LOS ANGELES — As a 17-year-old attending San Fernando Senior High School, Monica Rodriguez remembers the day in 1992 when the events that became known as the L.A. riots broke out.

It was “the longest night of my life,” Rodriguez, a Los Angeles City Council member, said.

She spent the night waiting to get news of her father, a firefighter stationed in the predominantly Latino neighborhood of Boyle Heights. She said she later found out several bullets had narrowly missed him, after gunfire from semiautomatic weapons pierced the firetruck's windshield.

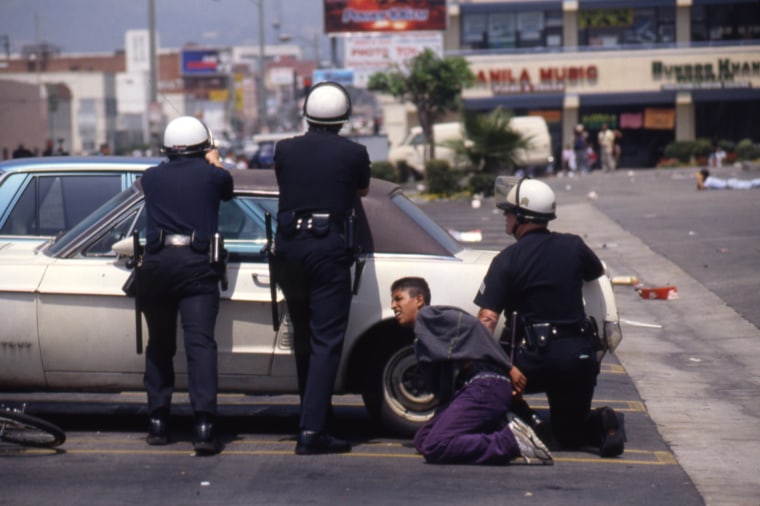

Following the acquittal of nearly all charges against four police officers captured on camera beating Black motorist Rodney King, the city convulsed for days with deadly violence and protests, resulting in over $775 million in damages.

Though the L.A. riots were seen primarily as a response from the Black community to the police officers' verdict, news and research reports noted that of the 63 deaths between April 29 and May 4, nearly a third were Latinos. Of those arrested by police as involved in riots, 51 percent were Hispanic. The majority of the offenses were breaking curfew and civil disturbances.

In addition, according to numerous reports, including the official Los Angeles riots report, over 1,000 people in primarily Latino immigrant areas were deported.

“The unrest occurred all over Los Angeles,” said Manuel Pastor, distinguished professor of sociology and American studies and ethnicity and the Turpanjian chair in civil society and social change at the University of Southern California.

"Part of it was driven by a reaction to racist policing," Pastor said, "in neighborhoods that were twice as poor, twice as unemployed and were about 50 percent Latino, and that meant that Latinos were a very important but underwritten part of the story — and then also became an unwritten part of the solutions being suggested."

A law enforcement arc ‘bent towards building trust’

Aurea Montes-Rodriguez, the executive vice president at Community Coalition in South L.A., was a high school senior at the time of the riots.

In the period leading up to the 1992 uprisings, the crack cocaine epidemic hit the community. As a result, the relationship between law enforcement and residents changed, especially for the youth.

In one experience, Montes-Rodriguez recalls being in the car with her brother when they were stopped by a police officer, who said they made an illegal left turn. The police officer, she said, pointed his rifle in her brother’s direction, and she was told a derogatory word and to stay quiet so nothing would happen to him.

“Three decades later, it’s easy to forget just how antagonistic those relationships were, and how normalized they had become,” Montes-Rodriguez said.

In spite of some setbacks, Montes-Rodriguez thinks the relationship between the Latino community and law enforcement has improved significantly. Noting that firefighter and police jobs have evolved in the last 30 years, Montes-Rodriguez is focused on reform.

“In order to provide the best service to people, we have to change,” she said.

In terms of the criminal justice system in the last 30 years, the Los Angeles Police Department force has grown from 21 percent to over 50 percent Latino.

But there's still work to be done, Latino advocates say. A 2019 Los Angeles Times analysis found that Blacks and Latinos were searched significantly more than whites during traffic stops by police, even though whites were more likely to be found with illegal items.

LAPD Police Chief Michel Moore told NBC News the ongoing relationship between law enforcement and the community is an arc “bent towards building trust.”

“We have to — must recognize — own our past and the ghosts of our past,” Moore said, “and at the same time, ask every Angeleno and every individual who may have had an unfortunate, or felt that they were treated in a prejudiced or biased manner, to work forward with us and lead with us.”

Following the uprisings, a shift toward added transparency has included a series of reforms that set term limits for police chiefs, appointed Willie Williams as the first Black LAPD chief, started several internal investigations and installed added technology that allowed the auditing of messages.

A 'levantamiento'

Pastor said he views the riots as an uprising — or as he calls it, a “levantamiento” — for Latinos that spoke to the anger “particularly in the early 1990s” and the effects of people squeezed by economic conditions.

He said he sees the riots as a moment in which Latino identity was reshaped in Los Angeles, because it signaled a community that wasn’t just Mexican American, but also immigrant and Central American.

During and following the riots, Latinos in Los Angeles and surrounding areas worked to organize and rebuild. Some activists remember the example of actor Edward James Olmos, who went on different local TV stations and urged residents, in English and Spanish, to stay home amid the turbulence. He later joined clean-up efforts in South Los Angeles with other community members.

Pastor pointed out that in the early 1990s and specifically after the riots, unions and elected officials began to organize Latinos and immigrants in a more cohesive way to fight for workers’ rights and against ballot initiatives targeting Latinos and immigrants.

Powering through 'adversity'

Montes-Rodriguez said the anniversary feels different given the amount of loss experienced by Latinos in the last two years due to the Covid pandemic.

The pandemic has exposed ongoing healthcare inequities, Montes-Rodriguez pointed out. Yet her group and 20 others came together and pushed elected officials to focus on more funding and services for testing and vaccination in Black and Latino communities that the pandemic hit hardest.

“All of these changes from this pandemic really point to the power of organized people and the work that organizations like Community Coalition have committed themselves to because of the period that led to the 1992 uprising,” she said.

While challenges remain for Latino and other nonwhite communities in the city, Monica Rodriguez, the City Council member, remains hopeful.

"What keeps me going through these difficult times me going through all of the difficult times is the fact that our community has continued to power through so much adversity,” she said. “It’s the streFollow NBC Latino on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram. is the fact that our community has continued to power through so much adversity. It’s the strength of the Latino community. This is just who we are.”

Follow NBC Latino on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.