The hellish history of the devil: Satan in the Middle Ages

In the Middle Ages European artists and theologians shaped a new terrifying vision of Satan and the punishments awaiting sinners in his realm.

Perhaps the devil’s most famous depiction was crafted by English poet John Milton in his 1667 masterpiece, Paradise Lost. The epic poem tells two stories: one of the fall of man and the other the fall of an angel. Once the most beautiful of all angels, Lucifer rebels against God and becomes Satan, the adversary, who is:

Hurld headlong flaming from th’ Ethereal Skie

With hideous ruine and combustion down

To bottomless perdition, there to dwell

In Adamantine Chains and penal Fire . . .

To develop his character, Milton relied on an idea of the devil that had been evolving throughout the Middle Ages and early Renaissance: the foe of God and man, the master of witches, and the tempter of sinners. This personage was largely fixed in the collective consciousness of Christendom, but the devil’s origins are complex, coming from many places, not just the Bible.

The Christian Bible devotes only a few passages to the devil and does not describe his appearance. In Genesis the serpent who tempts Eve is strongly associated with Satan, but many theologians think the composition of Genesis predates the concept of the devil. Passages alluding to Lucifer’s fall can be found in the books of Isaiah and Ezekiel. The Old Testament’s Satan is not the opponent of God, but rather an adversary as exemplified by his role in the Book of Job. (See also: Halloween: costumes, history, myths and more)

Blue Devils?

The oldest representation of the Christian idea of the devil may be this mosaic in the Basilica of Sant’Apollinare Nuovo, Ravenna, Italy. The sixth-century mosaic shows Jesus Christ, dressed in royal purple, seated at the Last Judgment. He is separating the souls of the saved (symbolized by sheep) from the souls of the damned (the goats). Behind the sheep stands a red angel, and behind the damned is a blue angel. Both angels wear halos, a device originally seen as a symbol of power, but not necessarily of sanctity. The blue figure may be Lucifer, the fallen angel later known as Satan. Unlike later depictions, he is beautiful and radiant—not the horned, hoofed, red monster of later depictions. The color of the holy kingdom in the sixth century, red became associated with hellfire and the devil in later centuries.

In the New Testament Satan has become a force of evil. He tempts Jesus to abandon his mission: “All these I will give you, if you will fall down and worship me” (Matthew 4:9). He is described as a hunter of souls: The First Epistle of Peter warns: “Discipline yourselves, keep alert. Like a roaring lion your adversary the devil prowls around, looking for someone to devour” (I Peter 5:8). By the Book of Revelation, Satan has become an apocalyptic beast, determined to overthrow god and heaven.

The two devils of the Old and New Testaments are first connected in the Vulgate, a fourth-century A.D. translation of the Hebrew Bible into Latin. Isaiah 14 refers to an earthly king as Lucifer, meaning “bearer of light,” who falls from heaven. Echoing Isaiah’s image, Jesus says in Luke 10:18: “I watched Satan fall from heaven like a flash of lightning.” At the dawn of the Middle Ages in the fifth century, authors began to apply the Vulgate term for Isaiah’s Lucifer to the rebellious angel leader in the Book of Revelation, cast into the pit along with his evil minions.

Devilish Themes

Old Gods and the New

During the Middle Ages the devil’s appearance changed drastically. A sixth-century mosaic from Basilica of Sant’Apollinare Nuovo in Ravenna, Italy, shows the Last Judgment, and the satanic figure appears as an ethereal blue angel. This angelic imagery will ultimately be shed in favor of a more demonic appearance.

Many of the devil’s animalistic traits can be traced back to influences from earlier religions. One of the first was found in ancient Babylonian texts—wicked demons named Lilitu. These winged female demons flew through the night, seducing men and attacking pregnant women and infants. In the Jewish tradition, this demoness evolved into Lilith, Adam’s first wife. Lilith came to embody lust, rebellion, and ungodliness, traits later linked to the Christian devil. Another ancient deity who became associated with Satan was Beelzebub, which translates roughly to “Lord of the Flies.” Beelzebub was a Canaanite deity, named in the Old Testament as a false idol that the Hebrews must shun.

Classical influences also played a role in the development of the Christian devil. As Christianity took root in the Roman world, early worshipers rejected pagan gods and believed them to be evil spirits. Pan, half goat and half man, was a lusty god of nature whose carnal appetites made him easy to associate with the forbidden. His goat horns and cloven hooves became synonymous with sin and would later be adopted by artists in their horrific images of the devil. (See also: Krampus the Christmas devil is coming to more towns. So where's he from?)

