Abstract

Giant fibrovascular polyp of the esophagus is a descriptive diagnostic term intended to encompass rare, large, polypoid esophageal masses composed of fibroadipose tissue. Despite sometimes dramatic clinical presentations, they have historically been considered to represent reactive, non-neoplastic proliferations. Recently, however, a small number of reports have described well-differentiated liposarcomas of the esophagus, mimicking giant fibrovascular polyps. In order to clarify the relationship between esophageal liposarcoma and giant fibrovascular polyp, we retrieved esophageal cases coded as ‘giant fibrovascular polyp,’ ‘lipoma’ and ‘liposarcoma’ from our archives and re-examined their clinicopathologic features and MDM2 amplification status. Thirteen cases were identified (lipoma (n=1), giant fibrovascular polyp (n=5), well-differentiated liposarcoma (n=3), dedifferentiated liposarcoma (n=3)). The tumors ranged from 5.2 to 19.5 cm and arose predominantly in the cervical esophagus. All consisted chiefly of mature adipose tissue, with a variable component of fibrous septa. In all cases, close inspection of these fibrous septa showed them to contain an increased number of slightly enlarged spindled cells with irregular, hyperchromatic nuclei, similar to those seen in some well-differentiated liposarcomas. Three cases, all previously classified as dedifferentiated liposarcoma, showed in addition solid zones of non-lipogenic spindle cell sarcoma. By fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), all cases showed MDM2 amplification, confirming diagnoses as well-differentiated (N=10) and dedifferentiated (N=3) liposarcoma. Clinical follow-up (8 cases, range 22–156 months, median 33 months) showed 3 patients with local recurrences (1 well-differentiated and 2 dedifferentiated liposarcomas), 1 patient with liver metastases (dedifferentiated liposarcoma) and 2 deaths from disease (both dedifferentiated liposarcomas). These results suggest that the great majority of large, polypoid, fat-containing masses of the esophagus represent well and dedifferentiated liposarcoma, rather than ‘giant fibrovascular polyps.’ We suggest that the diagnosis of ‘giant fibrovascular polyp’ should be made with great caution in the esophagus, and only after careful morphological study and MDM2 FISH has excluded the possibility of liposarcoma.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

The term ‘giant fibrovascular polyp’ of the esophagus was first proposed by Stout and Lattes in 1957 as a unifying appellation for polypoid esophageal lesions lined by benign squamous mucosa and containing variable amounts of fibrous tissue and mature fat, previously classified as ‘fibroma’ or ‘fibrolipoma’ depending on the relative percentage of each component.1, 2 Stout and Lattes believed these to represent reactive, non-neoplastic lesions, a now generally accepted concept.2, 3 The clinical presentation of esophageal giant fibrovascular polyps can be dramatic, with reports of patients regurgitating tumors and examples of death from asphyxiation.4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 The largest series of giant fibrovascular polyps of the esophagus is that of Levine et al (16 cases).10

In the years since the seminal description of Stout and Lattes, a small number of cases of esophageal well-differentiated liposarcoma mimicking giant fibrovascular polyp have been reported.11, 12, 13 As in their more common somatic soft tissue locations, esophageal well-differentiated liposarcomas consist of mature adipose tissue transected by irregular fibrous septa containing scattered enlarged, hyperchromatic stromal cells, showing MDM2 and/or CDK4 overexpression by immunohistochemistry, and MDM2 amplification by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH).11, 12, 13

Over the past several years, we have encountered similar cases of polypoid esophageal well-differentiated liposarcoma as well as rare cases of esophageal dedifferentiated liposarcoma.14 Prompted by these events, we undertook a more comprehensive study of polypoid, fat-containing masses of the esophagus, with the goal of determining the relationship between giant fibrovascular polyp and esophageal liposarcoma.

Materials and methods

This study was approved by the Mayo Clinic Review Board. Esophageal masses previously coded as representing ‘giant fibrovascular polyp,’ ‘lipoma,’ ‘atypical lipomatous tumor,’ ‘well-differentiated liposarcoma’ and ‘dedifferentiated liposarcoma’ were retrieved from our institutional and consultation archives for the time period 1 January 1995 to 31 December 2014. The terms ‘atypical lipomatous tumor’ and ‘well-differentiated liposarcoma’ had been applied in an ad hoc fashion, as a clear consensus as to the best terminology in this anatomical location does not exist. For the purposes of this paper, such cases will be referred to as ‘well-differentiated liposarcoma.’

