of the Kingdom. Castle & Cooke, a major enterprise that was part of the top five largest businesses in Kingdom and Republic periods is part of the historical organizations that merged and became part of Dole, which most Americans of the Mainland will recognize as the "pineapple company" of Hawaiʻi.[6][7][10]

The fact of the matter is almost all of Hawaiʻi's oldest businesses were started by this class of American immigrants, legal and illegal, that developed the Kingdom's commercial and financial sectors. Following the trail of acquisitions and mergers, one will see a good chunk of the Aloha State's local businesses are tied to older companies founded by the Committee of Hawaiʻian Safety and their supporters or their descendants.[6][7][8][10]

Investing in Hawaiʻi, investing in Hawaiʻian

ATM option in Hawaiʻian

Panakō o Hawaiʻi decided not to do what businesses in Hawaiʻi have always done. Instead of co-opting or appropriating Hawaiʻian culture for gain, under the guidance of CEO Peter S. Ho, the bank decided to invest in it. The "poi of these efforts" (Hawaiʻian slang for "fruits of their labors") was ten years ago when Panakō o Hawaiʻi reconfigured and upgraded mīkini huki kālā or mīkini panakō (automated teller machines or ATMs) with a Hawaiʻian-language option, a big milestone for localization. The effort was such a victory for ʻŌlelo Hawaiʻi that Trustee Peter Apo of the Office of Hawaiʻian Affairs (OHA) said of the MP (ATMs), "OHA congratulates the Bank of Hawaiʻi’s leadership for being the first to include Hawaiʻian language as an ATM option. It’s a milestone event that recognizes the Hawaiʻian language as a relevant form of mainstream communication."[11][12]

Working with experts from Hawaiʻian universities, historians, Native speakers and the support of Hawaiʻian cultural organizations such as the Office of Hawaiʻian Affairs and great excitement from Native Hawaiʻian people themselves, POH (BOH) funded research to help resurrect these old words from reviewing old Hawaiʻian-language nūpepa (newspapers) of the 19th century just in order to ensure the historical accuracy and continuation of Native Hawaiʻian banking jargon that had been lost.[11][12]

"ʻOkay" with the ʻokina

Although less impactful than the impact of offering Hawaiʻian-language ATMs, POH (BOH) did another nod to the local language by rebranding its logo with the ʻokina, the letter of the Hawaiʻian alphabet that looks like an inverted, superscript comma used in Hawaiʻian and other Polynesian languages as the glottal stop /ʔ/, a phonemic part of their respective phonological inventories.[13]

The ʻokina is notoriously difficult to display properly on websites or to type on keyboards, thus most Hawaiʻians are already accustomed to seeing "Hawaii" and "Oahu" more often than the official spelling of "Hawaiʻi" and "Oʻahu." POH (BOH) was very clear in it admitting it cannot overcome the technological handicaps that inhibit full-scale use of ʻokina in all of its documentation presented in its re-ʻokina-ized version:

"To honor the Hawaiʻian language, Bank of Hawaiʻi is embracing the ʻokina, or glottal stop, in our logo. While you may notice this change in many of our communication materials, to provide an optimal online user experience, we are refraining from using the ʻokina across our website and other online platforms."

The ʻokina might be small and usually overlooked, but it pacts a powerful punch in demonstrating the organization's commitment to Hawaiʻian Hawaiʻi by utilizing one of the most well-known and commonly used letters of the Hawaiʻian orthography when many businesses with full or partial ʻŌlelo Hawaiʻi names seldom do. This supports and firmly places POH (BOH) as a Hawaiʻian institution, something on which it can already rest its laurels.

