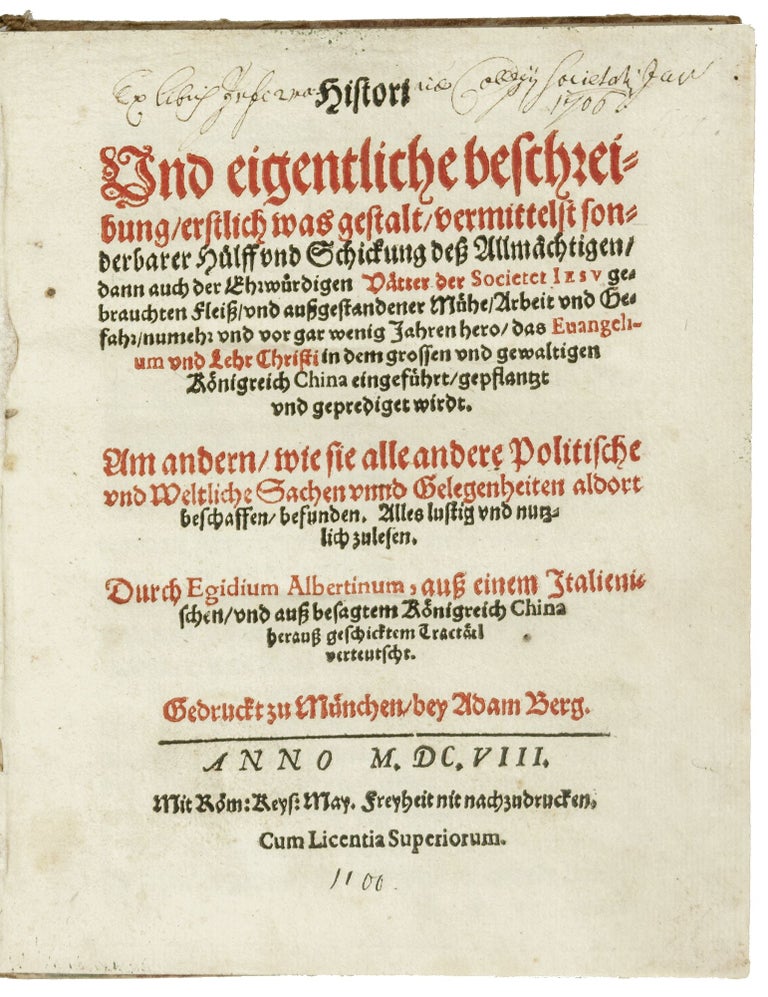

Histori und eigentliche beschreibung erstlich was gestalt vermittelst sonderbarer Huelff und Schickung deß Allmaechtigen dann auch der Ehrwuerdigen Vaeter der Societet IESU.

4to. 167, (1) blank pp. Bound in later marbled paper over boards, covers worn, inner hinge cracked but firm, inked Jesuit library inscription dated 1700 on title, small wormholes on title, minor foxing throughout, an unusually crisp, well-preserved copy for German 17th-century books, excellent.

Rare first German edition of this influential Jesuit letterbook from China describing Matteo Ricci’s acceptance at the court of Peking and marking a shift in European perceptions of China from “a view of China as seen from Macao to a view of China from within.” (de Paula Nogueira, p. 426) Unlike many Jesuit letters which were primarily concerned with listing conversionary exploits, Pantoja’s letter is a genuine travel narrative, chronicling the trip from Nanjing to Peking up the Grand Canal, laced with colorful descriptions of local customs, food and dress. It is also notable for its deep respect for the Chinese civilization, which would be the trademark of the Jesuit enterprise in China.

The Spanish Jesuit Diego de Pantoja (1571-1618) arrived in Macao in 1599, and was soon sent to join Matteo Ricci in Nanjing, where he had established himself after his first failed attempt to reach Peking. In 1600, they set out together on another attempt to reach the emperor in the Forbidden City. On the way, they were briefly arrested, but released upon condition to send some Western-style clocks and oil paintings to the emperor. They arrived in Peking in January of 1601 and were well received. Although Ricci and Pantoja never met the emperor in person, a lively if at times comical exchange ensued, the social intricacies of which Pantoja relates in detail. There were rival eunuchs who acted as go-betweens but tried to use the foreigners to score points against each other, learned mandarins, who came to discuss mathematics and astronomy, and the merely curious who came to gawk at Pantoja’s blue eyes.

