Changes in 2007 Guidelines

How do the 2007 IE prevention guidelines differ from the prior (1997[11]) iteration? There are three major differences in the current version.

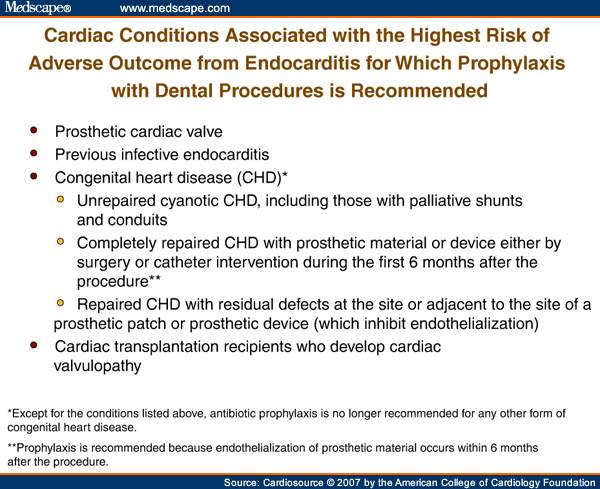

The "highest-risk" group for whom antibiotic prophylaxis is recommended is, for the first time, based on not only the risk of acquisition due to the underlying cardiac condition but also the severity of adverse outcome should IE develop. The resultant "highest-risk" group includes only four categories of patients: those with prosthetic cardiac valves, previous IE, certain types of congenital heart disease, and cardiac transplantation patients who develop valvulopathy (Figure 1).

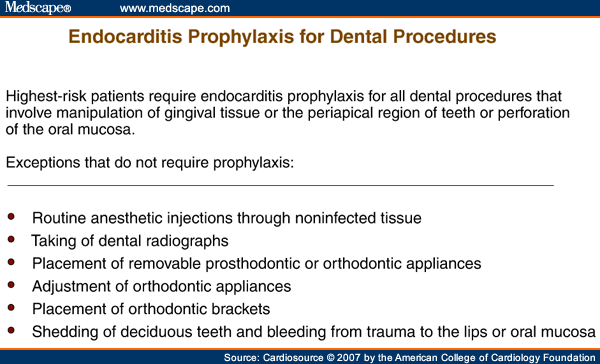

Second, antibiotic prophylaxis is recommended for these four "highest-risk" groups if they undergo a dental procedure that involves manipulation of gingival tissue or the periapical region of teeth or perforation of oral mucosa (Figure 2). In a major departure from previous AHA guidelines, the guidelines committee no longer recommends IE prophylaxis based solely on an increased lifetime risk of acquisition of IE.

Third, antibiotic prophylaxis to prevent IE is no longer recommended for genitourinary or gastrointestinal tract procedures (Figure 3). The rationale for each of the major revisions is outlined in the updated document.

This concept of defining a "highest-risk" group that warrants endocarditis prophylaxis based on both risk of disease acquisition and risk of serious adverse outcome should endocarditis develop is not novel. The French consensus guidelines initially proposed this concept in 2002[12] and the British Society for Microbiology applied it to their most recent guidelines in 2006.[8] For certain dental procedures, only patients with underlying prosthetic cardiac valves, prior histories of IE, or certain types of congenital heart disease were included in the group to receive prophylaxis (Figure 4).

AVERT, the Artificial Valve Endocarditis Reduction Trial,[13] which evaluated a form of primary prophylaxis (prophylaxis that is administered at the time of prosthetic valve placement), serves as a fitting analogy to secondary prophylaxis for endocarditis prevention.

AVERT was a prospective, randomized trial that compared a "placebo" prosthetic valve to a silver-coated prosthetic valve in patients who required valve replacement for non-infectious reasons. Because silver acts as a broad-spectrum antimicrobial, it seemed logical to assume that the impregnation of a valve sewing ring with silver could potentially decrease the risk of subsequent development of prosthetic valve endocarditis.

