The moment that lingered in my mind after a recent triathlon-science conference came from a panel discussion with “gold-medal coaches,” including Iñaki Arenal, head of the Spanish high-performance team, and Malcolm Brown, coach of the Olympic-medal-winning Brownlee brothers. I asked the coaches to name the single biggest change in elite triathlon training in 2017 compared with a decade earlier. The answers had nothing to do with wearable tech or secret workouts. Instead both gave the same answer: strength training.

Of course, endurance coaches have been preaching the benefits of strength since athletes wore togas. But the practical reality of combining endurance and strength training has always been trickier than the theory, thanks in part to an apparent “interference effect” between the two workout types. To get the best of both worlds, you have to take a closer look at the molecular signals involved in strength and endurance training—and figure out how to maximize both at the same time.

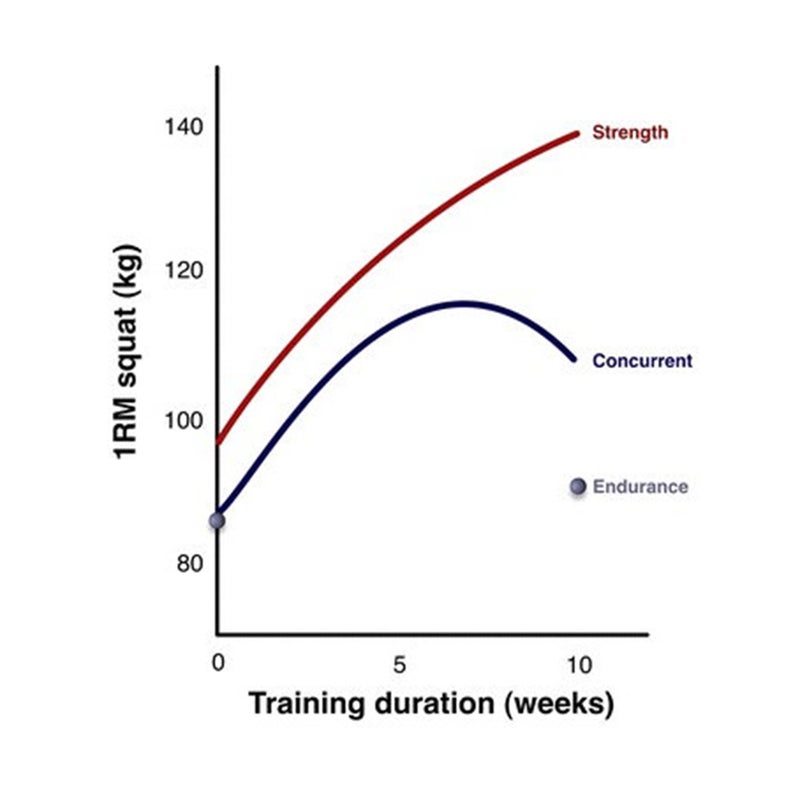

The classic study on concurrent strength and endurance training was published by Robert Hickson in 1980. After ten weeks of seriously intense endurance training, strength training, or both, the verdict was that strength training didn’t hinder endurance gains but endurance training did hinder strength gains. Here’s what the strength changes in the three groups looked like (from a graph redrawn by University of California Davis researcher Keith Baar in this paper):

Initially the concurrent group gains strength, but after a while the results start to tail off and even reverse.

It’s worth noting that a top triathlete like Alistair Brownlee isn’t necessary concerned with packing on muscle—in fact, that could be a negative. Instead, according to Brown, the roughly three hours a week Brownlee spends in the gym are mainly focused on building durability, so that he can survive the 30-plus hours he spends swimming, biking, and running. The challenge is far more acute in sports like rowing, which involve huge endurance-training volumes but also require as much muscle mass as you can muster. And from a health perspective, recreational endurance athletes like me often struggle to put on and maintain muscle while racking up miles.

