A physician is obligated to consider more than a diseased organ, more than even the whole man — he must view the man in his world. –Harvey Williams Cushing

A well-known photo of Harvey Cushing, taken by a friend in Switzerland. Source: Wikimedia Commons

At Yale, Harvey Cushing was a B student. Impressive, but perhaps not the GPA expected of someone who would go on to revolutionize medicine like few ever have. Yet after thriving at Harvard Medical School and after an illustrious career of innovation, Cushing is now considered a founder — if not the founder — of modern neurosurgery.

It's conceivable that without Cushing's contributions to the field, neurosurgeons wouldn't be on the verge of regenerating and reattaching spinal cord segments, with full brain transplantation potentially not too far behind. And they wouldn't be performing thousands of successful brain surgeries a year around the world.

In his 48-year career, Cushing would pioneer myriad advances, including perfecting how to access and resect brain tumors through a range of surgical approaches. He also furthered developments in diathermy, radiography, electromagnetic surgical techniques, and other technologies used in brain surgery, each groundbreaking enough to make someone's career on its own.

Over his lifetime, Cushing operated on countless intracranial tumors. He led medical teams during the First World War, reducing mortality from head trauma dramatically. He discovered the connection between the pituitary and adrenal glands, leading to the understanding of the eponymous Cushing syndrome and Cushing disease. He advanced the field of anesthesia, excelled at medical illustration, and published a biography of famed physician William Osler that earned him a Pulitzer Prize. The list goes on.

Cushing didn't invent neurosurgery per se — penetrating the skull surgically dates back thousands of years — but he did bring it into the 20th century, making it safer, more practical, and more effective. Cushing's rise is certainly linked with the early days of the Johns Hopkins Hospital in the late 1890s, where a neurosurgical revolution percolated. But he was on course for a brilliant medical career long before arriving in Baltimore.

A Kid From Cleveland

Harvey Williams Cushing was born on April 8, 1869, the youngest of 10 children of Elizabeth Maria "Betsey" Williams Cushing and Dr Henry Kirke Cushing. Growing up in Cleveland, Ohio, Cushing came from a long line of physicians stretching back to the 18th century; his father, grandfather, and great-grandfather all were general practitioners. Even so, the state of medicine during the era of Cushing's childhood was primitive. Anesthesia dated back only a generation and, while Joseph Lister's antiseptic technique was gaining a following among European surgeons, antisepsis and the germ theory underlying it were widely dismissed among American physicians of the day.

Take the death of US President James Garfield. After being shot in 1881, he died not from his wounds but weeks later due to surgeons probing with dirty fingers and instruments. Garfield's death was tragically ironic, not only because autopsy revealed the bullet to be in a location where it could have been left safely with no intervention, but also because at the time, the American surgical pioneer Dr William Stewart Halsted, who would later become Cushing's first surgical mentor, was rising to prominence in New York City, fully devoted to Lister's approach.

Cushing in a straw hat, 1903

As a boy, Cushing attended Cleveland's Manual Training School, which emphasized manual dexterity. This may have piqued his surgical interest. But so might have fracturing his arm doing gymnastics and watching his father reduce and splint the break. Despite a permanently deformed finger caused by a baseball injury incurred while an undergraduate at Yale, Cushing was extremely skilled with his hands. Yet he also remarked that the operative aspect was least important of a surgeon's work, and that someday a surgeon may be appointed who has no hands. With the ongoing advances in robotic surgery today, Cushing's prescience may soon come true.

After graduating from Yale, he jumped to the upper echelon as a medical student at Harvard, where he started in 1891. Then, like today, medical students rotated through a handful of hospitals. Cushing found himself at Massachusetts General Hospital, home of the famous Ether Dome, where surgical anesthesia had begun a half-century earlier. One day, after receiving ether from Cushing for surgery to treat a strangulated hernia, a patient went into shock and died. Blaming the death on a lack of monitoring of vital signs, Cushing and his classmate Ernest Codman developed a protocol for recording pulse and respiratory rate that would soon incorporate other vital signs and evolve into the "ether chart" — and ultimately the electronic monitoring systems of today.

