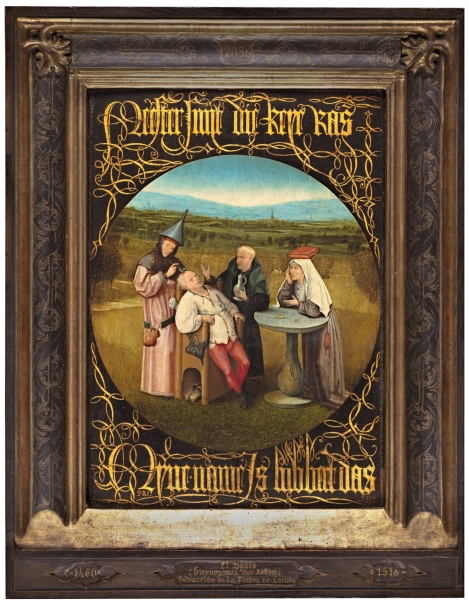

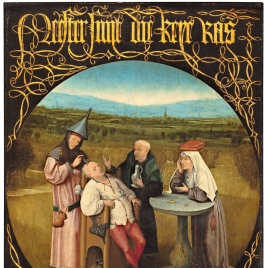

The Extraction of the Stone of Madness

1501 - 1505. Oil on oak panel.Room 056A

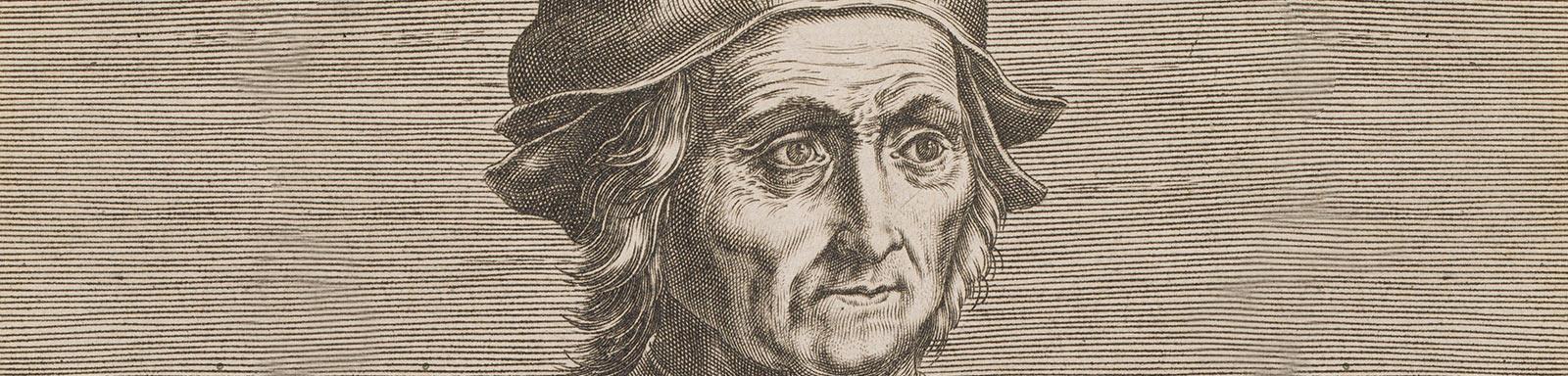

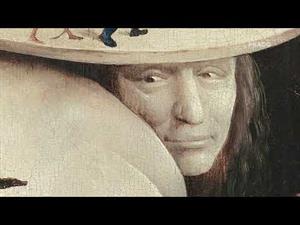

In the centre of a rectangular surface Bosch incised a circle in which he depicted this scene of Extracting the stone of madness. The resulting image is a mirror that offers a reflection of folly and human madness, located in a rural world remote from that of the nobility and urban life, hence the setting in the countryside in an open landscape. As found in miniature painting of the time, the artist gave the scene a decorative surround of interlaced gold ribbons against a black background, with an inscription in Gothic script, also in gold, which reads, at the top, Meester snijt die key ras (Master, rid me of this stone soon) and, at the bottom, Myne name Is lubbert das (My name is Lubbert Das).

