The strange, tinkling song of Mercury's magnetic field sounding like a chime in the solar wind has been detected for the first time ever.

Known as "whistler-mode chorus waves," these bizarre chirping signals—converted to sounds—have been previously detected at Jupiter, Saturn and our home planet, as well as being remotely observed at Uranus and Neptune.

Now, Mercury joins the fray of planets experiencing these strange chorus waves. This was a surprise to scientists as Mercury does not share the same thick atmosphere and permanent radiation belt as the other planets, according to a new paper published in the journal Nature Astronomy.

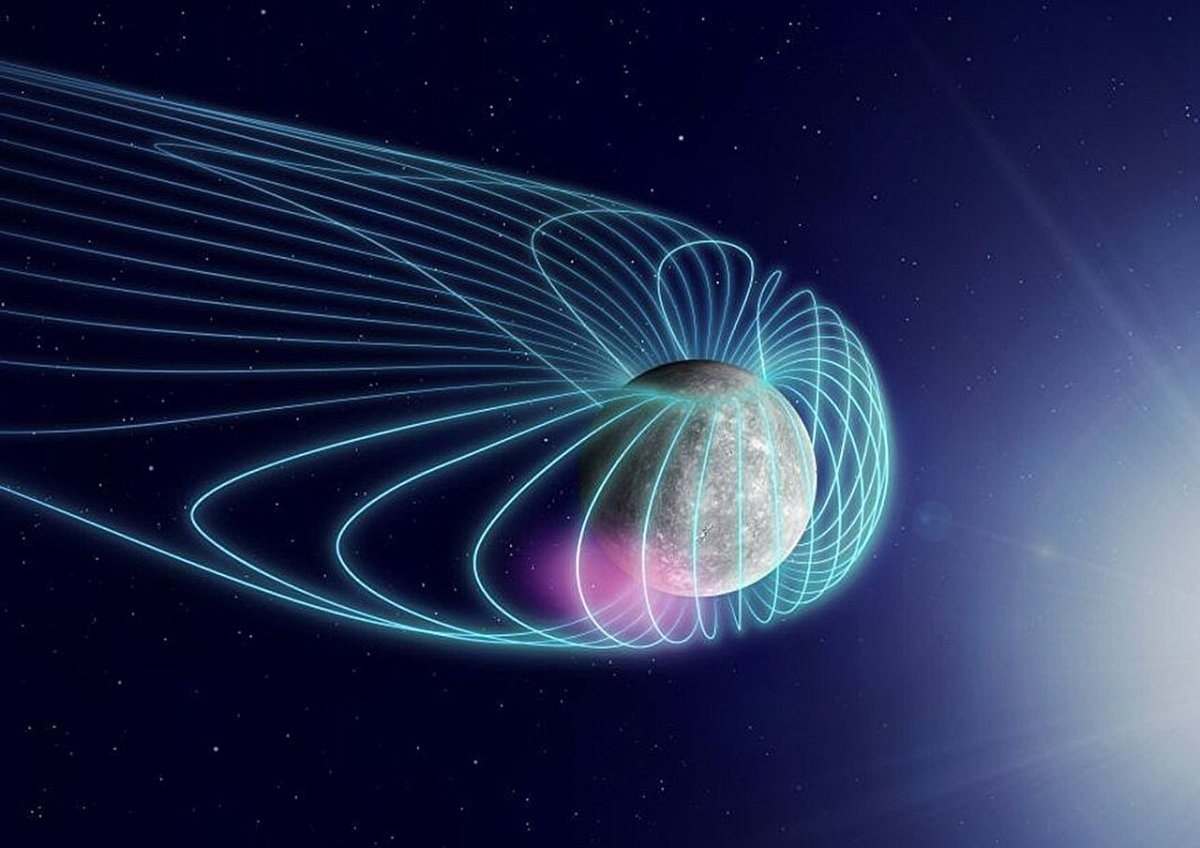

These chorus waves are triggered by energetic electrons becoming trapped in the magnetosphere of a planet, rippling along its magnetic field lines and generating plasma waves. When recorded, these waves can be converted into sounds that chime and tinkle, depending on the movement of the electrons.

"This chorus wave (electromagnetic wave) is generated by the electron cyclotron motion along the magnetic field line," Mitsunori Ozaki, an associate professor of electrical, information and communication engineering at Kanazawa University, in Japan, and co-author of the study, told Newsweek. "The electron motion is equivalent to the electric current, thus the electric current by the electron motion causes the chorus waves in the planet's magnetospheres.

"Unfortunately, the chorus wave is electromagnetic wave, so we cannot directly hear it, but the chorus wave is generated at the audio frequency band, so we can hear it by converting from the electromagnetic signals detected by electric antennas to audio signals."

The Mercury chorus waves were found to be unusual, however, as they were found in only a small chunk of Mercury's magnetosphere: the dawn sector.

"Here, we present the direct probing of chorus waves in the localized dawn sector during the first and second Mercury flybys by the BepiColombo/Mio spacecraft. Mio's search coil magnetometers detected chorus events with tens of picotesla intensities in the dawn sector, while no clear chorus activity was observed in the night sector," the authors wrote in the paper.

