This City Aims to Be the World's Greenest

As Singapore expands, a novel approach preserves green space.

Singapore calls itself the Garden City, and it’s making good on that promise.

Singapore's meteoric economic rise launched a landscape of towering architecture in the compact city-state, but as the metropolis continues to grow, urban planners are weaving nature throughout—and even into its heights. New developments must include plant life, in the form of green roofs, cascading vertical gardens, and verdant walls.

The push to go green extends to construction as well—green building has been mandatory since 2008.

Much of that vision to keep Singapore both sustainable and livable stems from Cheong Koon Hean, the first woman to lead Singapore’s urban development agency. The veteran architect and urban planner is credited with reshaping the skyline through landmark projects such as the waterfront residential and entertainment quarter Marina Bay—whose gardens are one of the city’s top draws—and the Jurong Lake District, slated to be a second business district and home to a new high-speed rail link to neighboring Malaysia.

Cheong is now CEO of the Housing and Development Board, which builds and manages public housing for most of Singapore’s 5.6 million people. Singapore’s sleek version of public housing emphasizes community-centric towns (there are 23) and amenities.

National Geographic spoke to her about Singapore’s unique brand of building—and how one day it may even take the city underground.

What distinguishes Singapore as an urban area?

Singapore is a both a country and a city—an island about half the size of metropolitan London. But compactness has its advantages: One can take a morning dip in the ocean and then hop on a train to work.

Singapore is truly cosmopolitan, and we’ve managed to preserve our cultural—Chinese, Indian, and Malay—and architectural legacy through a heritage conservation program. It is a merger of old and new, a mix of the East and West. These are the beautiful contradictions that make Singapore a richly diverse city.

How has Singapore transformed during your 35-year career?

When Singapore became independent in 1965, we were a city filled with slums, choked with congestion, where rivers became open sewers, and we were struggling to find decent jobs for our people. We had limited land and no natural resources. In the short span of 50 years, we have built a clean, modern metropolis with a diversified economy and reliable infrastructure. Our public housing program has transformed us from a nation of squatters to a nation of homeowners: More than 90 percent of our people own their homes, one of the highest home-ownership rates in the world.

Could you describe the initiative to expand the city’s green space?

Through an incentive program, we replace greenery lost on the ground from development with greenery in the sky through high-rise terraces and gardens. This adds another layer of space for recreation and gathering. In Marina Bay, all developments comply with a 100 percent greenery replacement policy. The Pinnacle@Duxton, the tallest public housing development in the world, has seven 50-story buildings connected by gardens on the 26th and 50th floors. You can even jog around a track on these levels, which are also equipped with exercise stations.

You’re aiming to create a model of “livable density.” Can you define that?

Given our land constraints, Singapore has no choice but to adopt high-density development. At its essence, livable density is about creating quality of life despite that density.

It’s about opportunity, variety, and convenience: More jobs result from the synergy of having so many talented people come together. We offer proximity to shops, schools, entertainment, healthcare, and the outdoors. Affordable public rail networks reduce traffic congestion. Livable density also means that we prioritize parks and recreation facilities.

Innovative design can reduce that feeling of density by creating the illusion of space using “green” and “blue” elements. We intersperse parks, rivers, and ponds amid our high-rises. These bodies of water also double as flood-control mechanisms. And we plant lushly—some three million trees cover Singapore, including a stand of virgin rainforest, rich in biodiversity, right in the heart of the island.

For a city extension called Marina Bay, we created one of the largest freshwater city reservoirs in the world and set aside 250 acres of prime real estate for the Gardens by the Bay, a “green lung” in the city.

We are also connecting our many parks into a network. Some hill parks are linked by iconic bridges, another example of how we create the illusion of space. As this park connector expands, Singaporeans will have access to a few hundred kilometers of cycling and walking trails throughout the island—they’ve already spawned a new cycling culture.

Within our public housing estates, Singaporeans build homes, start families, and form strong bonds with their neighbors. We consciously build community spaces and town plazas to create those gathering places, including “three-generation playgrounds” and fitness areas to encourage interaction between residents of different ages.

Singapore’s version of public housing is unique. Can you talk about that?

Our founding prime minister had a vision to build a nation of homeowners—to give Singaporeans a tangible stake in our country, financial security, and a critical sense of belonging.

Through the Housing and Development Board (HDB), the government builds flats [apartments] that are sold to citizens with a 99-year lease. Today HDB manages close to one million flats, housing more than 80 percent of the population. Some 95 percent of the units are owned.

Urban planning is more than just good physical design. It’s also thoughtful policy design. The flats are priced to be affordable, at about 20 to 25 percent of income. We provide choices for diverse needs and budgets, ranging from one bedroom to multigenerational flats, with four bedrooms. As it appreciates over time, the flat may be a key source of financing retirement needs. Elderly flat owners can sublet; sell off a larger flat for a smaller one; or sell part of their lease back to HDB so that the proceeds can be used to buy an annuity that provides income while they remain in their own home.

For vulnerable families who cannot afford a flat of their own, HDB helps them through its public rental program.

Looking ahead, what will Singapore be like in 2030?

Buildings will be green—a major target is to have 80 percent achieve an environmental performance rating called Green Mark by 2030, in order to reduce energy use and carbon emissions.

New solutions will support the urban lifestyle: More people will be based in Smart Work Centres—shared work space for employees from different companies—near their homes, reducing the need to travel, improving productivity, and enhancing work-life balance.

People will be empowered in new ways with technology—the elderly can be better looked after in their homes with “tele-medicine.”

