Dahui Zonggao (1089–1163) was (arguably) the most important Zen master ever. (1) He is credited with developing the keyword method (話頭, huatou) that revolutionized Zen practice and that, in my opinion, is the greatest development in the meditation realm since Shakyamuni Buddha. Most importantly, the innovative teaching of Dahui has probably led to more awakening (aka, kensho) than that of any other Zen teacher in history.

So kudos and bows to great old master Dahui!

Up until now, Dahui’s best known writings in English are Swampland Flowers: The Letters and Lectures of Zen Master Ta Hui, translated by J.C. Cleary, and The Letters of Chan Master Dahui Pujue, translated by Broughton and Watanabe. I’ve written extensively about many aspects of Dahui’s dharma and so will include an index of those essays in the footnotes for you. (2) Also, because I’ve previously written a rough biography on Dahui’s turbulent life, The Most Revered and Most Reviled Zen Master Ever, I won’t repeat that now.

The focus of this post is Dahui’s newly published, Treasury of the Eye of the True Teaching, the first posthumous translation by the late, greatly prolific Thomas Cleary. I’ll be contrasting Dahui’s Shobogenzo with the great Dogen’s Shobogenzo, going full-geek with some analysis of the Zen masters that Dahui presents in the selections in his Shobogenzo, highlighting some hinky details, speculating minimally about the meaning of the data, and giving you a few samples.

But, first, I’ve got to say what an incredibly rich text Thomas Cleary and Shambhala are serving up here! Wow. A huge array of koan, verses, and penetrating dharma talks from a very wide pull of the enormously rich Zen tradition. If you’re a Zen teacher looking for some new material, you’re going to love Dahui’s Shobogenzo. If you’re a Zen student, well, honestly, it’s probably too much, unless you’re working in the post-kensho process with koans featuring subtle distinctions. If you’re a wild-eyed, wide-ranging Zen ronin, go wild (or find a teacher and give up your identity as always being on the outside of whatever sides there are).

Dahui’s oft repeated main theme in his teaching career was about the importance of kensho. This comes through powerfully in many of these selections, but unlike his Letters that was written almost exclusively for householders working for an initial kensho, his Shobogenzo highlights many practitioners in face-to-face encounters who are doing the subtle work of post-kensho training.

The first selection in the text, for example, begins with this (only a portion of the dialogue is shared here):

Master Langya asked Master Ju, “Where have you just come from?”

Master Ju said, “From the riverlands.”

“Did you come by boat or by land?”

“By boat.”

“Where’s the boat?”

“Underfoot.”

“How do you utter an expression of not being on the road?”

Dahui then offers his comments that include this: “When one dog barks at nothing, a thousand monkeys bite in actuality. Because religious leaders do not have clear insight, they originate sectarian doctrines, confusing and misleading people of later times. What they don’t realize is that the two great masters’ (Langya and Master Ju) stimulus and response were like the sun and moon shining in the sky.” (3)

As I said above, I’ll share some more selections below.

Click here to support my Zen teaching practice of which translations and writings like this are one facet.

Distinguishing Dogen’s and Dahui’s Shobogenzo

I first heard rumors of Dahui’s Shobogenzo in the early 1980s and have been waiting eagerly to get my hands on it ever since, so am delighted that Shambhala has published it now. You might recognize the title – Dogen (1200-1253) borrowed it for his magnum opus. This is a curious thing, in my view, that has long seemed to me like a window into Dogen’s quirky mind. So a word about that before I dive into Dahui’s Shobogenzo.

Dogen, you see, was generally not a fan of Dahui, although he did praise him once for sitting zazen until a boil on his ass broke. Dogen’s issue with Dahui was probably about lineage rivalry. A direct successor of Dahui had given “dharma transmission by courier” to Dainichibo Nonin (大日房能忍, d.u.), who then founded one of the first Japanese Zen schools, the Daruma-shu, in the generation prior to Dogen. Many of Dogen’s students had come to him from monasteries associated with the Daruma-shu, so Dogen seemed keen on distinguishing what he was about from what Dahui was about. You can read more about that if you are so inclined in The Luminous Koun Ejō Zenji: Background, Awakening, Legacy.