Hickson’s results offered evidence that the “skinny endurance athlete” phenomenon isn’t only because endurance athletes can’t be bothered to do strength training, are too tired to do it right, or are genetically wired to have no muscle. (Though all those factors probably play some role.) Instead there seems to be some underlying conflict between strength and endurance adaptations.

One explanation of the interference effect goes something like this: Resistance training activates a protein called mTOR that (through a cascade of molecular signals) results in bigger muscles. Endurance training activates a protein called AMPK that (though a different signaling cascade) produces endurance adaptations like increased mitochondrial mass. AMPK can inhibit mTOR, so endurance training blocks muscle growth from strength training.

This has been the prevailing picture for the past decade or so, based on cell culture and rodent experiments. In humans, though, it doesn’t seem to be that simple. Instead, according to Baar, one of the leaders in applying molecular biology to study training adaptations, the key point may be more straightforward. By the halfway point of the famous Hickson study, he estimates that the strength-training group was burning 2,000 calories per week in their training while the concurrent training group was burning 6,000 calories per week.

There’s now emerging evidence of an alternate molecular-signaling pathway in which metabolic stress—not just from endurance training but also from other triggers like caloric deficit, oxidative stress, and aging—hinders muscle growth. This alternate pathway involves a complex series of links between a “tumor suppressor” protein, another protein called sestrin, and various other obscure acronyms. But details aside, what’s particularly intriguing about the hypothesis is that it’s highly sensitive to the presence of the amino acid leucine, which binds to sestrin and triggers the synthesis of new muscle protein. And this, Baar says, suggests some strategies to beat (or at least minimize) the interference effect.

The solution isn’t as simple as just eating more. Even if you successfully balance caloric intake with expenditure over the course of a day, you may still end up doing your strength workouts in a low-energy state. So you need to focus on getting back into “energy balance” before hitting the gym. If you’ve been out riding for a few hours, this will take more than an energy bar and a scoop of yogurt.

The most interesting point, in my view, is Baar’s suggestion that you should design your strength workout to use heavy weights so that you reach failure after relatively few reps. This will maximize the metabolic signals for muscle growth, while minimizing the calories burned and metabolic stress. (Lifting to failure also ensures that the last few reps are done slowly, which may decrease tendon stiffness and reduce injury risk, he points out.) He advocates lifting one set for each exercise, with loads chosen to aim for the following repetition ranges:

- Upper body, compound movements: 6–8 reps

- Upper body, isolation movements: 6–10 reps

- Lower body, isolation movements: 10–12 reps

- Lower body, compound movements: 20–25 reps

As you get stronger and hit the upper end of these ranges before hitting failure, increase the weight for the next workout.

The role of leucine suggests it’s especially important to get enough protein throughout the day, to make sure that muscle-growth signals aren’t suppressed by a leucine shortage. A pre- or postworkout shake isn’t sufficient; instead aim for about 0.25 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight, four to six times a day. For a 150-pound person, that’s a small tuna sandwich and a glass of milk. If you’re training seriously, you may need a higher protein hit—0.4 grams per kilogram—to get the same effect.

Does workout order matter? In the traditional mTOR versus AMPK picture, you’re better off doing endurance before strength training. That’s because the endurance signals only stay elevated for about an hour following exercise, while strength signals stay on for 18 to 24 hours. But in the revised picture, where metabolic stress is the key, the order of workouts is less important than your energy balance.

Finally, it’s important to point out that you shouldn’t stress about this unless you’re training pretty damn hard. As a general rule of thumb, if you’re not doing endurance training four or more times a week, or pushing your workouts (i.e., sustaining above 80 percent of VO2max), you’re unlikely to be hurting your strength gains.

Will following these tips transform scrawny endurance athletes into muscled marvels? Not overnight. But understanding what’s going on at the cellular level can help optimize our training choices, even if the immediate effects are invisible. As Baar puts it, “What we can’t see sets the parameters for what we can see.”

Discuss this post on Twitter or Facebook, sign up for the Sweat Science e-mail newsletter, and check out my forthcoming book, ENDURE: Mind, Body, and the Curiously Elastic Limits of Human Performance.