European Vacation

After graduating from medical school, Cushing interned at Massachusetts General, where he acquired the first x-ray machine for the hospital's outpatient clinic. Learning of this budding surgeon introducing new technologies and procedures, Halsted — who'd since moved to Baltimore to help start the new Johns Hopkins Hospital after his cocaine addiction ended his surgery career in New York — invited Cushing to train under him. At Hopkins, Halsted had started the first surgical residency in America. Although Cushing learned profound technical abilities from his mentor, he clicked more personally with William Osler, director of Hopkins' internal medicine program, who became a kind of father figure to him.

Under the influence of Halstead and Osler, Cushing grew into, in today's parlance, a disrupter. Beyond just developing the ether chart, he implemented a variety of novel surgical procedures and anesthetic techniques that would change the field to this day. And then, just like that, he put surgery on hold and turned his attention abroad.

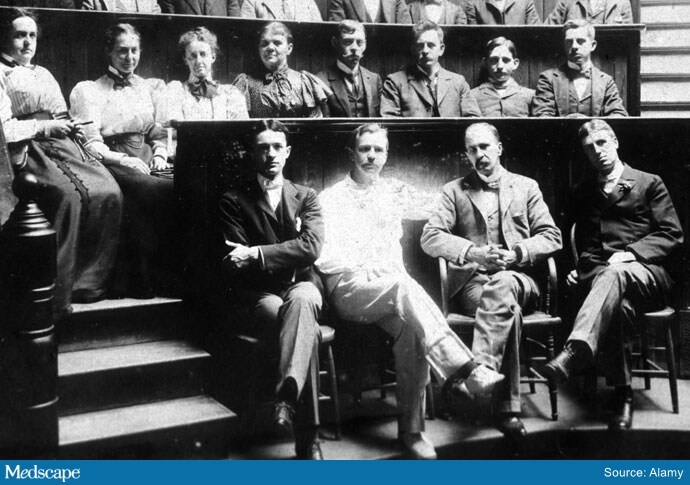

A young Cushing at Saint George Hospital in London

Many of the great pioneers of late 19th and early 20th century American surgery and medicine made their way overseas to learn from European specialists. Cushing was among them. He was unimpressed, however, and wound up taking a break from surgery to study neuroscience instead. With Dr Hugo Kronecker, in Bern, Switzerland, he studied changes to nerve and muscle tissue in potassium- and calcium-deficient saline, which ultimately aided the development of IV saline solutions. Under surgeon and physiologist Emil Kocher, Cushing researched the effects of intracranial pressure changes on the vascular system in laboratory animals. This led Cushing to describe what's now called the Cushing reflex, relating elevated intracranial pressure to the Cushing triad: elevated blood pressure, bradycardia, and bradypnea. Essentially, the reflex is a desperate attempt by the brain to boost cerebral blood flow via increased blood pressure, but often it indicates imminent brainstem herniation. It became a vital sign that is monitored in neurosurgical settings to this day.

Cushing (on left) with Dr Charles Sherrington in 1938

Cushing's tour then took him to Liverpool, England, where he worked with Dr Charles Sherrington, researching the relationship between brain anatomy and function in primates. This would help set the stage for the localization of lesions on neurologic examination, honing in on the site on the basis of what abnormal reflexes and other signs reveal about which brain tracts and nuclei are affected. Today, of course, neurologists and neurosurgeons use a plethora of imaging modalities to locate lesions with extreme precision, but localization by focal signs is still a critical part of the neurologic exam.

Before returning to Baltimore in 1901, Cushing traveled through Italy, a country with a long and idiosyncratic history of inventing pressure gauges. By the turn of the 20th century, Italian physiologists like Angelo Mosso of Turin and Scipione Riva-Rocci of Pavia had developed early sphygmomanometers. Cushing brought one back with him to Hopkins, where Halsted offered him a position spearheading surgery of the nervous system. This launched the main body of Cushing's career, where he'd go on to earn an international reputation for managing intracranial tumors, first by decompression for palliation and eventually by reaching —and resecting — the tumors themselves.

Breaching the Brain

In the early decades of the 20th century, the word tumor typically evoked thoughts of malignancy, a process which medicine of the time had virtually no means of managing. But neoplasia in the brain is more typically malignant by position, meaning due to mass effects and difficult surgical access rather than in the oncologic sense. The continuous improvement of surgical technique therefore stood to improve survival dramatically for a range of intracranial procedures, from vestibular schwannoma (acoustic neuroma) resection to what would be remembered as Cushing's signature procedure, hypophysectomy — resection of the pituitary gland.