The authors added that this may be due to the waves either being promoted in this region, or being suppressed elsewhere. After modeling and simulating Mercury's magnetosphere, they found that it was likely that Mercury's dawn sector was the most-efficient area for the transfer of energy from electrons to the chorus waves.

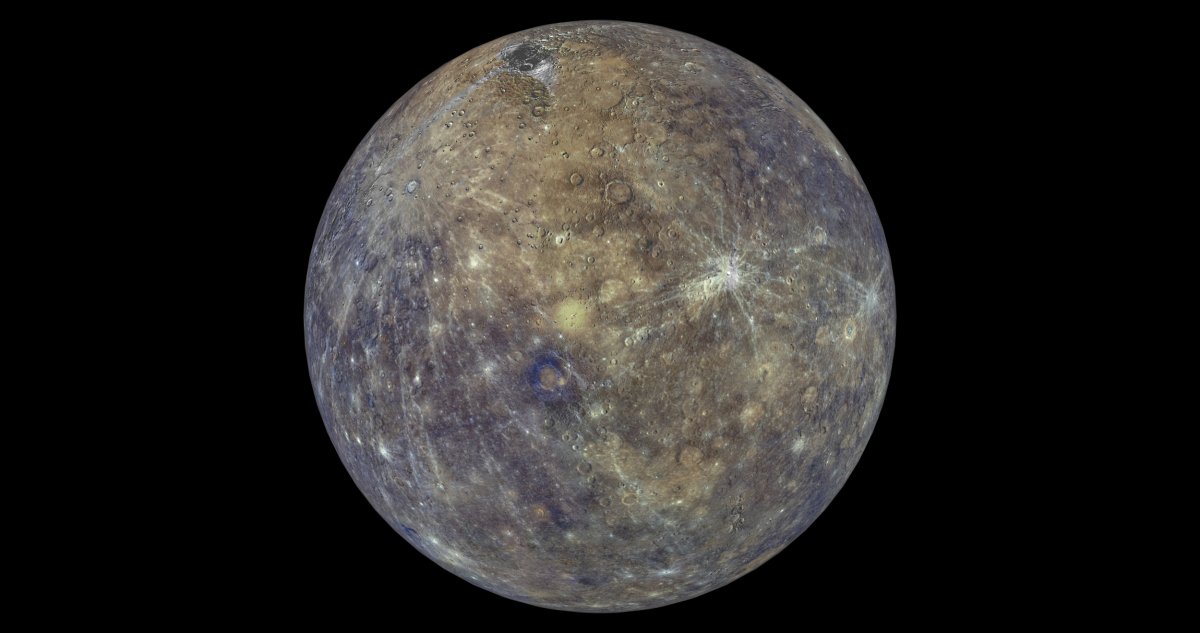

Mercury is the closest planet to our sun, orbiting at a distance of 38 million miles away, compared to Earth's 93 million-mile orbit. It completes a full orbit every 88 days, and is only around a third of the size of Earth, according to NASA.

Mercury has a very thin atmosphere of oxygen, sodium, hydrogen, helium, and potassium. This is known more specifically as an exosphere as these gases come from solar wind and meteoroids blasting atoms off the surface. Due to this thin atmosphere, Mercury's surface temperature can veer wildly between extremes, hitting 800 degrees Fahrenheit during the day and dropping to minus 290 degrees Fahrenheit at night.

Mercury also has a much-weaker magnetic field than Earth, and was discovered only by the Mariner 10 expedition in the 1970s. We still don't know much about the planet, but this discovery has led the researchers to hope that this finding can reveal more details about Mercury's magnetic field.

"Mercury has a small magnetosphere, however, the magnetic field strength is a very weak ( 1 percent in comparison with the Earth's), so the existence of chorus waves in Mercury was a long-lasting scientific issue from the Mariner 10 project in the 1970s," Ozaki said.

"Our study showed the direct evidence of Mercury's chorus waves and our direct observations of chorus waves at Mercury were a final piece of the evidence proving the universality of chorus waves in all the magnetized planets in our Solar System."

These discoveries were made by the Mio spacecraft, launched on October 20, 2018, which is on its way to orbit Mercury by December 2025. The authors also hope to use these findings to learn more about magnetic fields in general, including on Earth, and how the solar wind can impact them.

"Our study should contribute to the future development of space station in the Moon, because the Moon has a magnetic anomaly and air-less body like Mercury, which may cause to drastic change the plasma condition by chorus waves at the Lunar magnetic anomaly," Ozaki said.

"Our findings will also contribute to the general scientific audience's basic knowledge of the importance of the planet's magnetic fields, because the planet's magnetic fields act as an impenetrable barrier for high energy plasmas, which are directly affect to DNA damages in the past, present, and future."

Do you have a tip on a science story that Newsweek should be covering? Do you have a question about Mercury? Let us know via science@newsweek.com.

Update 10/20/23, 8:09 a.m. ET: This article was updated with comment from Mitsunori Ozaki.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Jess Thomson is a Newsweek Science Reporter based in London UK. Her focus is reporting on science, technology and healthcare. ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.