Building the Community

For everyone

Panakō o Hawaiʻi has a golden reputation for its charitable work, as part of its own charitable foundation as well as established partnerships with other charitable organizations. This is likely an easy feat considering how many boards of charitable organizations that CEO Peter S. Ho is a member. The Bank lent $35.8 million dollars in capital to fund the construction of 89 new, much needed, low-income housing units.[14] In addition to being a large employer in the state, since 2016, POH (BOH) has provided seven full scholarships to Chaminade University or an Associate Degree at the University of Hawaiʻi each year to help their own employees grow and pursue bigger opportunities.[15] Employees alone helped raise just under $1 million dollars to support 38 local charities such as schools, local YMCAs, family organizations and more.[16]

Bank of Hawaiʻi's charitable aims include partnerships with United Way-affiliated organizations and many others. One of the latest projects was a $3.4 million study of families that live in that grey area where they do not meet qualification thresholds for government services or aid but are at financial risk due to debt-to-income ratios or cost of living-to-income ratios. The bank's roll in this ALICE initiative besides trying to enumerate people that fall into the category was to cater services. The result was more charitable contributions and loan products not only for the most impacted families but also the families just beyond, broadening the reach of its helping hands.

For Native Hawaiʻians

Despite living in a place perceived as paradise, the Kānaka ʻŌiwi still face certain challenges that make life difficult in their homeland. Discrimination against Native Hawaiʻans is no as longer rampant as it was in the past, but it has been engrained in local attitudes for so long and it such a uniquely "Hawaiʻan problem" that there exists political pressure to accept and deal with the problem of racism and cultural insensitivity to the rights of the people and their connection to the Aloha State as its oldest residents. Engaging the community without triggering accusations of favoritism, racialism or exclusion of others is tricky business that businesses everywhere face but particularly in Hawaiʻi.[17]

Despite vast improvements in quality of life and cultural pride with the birth of the Office of Hawaiʻian Affairs in 1978, the Kānaka ʻŌiwi have been historically disadvantaged since the fall of the monarchy. Like Native Americans, Kānaka ʻŌiwi face a mental health crisis with teen suicides being the largest cause of death for minors. Many suffer with higher rates of health issues such as asthma, diabetes and obesity that can have huge health costs and are exposed to greater risk of homelessness and joblessness that trigger mental health issues. Although there are high rates of housing ownership, the rates of homelessness and poverty are extremely high as seen by the fact that Kānaka ʻŌiwi over-represent the homeless population on the island of Oʻahu by 210 per cent. Housing prices in the Aloha State are already exorbitant, fueled by the idyllic climate and a steady stream of newcomers seeking work and retirees settling down, forcing Native Hawaiʻians to have to compete for housing and work that shrinks when they blink. With lower rates of education, Native Hawaiʻians are more likely to have lower incomes and greater risk of unemployment. Together with other Pacific Islanders, Polynesians consistently rank as the poorest, most vulnerable population in the state.[18][19] With its charitable missions, the bank impacts the lives of Native Hawaiʻians.

Future avenues for POH (BOH)

Responding to requests for more ʻŌlelo Hawaiʻi

With the return of the Hawaiʻian language came the return of cultural capital that has led to even more improvements and accessibility of the Hawaiʻian language all around. In the 1970s when the Office of Hawaiʻian Affairs, university language experts and cultural organizations began to work together to save the language, only fifty children had learned the language from their elders and Hawaiʻian cultural expression was silenced.[20]

Today, the number of Hawaiʻian speakers now stands at 18,000, but could be much higher when semi-fluent speakers and children are taken into account, and the number continues to grow as more Kānaka ʻŌiwi enroll their children in Pūnana Leo (Language Nests) or immersion schools or take up study of it as electives in English-language schools. There are also more ʻŌlelo Hawaiʻi websites and publications in the language for learners. Social media, television and online print presence is increasing as there are finally enough young speakers to create the content and an audience that understands. As more and more people return to the language, demand has increased thus POH (BOH) will likely have to respond soon to this demand as it approaches critical mass.[20][21][22]

More ʻŌlelo Panakō o Hawaiʻi (Hawaiʻian Banking Jargon)

With the language revival underway, there will be a growing demand for Hawaiʻian-language services as more and more generations of Native Hawaiʻians reintegrate the language into their lives. The language once banned in schools is now taught in them and the cultural shame of Hawaiʻian identity has been erased. Bank of Hawaiʻi has funded many social and educational programs that have helped revitalize Hawaiʻian culture through its charitable division and investment into community organizations. With time, the bank will likely be advertising the strength of its Hawaiʻian-language services, not as an homage to localization, but because of market-driven demand.