Dahui had also been rude, really rude, to a Soto ancestor of Dogen, Zhenxie Qingliao (Japanese, Choryo Seiryo, 1089-1151), saying that he understood a koan while Qingliao did not – and this during a talk at Qingliao’s place when Dahui was Qingliao’s guest! Dogen seems to have been holding some sourness a hundred years later. Some folks will regard this as heresy, but, yup, greatly awakened masters like Dogen can be petty too. If you’re interested for more about this incident, I go into that here: Just Sit or Wake Up? A Tale of Two Old Teachers.

In addition to being occasionally petty, sometimes old Dogen did not play fair. As I’ll argue in an upcoming post, tentatively titled, “Dogen’s Worst Moment in his Shobogenzo,” Dogen seems to intentionally and with malice distort Dahui’s bio for utterly sectarian aims and gains. Not the best One School Zen look. And it appears from where I sit that his criticism of Dahui is widely misunderstood in Soto circles today. Spoiler alert: Dogen cleverly criticizes Dahui for not effectively using the keyword method and not having a definitive awakening, not for using the keyword method and emphasizing kensho. So Dogen criticizes Dahui for exactly what he was most clear about. Makes me wonder if old Dogen was joking. But I’ll save unpacking all that further for a later post.

In any case, the common story nowadays is that Dogen borrowed Dahui’s title in order to straighten things out about the subtle, true dharma. But maybe Dogen was in such awe of the old master that he wanted to imitate him. After all, Dogen borrowed Dahui’s title twice. Here’s Daido Loori Roshi’s explanation about the two Dogen Shobogenzo:

“[Dogen] is best known for his comprehensive and profound masterwork, the Kana, or Japanese, Shobogenzo. This monumental achievement, a collection of ninety-five discourses and essays composed in Japanese between the years 1231 and 1253, is a unique expression of the Buddhadharma based on Dōgen’s profound religious experience. A less-known work of Dogen’s is his Mana Shobogenzo, or Shobogenzo Sambyakusoku (Treasury of the True Dharma Eye: Three Hundred Cases), a collection of three hundred case kōans written in Chinese.” (4)

In terms of comparison, Dahui’s Shobogenzo, aka Treasury of the Eye of the True Teaching, is much more like Dogen’s Mana Shobogenzo, essentially, a list of koans without verses or commentary, than Dogen’s Kana Shobogenzo, with koans, for sure, but with long, brilliant commentary. In Dahui’s Shobogenzo, he has a comment for the first selection and then his own teisho is recorded at length in the last selection. In between, Dahui adds quirky capping phrases, usually just a single sentence, to about 20% of the selections.

Finally in terms of comparison, while Dogen stopped at 300 cases in his Maha Shobogenzo, Dahui didn’t go “Whoa!” until he’d gotten to selection #668.

Why Did Dahui Compile His Shobogenzo?

He tells us,

“While I was in exile in Hengyang, I closed my door and retired, taking no interest in external affairs. From time to time patchrobed mendicants would ask for help, so I couldn’t but answer them. The Chan men Zhongmi and Huiran took notes, which over time accumulated into a huge volume. They brought it to me and asked for a title, wishing to reveal it to later generations so that the treasury of the eye of true teaching of the Buddhas and Chan masters does not perish. So I entitled it Treasury of the Eye of True Teaching, and made the story of Langya the first chapter. Thus there is no order of precedence in the adepts featured herein, nor division of sect; I have only taken their realizations of the handle of transcendence as capable of dissolving sticking points for people and untying bonds, just so they may have accurate perception.” (5)

Dissolving 668 sticking points to be exact!

“Living in exile” refers to the fourteen year period in Dahui’s life during which he was defrocked and exiled. Prior to exile, from 1137 – 1141, from age forty-nine to fifty-three, Dahui had been the abbot of Jingshan monastery in the new capital, Lin-an. Jingshan monastery housed two-thousand monastics, and many high-ranking officials came to study with him as well. From this high post, Dahui was regarded as the leader of Buddhism in the realm. Then Dahui was accused of taking the wrong side in a political dispute, and so fell from grace, and was exiled to Hengyang and then Guangdong, both in the South, both places notoriously dangerous due to the prevalence of malaria, various other plagues, and other hostile life-ending elements.

In those days, sending someone to the South like this was the Empire’s way of getting said someone killed. But not Dahui. Students continued to come to him seeking his instruction and he continued teaching, and sometimes he offered them a koan, teisho, or verse that was then recorded by his students on average about four times a month, although officially he was “retired.”

