As the Hollywood screenwriters’ strike enters its third week, Black picketers see the push for better pay and contract terms as a way to fortify hard-won gains that they say aren’t generating sufficient returns for creators of color.

The Writers Guild of America kicked off its strike May 2, bringing much of the entertainment industry to a halt after failed negotiations triggered the first walkout in nearly 15 years.

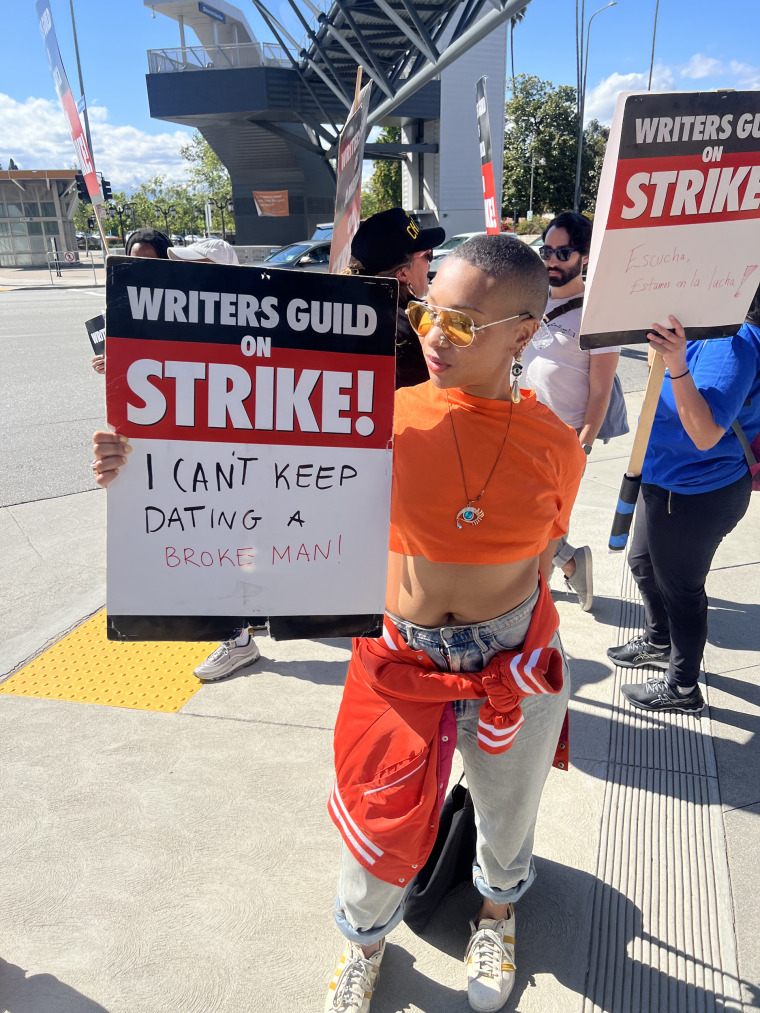

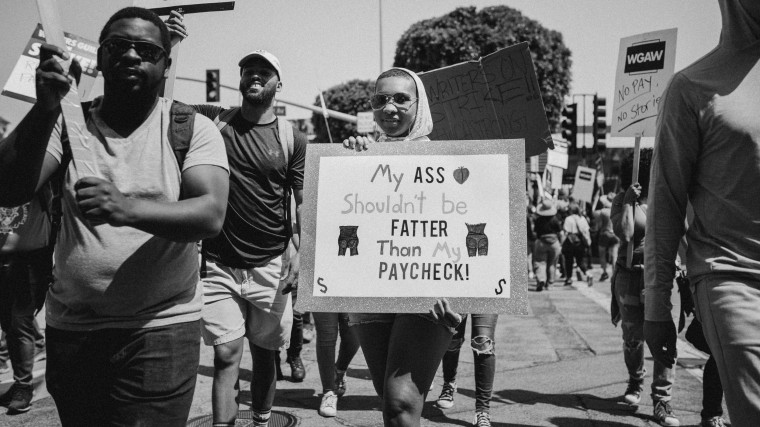

For weeks, thousands of writers have campaigned for pay increases and changes to a streaming-based business model that many say has imperiled their livelihoods. Black guild members see the fight as bound up with another one: Improved representation in TV and movies, they say, has come at the cost of sustainable careers for the very writers driving that progress.

After nationwide mass protests against the police murder of George Floyd in 2020, streaming operators including Netflix, Disney+ and Amazon Prime Video joined a wave of major companies that publicly committed to improve racial equity in their ranks and products.