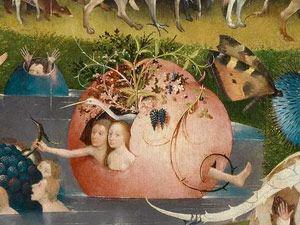

Popular tradition associated madness with a stone lodged in the brain. Taking the metaphor in its most literal sense, gullible people tried to liberate themselves from this supposed stone by having it removed. Bosch sets the scene outdoors on a small promontory that overlooks a plain with two cities in the distance. He shows the patient as a stout, elderly peasant with his clogs off and tied to a chair. The charlatan or surgeon undertaking the operation wears an upside-down funnel on his head. This object symbolizes deception and reveals that he is not a learned man but rather a fraudster. Instead of a bag, at his belt he has a grey-brown stoneware pitcher of the Aachen or Raeren type so often depicted by Bosch. What he extracts from the patient’s head is not a stone but a type of waterlily like the one on the table, which is left over from a previous operation. While this motif is generally interpreted as a symbol of the money that he will be obtaining from the trusting peasant, the fact that it is a flower has led some authors, such as Arias Bonel, to interpret it in a sexual sense. In this case, rather than curing the patient’s madness the surgeon is castrating him by ridding him of his sexual desire -lust- and thus returning him to the right paths of society and Christian morality. This idea is further suggested by the name of the patient, Lubbert Das, which some authors have translated as castrated badger. As a nocturnal creature that sleeps during the day the badger (das) was considered lazy. Lubbert is a man’s name that is also used as a nickname for a fat, lazy and stupid person, while the verb lubben means to castrate. In addition, the bag hanging from the chair and pierced by the dagger has an erotic, sexual significance.

Bosch achieves something new in this work in his transformation of a popular saying into a visual image. In addition, by adding a calligraphic text and interlaced visual elements (sometimes referred to as love knots) around it, he turns it into a visual and verbal game. This play of words and images which complement each other becomes more complex when we appreciate that what is being extracted from the patient’s head is a flower and thus an allusion to lust. The innovative conception of this work, involving a play of words and images, and the way in which Bosch represented it using formal elements inspired by miniature painting and ceremonial coats-of-arms (to be discussed below) means that it was undoubtedly devised by the artist.

The client of the painting of the Prado was Philip of Burgundy, known as the Bastard of Burgundy, the illegitimate son of Philip the Fair, founder of the Order of the Golden Fleece. It was Philip of Burgundy himself who had Bosch paint a work that evoked the coats-of-arms of the Order of which he was not just a member but the son of its founder. Furthermore, it is more than likely that he gave Bosch specific instructions -differing from his usual procedure- with regard to how he should execute the work, and this explains aspects of the way the artist painted it, such as its flat surface without pictorial texture or impasto similar to that of the coats-of-arms.

With regard to the work’s dating, the information provided by the dendrochronological testing confirms that the panel could have been painted from 1488 onwards. However, to judge by its style and bearing in mind that Philip of Burgundy entered the Order of the Golden Fleece in 1501, it is most likely that Bosch painted it between that year and 1505. For the present painting, Bosch used a support of Baltic oak, over which he applied a chalk ground with an animal glue binder of the type habitual in Flemish painting and in the rest of his works. In an initial phase the underdrawing was executed using a dry, slightly greasy material so that it should not rise to the surface, as would happen with a liquid medium. Everything suggests that the artist proceeded in this manner in order to ensure that the underdrawing should not remain visible, in imitation of the coats-of-arms of the Order of the Golden Fleece to which he was making reference. By contrast to the first use of a dry underdrawing, which I have suggested reflected a specific intention on the artist’s part, in a second phase of underdrawing he used a liquid medium to strengthen outlines, folds in clothing and modelling strokes. However, rather than using the usual grey-black, here he employed whichever colour was to be applied during the painting phase. Given that they lack black, these strokes cannot be seen in the underdrawing nor would they be visible on the surface had the pictorial surface not been abraded.

In conclusion, we can say that there are numerous adjustments to the composition in the two phases of underdrawing, the first phase executed in a dry medium and the second in a liquid medium. There are also differences between the drawing and painting phases, although they are fewer in number than in other works. It is clear that the surface is smoother than usual, but there is no difference with regard to the landscape, and the manner of painting the far distance corresponds to that found in other works by Bosch, for example the background of the central panel in The Haywain Triptych (P02052). These differences reflect the way that Bosch approached this commission and its requirements. He therefore did not hesitate to use a dry material for the first phase of the underdrawing, followed by a liquid one using the same colours as the pictorial surface so that the drawn lines did not become visible on the surface, which was originally more enamel-like than it is now owing to the wear it has suffered (Text drawn from Silva, P.: Bosch. The 5th Centenary Exhibition, Museo Nacional del Prado, 2016, pp. 356-363).