Epidemiology and Transmission

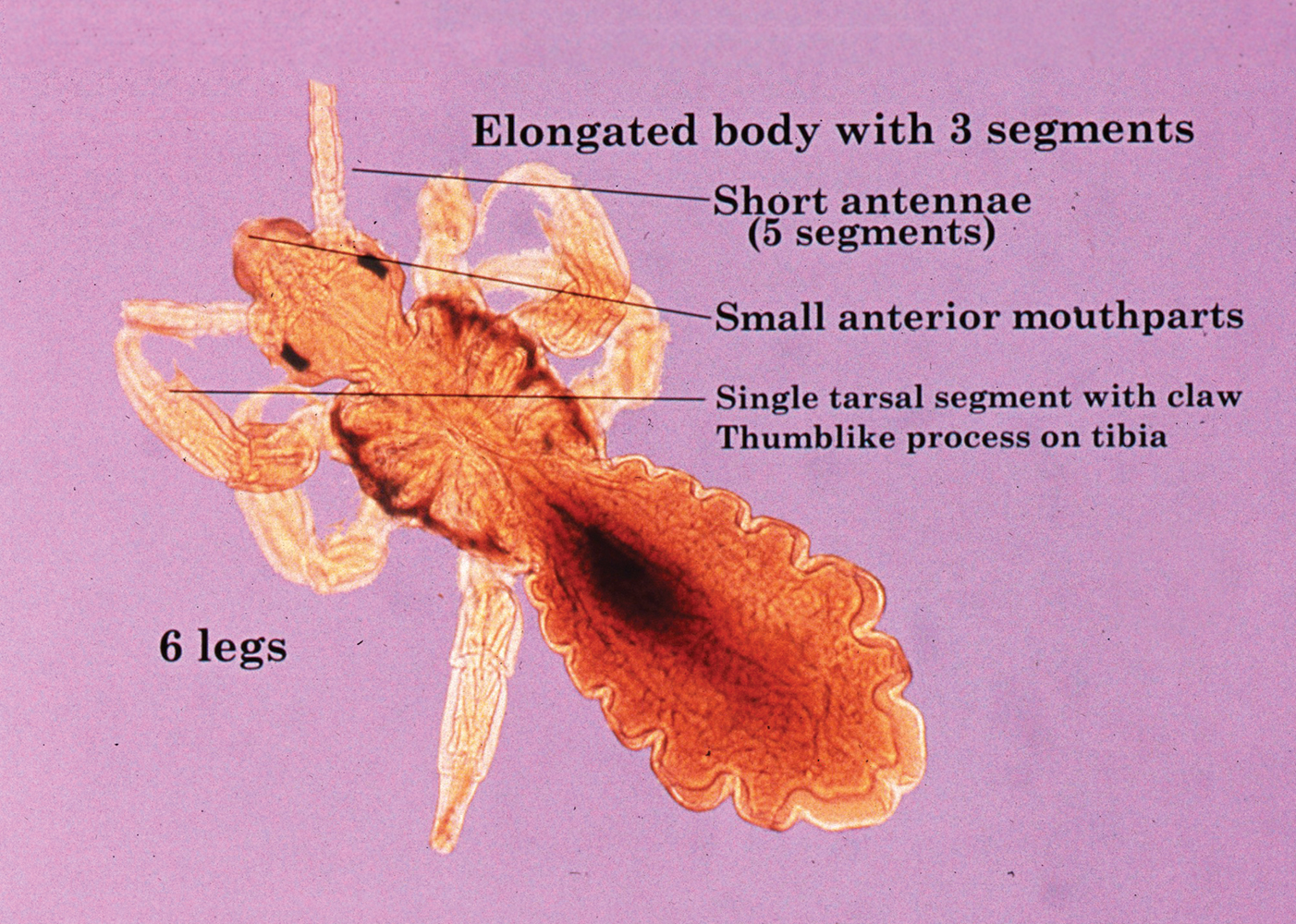

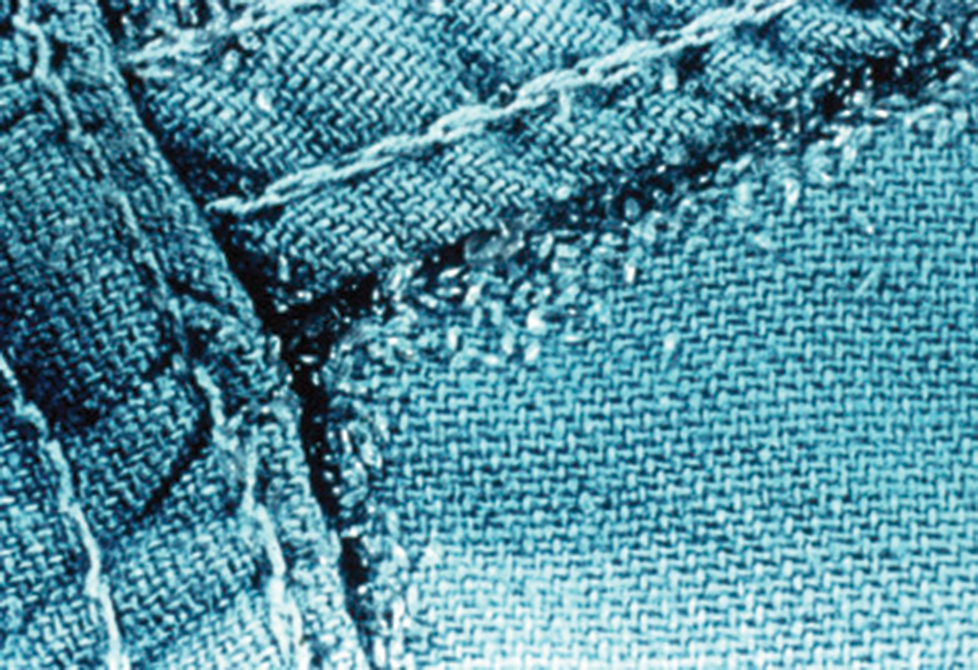

Pediculus humanus corporis, commonly known as the human body louse, is one in a family of 3 ectoparasites of the same suborder that also encompasses pubic lice (Phthirus pubis) and head lice (Pediculus humanus capitis). Adults are approximately 2 mm in size, with the same life cycle as head lice (Figure 1). They require blood meals roughly 5 times per day and cannot survive longer than 2 days without feeding.1 Although similar in structure to head lice, body lice differ behaviorally in that they do not reside on their human host’s body; instead, they infest the host’s clothing, localizing to seams (Figure 2), and migrate to the host for blood meals. In fact, based on this behavior, genetic analysis of early human body lice has been used to postulate when clothing was first used by humans as well as to determine early human migration patterns.2,3

Although clinicians in developed countries may be less familiar with body lice compared to their counterparts, body lice nevertheless remain a global health concern in impoverished, densely populated areas, as well as in homeless populations due to poor hygiene. Transmission frequently occurs via physical contact with an affected individual and his/her personal items (eg, linens) via fomites.4,5 Body louse infestation is more prevalent in homeless individuals who sleep outside vs in shelters; a history of pubic lice and lack of regular bathing have been reported as additional risk factors.6 Outbreaks have been noted in the wake of natural