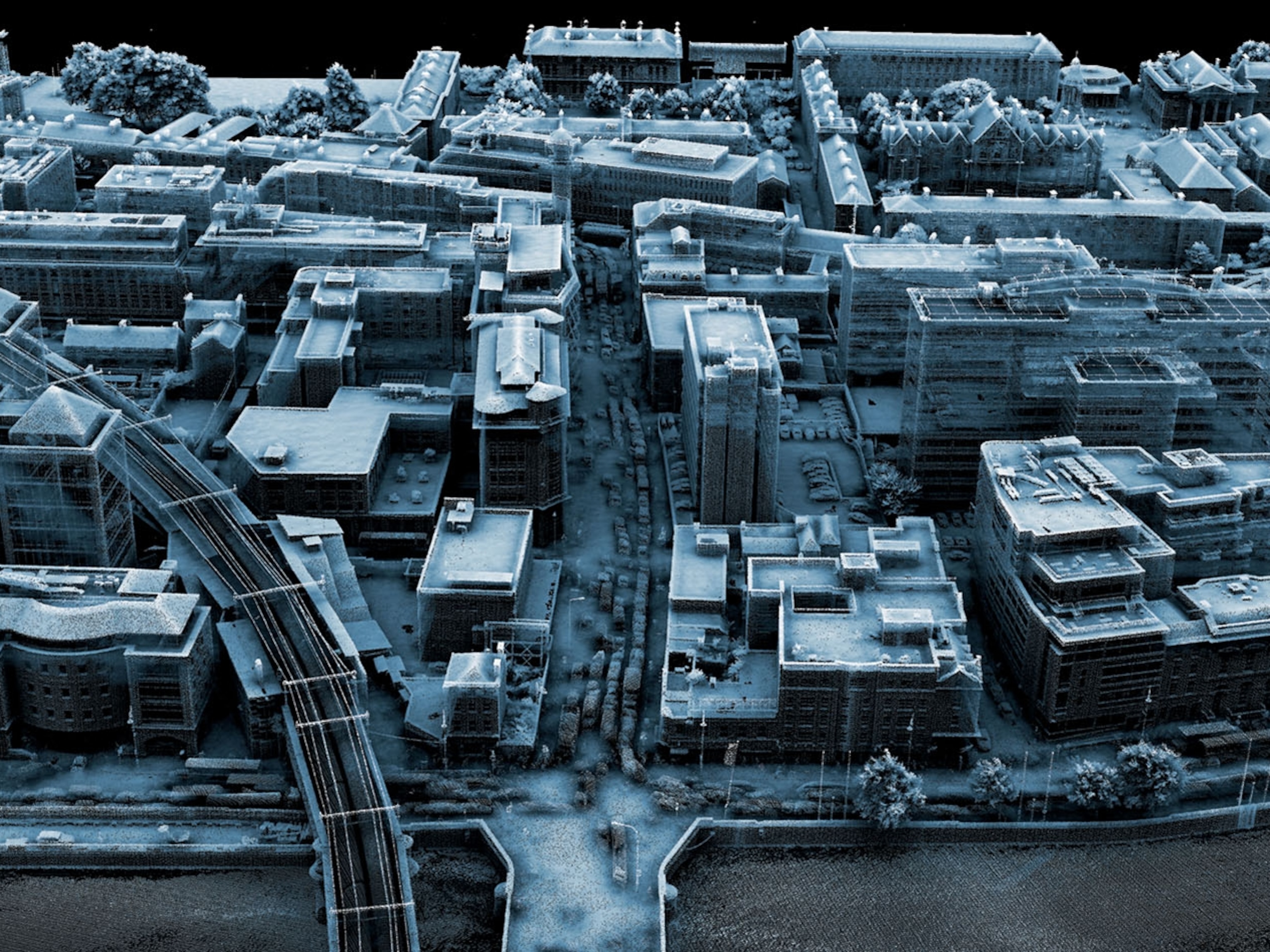

Technology will also allow us to tap underground and cavern spaces to supplement our limited land. Our urban planners are endeavoring to develop a 3-D masterplan of underground Singapore.

What can other cities learn from Singapore’s experience?

Many cities, especially those in Asia, are densely populated. Our experience shows that those cities can be livable. Our focus on equitable access to amenities and a commitment to affordable housing have provided a strong foundation for a stable society. Building up capable public institutions and harnessing public-private partnerships and technology have also been critical.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Urban Innovator explores the contributions by an individual to creating sustainable cities; the article is part of the Urban Expeditions series, which is supported by a grant from United Technologies to the National Geographic Society.

Go Further

Animals

- How can we protect grizzlies from their biggest threat—trains?How can we protect grizzlies from their biggest threat—trains?

- This ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thoughtThis ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thought

- Why this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect senseWhy this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect sense

- When did bioluminescence evolve? It’s older than we thought.When did bioluminescence evolve? It’s older than we thought.

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

Environment

- Are the Great Lakes the key to solving America’s emissions conundrum?Are the Great Lakes the key to solving America’s emissions conundrum?

- The world’s historic sites face climate change. Can Petra lead the way?The world’s historic sites face climate change. Can Petra lead the way?

- This pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilienceThis pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilience

- Listen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting musicListen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting music

History & Culture

- Meet the original members of the tortured poets departmentMeet the original members of the tortured poets department

- Séances at the White House? Why these first ladies turned to the occultSéances at the White House? Why these first ladies turned to the occult

- Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?

- Beauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century SpainBeauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century Spain

Science

- Here's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in spaceHere's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in space

- Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.

- NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

Travel

- How to see Mexico's Baja California beyond the beachesHow to see Mexico's Baja California beyond the beaches

- Could Mexico's Chepe Express be the ultimate slow rail adventure?Could Mexico's Chepe Express be the ultimate slow rail adventure?