All cases were re-reviewed by 3 of the authors (RPG, SY and ALF). A representative tissue block was chosen for MDM2 FISH. MDM2 FISH was performed at Mayo Clinic using a previously reported probe set and technique.15 The FISH signals were interpreted independently by two experienced FISH technologists and re-reviewed by a cytogeneticist (PTG). A minimum of 50 nuclei were scored for each case. Given the variable adipocytic extent in these lesions, we also examined multiple fields in all cases to assess for uniformity of the FISH findings. Clinical information including tumor size, location in the esophagus, imaging features and clinical follow-up were obtained, where possible.

Results

Thirteen cases were identified, including cases originally diagnosed as giant fibrovascular polyps (N=5), well-differentiated liposarcomas (N=4), dedifferentiated liposarcomas (N=3) and lipoma (N=1). Table 1 summarizes the clinicopathological features of these cases. Clinical follow-up was available for 8 cases (61%) (range 22–156 months, median 33 months). Local recurrences were seen in 3 patients, one with well-differentiated liposarcoma (case 2) and 2 with dedifferentiated liposarcoma (cases 5 and 8). These 2 patients with dedifferentiated liposarcoma died of disease, one from unresectable local disease at 12 months of follow-up (case 5) and one from liver metastases at 37 months of follow-up (case 8). The 3rd patient (case 2), whose well-differentiated liposarcoma recurred at 156 months, underwent additional surgical resection for this and was reported to have died of apparent cardiac disease at 157 months of follow-up. Local recurrences and/or metastases were not noted in any of the remaining patients with clinical follow-up.

Five of 13 cases were originally submitted to us in consultation, including 4 well-differentiated liposarcomas and one dedifferentiated liposarcoma. Diagnoses suggested for these cases by the referring pathologist included giant fibrovascular polyp (4 cases) and ‘spindle cell neoplasm’ (1 case).

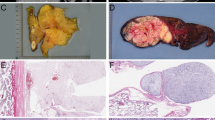

All tumors presented as pedunculated polypoid masses which partially obstructed the esophageal lumen (Figure 1a). Several were very large and extended from the cervical esophagus down to the level of the thoracic esophagus. Radiology reports (available for 7 cases) described ‘sausage-shaped’ lesions arising at the level of the proximal or cervical esophagus. In 2 cases without radiology reports, the masses were described clinically as involving the mid and distal esophagus. In one patient (case 5) with a dedifferentiated liposarcoma, the mass was described as growing on an intra-esophageal stalk, with extension through the esophageal wall into the anterior mediastinum.

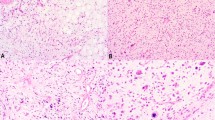

Well-differentiated liposarcoma of the esophagus, presenting as a large, polypoid, fibro-fatty mass (a) of the esophagus with overlying squamous mucosa (b). Close inspection of the fibrous septa between the adipocytes revealed an increased number of stromal cells with slightly irregular, hyperchromatic nuclei (c). Fluorescence in situ hybridization for MDM2 amplification was positive.

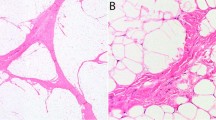

Microscopically, the tumors were centered in the subepithelial stroma, and were lined in almost all instances by intact squamous mucosa (Figure 1b). All tumors consisted of an admixture of mature adipose tissue and fibrous zones (Figures 1a and 2a), although the relative percentages of these two components were highly variable, with some tumors showing easily identified fibrous septa (Figure 1c) and others containing only very delicate fibrovascular septa (Figure 2b). In all cases, close examination of the fibrous septa revealed slightly enlarged, hyperchromatic stromal cells, although the number of such cells was highly variable. Interestingly, the hyperchromatic stromal cells seen in these esophageal lesions were somewhat ‘subtle,’ typically displaying a lesser degree of nuclear enlargement and irregularity than seen in most somatic soft tissue well-differentiated liposarcomas (Figures 1b and 2b). The 3 dedifferentiated liposarcomas showed in addition significant zones of mitotically active, variably pleomorphic, non-lipogenic spindle cell sarcoma, in one instance showing a whorled, ‘perineurioma-like’ growth pattern (Figures 3a and b).