Reproduced in pictures, from the great artists down to the humble village artisan, a reptilian, winged figure of damnation became the iconic devil figure. Artists like Giotto and Fra Angelico often depicted the devil in paintings of the Last Judgment. In them, a ravenous Satan is seated in the center of hell as he gleefully chomps on the souls of sinners.

The devil’s image was further reflected in one of the world’s most influential literary works: Dante’s Inferno, published in the early 14th century as part of the Divine Comedy. Dante describes the deepest regions of hell where Satan holds sway. The devil has three faces and “At every mouth he with his teeth was crunching / A sinner . . . / So that he three of them tormented thus.” Satan bears “mighty wings . . . / No feathers had they, but as of a bat.”

Active Evil

Theologically, the idea of the devil changed during this period as well. His role in the early Middle Ages was much like his role in the Old Testament: He was an adversary but not an active enemy. Throughout the Middle Ages Satan evolved into an aggressive, malignant force set on tormenting as many human souls as possible.

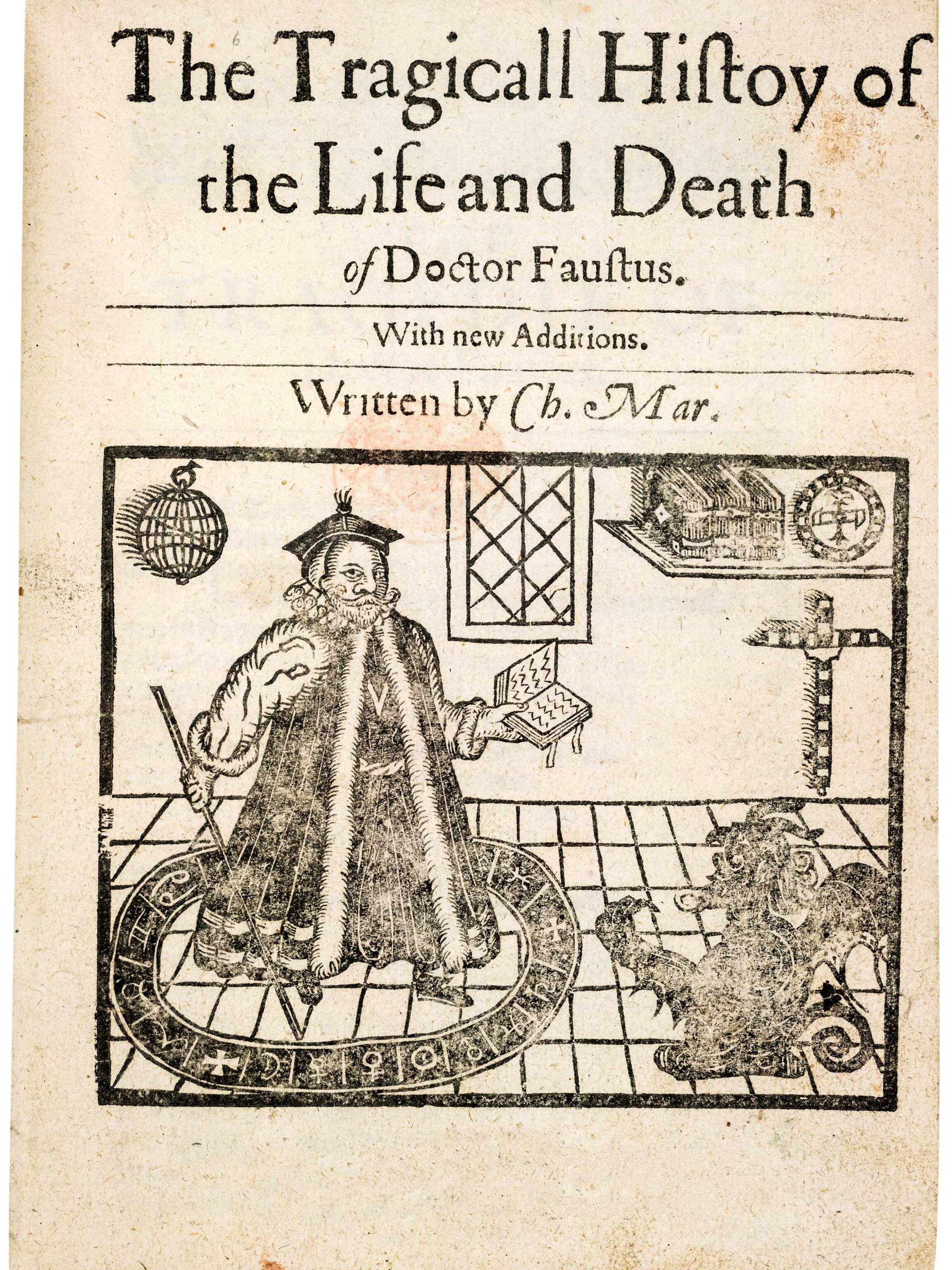

The Greek daimon—a spirit or minor divinity who engaged with humans—informed a key aspect of this new devil. From the third century A.D., a mystical philosophy known as Neoplatonism incorporated theurgy, invoking daimons to request favors. Neoplatonism was not wholly incompatible with Christianity, but communicating with spirits was. Rituals could not sway the Christian God into granting human wishes; prayers were only evidence of piety. If daimons were indeed doing a person’s bidding, they had to be in league with Satan, who “helped” mortals to deceive them and cause their downfall.

Spirit Summoning

Some insights into the rituals of the medieval necromancer can be gleaned through the manuals that they used. The best known are those that passed on the supposed magic powers of the biblical king Solomon.The Key of Solomon (Clavicula Salomonis) is generally agreed to be a 14th-century work that contains invocations to demons imploring them for power. The text includes blasphemous supplications to God asking that the demons obey. In the section entitled “The Prayer,” the necromancer is instructed to intone: “Here ye, and be ye ready, in whatever part of the Universe ye may be, to obey the voice of God, the Mighty One, and the names of the Creator. We let you know by this signal and sound that ye will be convoked hither . . . to obey our commands.” This being done, let the Master complete his work, renew the Circle, and make the incensements and fumigations.

As more ancient works were translated into Latin throughout the Middle Ages, a new movement, Scholasticism, tried to reconcile the teachings of the early church with pagan writings on science, philosophy, and even necromancy, the art of conjuring spirits and demons. Necromancers were courting damnation through exposure to demons. In 1326 Pope John XXII issued a bull, Super illius specula, which stated that anyone found guilty of engaging in necromancy could be condemned for heresy and burnt at the stake.