I don’t remember seeing periods of exile in many other Zen teacher’s records (I can only think of Furong Daokai), but it isn’t a big surprise that Dahui was exiled. After all he had vowed,

“In the past, in the calm place, I made a great vow that I would rather replace all the beings subjected to the sufferings of hell with this body, than not use this mouth to express the buddhadharma because of human emotions, thus blinding everyone.” (6)

When you tell the truth, you tend to piss people off. I love that about him and am inspired by it to this day.

The Data on Dahui’s Shobogenzo

Of the 667 entries with primary teachers other than Dahui, I didn’t find the lineage or generation for about 10%. Why? Well, Dahui had access to texts that we don’t today, as well as a five-hundred year oral tradition. Also, a guy has to set some search limits – I stayed within what’s available in English, especially Ferguson’s Zen’s Chinese Heritage and various online resources. A deep dive into Whitfield’s Records of the Transmission of the Lamp might yield more hits, but Whitfield’s paper texts have indexes are not good, so that looked like it’d require more time than I thought wise to invest in this aspect.

Importantly, if you are looking for new Zen material, less than 10% of the selections in Dahui’s Shobogenzo are also found in the standard koan collections. However, that includes fourteen of the forty-eight case No Gate Barrier (Japanese, Mumonkan). (7) Also, Dahui included many of the founding stories of the great teachers of the classical period.

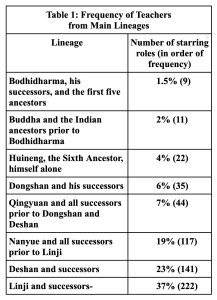

Nevertheless, the teacher selection data based on 90% of the teachers included in Dahui’s text is still quite instructive in regards to those he selected and those he didn’t. A few observations:

- Dahui selected over 250 different masters for the teaching seat (not including all the secondary roles).

- Unlike the koan collections that are now standard (see note 7), and both of Dogen’s Shobogenzo, Dahui selected teachers disproportionately from his own lineage. As Table 1 below indicates, 56% are from Nanyue and his successors and Linji his successors.

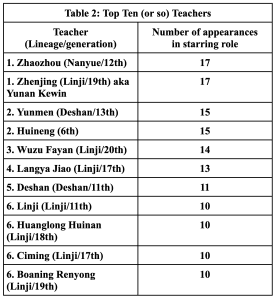

- Of those in the Linji succession, Dahui’s primary interest are those teachers in generations close to his own twenty-second generation. 169 masters (76% of the Linji masters in the text and 28% of the entire collection) are from the just four Linji generations, the seventeenth through the twentieth in China.

- Dahui’s Shobogenzo has a concentration of teachers from the Huanglong branch of Linji, although his own Yangqi branch was the other predominant Linji line. One factor in this may be how widespread the Huanglong was in the twentieth and twenty-first generations. Levering notes that “The Huanglong branch of the Linji house had been in its [nineteenth] and [twentieth] generations a large and powerful lineage. There were at least eighty-five Dharma-heirs of Huanglong Huinan 慧南 in the [nineteenth] generation, and over three hundred in the [twentieth] generation.” (8) In fact, Zhenjing (1025-1102; 19th generation; aka Yunan Kewin, one of Huanglong Huinan’s eighty-five heirs) is tied for the most selections with the great Zhaozhou, both starring in seventeen selections. See Table 2, below. It is notable that Zhenjing was the teacher for Dahui’s first Huanglong-branch Linji teacher, Letan Wenzhun (1062-1115), with whom Dahui trained for ten years. Before Letan’s death, he told Dahui that there was still something missing in his realization and so he would not give him dharma transmission. Nevertheless, Letan has seven entries in Dahui’s Shobogenzo.

- After almost twenty years of intensive Zen training, Dahui trained with Yuanwu Keqin (1063-1135) for just eight-months during which time he finally realized great awakening and became one of Yuanwu’s successors. Yuanwu, however, does not appear in Dahui’s Shobogenzo. Yuanwu’s teacher, though, Wuzu Fayan (1024-1104), appears fourteen times and is in third place.