‘Lipoma-like’ well-differentiated liposarcoma of the esophagus (a). This case was initially diagnosed as an esophageal ‘lipoma.’ On re-review, however, scattered fibrous septa containing hyperchromatic spindle cells were identified (b). Fluorescence in situ hybridization for MDM2 amplification was positive.

Dedifferentiated esophageal liposarcoma, presenting clinically as a ‘giant fibrovascular polyp’ (a). The dedifferentiated component of this tumor consisted of a whorled, ‘perineurioma-like’ proliferation of mitotically active, non-lipogenic spindled cells (b). Fluorescence in situ hybridization for MDM2 amplification was positive.

MDM2 amplification by FISH was identified in 13 (of 13) cases, and was present in adipocytic, fibrous and dedifferentiated areas (Figure 4).

Discussion

Giant fibrovascular polyps of the esophagus are rare, and have traditionally been thought to represent non-neoplastic, reactive lesions, possibly related to mechanical traction within the esophageal lumen.2 However, over the past several years, with more widespread use of ancillary immunohistochemical and molecular cytogenetic tests for well-differentiated liposarcoma-associated genetic events (eg, MDM2 and CDK4 overexpression and/or amplification), it has become increasingly apparent that cases reportedly showing ‘classical’ morphological features of giant fibrovascular polyp may show ring or marker chromosomes with regional amplification of chromosome 12q13-21 (the genetic hallmarks of well-differentiated liposarcoma),16 and that cases of morphologically typical well-differentiated liposarcoma may clinically mimic giant fibrovascular polyp.11, 12, 13, 17, 18, 19 These previous findings, and our own recent clinical experience, suggested to us the possibility that most (if not all) esophageal giant fibrovascular polyps represent well-differentiated and dedifferentiated liposarcomas.

We believe the results of the present study support this hypothesis. We have identified MDM2 amplification both within mature-appearing fat and the surrounding fibrovascular septa in all studied cases, including 5 cases previously diagnosed in our own laboratory as ‘giant fibrovascular polyp.’ These represented older archival cases; more recent cases submitted in consultation as ‘giant fibrovascular polyps’ had been interpreted by us as representing well-differentiated liposarcoma, based on morphological and molecular cytogenetic findings. In this regard, it is important to emphasize that the morphological features of esophageal well-differentiated liposarcoma seem typically to be less impressive than those of their soft tissue and retroperitoneal counterparts, usually lacking markedly pleomorphic, hyperchromatic stromal cells, and showing instead an increased number of slightly enlarged stromal cells with irregular, hyperchromatic nuclei. An additional 3 cases, clinically thought to represent ‘giant fibrovascular polyps,’ showed instead morphologically typical, MDM2-amplified dedifferentiated liposarcoma, further suggesting that most if not all ‘giant fibrovascular polyps’ are in fact esophageal liposarcomas. Interestingly, Figure 11 from Stout and Lattes’ Fascicle on Tumors of the Esophagus (1st Edition), illustrates areas within a ‘giant fibrovascular polyp’ of the esophagus that we would interpret as showing features of well-differentiated liposarcoma, including mature adipose tissue transected by irregular fibrous bands containing an increased number of slightly enlarged, hyperchromatic stromal cells.1

Esophageal well-differentiated liposarcomas are quite rare, with fewer than 50 reported cases, inclusive of the present series.20 The natural history of esophageal liposarcomas, many of which have presented as large polypoid masses similar to those in the present series, appears to be similar to that of their more common somatic soft tissue counterparts, with potential for local recurrence and dedifferentiation, and eventual metastatic risk in dedifferentiated tumors. Because these tumors seem to have a relatively high risk for local recurrence and/or dedifferentiation, we would suggest using the term ‘well-differentiated liposarcoma’ in this anatomical location, rather than ‘atypical lipomatous tumor.’

In summary, we have identified morphological and molecular cytogenetic features of well-differentiated and dedifferentiated liposarcoma in 13 large, polypoid fibroadipose tumors of the esophagus, all presenting clinically as ‘giant fibrovascular polyps.’ These findings strongly suggest that giant fibrovascular polyp may not represent a specific, reactive pseudoneoplasm of the esophagus, but is instead a distinctive clinicopathological presentation of liposarcoma. We suggest that the diagnosis of ‘giant fibrovascular polyp’ should be made with great caution in the esophagus, and only after careful morphological study and MDM2 FISH has excluded the possibility of liposarcoma. Recognition of esophageal well-differentiated liposarcomas, and appreciation of their unusual polypoid growth pattern and sometimes subtle morphological features, is critical for the correct clinical management of patients with this rare disease.