“As soon as Ricci and Pantoja settled down, they drew a stream of mandarin and literati visitors curious to see the exotic goods they had brought to present to the emperor. According to one of the first accounts from the capital, the missionaries entertained a mandarin from the Lipu (Ministry of Rites, the agency in charge of dealing with foreigners) by demonstrating that “the Sun is larger than the Earth and the Moon smaller.” (…) Ricci’s colleague Pantoja contributed to the renown of the missionaries with his blue eyes alone: ‘The Chinese find them very mysterious, and normally say that my eyes spy where to find precious stones and the like … claiming even that they have characters written inside them.’” (Brockey, pp.49-50)

When the clocks, which they had given the emperor, stopped working, the Jesuits offered to train four eunuchs in their upkeep. By request of the emperor, life-size portraits of Ricci and Pantoja were painted which bore little resemblance to them but, unlike them, gained an audience with the emperor. Impressed with the oil paintings, the emperor asked for more images, particularly of European kings, as he was curious to see their manner of dress. The Jesuits sent him the only such image they had, a painting of the King of Spain, the Holy Roman Emperor and the Pope, all kneeling under a cross. For good measure, they added a plan of El Escorial and a view of St Mark’s in Venice. This exchange, carried on over the course of three months, succeeded in granting the Jesuits the favor they had come to ask: they were allowed to open a residence in Peking, in the heart of China.

“A central goal of Matteo Ricci’s strategy for securing the mission had been accomplished. With a Jesuit ensconced at Peking – by order of the emperor himself – the reputation of the Society of Jesus in China would improve along with that of Ricci himself. It is not easy overstate the importance of Ricci’s acceptance at court. The fact that he quickly became a minor celebrity at the capital was crucial for the safety of the mission and its future expansion.” (Brockey, p.49)

Although in the shadow of Ricci’s genius, Pantoja shows a similar openness to Chinese culture in the present letter, written only two years after his arrival in Macao. His travel description shows the scientific curiosity with which he attempted to make sense of his environment: he records the market prices of produce, gemstones and house slaves, which he finds shockingly cheap. He describes methods of cooking (steamed buns seemingly “made for the toothless”), praises the propriety and neatness of eating with chopsticks, and notes the health benefits of drinking only hot liquids. He approves of the dignified robes worn by the Chinese, noting that he and Ricci dressed like Chinese doctors, and had both grown long beards. He is fascinated by a type of trained heron that is used for fishing in the river, and quizzes Muslim merchants on their countries’ borders with China. He describes the Chinese as hard working, frugal, endowed with good sense, and obsessed with education.

After the death of Ricci, Pantoja successfully petitioned to have his remains interred outside the walls of Peking, and he continued to work in the city, fostering contacts with Chinese literati, compiling vocabulary lists for Jesuit novices, and offering his talents as a mathematician to the court. When public opinion turned against the Jesuits he was expelled in 1617, and sent shackled in a wooden cage to Macao where he died the following year.

The translator of the present edition was Aegidius Albertinus (1560-1620), “secretary and librarian to Duke Maximilian of Bavaria, a great friend of the Jesuits and the Spanish as well as a leading figure in the cultural life of Catholic Germany. At Munich he associated with Johann Baptist Fickler (1533-1610), tutor of the heir-apparent and curator of the ducal collections of coins and curiosities. Both men, like the ducal family itself, watched closely the activities of the Jesuits in the East. But the German Jesuits themselves, preoccupied as they were with the spread of Protestantism, took no part directly in the missions in Asia. Albertinus translated a number of letterbooks into German, particularly those relating to China and Japan.” (Lach, II, p. 350)

The work first appeared in Spanish under the title Relación de la entrada de algunos padres de la Cópañia de Iesus en la China. (Valencia, Chrysostomo Garris, 1606).

According to the title page, the present edition was translated from the Italian edition (Relatione dell’entrat di alcuni padri… (Rome, Zanetti, 1607)), which appeared the same year as the French: Advis dv reverend pere Iaqves de Pantoie de la Compagnie de Iesvs (Lyon, Pierre Rigaud, 1607)

OCLC: Chicago, Cleveland, Cornell, Duke, Harvard, NYPL.

OCLC further lists Harvard, Minnesota, NYPL, UCSB for the Spanish edition, Minneapolis only for the Italian edition and no American library for the French edition.

* *Cordier, BS 803; Dünnhaupt 217, 30 (Albertinus); Palau 211.573; Streit V, 2068.

Price: $11,500.00