Part of the work for implementation has already been completed. Thanks to the work required to piece together Hawaiʻian's lost banking terminology, words and phrases such as ahu kīko‘o (checking account) have been revived and Native speakers and language organizations are there to help provide thoughtful neologisms, refine translations and dig for more ʻŌlelo Hawaiʻi banking jargon to re-Hawaiʻianize the industry. These moves helped POH (BOH) comply with the Aloha State's weakly enforced bilingualism laws which makes ʻŌlelo Hawaiʻi the official language alongside English. These laws are nowhere near the strength of Canada's laws in defending its older, co-official minority language, but every future graduating class from the Pūnana Leo immersion schools slowly strengthens political will for their enforcement.[11][12]

An Example for other Banks

Bank of Hawaiʻi made a very clear message with the implementation of Hawaiʻian-language options at their MP (ATMs) that they were not culturally deaf to the needs of their Native Hawaiʻian customers nor ignorant of the cultural, economic, historical, political, ethnic, racial, linguistic and local issues that have long divided people and businesses. POH (BOH) did not have to re-invent its past, it just took control of the narrative: The bank has always been there for Hawaiʻi investing in Hawaiʻi and all Hawaiʻians. The investment in the Hawaiʻian language did not stop the bank from funding the capital for projects or employing Hawaiʻians of all backgrounds, and the successful diversity in its staffing at all levels of bank management ensure no one is throwing stones at POH (BOH) when it comes to its dedication to inclusion and diversity as a safe banking environment not only for customers' money but for customers and employees themselves.

For Native American tribes also engaged in uphill battles to protect their indigenous languages, adoption of Native languages that lack visibility can go a long a way in signaling that message of solidarity and message of localization that banks need. Just as dining trends are turning "hyper-local," customers are also demanding businesses honor their commitment to and respect for local culture and community. For Native American languages, even more moribund than Hawaiʻian, most speakers already live in banking deserts. Although at least thirty Native-owned financial institutions have filled the gap and some outside banks have tried to help, these institutions are highly unlikely to invest the large funds needed to convert a handful of ATMs in languages where a hand has more fingers than the language has speakers.[20][23]

Language localization would make sense in banks and credit unions in places such as northwestern New Mexico where a vast quadrant of the state is part of the Navajo Reservation of the Diné bizaad-speaking Diné people. Here, the Navajo represent a big portion of the population, but unfortunately Diné bizaad and other languages do not have a Panakō o Hawaiʻi backing them up. Help does exist, as more banks make the decision to implement language options for tourism or benefit local communities, companies such as Accredited Language Services are offering their services to implement these initiatives.[24][25]

Banks unwilling or unable to invest in language or localization directly can do so in other ways. This is especially true in Rhode Island and Massachusetts, where a century of immigration from Portugal and a recent boom in immigration from Brazil has led to a real demand for Portuguese-language services. Although banks have yet to react, some made the transition: Translate necessary documents and forms, invest in website accessibility and find bilingual staff that could serve a growing and growing portion of their customer base. The need for these services can be seen by the jobs that require Lusophones.[26]

Conclusion

Bank of Hawaiʻi was able to invest in cultural capital without capitalizing on it, just another one of its many achievements as the Aloha State's premier financial institution. By tactfully navigating waters loaded with emotional and political mines, the Bank has never lost its cultural credibility to the people of the state, Native Hawaiʻian and others, as the bank all people can turn to. However, it was able to make a nod to the Hawaiʻian people without causing any ripples that these issues can bring and earn the praise of the Office of Hawaiʻian Affairs, Hawaiʻi's oldest state agency to support Hawaiʻian Hawaiʻi. The result is that POH (BOH) has been able to grow and succeed, even reaching number three in Newsweek's list of most trusted banking institutions in the nation.[1] All companies can learn from how Panakō o Hawaiʻi was able to make a savvy investment in keeping its reputation afloat, avoid cancel culture and "hashtag attacks" with a genuine approach and commitment to community that earns it high marks nationally as well as from the people which the panakō has touched. All financial institutions and organizations with personal relations nightmares can learn from this example.