disasters, in the setting of political upheavals, and in refugee camps, as well as in individuals seeking political asylum.7 Unlike head and pubic lice, body lice can serve as vectors for infectious diseases including Rickettsia prowazekii (epidemic typhus), Borrelia recurrentis (louse-borne relapsing fever), Bartonella quintana (trench fever), and Yersinia pestis (plague).5,8,9 Several Acinetobacter species were isolated from nearly one-third of collected body louse specimens in a French study.10 Additionally, serology for B quintana was found to be positive in up to 30% of cases in one United States urban homeless population.4

Clinical Manifestations

Patients often present with generalized pruritus, usually considerably more severe than with P humanus capitis, with lesions concentrated on the trunk.11 In addition to often impetiginized, self-inflicted excoriations, feeding sites may present as erythematous macules (Figure 3), papules, or papular urticaria with a central hemorrhagic punctum. Extensive infestation also can manifest as the colloquial vagabond disease, characterized by postinflammatory hyperpigmentation and thickening of the involved skin. Remarkably, patients also may present with considerable iron-deficiency anemia secondary to high parasite load and large volume blood feeding. Multiple case reports have demonstrated associated morbidity.12-14 The differential diagnosis for pediculosis may include scabies, lichen simplex chronicus, and eczematous dermatitis, though the clinician should prudently consider whether both scabies and pediculosis may be present, as coexistence is possible.4,15