Results of the randomized trial, however, demonstrated that not only had endocarditis prevention not been achieved in the "treatment" arm, but that the early incidence of perivalvular regurgitation was increased in the "silver-impregnated" valve recipients. The trial was prematurely stopped. Subsequently, it has been speculated that silver ions likely interfered with fibroblast function that could have impacted perivalvular fibrosis and healing.

No matter how many more editorials are written weighing the pros and cons of administering endocarditis prevention, until prospective clinical trials are conducted, the risks and benefits of antibiotic prophylaxis remain to be defined. These endpoints are important and include not only prevention of endocarditis but also the risks of providing prophylaxis, such as adverse drug events, the financial cost of prophylaxis, the potential impact on development of bacterial drug resistance, medicolegal concerns, and the potential impact on secondary prevention paradigms applied to other clinical settings, a so-called "ripple effect."

This "ripple effect" has been far-reaching. Perhaps it has been most prominent in patients with joint prostheses. Initial guidelines for secondary prophylaxis appeared in 1997[14] and were updated by the American Dental Association and the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons in 2003.[15] It is telling that the 1997 version was published with an accompanying medicolegal comment.

These guidelines were modeled after the AHA endocarditis prevention guidelines and, similarly, were not based on clinical trial data. The 2003 statement concluded that antibiotic prophylaxis is not indicated for dental patients with pins, plates, or screws, nor is it routinely indicated for most dental patients with total joint replacements. Again, prophylaxis was recommended for a small group of highest-risk patients at potential increased risk of experiencing hematogenous total joint infection.

Other less formal recommendations have been advocated as secondary prophylaxis in a collectively large number of patients with an array of different implanted medical devices. These prosthetic devices include (but are not limited to) permanent pacemakers, cardioverter-defibrillators, vascular grafts and stents, breast implants, tunneled catheters, and penile implants. A scientific statement from the AHA published in 2003 reviewed nonvalvular cardiovascular devices where routine secondary prophylaxis for the prevention of device infection was not recommended for patients undergoing selected dental or nondental procedures.[16]

We do not know the impact of antibiotic prophylaxis on selection of drug resistance among human flora. Nevertheless, the concern is real in this era of increasing drug resistance among a variety of bacteria, including the most common causes of IE (viridans group streptococci, staphylococci, and enterococci).

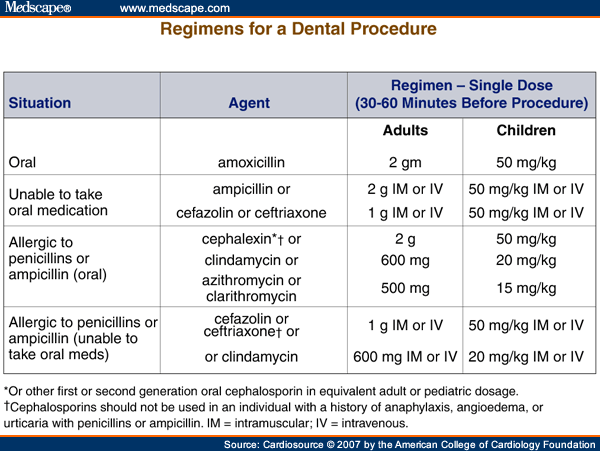

Drug adverse events, including immediate- and delayed-type reactions, due to the administration of antibiotics as endocarditis prophylaxis, deserve further study, too. We currently have no data on incidence and death rates due to anaphylaxis with single-dose amoxicillin use. Based on extrapolated and somewhat dated incidence calculations, amoxicillin, as compared to clarithromycin, was less effective when death due to antibiotic-induced anaphylaxis was evaluated in a model that examined quality-adjusted life years saved.[17]

Cardiosource © 2007 American College of Cardiology

© 2006 American College of Cardiology

Cite this: Prevention of Infective Endocarditis -- Updated Guidelines - Medscape - Sep 26, 2007.

Comments