Since then, streamers have by some measures earned higher marks for diversity than their traditional counterparts: Minority writers were credited in 20% of streaming films last year, compared to 12.4% of theatrical releases, according to UCLA’s latest Hollywood Diversity Report.

But some in the industry say work on the streaming side in particular is becoming more precarious and less remunerative.

“They don’t really give shows a chance to find an audience the same way that they used to,” said Kyra Jones, 30, a Los Angeles-based writer and actor.

The last two projects Jones wrote for — “Queens,” a musical drama that aired on ABC’s broadcast network featuring the R&B singer Brandy and the rapper Eve, and “Woke,” a comedy that streamed on Hulu about an on-the-verge cartoonist — were canceled after one and two seasons, respectively.

Jones said her work on “Queens” has netted her at least $16,000 from residuals, or compensation for content syndication or streams, compared to just $6,000 for “Woke.”

Among the WGA’s demands is that studios reconcile pay disparities between broadcast and streaming like the one Jones pointed to. The guild also says streaming shows are canceled more frequently, creating less stable schedules for creators as entertainment giants continue to lean into their streaming offerings.

What’s being missed is just how much compensation for writers has shifted with the new era of television.

— Charlene Polite Corley, Nielsen

A recent WGA survey found that the median weekly pay for writer-producers has shrunk by 23% over the last 10 years when adjusted for inflation.

“What’s being missed is just how much compensation for writers has shifted with the new era of television,” said Charlene Polite Corley, a vice president and the head of diverse insights and initiatives at Nielsen.

A spokesperson for the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers, which represents major media companies in negotiations with the WGA, referred to previous statements about the strike, saying that hiring quotas are “incompatible with the creative nature of our industry” and that “writers have only recently begun to see” a 46% increase in streaming residuals following 2020 contract negotiations.

NBCUniversal, the parent company of NBC News, is a member of the AMPTP.

Jones said she had started development on a show about Black cowgirls that she recently sold to Freeform, an ABC multiplatform channel aimed at younger viewers, but the strike interrupted that work. Her savings — and her parents — will help her “stay alive” in Los Angeles, she said, even if she has to find a new apartment with a roommate. In the meantime, she got a second job at Northwestern University as a virtual advocate for students affected by sexual violence.

The last WGA strike, which started in late 2007, lasted about three months and left dozens of shows shortened or canceled. The popular Tracee Ellis Ross-led comedy “Girlfriends,” for example, ended abruptly without a series finale in early 2008. Black social media users have speculated recently whether other shows featuring racial minorities could meet similar fates this time.

“I feel pretty confident that we’re not going to get canceled,” said Brittani Nichols, 34, a writer and comedian who said she was supposed to return to work on the ABC comedy “Abbott Elementary” the week the strike began. “But there’s a chance that there will be less ‘Abbott’ next season.”

Nichols said she worries about the viability of TV writing as a profession for marginalized writers in coming years: “If we don’t win this, it’s not going to be a job that a lot of people can have anymore.”

Franklin Leonard, the founder of the Black List, a platform that highlights unproduced pilots and screenplays, said aspiring writers are typically expected to “move to Los Angeles, get a job that keeps the lights on and network until someone pays attention to you.” Leonard, who is not a WGA member, added: “For whom is it easiest to do that?

“Because race is kind of a proxy for class in America,” Leonard continued, “inevitably, kicking those lower rungs out will have outsized effects on communities that have historically been excluded and communities who have had issues of economic oppression.”

There are signs that diversity behind the screen influences viewership. The UCLA report found that theatrical films with casts that were 31% to 40% minority generated the most revenue last year.

In streaming, movies featuring casts with the same level of diversity netted the highest median ratings among a wide range of demographics, including viewers ages 18-49, as well as white, Latinx, Asian and “other-race” households. Streaming ratings peaked for Black households on films with 41% to 50% minority casts.

Some in Hollywood said the algorithm-driven streaming era has muddied what counts as success in the industry.

Erika Alexander, an actor and producer known for her role as Maxine Shaw in the ’90s Fox sitcom “Living Single,” has found success with documentaries like “John Lewis: Good Trouble,” which is streaming on two major platforms. But she said some of her experience working with streamers has been opaque.

“They have to tell you how you’re doing, and they do not share that data,” Alexander said. Often when a series gets canceled, she said, “it wasn’t based on how well it was doing inside of the app — it was based on whether it was pulling in new subscribers.”

Alexander’s company is a WGA signatory, meaning it abides by certain terms agreed to with the union.

Some strikers said their push for more long-term parity and transparency is worth some short-term sacrifice. Jones said she has been developing a project with a major studio for two years without pay, a common industry practice.

“I can’t keep working like this for free,” she said. “I don’t want to do that anymore.”