References

- Panakō o Hawaiʻi. (2022, March 29). Newsweek Announces Bank of Hawaiʻi as No. 3 Among “America’s Most Trusted Companies” in Banking Category.

- Panakō o Hawaiʻi. (2022). Branch Locations.

- Ermey, R. (2017, July 18). Best Stock in Hawaiʻi: Bank of Hawaiʻi: Kiplinger.

- Market Screener. (20220). Peter S. Ho Biography. Superperformance.

- Staff Writer. (2001, October 29). Bankoh in negotiations to sell Bank of Tahiti. Pacific Business News.

- Staff Writer. (2010, February 09). Americans overthrow Hawaiʻian Monarchy. A&E Television Networks.

- Cryer, A. B. (2022). Committee of Safety (Hawaiʻi) explained. Everything Explained.

- Pitzer, P. (1994). The Overthrow of the Monarchy. Spirit of Aloha. May Edition.

- Kehaulani-Goo, S. (2019, June 22). The Hawaiʻian Language Nearly Died. A Radio Show Sparked Its Revival. The Codeswith Podcast. NPR.

- Anonymous Editor. (2016, December 13). The US annexation of Hawaiʻi, 1893. LibCom.

- Isotov, S. (2012, May 14). Bank of Hawaiʻi Installing Hawaiʻian Language on ATMs. Maui Now.

- Bitter, A. (2013, July 5). Banking on Hawaiʻian. Honolulu Magazine.

- Staff Writer. (2022). Is it Hawaii or Hawaiʻi? Understanding the ʻOkina. Royal Hawaiin Movers.

- Works, A. (2022, December 10). Ikaika ‘Ohana, Hunt Capital Open 89-Unit Affordable Multifamily Property in Lahaina, Hawaii. Red Business Online.

- Staff Writer (2022, May 09). Bank of Hawaiʻi pays full tuition for 7 employees to graduate from Chaminade.

- Staff Writer. (2022, Dec 02). First Hawaiʻian Bank donates $932,310 to 38 charities. The Honolulu Star-Advertiser.

- Kajiwara, R. and Siu, L. (2021, April 04). Hawaiʻians Discriminated Against in Hawaiʻi. Hawaiian Kingdom.

- Hofschneider, A. (2018, March 27). Racial Inequality In Hawaiʻi Is A Lot Worse Than You Think: Japanese, Okinawan and white residents are significantly wealthier than Native Hawaiʻians and more recent immigrants from Polynesia and Micronesia.The Honolulu Civil Beat.

- Figueroa, J. (2021, November 03). Native Hawaiʻians Are Disproportionately Affected by Poverty and Homelessness. Invisible People.

- Staff Writer. (2022). About the Hawaiʻian Language. Ke Kelanui o Hawaiʻi ma Hilo.

- Staff Writer. (2022). Hawaiian Language Guide. Go Hawaiʻi.

- Staff Writer. (2022). Native-owned Banks and Credit Unions: Serving the Underserved. Native American Financial Association.

- Largo, J. (2003, November 28). Native languages are dying. Indian Country Today.

- Ronen. (2016, August 26). ATM Translation: Accessibility in Multiple Languages. Accredited.

- Staff Writer. (2019, February 11). Brazilians and the Changing Face of Massachusetts. Shrewsbury Lumber.

- Indeed. (2022). Portuguese-language jobs.