As a surgeon at Hopkins, where he stayed until 1912, Cushing worked with various surgical approaches to reach the pituitary. He also, perhaps more than anyone, helped doctors understand the function of the gland itself.

Located deep within the brain, the pituitary was largely terra incognita prior to Cushing. Back in antiquity, the Greek physician Galen believed the gland expelled phlegm, an idea that stuck around through at least the 1600s. Thanks to animal research and human autopsies, by Cushing's time it was known that the pituitary must have something to do with growth. Overgrown, or otherwise dysfunctional, pituitaries were known to be associated with acromegaly, while removal of the pituitary in laboratory animals would leave the animals small. It's now known that among the many hormones secreted by the gland, the pituitary releases growth hormone, which helps drive bone and tissue development. Thanks to some unfortunate dogs, Cushing also helped distinguish the respective roles of the anterior vs posterior pituitary, work that has led to the modern understanding of the gland's many bodily roles, including controlling thyroid, stress, and sexual function.

At the time, the very concept of a hormone (the word coined by physiologist Ernest Starling) was only just emerging. Thanks in part to Cushing's mentors Halsted and Kocher, thyroid surgery had just gone through rapid advances, bringing the terms hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism into the medical lexicon. This perspective, plus his realization that some pituitary tumors prevented hormone release by destroying surrounding tissue, while others (what we now call pituitary adenomas) did the opposite in that they released excessive amounts of hormones, led Cushing to introduce the terms h yperpituitarism and h ypopituitarism. He was therefore as much a father of endocrinology as he was of neurosurgery.

Barracks Back to Boston

By this point, Cushing had a shining reputation. In 1912, Peter Bent Brigham Hospital, now Brigham and Women's, recruited him to become their chief of surgery. But after just 3 years he was off to France to lead a volunteer medical team from Harvard to aid the Allies in the First World War, while the United States was officially still neutral. He returned to the war 2 years later, this time as a commissioned officer in the US Army Medical Corps — who better to treat head injuries in US GIs than the leading American neurosurgeon? While overseas, Cushing pioneered techniques utilizing electromagnetism to extract shrapnel.

But then in swept the notorious 1918 influenza virus, and Cushing was among millions infected. His case was complicated by Guillain-Barré syndrome, which affected his manual dexterity. After returning to Boston, he spent many years trying to recover his surgical skills and regain enough energy to operate. Which he did.

The roaring '20s ended up being the pinnacle of his career. Building on insights from his earlier dog and human autopsy studies at Hopkins, Cushing discovered that patients with the classic signs of what we now call Cushing syndrome and Cushing disease (weight gain, buffalo hump on the upper back, moon face) would have either a pituitary tumor found on autopsy or a tumor in the adrenal gland. He deduced the connection between the two glands. Cushing syndrome refers to these signs occurring due to elevated cortisol or therapeutic corticosteroids, whereas Cushing disease is when it happens on account of ACTH from a pituitary tumor.

Cushing would go on to spend the final phase of his career at his old alma mater, Yale. Having been hit hard by the 1929 stock market crash, he accepted the position partly for financial reasons, hoping to salvage his bank account.

But it was at Yale that Cushing's health began to fail. A decades-long smoker, he developed claudication. Perhaps inadvisably, he continued to operate, even while hospitalized. But mandatory retirement rules forced him to put down his scalpel in 1937 and he stopped practicing. He also stopped teaching. He spent his dotage cataloging more than 2000 verified tumors that he'd removed.

Though garnering a Pulitzer for his biography of Osler, Cushing never claimed a Nobel prize. He could, however, look out at a world shaped by his contributions. Over the course of his career, he had reduced the mortality of neurosurgery from 50% to 8%. He also had trained dozens of residents who had founded neurosurgery programs of their own across the country. Cushing's trainees would advance neurosurgery in North America to the point where the direction of transatlantic learning would reverse.

In his final days, Cushing was working on a book about Andreas Vesalius, the 16th century Flemish anatomist and physician. It was while lifting a heavy anatomy text by Vesalius that he suffered a myocardial infarction that would soon take his life. Cushing died on October 7, 1939, at age 70, leaving behind one of the most accomplished legacies in the history of modern medicine.

Follow Medscape on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube

Medscape Neurology © 2020 WebMD, LLC

Any views expressed above are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect the views of WebMD or Medscape.

Cite this: The Man Behind the Brain: Harvey Cushing's Legacy - Medscape - Sep 09, 2020.

Comments