- Dahui appears to be disproportionately disinterested in masters from the Dongshan Liangjie line that became Japanese Soto. He includes only thirty-five such masters (6% of the collection). And as for teachers in Dongshan Liangjie’s line after the sixteenth generation’s consignment transmission from Fushan to Touzi, there are none (click here for more about this). In addition, some of Dahui’s capping phrases for koans involving Soto masters seem to have a critical edge (even more critical than usual). For example, with the awakening story of Yunyan, Dongshan’s teacher, Dahui remarks, “It’s not that he didn’t get an insight, but he still didn’t get out of the cave of complications.” (9) That Soto teachers after the sixteenth generation don’t show much in Dahui’s text, and when they do, Dahui tends to be negative, should probably not be too surprising, given that Dahui was intensely critical of the silent illumination approach that was popular in a segment of Soto lineage especially in the nineteenth generation (click here for more about this). Dahui’s first Zen teacher (by my reckoning when he was nineteen and twenty years old), prior to his decade with Letan, was Dongshan Daowei, a direct successor of Furong Daokai (and probably regarded by Furong as his primary successor as the robe from Dayang was transmitted to Daowei). The young Dahui, though, had issues with Daowei’s understanding of awakening – which might be one source of his vow to unreservedly express the buddhadharma, as well as his negative view of the Soto lineage.

- Dahui had an affinity for the Deshan line (23% of the text’s teachers), which like the Dongshan line, sprang from Qingyuan, Shitou, and Yaoshan. And Deshan himself comes in a solid 5th place in terms of frequency of mention. Again see the tables below for more.

A few selections to give you a taste

First, here’s a short passage from Dahui’s final teisho:

“If you are determined to succeed to the way of this school, it is necessary for mind and environment to be as one before you have a little bit of accord. Hearing me say something like this, don’t immediately close your eyes and play dead, forcibly arranging your mind to be at one with the environment. In this, no matter how you try, how can you arrange it? Do you want to attain genuine unity of mind and environment? You just need to make a complete break and resolute cutoff, take away what forms false imagination in your skull, cut off the eighth consciousness in one sword stroke, naturally, not applying arrangement.” (10)

Second, a short passage from the master who ties with Zhaozhou for the most references, Zhenjing, cited above:

“Countless methods of teaching, all subtle meanings, the sayings of the teachers all over the world, one seal beginning to end, never dared differ. Leaving aside for the moment not differing, where is the seal? Do you see? If you see, you are not monks, not lay people; you have no partiality, no factionalism—everyone is entrusted. If you do not see, I withdraw myself.” (11)

Finally, an example of a koan with a capping phrase by Dahui:

“’Muslin Robe’ Zhao one night pointed to the half moon and asked Elder Pu, ‘Where has the other part gone?’

“Pu said, ‘Don’t misconceive.’

“Zhao said, ‘You’ve lost a piece.’

“Dahui said, ‘He gets up by himself and falls down by himself.’” (12)

(1) Dahui Zonggao (1089–1163) ;大慧宗杲; aka, Dahui Punjue; Japanese, Daie Soko).

(2) Index on Dahui posts:

- The Most Revered and Most Reviled Zen Master Ever: This post got the series rolling. It includes some of the bio on this great teacher and some of the reasons that he is most revered and most reviled. It also includes some of the reasons why Dōgen had such issues with him – not Dōgen’s best look, in my opinion. In the rest of the series, I work through nine themes in The Letters of Chan Master Dàhuì Pujue identified by translators Jeffrey L. Broughton and Elise Yoko Watanabe, as well as three lists of Dàhuì’s Don’ts, and an essential teaching on the identity center.

- You Have To Do It On Your Own: The Keyword Instruction of Dàhuì: Dàhuì, of course, says it best: “The hilt of this sword lies only in the hand of the person on duty. You can’t have someone else do it for you. You must do it yourself. If you stake your life on it, you’ll be ready to set about doing it.”

- Great Uncertainty and the Real Work: More On The Keyword Instruction of Dàhuì: “You must generate a singular sensation of uncertainty.” This post explores the importance of Great Doubt for doing keyword practice – it really can’t be overstated.

- Let Go of Making the Ground Flutter: More On The Keyword Instruction of Dàhuì: This post includes a bit about Miàodào, a nun and the student who Dàhuì was working with when he first discovered the keyword method. In terms of the themes that Broughton and Watanabe identify, this is about assuming a stance of composure.

- Clicking and Snorting Across The Flood: More On The Keyword Instruction Of Dàhuì: The main theme here is about being neither tense, nor slack. I begin with a story from the Pali Canon Buddha: “How did you, dear sir, cross the flood?” [The Exalted One:] “Without tarrying, friend, and without hurrying did I cross the flood.” “But how did you, dear sir, without tarrying, without hurrying, cross the flood?” “When I friend, tarried, then verily I sank; when I, friend, hurried, then verily I was swept away. And so, friend, untarrying, unhurrying, did I cross the flood.”