References

Chi PS, Adams WE . Benign tumors of the esophagus; report of a case of leiomyoma. Arch Surg 1950;60:92–101.

Stout AP, Lattes R . Tumors of the Esophagus (Fascicle 20). Armed Forces Institute of Pathology: Washington D.C., 1957;25–29 pp.

Lewin KJ, Appelman HD . Tumors of the Esophagus and Stomach Third Series ed. 1995.

Owens JJ, Donovan DT, Alford EL et al. Life-threatening presentations of fibrovascular esophageal and hypopharyngeal polyps. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 1994;103:838–842.

Lee KN, Auh JY, Nam KJ et al. Regurgitated giant fibrovascular polyp of the esophagus. Am J Roentgenol 1996;166:730.

Iriarte G, Baez J, Gomez J et al. Esophageal fibrovascular polyp protruding from the mouth. Dis Esophagus 1997;10:69–70.

Sargent RL, Hood IC . Asphyxiation caused by giant fibrovascular polyp of the esophagus. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2006;130:725–727.

Sweeney T . Giant fibrovascular polyp causing complete oesophageal obstruction. ANZ J Surg 2011;81:845–846.

Park JS, Bang BW, Shin J et al. A case of esophageal fibrovascular polyp that induced asphyxia during sleep. Clin Endosc 2014;47:101–103.

Levine MS, Buck JL, Pantongrag-Brown L et al. Fibrovascular polyps of the esophagus: clinical, radiographic, and pathologic findings in 16 patients. Am J Roentgenol 1996;166:781–787.

Valiuddin HM, Barbetta A, Mungo B et al. Esophageal liposarcoma: well-differentiated rhabdomyomatous type. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2016;8:835–839.

Boni A, Lisovsky M, Dal Cin P et al. Atypical lipomatous tumor mimicking giant fibrovascular polyp of the esophagus: report of a case and a critical review of literature. Hum Pathol 2013;44:1165–1170.

Jakowski JD, Wakely PE Jr . Rhabdomyomatous well-differentiated liposarcoma arising in giant fibrovascular polyp of the esophagus. Ann Diagn Pathol 2009;13:263–268.

Torres-Mora J, Moyer A, Topazian M et al. Dedifferentiated liposarcoma arising in an esophageal polyp: a case report. Case Rep Gastrointest Med 2012;2012:141693.

Boland JM, Weiss SW, Oliveira AM et al. Liposarcomas with mixed well-differentiated and pleomorphic features: a clinicopathologic study of 12 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 2010;34:837–843.

Yu Z, Bane BL, Lee JY et al. Cytogenetic and comparative genomic hybridization studies of an esophageal giant fibrovascular polyp: a case report. Hum Pathol 2012;43:293–298.

Ward MA, Beard KW, Teitelbaum EN et al. Endoscopic resection of giant fibrovascular esophageal polyps. Surg Endosc 2017; doi: 10.1007/s00464-017-5664-0 [e-pub ahead of print].

Beylergil V, Simmons MZ, Ulaner G et al. FDG PET/CT findings in a rare case of giant fibrovascular polyp of the esophagus harboring atypical lipomatous tumor/well-differentiated liposarcoma. Clin Nucl Med 2014;39:288–291.

McQueen C, Montgomery E, Dufour B et al. Giant hypopharyngeal atypical lipomatous tumor. Adv Anat Pathol 2010;17:38–41.

Riva G, Sensini M, Corvino A et al. Liposarcoma of hypopharynx and esophagus: a unique entity? J Gastrointest Cancer 2016;47:135–142.

Acknowledgements

We thank Darlene Knutson, Ryan Knudson and Sara Kloft-Nelson for excellent technical work on fluorescence in situ hybridization. We would also like to thank the Division of Anatomic Pathology Research committee for funding support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Graham, R., Yasir, S., Fritchie, K. et al. Polypoid fibroadipose tumors of the esophagus: ‘giant fibrovascular polyp’ or liposarcoma? A clinicopathological and molecular cytogenetic study of 13 cases. Mod Pathol 31, 337–342 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2017.140

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2017.140