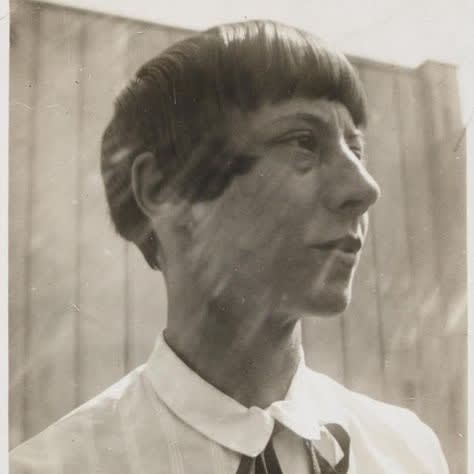

Known for her incisive and political collages and photomontages (a form she helped develop), Hannah Höch appropriated and recombined images and texts from the media to criticize popular culture, the failures of the Weimar Republic and the socially constructed roles of women. After meeting artist and writer Raoul Hausmann in 1917, Hannah Höch joined the Berlin Dada Group, a circle of predominantly male artists who satirized and criticized German culture and society after World War I. She was a member of the Dada Group. She participated in their exhibitions, including the first international Dada fair in Berlin in 1920, and her photomontages were critically acclaimed despite the condescending opinions of her male peers. Most of our male colleagues continued for a long time to regard us as charming and gifted amateurs, implicitly denying us any real professional status," she said.

The technical competence and symbolic significance of Höch's compositions refute any notion of "amateur". She has cleverly assembled photographs or photographic reproductions that she has cut out of popular magazines, illustrated journals and fashion publications, recontextualizing them in a dynamic, layered style. She has noted that "there are no limits to the materials available for pictorial collages - they are found mostly in photography, but also in writing and print, even in waste".

Höch has explored gender and identity in her work, including a humorous critique of the concept of the "new woman" in Weimar, Germany, a vision of a woman as the equal of a man. In Indian Dancer: from an ethnographic museum, she combined images of a Cameroonian mask with the face of silent film star Maria Falconetti, topped with a headdress made of kitchen utensils. Höch's amalgamation of a traditional African mask, an iconic female celebrity, and tools of domesticity refers to the avant-garde theater and fashion style of the 1920s and offers an evocative commentary on the feminist symbols of the time.

Although Berlin's Dada group broke up in the early 1920s, Höch continued to create socially critical works. She was banned from exhibiting during the Nazi regime, but remained in Germany during World War II, retiring to a house outside Berlin where she continued to work. In 1945, after the end of the war, she began exhibiting again. Before her death in 1978, her significant contribution to the German avant-garde was recognized by retrospectives of her work in Paris and Berlin in 1976.