- Saving Energy is Gaining Energy: More On The Keyword Instruction Of Dàhuì: Saving on the expenditure of diligent practice energy is gaining [awakening] energy – this is one the most important keys to householder practice. Don’t just read it – do it!

- Tasteless Within The Tasty: More On The Keyword Instruction Of Dàhuì: This theme presents a shift to the focus on breakthrough. Dàhuì says, “When you notice the keyword has no logic, no taste, that your mind is ‘hot and stuffy,’ it’s the state wherein you, the person on duty, relinquishes their life.” I also add a verse with capping phrases from Wansong and his Record of Going Easy to help make the point.

- “I’m Too Dumb” And Working The Edge Of The Precipice: More On The Keyword Instruction Of Dàhuì: Whatever assessment we have of ourselves – too dumb or too smart – we have to let it go to sit at the edge and let go of that too. Dàhuì says, “Come to the edge of life-death right where the doubt block is not yet broken.” And I say, “It is a place of full aliveness. Right there is the place to let it all go.” This post also weaves in some Dōgen and Wansong, lest you think Dàhuì was a one-teacher show.

- Break Through Is A Must: More On The Keyword Instruction Of Dàhuì: The post begins with this: “Break through is a must if you want to verify the truth of this one great life and not just take others’ words for it, hiding behind the Buddha’s robes, as it were. Or hiding inside your own robes. Hiding in the bells and smells of Zen orthodoxy. Or spending a dharma career trying to talk others into believing that non-enlightenment is really enlightenment. Exhausting!” Dàhuì says, “…If you can break through this word mu 無, you’ll break through all of them at the very same time, without having to ask anyone anything.”

- Broken To Smithereens: More On The Keyword Instruction Of Dàhuì: This one really points to the work that can be done through thoroughgoing Zen training. Dàhuì says, “If you want true stillness, what’s necessary is the smashing of the mind of life-death. Even without doing diligent practice—if the mind of life-death is smashed—stillness will come of its own accord.” I also include a bit about changing the kōan curriculum to emphasize more complete embodiment in our times.

- Dàhuì’s Don’ts: Still More On The Keyword Instruction Of Dàhuì: Dàhuì is probably best known for his lists of “Don’ts” for those working with the mu kōan. He offered at least three such lists that are interrelated and clearly shifting for his audience, arising, I imagine, based on his developing insights for how best to work with students to catalyze awakening. I offer one of the lists here with brief comments.

- Dàhuì’s Second List of Don’ts for the Dog Kōan: For example, “Also, do not turn to opening your mouth in the place of accepting reality as it is.”

- Solely Engrossed In One Thing: Dàhuì’s Last List of Don’ts: Dàhuì’s purpose with this list of Don’ts is to put the earnest student of the great mystery into a corner of birth death where they cannot move an inch, and then block the student’s twitchy attempts to escape upright encounter with this very the corner, the edge of the precipice of birth death. Suddenly, the edge of the precipice collapses and the world of suffering becomes the world of illumination – the very same world outside in.

- Going Against the Identity Center and Going With: The Missing Motif: This post is one of the most important and most practical for Zen training, offering instructions on one of the keys to studying the self and forgetting the self.

(3) Thomas Cleary, Treasury of the Eye of the True Teaching, 1-2.

(4) John Daido Loori and Kazuaki Tanahashi, The True Dharma Eye: Zen Master Dogen’s Three Hundred Koans,

(5) Cleary, 3.

(6) The Letters of Chan Master Dahui Pujue, 7.1, trans. Dosho Port.

(7) The koan collections I consider standard are The No Gate Barrier, The Blue Cliff Record, The Record of Going Easy (aka, The Book of Serenity), The Record of the Transmission of Illumination (ok, that’s an exception, but it is explicitly about the Soto lineage), Entangling Vines, and The Record of Empty Hall.

(8) See Miriam Levering’s “Dahui Zonggao and Zhang Shangying: The Importance of a Scholar in the Education of a Song Chan Master,” in Journal of Song-Yuan Studies, No. 30 (2000), pp. 115-139, for more about Dahui’s relationship with the Linji Huanglong branch.

(9) Cleary, 278.

(10) Ibid., 407.

(11) Ibid., 375.

(12) Ibid., 311.