During the 14th century Europe faced a dark period blighted by the Black Death, famine, and war. Fear of the devil and his influence increased, as evidenced by an explosion of witch hunts. Unlike necromancers, the church believed that the devil sought out women as partners; witches would sign pacts and engage in evil on his behalf. People were no longer seen as merely deceived by Satan, but in active collusion with him against God. By this time in European history, the devil no longer sat passively. Taking an active role, Satan is present in the world, stealing souls and recruiting people to do his bidding.

Marina Montesano is professor of Medieval history at the University of Messina, Italy.

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- This fungus turns cicadas into zombies who procreate—then dieThis fungus turns cicadas into zombies who procreate—then die

- How can we protect grizzlies from their biggest threat—trains?How can we protect grizzlies from their biggest threat—trains?

- This ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thoughtThis ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thought

- Why this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect senseWhy this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect sense

Environment

- Your favorite foods may not taste the same in the future. Here's why.Your favorite foods may not taste the same in the future. Here's why.

- Are the Great Lakes the key to solving America’s emissions conundrum?Are the Great Lakes the key to solving America’s emissions conundrum?

- The world’s historic sites face climate change. Can Petra lead the way?The world’s historic sites face climate change. Can Petra lead the way?

- This pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilienceThis pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilience

- 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting music30 years of climate change transformed into haunting music

History & Culture

- When treasure hunters find artifacts, who gets to keep them?When treasure hunters find artifacts, who gets to keep them?

- Meet the original members of the tortured poets departmentMeet the original members of the tortured poets department

- When America's first ladies brought séances to the White HouseWhen America's first ladies brought séances to the White House

- Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?

Science

- Should you be concerned about bird flu in your milk?Should you be concerned about bird flu in your milk?

- Here's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in spaceHere's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in space

- Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.

Travel

- This striking city is home to some of Spain's most stylish hotelsThis striking city is home to some of Spain's most stylish hotels

- Photo story: a water-borne adventure into fragile AntarcticaPhoto story: a water-borne adventure into fragile Antarctica

- Germany's iconic castle has been renovated. Here's how to see itGermany's iconic castle has been renovated. Here's how to see it

%20-%20Saint%20Romain_square.jpg)